PER, CRY, BMAL, and CLOCK: Decoding the Molecular Clockwork for Therapeutic Innovation

This article synthesizes current knowledge on the core mammalian circadian clock genes—PER, CRY, BMAL, and CLOCK.

PER, CRY, BMAL, and CLOCK: Decoding the Molecular Clockwork for Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article synthesizes current knowledge on the core mammalian circadian clock genes—PER, CRY, BMAL, and CLOCK. It explores the foundational transcriptional-translational feedback loops that generate 24-hour rhythms and examines the intricate protein-protein interactions and post-translational modifications that ensure precision. The scope extends to methodological advances for monitoring and manipulating clock function, the pathological consequences and troubleshooting of circadian disruption, and the validation of clock components as drug targets. Finally, it discusses the translational application of this knowledge in developing chronotherapies and small-molecule modulators for diseases like insomnia, cancer, and inflammatory disorders, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Core Clockwork: Unraveling the Transcriptional Feedback Loops and Protein Complexes

Architecture of the Core Transcriptional-Translational Feedback Loop (TTFL)

Molecular Mechanism of the Core TTFL

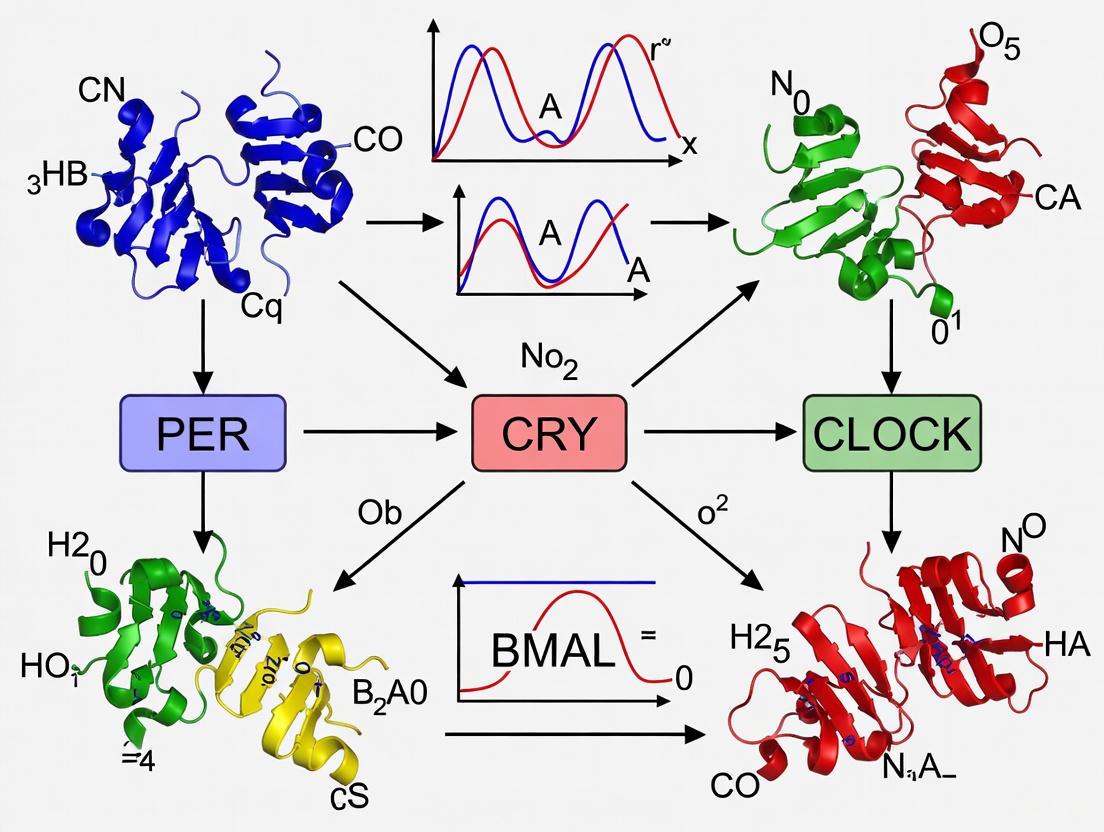

The mammalian circadian clock is an endogenous timekeeping system that generates ~24-hour rhythms in physiological processes and behavior. This rhythm is produced at a cellular level by a core Transcriptional-Translational Feedback Loop (TTFL) composed of a set of core clock genes and their protein products [1] [2] [3].

The core TTFL operates through a precisely timed cycle of gene transcription, protein translation, and negative feedback. The key components are:

- Activators: CLOCK (or its paralog NPAS2) and BMAL1 form the heterodimeric transcriptional activator complex [1] [3].

- Repressors: PERIOD (PER1, PER2, PER3) and CRYPTOCHROME (CRY1, CRY2) proteins constitute the repressor arm of the loop [1] [2].

- Post-translational Regulators: Casein kinases CK1δ/ε and the FBXL3/FBXL21 ubiquitin ligase complexes regulate protein stability [2] [3].

