Validating Emergency Department Checklists Across Age Groups: Methodologies, Applications, and Impact on Patient Safety

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the development and validation of Emergency Department (ED) checklists tailored for distinct age populations, including pediatric, adult, and geriatric patients.

Validating Emergency Department Checklists Across Age Groups: Methodologies, Applications, and Impact on Patient Safety

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the development and validation of Emergency Department (ED) checklists tailored for distinct age populations, including pediatric, adult, and geriatric patients. It explores the foundational need for age-specific tools to address unique clinical presentations and risks, details rigorous methodological approaches for checklist creation and implementation, addresses common challenges in optimization, and examines validation strategies for assessing real-world efficacy. Aimed at researchers and clinical developers, this review synthesizes current evidence and best practices to enhance patient safety and improve outcomes in high-risk ED environments through reliable, validated checklists.

The Critical Need for Age-Specific Emergency Department Checklists

Understanding High-Risk ED Environments and the Imperative for Standardization

Emergency Departments (EDs) globally face increasing patient volumes and resource demands, creating crowded environments where accurate risk stratification becomes both critical and challenging [1]. The core problem lies in the absence of standardized operational definitions and validated assessment tools across ED settings, particularly for vulnerable populations like behavioral health patients [2]. This standardization crisis impacts every facet of emergency care—from predicting patient outcomes to benchmarking departmental performance. Without common vocabulary and metrics, ED leaders cannot effectively manage, report, or compare care across institutions, undermining data-driven leadership and ultimately patient care [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these challenges, intensifying the strain on hospital infrastructure and making clinical triage increasingly difficult [1]. Within this context, the imperative for standardization extends beyond operational efficiency to encompass the reliable validation of data collection instruments, including questionnaires, across diverse ED environments and age groups. This article examines the current state of high-risk ED environments, explores benchmarking and prediction model initiatives, and establishes why standardization is fundamental to advancing ED research and quality improvement, particularly in the validation of research tools.

The High-Risk ED Landscape: Behavioral Health and Operational Strain

The ED environment is uniquely characterized by high-acuity, high-uncertainty patient presentations, with behavioral health emergencies representing a particularly strained component of the system. The Behavioral Health Workgroup of the Fifth Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) Summit highlighted the critical need for precise definitions and metrics to manage barriers for this patient population [2]. Their consensus recommendations provide a framework for quantifying this operational burden, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Behavioral Health Operational Metrics for ED Benchmarking

| Metric | Definition | Operational Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Health Patient Rate | Proportion of overall ED patients with a primary diagnosis of mental health illness and/or substance use disorder [2]. | Quantifies the volume burden of behavioral health on the ED system. |

| Pediatric Behavioral Health Patient Rate | Proportion of pediatric ED patients (age ≤18 years) dispositioned with a primary or secondary behavioral health diagnosis [2]. | Measures the specific burden of pediatric behavioral health presentations. |

| Behavioral Health Boarding Hours per Day | Average number of daily hours that behavioral health patients board in the ED, starting from the order to admit or transfer [2]. | A critical indicator of ED and hospital capacity constraints and patient flow inefficiency. |

| Behavioral Health Consultation Rate | Number of behavioral health consultations per 100 ED visits [2]. | A marker of the clinical burden and resource intensity required for behavioral health patients. |

| Average BH Sitter Hours per Day | Average number of hours daily that ED personnel must dedicate to one-on-one monitoring of behavioral health patients [2]. | Directly translates to staffing resource allocation and associated costs. |

The EDBA Summit also emphasized innovative care models to address these challenges, including ED patient navigators and substance use navigators who coordinate care and facilitate treatment linkages, as well as mobile crisis teams and sobering centers that offer community-based alternatives to ED intake [2]. Standardizing the metrics in Table 1 allows EDs to benchmark their performance, identify areas for improvement, and objectively evaluate the impact of implementing these new models of care.

Benchmarking and Prediction Models: The Power of Standardized Data

The movement toward standardization is perhaps most advanced in the field of ED prediction models, where public benchmarks are revolutionizing research reproducibility and model comparison. As clinical triage becomes more complex, prediction models offer the potential to identify high-risk patients and prioritize resources [1]. The widespread adoption of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) has provided the data necessary to develop these models.

A pivotal development is the creation of open-source benchmark datasets, such as the one derived from the MIMIC-IV-ED database, which includes over 400,000 ED visits [1]. This benchmark suite standardizes data preprocessing and defines three key clinical prediction tasks, outlined in Table 2 below. Such benchmarks eliminate cumbersome data preprocessing, provide a fixed test set for fair model comparisons, and significantly lower the entry barrier for new researchers [1].

Table 2: Standardized Clinical Prediction Benchmarks for ED Outcomes

| Prediction Task | Definition | Clinical and Operational Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization | Inpatient care site admission immediately following an ED visit; patients transitioning to ED observation are not considered hospitalized unless subsequently admitted [1]. | Indicates resource utilization (bed allocation) and patient acuity, facilitating resource allocation planning. |

| Critical Outcome | A composite outcome defined as either inpatient mortality or transfer to an ICU within 12 hours of presentation [1]. | Identifies critically ill patients requiring urgent ED resources and early intervention to mitigate poor health outcomes. |

| 72-Hour ED Reattendance | A patient's return visit to the ED within 72 hours after being discharged from a previous ED visit [1]. | A widely used indicator of the quality of care and patient safety, potentially identifying inadequate triage or treatment during the initial visit. |

These models are evaluated against established triage systems like the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) and scoring systems such as the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) and National Early Warning Score (NEWS) [1]. The existence of a public benchmark ensures that different machine learning models and traditional scoring systems can be compared fairly, accelerating progress in ED-based predictive analytics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ED and Questionnaire Research

To conduct rigorous research in ED operations and questionnaire validation, specific "research reagents" and methodologies are essential. The table below details key tools and protocols derived from recent studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Tool or Protocol | Function & Application | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MIMIC-IV-ED Benchmark Suite [1] | Provides a standardized, preprocessed public dataset for developing and comparing ED prediction models. | Includes master dataset, data processing scripts, and defined prediction tasks (hospitalization, critical outcome, reattendance). |

| EDBA Definitions Dictionary [2] | Provides a consensus-based, standardized vocabulary for ED operations metrics. | Essential for ensuring consistent data collection and valid benchmarking across different institutions and studies. |

| Health Belief Model (HBM) Framework [3] | A theoretical framework for developing and validating questionnaires assessing knowledge, perceptions, and health behaviors. | Structures items around constructs like perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, and barriers to explain and predict behavior. |

| Cognitive Interviewing [4] | A pre-testing method for validating questionnaires by interviewing participants to understand their thought process when answering items. | Ensures questions are interpreted as intended, improving content validity and feasibility, especially in unique populations. |

| Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE) Development [4] | A method for quantitatively eliciting preferences for healthcare services or attributes. | Requires careful, culturally sensitive development involving literature review, stakeholder interviews, and attribute ranking. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Research Questionnaire

The development of a reliable and valid questionnaire is a multi-stage, methodical process. The following workflow, adapted from rigorous methodological studies, outlines the key steps for creating a tool to assess constructs like knowledge, perceptions, and avoidance behaviors in a specific population [4] [3].