The CLOCK-BMAL1 heterodimer binds to E-box enhancer elements (CACGTG) in the promoter regions of target genes, including Per and Cry genes. This binding initiates the transcription of these repressor genes. After translation in the cytoplasm, PER and CRY proteins form multimetric complexes that translocate back into the nucleus to directly inhibit CLOCK-BMAL1 transcriptional activity. This constitutes the critical negative feedback that closes the loop [1] [2] [3].

The stability and nuclear translocation of the repressor complex are regulated by phosphorylation events. CK1δ/ε phosphorylate PER proteins, while AMPK phosphorylates CRY proteins. These phosphorylation events trigger polyubiquitination by SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes (β-TrCP for PER; FBXL3 for CRY), targeting them for proteasomal degradation. As PER and CRY proteins are degraded, the repression of CLOCK-BMAL1 is relieved, allowing a new cycle of transcription to begin [2] [3].

Auxiliary Feedback Loops and System Architecture

The core TTFL is stabilized and reinforced by auxiliary feedback loops that provide additional layers of regulation [2] [3].

The REV-ERB/ROR Loop

The CLOCK-BMAL1 complex also activates the transcription of nuclear receptor genes Rev-erbα/β. The REV-ERB proteins compete with ROR proteins (RORα, RORβ, RORγ) for binding to ROR-responsive elements (RREs) in the Bmal1 promoter. REV-ERBs act as transcriptional repressors, while RORs act as activators. This creates a stabilizing feedback loop that generates antiphase oscillations in Bmal1 transcription [2] [3] [4].

The D-Box Loop

A third regulatory loop involves D-box enhancer elements, which are bound by the transcriptional activator DBP (D-site albumin-binding protein) and the repressor NFIL3 (E4BP4). Both Dbp and Nfil3 expression are regulated by the core clock machinery, creating another interlocked oscillator that contributes to the overall robustness of the circadian system [2].

The hierarchical organization of the mammalian circadian system features a master pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, which synchronizes peripheral clocks in virtually all tissues and organs throughout the body. The SCN receives light input directly from the retina via the retinohypothalamic tract, allowing it to entrain to the external light-dark cycle. It then coordinates peripheral oscillators through neural, endocrine, and behavioral signals [1] [2] [3].

Quantitative Analysis of Circadian Complexes

Advanced biochemical studies have characterized the precise composition and physical properties of the core circadian complexes, providing insights into the molecular architecture of the TTFL.

Table 1: Physical Properties of Core Circadian Complexes [5]

| Complex Name | Molecular Weight | Sedimentation Coefficient (S) | Stokes Radius (nm) | Core Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLOCK-BMAL1 Activator | 255 kDa | 7.9S | 7.7 nm | CLOCK, BMAL1 |

| PER-CRY-CK1δ Repressor | 707 kDa | 15.6S | 10.79 nm | PER1/2/3, CRY1/2, CK1δ |

Table 2: Regulatory Roles of Core Clock Components

| Component | Role in TTFL | Regulation | Mutant Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLOCK | Transcriptional activator; heterodimerizes with BMAL1 | Phosphorylation modulates activity [6] | Reduces amplitude but maintains rhythm [7] |

| BMAL1 | Essential transcriptional activator partner | Transcriptional (RRE), post-translational degradation [4] | Complete arrhythmia [8] [7] |

| PER1/2 | Core repressors; facilitate CRY nuclear translocation | CK1δ/ε phosphorylation, FBXL3 ubiquitination [2] [3] | Arrhythmia or period shortening in double mutants [7] |

| CRY1/2 | Direct transcriptional repressors; block CLOCK-BMAL1 transactivation | AMPK phosphorylation, FBXL3 ubiquitination [2] [3] | Short period and eventual arrhythmia in double mutants [7] |

Research using glycerol gradient centrifugation and gel filtration chromatography of mouse liver extracts has confirmed that the circadian system operates through discrete protein complexes rather than a single large "clockosome." The CLOCK-BMAL1 activator complex and the PER-CRY-CK1δ repressor complex exist as separate entities that interact during the repression phase of the cycle [5].

Two distinct biochemical mechanisms for transcriptional repression have been identified:

- Blocking-type repression: CRY alone binds to the CLOCK-BMAL1 activation complex and directly represses its transcriptional activity.

- Dissociation-type repression: The PER-CK1δ complex, in a CRY-dependent manner, promotes the removal of CLOCK-BMAL1 from E-box elements [5].

Interestingly, PER and CRY proteins exhibit a complex relationship in regulating CLOCK phosphorylation. While CRY impairs BMAL1-dependent CLOCK phosphorylation, PER1 and PER2 (but not PER3) protect this phosphorylation against CRY-mediated effects. This functional difference may explain the phenotypic variations observed in mice lacking different Per genes [6].