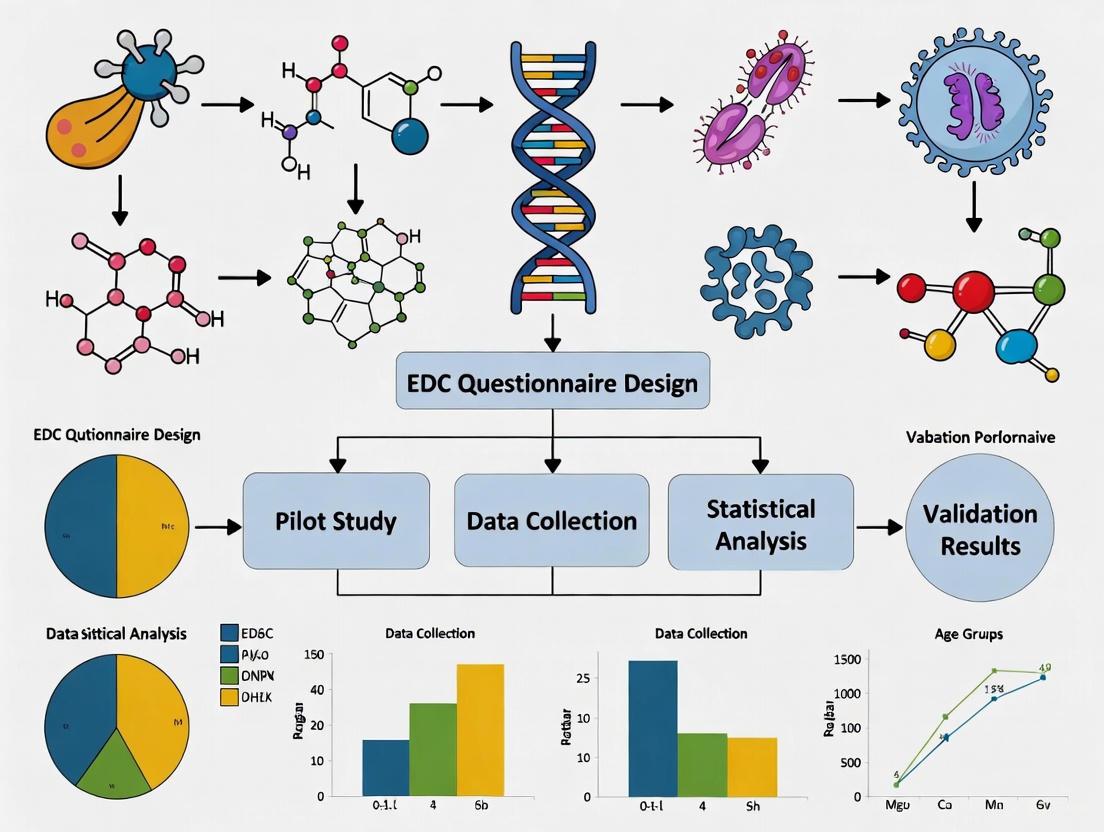

Diagram 1: Questionnaire Validation Workflow

The process begins with Phase 1: Tool Development. This involves establishing a foundation through a comprehensive literature review and selecting a guiding theoretical framework, such as the Health Belief Model [3]. Subsequently, items are generated or adapted, a process greatly enriched by conducting semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders (e.g., patients, providers) to ensure cultural and contextual relevance [4]. The final step in this phase is a preliminary pretest, using methods like cognitive interviews, to refine the wording, format, and comprehensibility of the questionnaire [4].

This is followed by Phase 2: Psychometric Testing. The refined questionnaire is administered to a larger sample in a pilot survey [3]. The collected data is then subjected to rigorous statistical analysis. Reliability is tested, typically using Cronbach's alpha to assess the internal consistency of the constructs [3]. Validity is also assessed, which may involve techniques like Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (EFA/CFA) to verify that the questionnaire's structure aligns with the intended theoretical constructs [5]. A questionnaire that meets reliability and validity standards through this process becomes a final, validated tool for research.

Visualization and Data Presentation in Scientific Communication

Effective communication of scientific findings, whether operational benchmarks or research results, relies heavily on clear data visualization. Adhering to established guidelines ensures that graphs and tables are accessible and interpretable for the target audience of researchers and professionals.

Guidelines for Effective Data Presentation

- Make Graphics Self-Explanatory: Charts should include clear titles, legends, and definitions on the same page. The "golden rule" is that if a graphic requires extensive explanation, there is a flaw in its design [6].

- Optimize Bar Charts: As the most common graphic in comparative reports, bar charts should be augmented with the actual numerical value, ordered from best to worst performance, and use a scale showing at least zero and 100 for orientation [6].

- Ensure Accessibility with Color: Color should be used thoughtfully. To accommodate color vision deficiencies, minimize the use of red/green combinations. Use a patterned bar or a lighter tone of the same color for comparators instead of a different color [6]. All elements must maintain sufficient contrast; Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) AA requires a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 for normal text [7].

- Limit Table Size: Tables should display no more than seven providers or measures at a time, as the human short-term memory struggles with larger amounts of information. For bigger datasets, information should be broken into smaller, meaningful chunks [6].

The path toward improved patient outcomes and operational excellence in high-risk ED environments is inextricably linked to the rigorous standardization of definitions, metrics, and research tools. The initiatives led by the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance to create a shared operational vocabulary [2] and the development of public benchmarks for prediction models [1] represent significant strides forward. For researchers, this means that validating data collection instruments, such as questionnaires for different age groups, must be conducted with the same methodological rigor—employing theoretical frameworks, stakeholder engagement, and robust psychometric testing [4] [3]. By embracing these standardized approaches, the emergency care community can generate comparable, high-quality data, accelerate the pace of research, and ultimately translate findings into more effective and equitable patient care.

Unique Clinical Challenges in Pediatric Emergency Assessment and Triage

Pediatric emergency assessment and triage present a distinct set of clinical challenges that differentiate this field from adult emergency care. The physiological, developmental, and psychological uniqueness of children necessitates specialized approaches for accurate triage and intervention. Unlike adults, children often cannot articulate their symptoms clearly, requiring clinicians to rely on observational skills, caregiver reports, and age-appropriate assessment tools [8]. This complexity is compounded by the high-stakes environment of emergency departments where timely identification of critically ill children is paramount for improving outcomes and reducing mortality, particularly in low-resource settings where pediatric mortality within 24 hours of hospital presentation can reach 33% [9]. The task of distinguishing stable patients from critically ill children across a spectrum of age-dependent presentations, nonspecific symptoms, and overlapping clinical findings represents a fundamental challenge for emergency care providers [8].

Comparative Analysis of Pediatric Triage Systems

Various triage systems have been developed to address the unique needs of pediatric emergency assessment. The table below provides a structured comparison of three prominent systems used globally, highlighting their key features, strengths, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Pediatric Emergency Triage Systems

| Triage System | Key Features & Methodology | Strengths | Limitations & Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency Triage, Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) | Uses clinical signs (e.g., respiratory distress, shock, severe dehydration) to identify life-threatening conditions without complex diagnostics [9]. | High sensitivity; designed for low-resource settings; linked to a 40% reduction in pediatric mortality in Malawi [9]. | Requires consistent refresher training (skills decline post-training); adherence challenges in busy settings [9]. |

| South African Triage Scale (SATS) for Pediatrics | Combines a Triage Early Warning Score (TEWS) with a list of clinical discriminators for emergency symptoms [9]. | Good sensitivity and negative predictive value; more effective than using clinical discriminators or TEWS alone [9]. | Requires basic diagnostic tools (e.g., pulse oximeters) often unavailable in very low-resource settings [9]. |

| Pediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS) | Utilizes age-specific pediatric vital signs and behavioral observations to track clinical deterioration [8] [9]. | Associated with lower mortality and fewer clinical deterioration events [9]. | Limited validation studies in low-resource settings; effectiveness depends on staff training and resource availability [9]. |

Methodological Considerations for Research and Validation

Study Design and Data Collection Protocols

Robust research in this field requires methodologies that account for pediatric-specific challenges. Cross-sectional studies and randomized controlled trials represent common approaches, with data collection often involving standardized questionnaires, clinical assessments, and biomarker analysis [10] [11]. Research focusing on pediatric populations must incorporate age-stratified recruitment to capture developmental variations, such as studies targeting specific groups from infants to adolescents [8]. For tool validation, researchers should employ rigorous psychometric testing, including assessment of internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha, to ensure reliability across different age groups [3]. Furthermore, longitudinal designs with pre- and post-intervention surveys are valuable for measuring changes in knowledge, readiness to change behaviors, and clinical outcomes following implementation of new triage protocols or educational interventions [11].

Quantitative Data Presentation and Analysis

Effective presentation of quantitative data is crucial for interpreting pediatric emergency research findings. Categorical variables, such as triage acuity levels or presence of specific symptoms, should be presented using absolute and relative frequencies in clearly formatted tables to facilitate comparison across studies [12]. For numerical variables like vital signs or laboratory values, researchers should organize data into frequency distribution tables with appropriate class intervals, typically between 6-16 categories with equal amplitudes [13]. Visual presentation through histograms, frequency polygons, or line diagrams can effectively demonstrate trends and distributions, though all graphics must be self-explanatory with clear titles, legends, and scales [12] [6] [13]. Statistical analysis should employ appropriate methods for comparing triage accuracy across systems, often using multiple logistic regression to investigate associations while controlling for confounding variables [14].

Table 2: Essential Methodological Components for Pediatric Triage Research

| Research Component | Application in Pediatric Emergency Triage | Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size Determination | Based on prevalence of target conditions and desired statistical power [3]. | Account for age stratification and subgroup analyses; collaborative multi-center studies may be needed for rare conditions. |

| Data Collection Instruments | Validated questionnaires, clinical assessment forms, laboratory test results [3]. | Adapt tools for different developmental stages; use age-appropriate pain scales and assessment protocols. |

| Outcome Measures | Triage accuracy, time to treatment, mortality, hospital admission rates [9] [15]. | Include both clinical outcomes and process measures; track mistriage rates (over- and under-triage) [15]. |

| Statistical Methods | Multiple logistic regression, mixture analysis (WQS, Qgcomp, BKMR), structural equation modeling [14] [10]. | Adjust for clustering effects in multi-site studies; use bootstrapping for indirect effects testing [10]. |

Technological Innovations and Research Tools

Emerging technologies are transforming pediatric emergency triage with artificial intelligence and machine learning models demonstrating promising sensitivity and specificity in triage prediction and septic shock recognition [8]. Point-of-care testing and ultrasound have shown significant value in accelerating diagnosis and reducing emergency department length of stay [8]. Digital tools, including mobile health applications, enable real-time measurement of biosignals and environmental risk factors, creating opportunities for personalized risk assessment [10]. For research applications, the following tools and reagents facilitate comprehensive investigation into pediatric emergency assessment.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Pediatric Emergency Assessment Studies

| Research Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Use in Pediatric Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Point-of-Care Testing (POCT) Platforms | Rapid diagnostic testing for biomarkers (CRP, blood gases, glucose, lactate) [8] [9]. | Reduces turnaround time; enables quick decision-making for febrile infants and children with undifferentiated illness [8]. |

| Biomarker Panels | Analysis of inflammatory markers (e.g., SII), uric acid, and other clinical biomarkers [14] [11]. | Identifies mediators between exposures and outcomes; tracks intervention effectiveness [14]. |

| Wearable Biosensors | Continuous monitoring of vital signs (heart rate, electrocardiogram, oxygen saturation) [10]. | Provides real-time physiological data for triage algorithms; enables pre-hospital assessment. |

| Environmental Exposure Assays | Biomonitoring of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (BPA, phthalates, parabens) in urine [14] [11]. | Investigates environmental contributors to respiratory and other emergency conditions [14]. |

| AI-Based Triage Algorithms | Machine learning models for risk stratification and prediction of clinical deterioration [8] [9]. | Enhances triage accuracy; identifies subtle patterns in vital signs and symptoms [8]. |

Integration with EDC Questionnaire Validation Across Age Groups

The validation of endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) questionnaires across different age groups shares important methodological parallels with pediatric triage assessment tool development. Both fields require age-appropriate validation strategies that account for developmental differences in symptom reporting, comprehension, and behavioral patterns [3]. Research has demonstrated that EDC exposure assessments must consider age-specific exposure pathways and metabolic differences, similar to how pediatric triage must accommodate age-dependent variations in normal vital signs and symptom presentation [8] [11].

The connection between EDC exposure and respiratory conditions highlights another intersection between these fields. Studies using NHANES data have revealed that certain EDCs, including bisphenol A and most phthalates, show positive correlations with preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm), a precursor to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [14]. This relationship underscores the importance of environmental exposure assessment in comprehensive pediatric emergency evaluation, particularly for children presenting with respiratory symptoms.

Diagram 1: Pediatric Triage with EDC Considerations. This workflow integrates age-specific assessment with potential environmental exposure evaluation, highlighting parallel validation needs across development stages.

Pediatric emergency assessment and triage present unique challenges that demand specialized approaches, tools, and research methodologies. The comparison of triage systems reveals that context-appropriate implementation is crucial, with systems like ETAT showing significant mortality reduction in low-resource settings while facing sustainability challenges. The methodological considerations outlined provide researchers with frameworks for developing and validating assessment tools that account for developmental variations across pediatric age groups. The integration of technological innovations, including artificial intelligence and point-of-care testing, offers promising avenues for enhancing triage accuracy and efficiency. Furthermore, the parallel validation needs between pediatric triage tools and EDC questionnaires across age groups suggest opportunities for methodological cross-fertilization. Future research should focus on adapting these systems for specific healthcare contexts while maintaining rigorous validation standards to ensure optimal emergency care for pediatric populations across the developmental spectrum.

Emergency Departments (EDs) globally are experiencing a surge in visits from older adults, a population with unique and complex medical needs [16]. Geriatric syndromes—including frailty, polypharmacy, and atypical disease presentations—represent a significant challenge for ED clinicians, as these conditions are frequently interrelated and can dramatically impact patient outcomes [17] [18]. The presence of these syndromes often complicates diagnosis and treatment, requiring specialized approaches that differ from standard ED protocols designed for younger, healthier populations [16]. Understanding the prevalence, interrelationships, and clinical implications of these syndromes is crucial for improving emergency care for older adults, guiding the development of targeted assessments, and informing future research, including the validation of diagnostic tools like the Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical (EDC) questionnaire across diverse age groups [19].

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on geriatric syndromes in the emergency department setting, providing a clear comparison of their prevalence and impact.

Table 1: Prevalence and Impact of Key Geriatric Syndromes in the ED

| Geriatric Syndrome | Reported Prevalence | Key Associated Factors/Outcomes | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical Presentation | 28.6% (181/633 cases) [20] | Most common presentation: absence of fever in diseases known to cause fever (34.42%). Independent risk factors: complicated UTI (OR 4.66) and dementia (OR 3.48) [20]. | Retrospective audit of ED patients ≥65 years [20] |

| Frailty | 70.2% of patients in a Mexican study [18]; 43.5% classified as frail (CFS 5-9) in a multicenter study [21] | Independent predictor of hospital admission (OR 1.414), ICU admission (OR 1.254), and in-hospital mortality (OR 1.434) [21]. | Prospective cohort study [18]; Multicenter retrospective study [21] |

| Polypharmacy | Prevalence of 59% in frail older adults [17] | Associated with adverse drug events, falls, hospitalizations, and mortality. Increases the risk of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) [17]. | Umbrella review [17] |

| Co-existing Geriatric Syndromes | Average of 4.65 (±2.76) syndromes per individual [18] | Cognitive impairment (adjusted OR 6.88) and dependence (adjusted OR 7.52) were independent predictors of in-hospital mortality [18]. | Prospective study of OAs admitted to the ED [18] |

Experimental Protocols and Assessment Methodologies

To ensure consistency and reliability in research and clinical practice, standardized protocols are used to identify and assess geriatric syndromes. The following section details the key methodologies cited in the literature.

Protocol for Assessing Atypical Presentations

A retrospective medical record audit is a common method for investigating atypical presentations [20].