Advanced Research Methodologies

Biochemical Characterization of Circadian Complexes

The quantitative data on circadian complexes presented in Table 1 was obtained through sophisticated biochemical approaches [5]:

Glycerol Gradient Centrifugation Protocol:

- Prepare nuclear extracts from mouse livers harvested at precise circadian time points (e.g., ZT0, ZT6, ZT12, ZT16, ZT19)

- Mix extracts with protein molecular weight markers

- Subject to glycerol gradient centrifugation (typically 10-40% gradients)

- Fractionate gradients and analyze fractions by Western blotting for specific circadian proteins

- Determine sedimentation coefficients by comparison with standards

Gel Filtration Chromatography Protocol:

- Prepare nuclear extracts from circadian-time-matched samples

- Pre-calibrate sizing column with standard proteins of known Stokes radii

- Apply samples to column and collect fractions

- Analyze fractions by Western blotting for circadian proteins

- Calculate molecular weights using both sedimentation coefficients and Stokes radii

Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Perform immunoprecipitation using antibodies against core clock proteins (e.g., anti-PER2, anti-CRY1)

- Wash complexes thoroughly to remove non-specific interactions

- Digest bound proteins with trypsin

- Analyze peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Identify specific complex components and potential novel interactors

Genetic and Molecular Biology Approaches

Circadian Reporter Assays:

- PER2::LUCIFERASE knock-in mice: Generate mice with luciferase cDNA knocked into the Per2 locus, enabling real-time monitoring of circadian rhythms in explanted tissues using photomultiplier tubes [6].

- Real-time monitoring in cells: Transfert NIH3T3 cells with circadian reporter constructs (e.g., Bmal1-dLuc) and monitor bioluminescence rhythms in living cells using luminometry [4].

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing:

- Generate mutant cell lines and mice with specific disruptions in regulatory elements (e.g., ΔRRE mutants with deleted RRE elements in the Bmal1 promoter) [4].

- Create targeted mutations in core clock genes to study structure-function relationships [7].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Circadian Biology Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features/Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | NIH3T3 fibroblasts [6] [4] | In vitro circadian rhythm studies | Contain functional cell-autonomous circadian clock; responsive to serum shock synchronization |

| Animal Models | PER2::LUC knock-in mice [6] [4] | Ex vivo tissue rhythm monitoring | Real-time bioluminescence recording from explanted tissues (SCN, liver, etc.) |

| Bmal1-ΔRRE mutant mice [4] | Study of auxiliary feedback loops | Disrupted RRE-mediated Bmal1 transcription while maintaining core clock function | |

| Molecular Tools | Bmal1-dLuc reporter [4] | Circadian transcriptional activity | Monitor Bmal1 promoter activity in real-time; assesses RRE function |

| pcDNA3-clock protein expression vectors [6] | Overexpression studies | Epitope-tagged (c-Myc, HA) clock proteins for transfection experiments | |

| Biochemical Reagents | Anti-PER2 antibodies [5] [6] | Immunoprecipitation, Western blot | Specific detection of PER2 protein in complex analyses |

| Anti-CRY1 antibodies [5] | Complex characterization | Immunoprecipitation of CRY1-containing complexes for proteomics | |

| Proteasome inhibitors (MG132) [3] | Protein degradation studies | Block ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to study clock protein stability | |

| Kinase Modulators | Casein kinase inhibitors (PF-670462) [6] | Post-translational regulation studies | Selective CKIε/δ inhibitor; alters PER phosphorylation and stability |

| Erbstatin analog [6] | CLOCK phosphorylation studies | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor that attenuates BMAL1-dependent CLOCK phosphorylation |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The intricate architecture of the core TTFL presents numerous potential targets for pharmacological intervention in circadian-related disorders. Recent advances include:

BMAL1-Targeted Therapeutics: The development of CCM (Core Circadian Modulator), a small molecule that binds to the PAS-B domain of BMAL1, represents a breakthrough in directly targeting core clock components. CCM binding induces conformational changes in BMAL1, altering its function as a transcription factor and modulating circadian and immune pathways [8].

Chronotherapeutic Applications: Understanding the circadian regulation of DNA repair pathways has significant implications for cancer chronotherapy. Studies using clock gene mutant mice (Cry1/2, Per1/2, and Bmal1 mutants) have revealed that the circadian clock differentially regulates nucleotide excision repair on the transcribed and non-transcribed strands of cycling genes. These findings provide a mechanistic basis for optimizing timing of platinum-based chemotherapy to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity [7].

The architectural robustness of the circadian TTFL, with its interlocked feedback loops and multiple regulatory layers, ensures precise 24-hour timekeeping while maintaining flexibility to adapt to changing environmental conditions. This sophisticated molecular framework continues to reveal new insights into the fundamental mechanisms of circadian biology and their applications in human health and disease.

The mammalian circadian clock is driven by an autoregulatory transcriptional feedback loop that operates with approximately 24-hour periodicity. At the core of this molecular oscillator is the CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimeric complex, a transcription factor that initiates the circadian transcriptional cascade by binding to specific DNA sequences known as E-box elements [9] [3]. This heterodimer belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix PER-ARNT-SIM (bHLH-PAS) family of transcription factors and serves as the primary positive regulator within the circadian clock mechanism [9]. The structural basis of CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimerization and its transcriptional activation function represents a fundamental aspect of circadian biology with broad implications for physiology, disease, and therapeutic development. This technical guide examines the atomic-level details of CLOCK:BMAL1 structure, its DNA binding mechanisms, and the experimental approaches used to characterize this essential transcriptional activator complex.