- Study Population: Patients aged ≥65 years who visited the ED. A typical sample size can be over 600 patients, selected randomly from annual visits [20].

- Data Collection: Demographic data and clinical information are collected from patient records. The operational definition of an "atypical presentation" must be explicitly stated, for example: "the absence of typical signs and symptoms usually associated with a final medical diagnosis," such as lack of fever in a disease known to cause fever, lack of pain, or presentation as a geriatric syndrome (e.g., functional decline, delirium) [20].

- Data Analysis: Descriptive statistics calculate the prevalence of atypical presentations. Regression analysis is then used to identify variables independently associated with these presentations, such as specific infections or cognitive impairments [20].

Protocol for Frailty Assessment Using the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)

The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is a validated, rapid tool for assessing frailty in the ED [21].

- Tool Description: The CFS is a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill). Scores of 5-9 indicate varying degrees of frailty [21].

- Implementation: Clinicians assign a CFS score based on a comprehensive clinical assessment of the patient's fitness, comorbidity, and functional status. This can be done at triage or during the initial evaluation [21].

- Outcome Correlation: The CFS score is used for risk stratification. Studies correlate CFS scores with primary outcomes such as hospital admission, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and in-hospital mortality. Its predictive performance is often compared to other scores like qSOFA, NEWS2, and REMS using logistic regression analysis and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) curves [21].

Protocol for Evaluating Polypharmacy and Deprescribing

The process of evaluating medication regimens for polypharmacy and deprescribing opportunities involves structured criteria and, increasingly, technological assistance.

- Definition and Identification: Polypharmacy is typically defined as the use of five or more medications. A patient's active medication list is reviewed to identify polypharmacy [17] [22].

- Application of Explicit Criteria: Screening tools are applied to the medication list to identify Potentially Inappropriate Medications (PIMs). Common tools include:

- Novel Approaches: Large Language Models (LLMs) for Deprescribing: A recent study utilized a two-step LLM (GPT-4o) pipeline [22]:

- Filtering: The LLM first filters a full list of deprescribing criteria (e.g., Beers, STOPP) based solely on the patient's medication list.

- Contextual Application: The LLM then applies the filtered criteria using both structured (e.g., demographics, lab values) and unstructured (e.g., clinical notes) patient data from the Electronic Health Record (EHR) to generate a deprescribing recommendation [22].

- Validation: LLM recommendations are validated against recommendations made by trained medical students, with discrepancies adjudicated by board-certified physicians [22].

Visualizing the Interrelationships: The Geriatric Triangle

The concepts of frailty, multimorbidity (multiple chronic conditions), and polypharmacy are deeply interconnected, forming a bidirectional relationship that can be conceptualized as the "geriatric triangle" [17]. The following diagram illustrates these complex interactions.

Visualizing Research and Clinical Workflows

Implementing research protocols and clinical assessments for geriatric syndromes requires structured workflows. The diagram below outlines a generalizable research workflow for validating assessment tools, such as a questionnaire, in a specific population.

The following table details essential materials and tools used in the experimental protocols featured in this field, providing researchers with a starting point for methodology development.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Geriatric Syndrome Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) [21] | Clinical Assessment Tool | A rapid, validated scale to categorize an older adult's level of frailty. | Predicting hospital admission, ICU admission, and in-hospital mortality in ED patients [21]. |

| Beers Criteria & STOPP Criteria [22] | Explicit Pharmacological Criteria | Standardized lists to identify Potentially Inappropriate Medications (PIMs) in older adults. | Screening medication lists for deprescribing opportunities in polypharmacy research [22]. |

| Large Language Models (e.g., GPT-4o) [22] | Computational Tool | To automate the filtering and application of complex deprescribing criteria using structured and unstructured EHR data. | Identifying potential deprescribing opportunities in retrospective cohort studies [22]. |

| Structured Data Collection Instruments (e.g., SIS, PHQ-9, CAM) [18] | Battery of Standardized Questionnaires & Tests | To perform a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) covering cognition, mood, function, and other geriatric syndromes. | Determining the prevalence and co-occurrence of multiple geriatric syndromes in a study population [18]. |

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) Data [22] | Data Source | Provides real-world, longitudinal patient data including demographics, diagnoses, medications, lab results, and clinical notes. | Retrospective analysis of patient outcomes and as an input source for LLM-driven deprescribing algorithms [22]. |

The evidence overwhelmingly confirms that geriatric syndromes like frailty, polypharmacy, and atypical presentations are highly prevalent, interconnected, and strong predictors of adverse outcomes in older ED patients [20] [18] [21]. Addressing these challenges requires a shift from traditional, disease-centered ED models to more holistic, patient-centered approaches [16]. This includes the routine implementation of validated assessments like the Clinical Frailty Scale and Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, as recommended by the Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines 2.0 [16] [18]. Furthermore, emerging tools like LLMs show promise in managing complexity, such as assisting with deprescribing, though they require further refinement and integration into clinical workflows [22]. Future research must continue to develop and validate robust tools—including questionnaires for various risk factors—tailored to the unique physiological and pharmacological profiles of an aging global population.

The Impact of Age-Specific Checklists on Error Reduction and Patient Safety Metrics

A detailed comparison of specialized tools enhancing safety across the patient age spectrum.

Checklists are a cornerstone of patient safety, but their effectiveness is significantly enhanced when tailored to the specific needs of different age groups. This guide compares the objectives, methodologies, and impacts of age-specific checklists against general patient safety checklists, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a data-driven analysis of their performance in reducing errors and improving safety metrics.

Comparative Analysis of Checklist Types

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and documented outcomes of general versus age-specific checklists based on current research and validation studies.

| Feature | General Patient Safety Checklists | Age-Specific Checklists (Pediatric ADLs) | Age-Specific Checklists (Infarction Code) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Reduce medical errors and enhance safety through standardized processes [23]. | Measure age-related performance in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) to establish normative references [24]. | Standardize and systematize care for time-dependent conditions (e.g., AMI) in primary care [25]. |

| Target Population | Broad, hospital-wide patients [23]. | Normal developing children (NDC) under 18 years, stratified by age [24]. | Patients presenting with suspected acute myocardial infarction, typically adults [25]. |

| Key Metrics | Medication errors, surgical complications, adverse events [23]. | Level of independence in 14 domains (e.g., dressing, eating, mobility) across 30 latent variables [24]. | Adherence to gold-standard guidelines, electrocardiogram-to-PCI time, relationship with patient safety indicators [25]. |

| Development Sample Size | Not Specified (Literature Review) [23]. | 3,079 children (1,478 females, 1,601 males), median age 10.7 years [24]. | 615 responses to online checklist [25]. |

| Validation Method | Narrative review of studies from 2013-2023 [23]. | Cross-sectional survey; factor analysis to identify latent variables; creation of age-based reference charts [24]. | Prospective validation using clinical scenarios; assessment of internal consistency and temporal robustness [25]. |

| Reported Impact | Positive impact on reducing errors; success depends on organizational culture and resources [23]. | Provides the first comprehensive reference charts for ADL performance in an Italian pediatric population [24]. | (Protocol Stage) Aims to demonstrate that checklist use increases patient safety and standardizes care [25]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Developing Pediatric Age-Specific Checklists

The creation of the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) checklist for children exemplifies a rigorous, data-driven methodology [24].

- Item Identification and Selection: Researchers identified 268 relevant items covering a wide range of daily life activities. A correlation analysis integrated with clinical judgment was used to refine this set, resulting in a final 154-item pool [24].

- Survey Administration: A cross-sectional survey was conducted using the finalized questionnaire. Data was collected from 3,079 normal developing children under 18 years of age [24].

- Factor Analysis: Exploratory factor analysis was employed to identify latent variables, which allowed researchers to group the 154 selected items into 14 domains and 30 specific skill-related areas [24].