Structural Architecture of the CLOCK:BMAL1 Heterodimer

The crystal structure of the mouse CLOCK:BMAL1 bHLH-PAS domains (PDB ID: 4F3L) was determined at 2.3 Å resolution, revealing an unusual asymmetric heterodimer with extensive domain intertwining [9] [10] [11]. Each subunit contains three distinct domains: an N-terminal bHLH domain followed by two tandem PAS domains (PAS-A and PAS-B). These domains are tightly intertwined and participate in dimerization interactions, resulting in three distinct protein interfaces between the corresponding domains of CLOCK and BMAL1 [9].

The spatial arrangement of these domains differs strikingly between the two subunits. In BMAL1, the second helix of the bHLH domain (α2) is nearly continuous with the N-terminal flanking helix (A′α) of the PAS-A domain, despite a ~15 residue flexible loop (L1) insertion. In contrast, CLOCK exhibits a substantial ~23Å displacement between the end of α2 and the beginning of the PAS-A A′α helix, bringing the CLOCK PAS-A domain into direct contact with the α2 helix of its own bHLH domain [9].

Structural Asymmetry and Electrostatic Properties

The CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer displays significant structural and electrostatic asymmetry. The BMAL1 subunit has an overall positive electrostatic potential with a theoretical pI of 9.01, while the CLOCK subunit exhibits a negative electrostatic potential with a pI of 5.86 [9]. This charge distribution creates a dichotomy in potential interaction surfaces, with exposed CLOCK PAS domains displaying largely negative electrostatic potential, while exposed BMAL1 PAS domains are mostly positively charged or neutral. This electrostatic asymmetry likely contributes to differential interactions with regulatory proteins such as PER1, PER2, CRY1, and CRY2 [9].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of CLOCK:BMAL1 Domains

| Domain | Structural Features | Interface Characteristics | Conserved Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| bHLH | Basic region mediates DNA contact; helix-loop-helix mediates dimerization | Direct interaction between CLOCK and BMAL1 bHLH domains | Conserved DNA-binding residues in basic region |

| PAS-A | Typical PAS fold with five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet and flanking α-helices | Domain-swapped helical interface with A'α helix | Hydrophobic residues (Phe104, Leu105, Leu113 in CLOCK) |

| PAS-B | Canonical PAS domain structure connected to PAS-A by flexible linker | Primarily mediated by ~26Å translation | Less conserved than PAS-A interfaces |

| Linkers | L1 (bHLH-PAS-A): ~15 residues in BMAL1; L2 (PAS-A-PAS-B): ~15 residues | Varies between subunits; CLOCK L2 buried at interface | Differential flexibility between subunits |

PAS Domain Interfaces

PAS-A Dimerization Interface

The PAS-A domains of CLOCK and BMAL1 adopt typical PAS folds but mediate heterodimerization through a domain-swapped helical interface [9]. Both PAS-A domains contain an N-terminal flanking helix (A′α) external to the canonical PAS-domain fold. These A′α helices pack between the β-sheet faces of the opposing subunits: the CLOCK PAS-A A′α helix contacts the β-sheet face of BMAL1 PAS-A, while the BMAL1 PAS-A A′α helix interacts with the β-sheet face of CLOCK PAS-A [9].

This interface is largely mediated by conserved hydrophobic interactions. In CLOCK, Phe104, Leu105, and Leu113 on the A′α helix contact a hydrophobic region on BMAL1 PAS-A comprising Leu159 (strand Aβ), Thr285 and Tyr287 (Hβ), and Val315 and Ile317 (strand Iβ) [9]. A similar interface exists between the BMAL1 A′α helix and CLOCK PAS-A domain. The two PAS-A domains form a parallel dimer with an extensive buried surface area of approximately 1950 Ų, featuring topologically complex interfaces between subunits.

PAS-B Arrangement and Linker Flexibility

The PAS-B domains are connected to their respective PAS-A domains by ~15 residue linkers (L2), though the conformation and flexibility of these linkers differ between subunits [9]. In CLOCK, a substantial portion of L2 is buried at the subunit interface and is well-ordered. In contrast, the BMAL1 L2 linker is solvent-exposed and highly flexible, as indicated by high atomic displacement parameters (B-factors) [9]. The PAS-B domains of CLOCK and BMAL1 are related primarily by a ~26Å translation, further contributing to the overall asymmetry of the heterodimer.

Figure 1: Domain Organization and Interaction Interfaces in the CLOCK:BMAL1 Heterodimer. The complex shows extensive domain intertwining with three major interaction interfaces between corresponding domains. Both subunits contain bHLH, PAS-A, and PAS-B domains connected by flexible linkers (L1 and L2).

Transcriptional Activation via E-Box Elements

DNA Binding Mechanism

The CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer activates transcription by binding to canonical E-box sequences (CACGTG) present in the promoters of target genes [9] [12]. The bHLH domains of both subunits mediate DNA binding, with the basic regions making direct contacts with the E-box sequence. Experimental assays demonstrate that CLOCK:BMAL1 binds to E-box elements from the mPer1 and mPer2 promoters with high affinity, exhibiting dissociation constants (Kd) of approximately 10 nM [9].

CLOCK:BMAL1 binding to E-box elements exhibits circadian rhythmicity in vivo, with peak binding occurring during the daytime in mammals [12]. This rhythmic DNA binding drives daily oscillations in the transcription of core clock genes (Per1, Per2, Cry1, Cry2) and clock-controlled output genes such as Dbp [12] [13]. At the Dbp locus, CLOCK:BMAL1 binding is highly circadian and strictly dependent on the heterodimerization of both subunits [13].

Chromatin Remodeling and Transcriptional Regulation

Upon binding to E-box elements, CLOCK:BMAL1 recruits chromatin-modifying enzymes and components of the transcriptional machinery to activate gene expression [3] [14]. This recruitment promotes a series of epigenetic modifications that create a transcriptionally permissive environment:

- Histone acetylation: CLOCK:BMAL1 recruits histone acetyltransferases p300 and CBP, mediating acetylation of H3K9 and H3K27 [14]

- Histone methylation: Recruitment of histone methyltransferases MLL1 and MLL3 promotes tri-methylation of H3K4 [14]

- Nucleosome remodeling: CLOCK:BMAL1 binding promotes rhythmic nucleosome removal, generating a chromatin landscape favorable for transcription factor binding [14]

These chromatin transitions are particularly well-characterized at the Dbp locus, where CLOCK:BMAL1 binding coincides with rhythmic acetylation of Lys9 on histone H3, trimethylation of Lys4 on histone H3, and reduced histone density during the activation phase [12]. During repression, these permissive marks are replaced by dimethylation of Lys9 on histone H3, binding of heterochromatin protein 1α, and increased histone density [12].

Dynamic Binding and Proteasome-Dependent Regulation

CLOCK:BMAL1 associations with chromatin are highly dynamic and display proteasome-dependent fluctuations [13]. Real-time imaging of BMAL1 binding to tandem arrays of Dbp repeats reveals that BMAL1-CLOCK interactions with E-boxes are extremely unstable, with rapid binding and dissociation events even at peak transcriptional times [13].

Proteasome inhibition prolongs the residence time of BMAL1-CLOCK on chromatin but paradoxically attenuates transcription of target genes like Dbp [13]. This suggests that rapid turnover of the activator complex is required for continuous transcription, leading to the "Kamikaze activator" model where CLOCK:BMAL1 undergoes rapid degradation once bound to chromatin to enable multiple rounds of initiation [13].

Table 2: CLOCK:BMAL1 Target Genes and Regulatory Functions

| Target Gene | E-box Location | Function | Regulatory Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per1, Per2 | Promoter regions | Core clock components | Negative feedback regulators |

| Cry1, Cry2 | Promoter regions | Core clock components | Negative feedback regulators |

| Dbp | Multiple intragenic and extragenic sites | Output regulator | Circadian transcription regulation |

| Rev-erbα/β | Promoter regions | Nuclear receptors | Stabilization of circadian oscillation |

| Avp | Promoter E-box | Neuropeptide signaling | SCN output signal |

Experimental Methodologies and Research Tools

Structural Biology Approaches

Protein Expression and Purification

For structural studies, researchers expressed N-terminal His-tagged mouse CLOCK (residues 26-384) and native mouse BMAL1 (residues 62-447) constructs in Sf9 insect cells using baculovirus-mediated co-expression systems [9]. The complex was co-purified using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography to obtain stable heterodimeric protein suitable for crystallographic analysis [9].

Crystallization and Structure Determination

Crystals of CLOCK:BMAL1 were obtained that diffracted to 2.3Å resolution at synchrotron sources [9] [11]. The phase problem was solved using the single wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) method with selenomethionine-labeled CLOCK:BMAL1 crystals [9]. Data collection and refinement statistics are available in the original publication (PDB ID: 4F3L) [11].

DNA Binding Assays

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were used to characterize CLOCK:BMAL1 binding to E-box sequences [9]. These assays confirmed high-affinity binding (Kd ~10 nM) to oligonucleotides containing the canonical E-box sequence (CACGTG) from mPer1 and mPer2 promoters [9].

Live-Cell Imaging of Chromatin Binding

To investigate the kinetics of BMAL1 binding to target genes in real time, researchers generated cell lines harboring tandem arrays of Dbp repeats and monitored binding of fluorescent BMAL1 fusion proteins using time-lapse microscopy [13]. This approach revealed the highly dynamic, proteasome-dependent nature of CLOCK:BMAL1 chromatin interactions.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for CLOCK:BMAL1 Functional and Structural Characterization. A multi-step approach combining biochemical, structural, and cell biological methods is essential for comprehensive analysis of CLOCK:BMAL1 function.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CLOCK:BMAL1 Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Experimental Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLOCK:BMAL1 Protein Constructs | Mouse residues 26-384 (CLOCK) and 62-447 (BMAL1) | Structural studies and in vitro assays | bHLH-PAS-A-PAS-B domains with N-terminal His tag on CLOCK |

| E-box Oligonucleotides | Canonical sequence: CACGTG from mPer1/mPer2 promoters | DNA binding assays (EMSA) | High-affinity binding (Kd ~10 nM) |

| Sf9 Insect Cell System | Baculovirus-mediated co-expression | Protein production for structural studies | Proper folding and heterodimer formation |

| DBP Reporter Cell Line | Tandem arrays of Dbp repeats with luciferase | Real-time binding and transcription imaging | Monitoring dynamic binding and transcriptional activity |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | RRE element deletion in Bmal1 promoter | Functional studies of transcriptional regulation | Disruption of RRE-mediated feedback loop |