- Modeling and Reference Chart Creation: For each latent variable, a model was developed to represent the progression of ADL performance as a function of the child's age. This process generated the age-related reference charts that serve as a normative standard [24].

Protocol for Validating a Clinical Checklist

The validation of the infarction code care checklist demonstrates how to test a tool's reliability and robustness in a clinical context [25].

- Scenario Development: Two clinical scenarios of varying difficulty were defined, with correct answers established according to gold-standard clinical guidelines [25].

- Training and Initial Response: Following annual training on the infarction code, healthcare professionals completed the online checklist for the first time based on the clinical scenarios [25].

- Temporal Robustness Assessment: The same checklist was sent to participants a second time at 30, 45, and 90-day intervals. This design assesses the checklist's internal reliability and temporal robustness by comparing the number of correct responses against the gold standard over time [25].

- Correlation with Safety Indicators: The results from the checklist responses are evaluated against other available patient safety indicators in the region, such as indicators for pharmaceutical prescription quality and care quality [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and methodologies essential for research in checklist development and validation.

| Item/Tool | Function in Research | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Factor Analysis | Identifies underlying, unobservable constructs (latent variables) that explain patterns in observed data. | Grouping 154 specific questions into 14 core domains of pediatric Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) [24]. |

| Cross-Sectional Survey Design | Collects data from a population at a single point in time to identify prevalence and relationships. | Establishing normative reference data for ADL performance across different age groups in a pediatric population [24]. |

| Clinical Scenarios (Gold Standard) | Provides a controlled, benchmarked method to test the accuracy and adherence of a checklist against established protocols. | Validating the infarction code checklist by measuring how well professional responses align with guideline-based correct answers [25]. |

| Internal Consistency (Cronbach's Alpha) | A psychometric measure that assesses the reliability of a questionnaire by determining how closely related a set of items are as a group. | Demonstrating strong reliability across all constructs (knowledge, risk perceptions, beliefs, avoidance behavior) in a tool measuring attitudes toward endocrine-disrupting chemicals [3]. |

| Health Belief Model (HBM) | A theoretical framework for understanding health-related behaviors; guides questionnaire design by structuring items around perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, and barriers. | Developing a reliable tool to assess women's perceptions and avoidance behaviors regarding endocrine-disrupting chemicals in products [3]. |

Research Workflow: From Development to Validation

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for developing and validating a checklist, integrating methodologies from the cited studies.

Key Insights for Research and Development

The evidence demonstrates that while general checklists provide a foundational safety net [23], their utility is maximized when specialized. The development of the pediatric ADL checklist highlights the necessity of large, normative datasets and statistical modeling to create age-stratified tools that can accurately identify developmental delays or impairments [24]. Furthermore, the protocol for the infarction code checklist underscores that validation requires more than expert consensus; it demands rigorous testing for internal consistency and temporal robustness to ensure reliability in high-stakes clinical environments [25]. For researchers validating tools like EDC questionnaires across age groups, these methodologies are directly applicable. Employing a theoretical framework (e.g., the Health Belief Model [3]), establishing internal consistency, and creating age-specific reference curves are critical steps for generating valid, impactful research instruments.

Building and Implementing Robust Age-Specific ED Checklists

The validation of Electronic Data Capture (EDC) questionnaires for clinical research represents a critical methodological challenge, particularly when these instruments must be adapted for different age groups. A systematic development framework is essential to ensure that resulting data are reliable, comparable, and scientifically valid. This guide objectively compares two predominant methodological frameworks used in this process: the Delphi consensus technique, which systematizes expert opinion, and patient-centered feedback approaches, such as Discrete Choice Experiments (DCEs), which directly incorporate patient preferences and lived experience [26] [4]. The integration of these frameworks is especially crucial for EDC systems, which must not only capture clinical data efficiently but also integrate seamlessly with Electronic Health Records (EHRs) to streamline research processes and reduce site burden [27]. This article provides a comparative analysis of these frameworks, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in validating EDC questionnaires across diverse populations.

Framework Comparison: Delphi Consensus vs. Patient Feedback

The selection of a development framework significantly influences the structure, content, and ultimate validity of a research instrument. The table below provides a high-level comparison of the two primary approaches.

Table 1: High-Level Comparison of Development Frameworks

| Aspect | Delphi Consensus Technique | Patient-Centered Feedback (e.g., DCE) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Purpose | To gain consensus among experts on complex issues characterized by uncertainty [26] [28]. | To elicit and understand patient preferences and priorities for healthcare services or instruments [4]. |

| Primary Input | Collective intelligence and judgment of a panel of selected experts [26] [29]. | Lived experience, values, and choice behaviors of patients or end-users [4]. |

| Typical Output | A set of consensus-based guidelines, criteria, or a structured instrument [30]. | A ranked set of attributes defining patient priorities, informing a tailored instrument or service design [4]. |

| Key Strength | Reduces bias from dominant individuals and systematizes expert knowledge [29]. | Ensures content and face validity from the end-user perspective, crucial for adoption [4]. |

| Context of Use | Ideal for problems where objective data is lacking and expert judgment is paramount [26]. | Essential for designing services or tools that must align with cultural, social, or personal user needs [4]. |

The Delphi Consensus Technique

The Delphi technique is a structured communication process that aims to achieve convergence of opinion on a specific topic through multiple rounds of anonymous, controlled feedback [26] [29].

- Process and Workflow: A classic Delphi study follows a defined iterative cycle. It begins with the facilitator distributing an initial, often open-ended questionnaire. After each round, the facilitator provides a controlled feedback report summarizing the group's responses, often with statistical aggregation and anonymous comments, prompting experts to refine their judgments [30] [29]. This process continues for a pre-defined number of rounds or until a pre-specified consensus level is reached [26].

- Key Experimental Parameters: The practical application of the Delphi method involves several critical design choices. A recent scoping review of 287 health science Delphi studies found that 81% defined consensus as a percentage agreement, though the specific threshold (e.g., 70%, 75%, 80%) varies [30]. Panel sizes are typically in the double-digits, often between 10 to 100 members, balancing diversity with manageability [26]. The same review noted that about a quarter of studies included affected parties like patients in the expert panel, and 43% of studies reported using a modified Delphi approach [30].

Patient-Centered Feedback Frameworks

Patient-centered frameworks, such as Discrete Choice Experiments (DCEs), provide a quantitative method to elicit preferences by presenting participants with a series of choices between hypothetical scenarios with varying attributes [4].

- Process and Workflow: The development of a DCE is a multi-stage, mixed-methods process. It starts with qualitative identification of the key attributes and levels that define a service or product, often through literature reviews and stakeholder interviews. These attributes are then refined through quantitative exercises like ranking surveys with the target population. Finally, the draft DCE questionnaire is validated through cognitive interviews to ensure it is understood as intended [4].

- Application in Closed Communities: This approach is particularly valuable for research involving unique populations. A 2025 study on developing a DCE for ultra-Orthodox Jewish women regarding video consultations demonstrated the necessity of deep cultural adaptation. The study engaged multiple stakeholders (women, men, rabbis, healthcare providers), used community-matched interviewers, and obtained religious leadership approval. A key finding was the community's requirement for a dedicated device, closed to the open internet, for communication with healthcare providers—a critical attribute that would be unlikely to emerge in a standard expert-driven Delphi panel [4].

Experimental Protocols for EDC Questionnaire Validation

Validating an EDC questionnaire for use across different age groups requires a hybrid approach that integrates both expert consensus and patient feedback. The following protocols provide a roadmap for this process.

Protocol 1: Modified Delphi for Item Generation and Prioritization

This protocol is adapted for creating age-appropriate item banks for EDC systems [26] [30].

- Formulate the Problem and Assemble Steering Group: Define the specific construct (e.g., medication adherence, pain intensity) and target age groups. Assemble a steering group of 5-7 experts to oversee the process.