Functional Significance in Circadian Regulation

Role in Core Circadian Feedback Loops

The CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer initiates the core negative feedback loop of the mammalian circadian clock [9] [3]. By activating transcription of Per and Cry genes, it sets in motion a sequence of events that leads to its own inhibition: PER and CRY proteins accumulate, form complexes, translocate to the nucleus, and directly interact with CLOCK:BMAL1 to repress transcription [9]. As PER and CRY complexes are degraded by specific E3 ubiquitin ligases, repression is relieved, allowing CLOCK:BMAL1 to initiate a new cycle of transcription [9].

This core loop is interlocked with a secondary feedback loop involving ROR and REV-ERB proteins that regulate Bmal1 transcription through ROR response elements (RREs) in its promoter [4] [3]. While this RRE-mediated loop is not essential for rhythm generation, it provides stability and robustness to the circadian system, making it more resistant to perturbations [4].

Integration with Physiological Processes

The CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer serves as a key interface between the core circadian clock and diverse physiological processes. Recent research has revealed non-canonical functions of BMAL1, including formation of a transcriptionally active heterodimer with HIF2A that modulates circadian variations in myocardial injury [15]. This BMAL1-HIF2A complex regulates the rhythmic expression of amphiregulin (AREG), contributing to diurnal patterns in infarct size following myocardial infarction [15].

The heterodimer also participates in regulating numerous other processes, including cell proliferation, DNA damage repair, angiogenesis, metabolic homeostasis, and immune responses [3]. This broad regulatory scope reflects the extensive reach of the circadian system in temporal organization of physiology.

The CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer represents the cornerstone of the mammalian circadian transcriptional machinery. Its unusual asymmetric structure, with extensively intertwined bHLH-PAS domains, facilitates high-affinity binding to E-box elements and recruitment of transcriptional co-activators. The dynamic nature of CLOCK:BMAL1 chromatin interactions, coupled with proteasome-dependent turnover, enables precise temporal control of target gene expression. Continuing research on this essential transcriptional complex promises to yield deeper insights into circadian timekeeping mechanisms and their implications for human health and disease, particularly in developing chronotherapeutic approaches that align treatments with endogenous circadian rhythms for enhanced efficacy and reduced side effects.

The PER:CRY complex constitutes the core repressor arm of the mammalian circadian clock, executing critical negative feedback within the transcription-translation feedback loop (TTFL). This in-depth technical guide synthesizes current mechanistic understanding of PER:CRY heterocomplex formation, its regulated nuclear translocation, and its multifaceted role in repressing CLOCK:BMAL1-driven transcription. We detail the molecular mechanisms of action, from initial cytoplasmic dimerization to active nuclear import and subsequent displacement of activators from DNA. The document provides a comprehensive quantitative analysis of protein dynamics and abundances, standardized experimental methodologies for investigating these processes, and an overview of essential research tools. This resource is intended to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge and technical frameworks necessary to advance investigations into circadian biology and its therapeutic applications.

The mammalian circadian clock is a cell-autonomous oscillator that coordinates physiological processes with the 24-hour solar cycle. At its core is the transcription-translation feedback loop (TTFL), where the PER:CRY complex functions as the primary negative regulator [2] [3]. The heterodimeric transcription factor CLOCK:BMAL1 activates the expression of numerous clock-controlled genes, including the Period (Per1, Per2, Per3) and Cryptochrome (Cry1, Cry2) genes [3]. Following translation, PER and CRY proteins form heterocomplexes in the cytoplasm. Their subsequent regulated nuclear translocation is a critical, rate-limiting step for the negative feedback process. Within the nucleus, the PER:CRY complex suppresses its own transcription by inhibiting the transcriptional activity of CLOCK:BMAL1, thereby completing the feedback loop with a period of approximately 24 hours [16] [2]. This review dissects the molecular machinery governing the formation, transport, and repressive function of the PER:CRY complex, providing a technical foundation for research and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanism of PER:CRY Complex Formation and Nuclear Translocation

Cytoplasmic Complex Assembly and Phosphorylation Primitives

Following their translation, PER and CRY proteins dimerize in the cytoplasm. This interaction is facilitated by specific protein domains and is a prerequisite for the efficient nuclear entry of the complex. While both proteins can contain nuclear localization signals (NLS), the primary interaction with the nuclear import machinery is mediated by PER proteins [17]. Casein kinases, particularly CK1δ/ε, play a pivotal role in priming the complex for nuclear translocation and subsequent activity by phosphorylating PER proteins. This phosphorylation occurs on specific residues and can influence the stability, interaction capability, and subcellular localization of the complex [16].

KPNB1-Mediated Nuclear Import

The regulated nuclear entry of the PER:CRY complex is primarily mediated by KPNB1 (Importin β), a key nuclear import receptor [17]. RNAi depletion of KPNB1 results in the cytoplasmic trapping of PER proteins and PER:CRY complexes, effectively blocking their nuclear entry and abolishing circadian rhythmicity in human cells [17]. KPNB1 interacts more strongly with PER proteins than with CRY proteins, indicating that PER serves as the primary cargo for nuclear import [17]. This nuclear transport occurs in a circadian fashion, with the interaction peaking when the repressor complex is required in the nucleus. Notably, KPNB1 directs this nuclear transport independently of its classical partner, importin α, revealing a specific and dedicated pathway for the core clock repressors [17]. The conservation of this mechanism is highlighted by the fact that inducible inhibition of the Drosophila importin β homolog in lateral neurons abolishes circadian behavior in flies [17].

Table: Key Proteins in PER:CRY Nuclear Translocation

| Protein | Role in Translocation | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| KPNB1 (Importin β) | Primary nuclear import receptor | Binds directly to PER; essential for nuclear entry of PER:CRY complex; functions independently of importin α [17]. |

| PER1/PER2 | Primary cargo for import machinery | Contains functional NLS; direct interaction with KPNB1 is crucial for complex translocation [17]. |

| CRY1/CRY2 | Cooperative partner in complex | Enhances complex formation; its presence can influence the efficiency of PER nuclear localization [17]. |

| CK1δ/ε | Kinase priming the complex | Phosphorylates PER, which can influence complex stability and its readiness for nuclear import and function [16]. |

Dynamic Nuclear Localization and Protein Mobility

Once in the nucleus, the dynamics of PER:CRY complexes are more intricate than previously thought. Quantitative live-cell imaging of endogenously tagged proteins in mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) slices reveals a spectrum of spatio-temporal behaviors [18]. Contrary to the simple model where PER and CRY are always complexed in the same place and time, they are often segregated in circadian time and cellular space [18]. Measurements of nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (Nuc:Cyto) ratios show that PER2 is the least nuclear of the core repressors (~27% cytoplasmic), followed by CRY1 (~9% cytoplasmic) [18]. Furthermore, Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) analyses demonstrate that these proteins exist in multiple mobility pools within the nucleus. PER2 has the smallest immobile fraction (~35%), indicating it is the most dynamic, while CRY1 has a larger immobile fraction (~50%), consistent with its role in stable binding to transcriptional complexes [18]. This suggests a model where PER2 and CRY1 may interact transiently at specific sites and times to execute repressive functions, rather than existing as a stable, monolithic complex throughout the night.

Mechanisms of Transcriptional Repression

The PER:CRY complex employs two distinct but complementary mechanisms to repress CLOCK:BMAL1-mediated transcription: a blocking mechanism and a displacement mechanism.

Blocking Repression by CRY

The CRY-mediated "blocking" repression occurs when CRY (primarily CRY1) directly binds to the CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer while it is still associated with E-box DNA [16]. This interaction, which involves the PAS domain core of CLOCK:BMAL1 and the BMAL1 transactivation domain, leaves the DNA binding intact but sterically hinders the recruitment of essential transcriptional co-activators [19]. This mechanism effectively shuts down transcription without evicting the activator complex from the chromatin.

Displacement Repression by the PER:CRY Complex

The PER:CRY-mediated "displacement" repression is a more active process that results in the physical removal of the CLOCK:BMAL1 complex from E-box elements [16]. This process is critically dependent on the kinase CK1δ [16]. The current model posits that the PER:CRY complex recruits CK1δ to CLOCK:BMAL1-bound promoters. PER2 contains specific casein kinase binding domains (CKBDs), and mutations in these domains abolish displacement repression [16]. Once localized, CK1δ phosphorylates CLOCK at multiple sites, which acts as a signal for the dissociation of the entire CLOCK:BMAL1 complex, along with CRY, from the DNA [16]. This phosphorylation-dependent displacement is a crucial step for the robust cycling of the molecular clock.

Table: Modes of Transcriptional Repression by the PER:CRY Complex

| Repression Mode | Key Effector | Molecular Action | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking | CRY1 | Binds CLOCK:BMAL1 on DNA; prevents co-activator recruitment [16] [19]. | Transcriptional inhibition without complex displacement. |

| Displacement | PER:CRY with CK1δ | Recruits CK1δ to promoters; phosphorylates CLOCK; dissociates complex from DNA [16]. | Physical removal of CLOCK:BMAL1 from E-box. |

Diagram: Mechanism of PER:CRY Nuclear Translocation and Transcriptional Repression. The diagram illustrates the key steps from complex formation in the cytoplasm to the two distinct modes of repression (blocking and displacement) in the nucleus.

Quantitative Dynamics of Core Clock Proteins

A comprehensive understanding of the circadian clock requires quantitative data on the abundance, localization, and interactions of its core components.