- Panel Selection: Recruit a heterogeneous panel of 15-30 experts. For pediatric EDC validation, this should include clinical researchers, methodologists, and healthcare providers from relevant disciplines, as well as patient advocates or caregivers who can speak to the experiences of the age group [30].

- Round 1 - Idea Generation: Distribute an initial survey based on a literature review, asking panelists to suggest items or constructs relevant to the target domain and age group. Use open-ended questions.

- Analysis and Round 2 - Rating: The steering group synthesizes responses into a list of items. In Round 2, panelists rate each item on predefined criteria (e.g., relevance, clarity, age-appropriateness) using a Likert scale (e.g., 1-9). Data to collect: mean score, percentage agreement for each item.

- Round 3 - Feedback and Re-rating: Provide controlled feedback, showing each panelist their previous rating alongside the group's statistical summary. Panelists are given the opportunity to revise their ratings. Consensus can be defined a priori as >70% of panelists rating the item within the 7-9 range [30].

- Final Analysis: The steering group finalizes the item bank based on the consensus ratings and qualitative comments.

Protocol 2: Integrated Patient Feedback and Cognitive Testing

This protocol tests the face validity and comprehensibility of the Delphi-generated items with the target age groups [4] [5].

- Attribute and Level Identification (if DCE is used): Conduct semi-structured interviews or focus groups with individuals from the target age groups to understand the key attributes of the construct from their perspective. For example, for a "user-friendly EDC app," attributes for teens might include "ease of use," "privacy," and "fun design."

- Questionnaire Drafting: Incorporate the findings into the draft EDC questionnaire.

- Cognitive Interviewing: Recruit 10-15 participants from each key age group. A trained interviewer administers the draft questionnaire and uses "think-aloud" techniques and targeted probes to understand the participant's thought process. Key questions: "What does this question mean to you?" "Can you repeat that in your own words?" "How did you arrive at that answer?"

- Data Analysis and Iteration: Analyze interview transcripts for recurring issues like misinterpretation of terms, confusing response options, or sensitive topics. Revise the questionnaire iteratively until no new critical issues emerge. A study on digital maturity, for instance, used a pretest with 20 participants to assess content validity and item difficulty before finalizing its survey [5].

Data Integration and Workflow: From Framework to Validated EDC

The ultimate goal of applying these frameworks is to produce a validated EDC instrument that can be efficiently integrated into clinical research workflows. The logical relationship between the different methodological components and the final outcome can be visualized as an iterative, multi-stage process.

Diagram 1: Integrated EDC Questionnaire Development Workflow

Quantitative Data from Integration Pilots

The integration of EDC with EHR systems is a key step in reducing redundancy and improving data quality. A pilot evaluation study, the "Munich Pilot," provided quantitative data on the impact of an integrated EHR-EDC solution compared to a traditional paper-based process [27].

Table 2: Process Efficiency Gains from Integrated EHR-EDC Solution (Munich Pilot Data)

| Metric | Traditional Paper-Based Process | Integrated EHR-EDC Process | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time per Chemotherapy Visit | 14.8 minutes | 4.7 minutes | -68% |

| Time per Screening Visit | 31.6 minutes | 14.2 minutes | -55% |

| Data Entry Process Steps | 13 steps | 5 steps | -62% |

| Automated eCRF Data Population | 0% | 48% - 69% (depending on visit type) | +48% to +69% |

| Source: Adapted from "EHR and EDC Integration in Reality" evaluation study [27] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key methodological components and their functions in the systematic development and validation of EDC questionnaires.

Table 3: Essential Components for EDC Questionnaire Validation Research

| Item | Function in Research Process |

|---|---|

| Expert Panel | Provides specialized knowledge and clinical judgment to generate and prioritize items, ensuring scientific rigor and relevance [26] [29]. |

| Structured Interview/Focus Group Guide | Facilitates the systematic collection of qualitative data from patients or end-users to identify key concepts, attributes, and appropriate language [4]. |

| Online Survey Platform (e.g., LimeSurvey) | Administers Delphi rounds or patient surveys, enabling anonymous participation, efficient data collection, and complex branching logic [5] [29]. |

| Consensus Definition Criteria | Pre-specified, objective metrics (e.g., percent agreement, interquartile range) used to determine when consensus is achieved, ensuring transparency and reproducibility [26] [30]. |

| Cognitive Interview Protocol | A structured guide for "think-aloud" interviews and probing questions to assess patient comprehension, retrieval process, and judgment formation when answering the draft questionnaire [4]. |

| EDC-EHR Integration Engine | Technical infrastructure that maps and transfers relevant clinical data from electronic health record systems directly to the EDC, reducing manual entry and transcription errors [27]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., R, SPSS) | Used to analyze quantitative data from Delphi rounds (central tendency, dispersion) and patient surveys (factor analysis, reliability testing) to support validation [5]. |

The validation of EDC questionnaires for diverse age groups is not a choice between expert consensus and patient feedback but requires their strategic integration. The Delphi technique provides a structured, defensible method for distilling expert opinion into a coherent instrument, while patient-centered frameworks like DCEs and cognitive interviewing ensure the tool is relevant, comprehensible, and respectful of the end-user's context and capabilities. Quantitative data from integration pilots demonstrate that bridging the gap between research tools like EDCs and clinical care systems like EHRs yields significant efficiency gains and data quality improvements [27]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting these systematic frameworks is paramount for generating reliable, generalizable evidence across all age groups in clinical research.

Emergency Departments (EDs) represent high-stakes environments where diagnostic errors can lead to severe patient harm. Within the broader research on validating questionnaires for Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) across different age groups, understanding and improving clinical decision-making processes is paramount. The development of a general ED safety checklist, focused on diagnostic, reassessment, and disposition phases, is a critical intervention to mitigate diagnostic error. This guide objectively compares the core components of such checklists, analyzes their efficacy based on experimental data, and details the methodologies required for their validation and implementation, providing a framework that can inspire robust methodological approaches in EDC questionnaire research.

Comparative Analysis of Checklist Components and Efficacy

A systematic review of 25 unique clinical diagnostic checklists, characterized using the human factors framework Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) 2.0, provides a basis for comparing core components and their associated impact on reducing diagnostic errors [31].

Table 1: Characterization and Efficacy of Diagnostic Checklist Components by SEIPS 2.0 Framework

| SEIPS 2.0 Component | Subcomponent | Description & Examples | Number of Checklists | Association with Error Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work System | Tasks | Checklists prompting specific actions (e.g., "obtain a repeat history," "order a specific test") [31]. | 13 | 5 out of 7 checklists demonstrating error reduction addressed this subcomponent [31]. |

| Persons | Elements addressing clinician or patient factors (e.g., knowledge, demeanor, health status) [31]. | 2 | Efficacy not prominently reported [31]. | |

| Internal Environment | Factors related to the immediate care setting (e.g., workspace design, noise) [31]. | 3 | Efficacy not prominently reported [31]. | |

| Processes | Cognitive | Elements targeting clinical reasoning (e.g., "list differential diagnoses," "consider cognitive biases") [31]. | 20 | 4 out of 10 checklists demonstrated improvement [31]. |

| Social & Behavioural | Components advocating communication with team members or patients [31]. | 2 | Efficacy not prominently reported [31]. | |

| Outcomes | Professional | Addressing outcomes like clinician burnout or fatigue [31]. | 2 | Efficacy not prominently reported [31]. |

The data indicates that checklists oriented toward the Tasks subcomponent are more frequently associated with a reduction in diagnostic errors compared to those focusing primarily on Cognitive processes [31]. This suggests that checklists prompting concrete actions are a high-yield component for improving diagnostic safety.

Experimental Protocols for Checklist Development and Validation

The development and validation of a reliable tool, whether a clinical checklist or a research questionnaire, require a rigorous methodological approach. The following protocols, drawn from checklist research and EDC questionnaire validation studies, provide a template for robust scientific development.

Systematic Review and Human Factors Analysis

The foundational protocol for evaluating existing checklists involves a systematic review and characterization using a structured framework.

- Objective: To identify, characterize, and evaluate the efficacy of checklists aimed at reducing diagnostic error [31].

- Search Strategy: A medical librarian performs serial literature searches across multiple databases (e.g., PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science) using controlled vocabulary and keywords related to "checklist," "differential diagnosis," and "diagnostic errors" with no restrictions on publication date or language [31].

- Study Selection: Articles are included if they contain one or more checklists aimed at improving the diagnostic process. Screening and eligibility determination are performed independently by two authors [31].

- Data Extraction & Synthesis: A standardized template is used to extract data on study design, population, and checklist content. Each unique checklist is independently characterized according to the SEIPS 2.0 framework [31].

- Quality Assessment: The risk of bias in individual studies is evaluated using standardized tools such as Cochrane's RoB 2.0 for randomized studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies [31].

Tool Development and Psychometric Validation

This protocol outlines the process for creating a new assessment tool and establishing its reliability and validity, a process directly applicable to both ED safety checklists and EDC exposure questionnaires.

- Objective: To develop a self-administered questionnaire and verify its reliability and validity for measuring specific health behaviors [19].

- Initial Item Generation: An initial item pool is developed through a comprehensive review of existing literature and questionnaires. For a reproductive health behavior questionnaire, this resulted in 52 initial items [19].

- Content Validity Verification: A panel of experts (e.g., clinical specialists, subject matter experts, language experts) assesses the content validity of each item. The Item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVI) is calculated, and items failing to meet a predetermined threshold (e.g., above 0.80) are removed or revised [19].

- Pilot Study: A pilot test is conducted with a small sample from the target population to identify unclear items, assess response time, and refine the questionnaire layout [19].

- Psychometric Testing:

- Sample Size: Recruitment of a sample size sufficient for stable factor analysis, often aiming for 5-10 participants per item or a minimum of several hundred participants [19].

- Reliability: Internal consistency is tested using Cronbach's alpha, with a minimum threshold of 0.70 for new tools and 0.80 for established ones [3] [19].

- Validity:

- Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): Conducted to uncover the underlying factor structure. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett's test of sphericity confirm data adequacy. Factors are selected based on eigenvalues greater than 1 and a scree plot [19].

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA): Performed to verify the model derived from the EFA. Model fit is assessed using absolute fit indices like χ2, SRMR, and RMSEA [19].

Implementation and Workflow Integration

For an ED safety checklist to be effective, its implementation must be carefully designed.

- Integration into Clinical Workflow: The checklist must be embedded into the existing electronic health record (EHR) or clinical workflow to ensure it is used at the point of care without causing significant disruption [31].

- Structured Guide for Critical Decisions: An example is the consensus guide for caring for adult patients with suicide risk, which includes a discharge planning checklist to assist ED professionals in making safe discharge decisions and setting up follow-up care [32].

Diagram 1: Tool Development and Validation Workflow. This diagram outlines the key phases and steps involved in the systematic development, validation, and implementation of a reliable checklist or questionnaire.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are essential for executing the experimental protocols described above, particularly for the development and validation of EDC questionnaires, which share methodological principles with clinical checklist research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Tool Development and Validation

| Item Name | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Health Belief Model (HBM) | A theoretical framework for guiding questionnaire design; structures items to assess perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy [3]. | Serves as the conceptual foundation for a questionnaire on women's perceptions and avoidance of EDCs in personal care products [3]. |

| Content Validity Index (CVI) | A quantitative metric for evaluating how well individual items (I-CVI) and the entire scale (S-CVI) represent the defined construct, as rated by a panel of subject matter experts [19]. | Used to refine a 52-item pool for a reproductive health behavior survey, removing items failing to meet the 0.80 validity threshold [19]. |

| Cronbach's Alpha (α) | A statistical measure of internal consistency reliability, indicating the extent to which all items in a tool measure the same underlying construct [3] [19]. | Used to demonstrate strong reliability (α ≥ 0.80) across constructs (knowledge, risk perceptions, beliefs, avoidance) in a questionnaire about EDCs [3]. |

| Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) | A statistical method used to identify the underlying relationships between measured variables and to group items into distinct factors or constructs [19]. | Applied to survey responses from 288 participants to derive the final four-factor structure (e.g., health behaviors through food, skin) for a 19-item questionnaire [19]. |

| Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) | A hypothesis-testing statistical technique used to confirm the pre-specified factor structure identified by EFA, assessing the model's goodness-of-fit to the data [19]. | Used to verify the structural validity of the four-factor model for reproductive health behaviors, using fit indices like SRMR and RMSEA [19]. |

| Structured Clinical Guide with Checklist | A consensus-based clinical tool that incorporates checklists to standardize decision-making for specific high-risk presentations in the ED [32]. | Provides a decision support tool and discharge planning checklist for emergency departments caring for adult patients at risk for suicide [32]. |

Diagram 2: Core Components for Tool Validation. This diagram visualizes the logical relationship between the core components, processes, and key metrics involved in validating a robust research tool.

The core components of a general ED safety checklist are most effective when they are action-oriented, integrated into clinical workflow, and developed through a rigorous, multi-stage validation process. The empirical finding that Task-oriented checklists more effectively reduce errors than those focused solely on Cognitive processes provides a critical insight for future checklist design [31]. The experimental protocols for systematic review and psychometric validation, supported by a toolkit of key research reagents, offer a robust scientific methodology. This comprehensive approach to improving diagnostic safety through structured checklists provides a powerful exemplar for researchers engaged in the complex task of developing and validating reliable assessment tools, such as those required for EDC questionnaire validation across diverse age populations.

This guide objectively compares the performance of the Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT) with other triage tools, presenting supporting experimental data within the broader context of validation science, a methodology directly applicable to EDC questionnaire research.

The Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT) is a rapid, equipment-free assessment tool used to identify critically ill or injured children. Its core function is to generate a quick, accurate general impression by visually and audibly assessing three key components: Appearance, Work of Breathing, and Circulation to the skin [33]. This 30-60 second assessment is designed for use in both prehospital and hospital emergency settings [33] [34].

Established triage systems like the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), Emergency Severity Index (ESI), and Manchester Triage System (MTS) show "moderate to good" validity for identifying high and low-urgency patients, though their performance is "highly variable" [35]. The PAT is often integrated as the foundational "general impression" step in other scales, such as the Paediatric Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (PaedCTAS) [33].

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT)

| Study Context | Sensitivity (Range) | Specificity (Range) | Key Predictive Findings | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Emergency Triage [33] | 77.4% - 97.3% | 22.9% - 99.15% | N/A | Scoping review of multiple studies (1999-2022). |

| Prehospital EMS Assessment [36] | N/A | N/A | PAT score ≥1 associated with 67.9x odds of ALS transport. PAT score ≥2 associated with 4.9x odds of ICU admission/surgery. | Retrospective cohort (n=2,929). |

| Predicting Hospitalization [34] | N/A | N/A | Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) of 0.966. | Single-center retrospective analysis (n=799). |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A critical step in tool validation is understanding the experimental designs that generate performance data. The following workflows outline common methodologies for evaluating triage tools like the PAT and for validating research instruments like EDC questionnaires, highlighting their parallel structures.

Diagram 1: PAT Clinical Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Questionnaire Validation Workflow

Key Clinical Validation Protocol

A 2025 retrospective study by Zhu et al. provides a clear protocol for PAT validation [34]:

- Population & Setting: 799 pediatric patients (0-18 years) at a single pediatric emergency department (PED).

- Tool Administration: A trained triage nurse performed the PAT assessment upon patient arrival. Nurses required at least 6 months of uninterrupted PED experience and formal PAT training.

- Outcome Measures: The primary outcome was the identification of critical cases (levels 1 & 2). PAT findings were correlated with specific outcomes including patient disposition (hospital admission), waiting time, and medical expenses.

- Data Analysis: The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve (AUROC) was calculated to determine the PAT's accuracy in predicting hospitalization. An AUROC of 0.966 indicates excellent predictive ability [34].

Connecting to EDC Questionnaire Validation

The methodology for validating a clinical tool like the PAT shares core principles with validating a research questionnaire, such as one measuring knowledge and avoidance of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) [3]. Both processes require rigorous testing of reliability and validity.

- Tool Development: The PAT was developed based on clinical pathophysiology, whereas an EDC questionnaire would be developed through a literature review and structured by a theoretical framework like the Health Belief Model (HBM) to define constructs (knowledge, risk perceptions, behaviors) [3].

- Reliability Testing: In PAT studies, inter-rater reliability is key. For questionnaires, internal consistency is measured using statistics like Cronbach's alpha to ensure all items within a construct (e.g., "risk perception") reliably measure the same idea [3].

- Pilot Testing: PAT training is piloted with healthcare workers, parallel to piloting a questionnaire on a target sample (e.g., n=200 women for an EDC survey) to refine items and ensure clarity [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential "research reagents" – the core components and methodologies – required for experiments in pediatric triage tool validation and related fields like EDC questionnaire development.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Triage and Questionnaire Validation Research

| Item/Solution | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trained Triage Nurse | Executes the tool (PAT) consistently according to protocol. | A nurse with >6 months PED experience and formal PAT training performs patient assessments [34]. |

| Standardized Data Abstraction Form | Ensures consistent, unbiased collection of outcome data from electronic health records (EHR). | Used to extract PAT scores, EMS/ED interventions, and final disposition for analysis [36]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., SPSS, Python) | Performs statistical tests to calculate reliability, validity, and predictive value. | Used to compute sensitivity/specificity, AUROC, odds ratios, and Cronbach's alpha [34] [3]. |

| Validated Reference Standard | Serves as a proxy for "true" patient urgency or chemical exposure against which the new tool is measured. | Hospital admission/ICU transfer used as a proxy for true patient acuity [36] [34]. Urinary biomonitoring for EDCs validates exposure scores [37]. |

| Theoretical Framework (e.g., HBM) | Provides the conceptual structure for developing questionnaire items and interpreting results. | The Health Belief Model guides the creation of items measuring knowledge, risk perceptions, and behaviors regarding EDCs [3]. |

| Internal Consistency Metric (Cronbach's α) | Quantifies the reliability of a multi-item scale by measuring how closely related the items are as a group. | A Cronbach's alpha >0.7 indicates strong reliability for questionnaire constructs like "knowledge" or "avoidance behavior" [3]. |

The Geriatrics 5Ms framework is a person-centered model for providing comprehensive care to older adults. Originally developed by geriatricians in 2017, this framework offers a concise yet holistic approach that addresses the core domains of geriatric care: Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity, and What Matters Most [38]. The 5Ms align with the Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative (which utilizes similar 4Ms, substituting Mentation for Mind and excluding Multicomplexity) and provide a structured methodology for clinicians to address the complex, multimorbid conditions common among older adult populations [38]. The framework supports a holistic, evidence-based approach to the medical, functional, and psychosocial complexities of aging, making it particularly valuable in clinical practice and research settings focused on older adults [39].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the 5Ms framework offers a standardized structure for evaluating interventions in aging populations. Its systematic approach ensures that critical geriatric domains are consistently assessed, enabling more meaningful comparisons across studies and populations. The integration of this framework into Electronic Data Capture (EDC) systems can significantly enhance the quality and relevance of data collected in clinical trials involving older adults, ensuring that outcomes measured align with the core priorities of geriatric care [39] [38].

The 5Ms Framework: Core Components and Clinical Applications

Detailed Framework Components

The five components of the 5Ms framework represent interconnected domains essential to geriatric assessment:

Mind: This domain encompasses the assessment and management of dementia, depression, and delirium. In clinical practice, this involves screening for cognitive impairment using validated tools, evaluating mood disorders, identifying delirium triggers, and implementing appropriate management strategies [39] [40]. The Mind domain recognizes that cognitive and mental health significantly influences treatment adherence, self-care capacity, and overall quality of life in older adults.

Mobility: This component focuses on preserving physical function and independence while reducing fall risk. Assessment includes evaluating intrinsic risk factors (such as orthostatic hypotension, balance issues) and extrinsic risk factors (unsafe home environments), identifying rehabilitation needs, and recommending adaptive equipment or assistance [39] [41]. Maintaining mobility is crucial for functional independence and directly impacts an older adult's ability to perform activities of daily living.

Medications: This domain emphasizes medication optimization, appropriate prescribing, and deprescribing of potentially inappropriate medications, particularly in the context of polypharmacy [39] [38]. It involves reviewing medication regimens for safety, evaluating for prescribing cascades, assessing adherence barriers, and aligning medications with overall goals of care, especially through deprescribing when appropriate.

Multicomplexity: This component addresses the reality that older adults often present with multiple chronic conditions, atypical disease presentations, frailty, complex biopsychosocial situations, and end-of-life considerations [39] [40]. It requires clinicians to navigate interacting comorbidities, consider prognosis in the context of frailty, and manage complex social circumstances that impact health outcomes.

Matters Most: This foundational domain focuses on identifying and incorporating the patient's personal goals, values, and preferences into care planning [39] [38]. This includes establishing goals of care, determining treatment priorities, addressing safety concerns (such as driving or living alone), and ensuring care aligns with what is most meaningful to the patient, including end-of-life preferences.

Interrelationship of the 5Ms

The 5Ms framework emphasizes the interconnectedness of its domains, where each component influences and is influenced by the others [38]. For example, medications prescribed for chronic conditions (Multicomplexity) may cause orthostatic hypotension, increasing fall risk (Mobility) and potentially leading to injury that further compromises independence (Matters Most). Similarly, cognitive impairment (Mind) can affect medication adherence (Medications) and the ability to manage multiple chronic conditions (Multicomplexity). This interconnectedness necessitates a holistic approach to assessment and intervention rather than addressing each domain in isolation.

The following diagram illustrates the dynamic relationships between the 5Ms components, with "Matters Most" appropriately positioned as the central, guiding principle:

Validation of the 5Ms Framework in Clinical and Educational Settings

Experimental Evidence for Framework Efficacy

Recent research has demonstrated the validity and feasibility of implementing the 5Ms framework across various healthcare settings. A 2023 study developed a case-based assessment using the geriatric 5Ms framework to evaluate internal medicine residents' geriatric medical expertise [39]. The assessment was aligned with undergraduate medical objectives and North American internal medicine milestones, providing a structured approach to assessing competency in geriatric care.

In this study, 68 first- to third-year internal medicine residents were randomly assigned to complete assessment and management plans for three of six geriatric cases within one hour during a mandatory academic session [39]. Two blinded educators rated performances on 5Ms dimensions and non-geriatric medical expertise using a 3-level rating scale. The results from 201 total cases demonstrated that all cases successfully integrated all 5Ms dimensions, with scores across these dimensions ranging from 0.8 to 1.3 (on a 0-2 scale), indicating partial assessment and management capabilities [39].

Critically, the study found that all 5Ms dimensions (mean=1.1, SD=0.3) scored significantly lower than non-geriatric medical expertise (mean=1.5; SD=0.3; t(64)=9.58; P<.001), highlighting specific gaps in geriatric-focused care competencies despite overall medical proficiency [39]. The assessment demonstrated moderate to strong interrater reliability (ICC=0.67-0.85, P<.001) and high face validity, with most residents rating the cases (88%) and the assessment itself (84%) as representative of clinical practice [39].

Quantitative Outcomes from 5Ms Implementation

Table 1: Experimental Outcomes of 5Ms Framework Implementation

| Study Focus | Population | Key Outcomes | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|