Protein Abundance and Stoichiometry

Recent studies using knock-in fluorescent reporter mice have quantified the absolute abundances of core clock proteins in native tissues. In SCN neurons, CRY1 and BMAL1 are present at levels that match or exceed those of PER2, positioning PER2 as a potential limiting factor for repressive complex formation [18]. The maximum amplitude of PER2 cycling is approximately 12,000 copies per cell in fibroblasts [19]. The stoichiometric balance between activators and repressors is critical for proper clock function, and even small perturbations can alter the circadian period.

Binding Kinetics and Residence Times

The interaction dynamics between clock proteins and DNA are fundamental to the clock's timing mechanism. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) and FRAP experiments have quantified that the CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer has a DNA residence time of approximately 4.13 seconds [19]. This residence time is dependent on functional DNA-binding domains, as demonstrated by the significantly reduced residence time (2.83 s) of a BMAL1 DNA-binding mutant (L95E) [19]. The repressive PER:CRY complex functions, in part, by altering these binding kinetics. Increasing concentrations of PER2:CRY1 promote the removal of BMAL1:CLOCK from DNA, thereby enhancing the complex's ability to move to new target sites and redistributing the finite pool of activators [19].

Table: Quantitative Dynamics of Core Circadian Proteins in the Nucleus

| Protein / Complex | Quantitative Measure | Value / Finding | Technical Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| PER2 | Nuclear:Cytoplasmic Ratio (Mean) | ~4 (Least nuclear) [18] | Quantitative Live-Cell Imaging |

| CRY1 | Nuclear:Cytoplasmic Ratio (Mean) | ~11 (Intermediate) [18] | Quantitative Live-Cell Imaging |

| BMAL1 | Nuclear:Cytoplasmic Ratio (Mean) | ~18 (Most nuclear) [18] | Quantitative Live-Cell Imaging |

| CLOCK:BMAL1 | DNA Residence Time | 4.13 seconds (95% CI, 0.57) [19] | Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) |

| CLOCK:BMAL1 (L95E Mutant) | DNA Residence Time | 2.83 seconds (95% CI, 0.54) [19] | Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) |

| PER2 | Maximum Abundance (Fibroblasts) | ~12,000 copies per cell [19] | Quantitative Imaging / FCS |

| CRY1, BMAL1 vs. PER2 | Relative Molecular Abundance | CRY1 and BMAL1 levels match or exceed PER2 [18] | Quantitative Live-Cell Imaging |

Essential Research Tools and Methodologies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating the PER:CRY Complex

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Key Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Knock-in Fluorescent Reporter Mice | Enables live imaging of endogenous protein localization, abundance, and dynamics in native tissues (e.g., SCN slices). | PER2::Venus; CRY1::mRuby3; Venus::BMAL1 mouse lines [18] [19]. |

| CK1δ/ε Inhibitors | Pharmacological tool to dissect the role of kinase activity in PER phosphorylation and complex displacement. | PF670462 (CK1δ/ε inhibitor) blocks PER-mediated displacement of CLOCK:BMAL1 from DNA [16]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Knockout | Generation of cell lines lacking specific clock components to study their necessity in the TTFL. | Per1/2-/-; Ck1δ-/- cells show abolished PER-mediated displacement [16]. |

| Inducible Nuclear Transport System | Controlled, acute delivery of clock proteins to the nucleus to study direct, downstream effects. | PER2–Estrogen Receptor fusion protein (PER2-ER*) activated by 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) [16]. |

| Dominant-Negative Mutants | To study the function of specific protein domains or interactions without full gene knockout. | BMAL1 L95E (DNA-binding mutant) reduces DNA residence time and transcriptional output [19]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for E-box Binding Dynamics

Purpose: To quantify the temporal binding of core clock components (CLOCK, BMAL1, CRY) to specific E-box promoter elements (e.g., on the Nr1d1 gene) in response to PER:CRY nuclear entry [16].

Detailed Workflow:

- Cell System: Use a genetically modified cell line (e.g., Per1/2-/- MEFs) stably expressing an inducible nuclear protein like PER2-ER*.

- Treatment & Crosslinking: At desired circadian times or after induction of nuclear entry (e.g., with 4-OHT), treat cells with formaldehyde to crosslink proteins to DNA.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and sonicate chromatin to shear DNA into fragments of 200-1000 bp.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with validated antibodies specific to the protein of interest (e.g., anti-BMAL1, anti-CLOCK, anti-CRY1) or control IgG. Capture antibody-chromatin complexes.

- Washing, Elution, and Reverse Crosslinking: Wash beads stringently, elute the complexes, and reverse the crosslinks by heating.

- DNA Purification and Analysis: Purify the DNA and analyze the enrichment of the target E-box sequence using quantitative PCR (qPCR). Compare to input DNA and IgG controls.

Key Application: This protocol can be used with kinase inhibitors (e.g., PF670462) to demonstrate the requirement of CK1δ activity for the PER-mediated displacement of CLOCK:BMAL1 from DNA [16].

Live-Cell Protein Dynamics via Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP)

Purpose: To measure the mobility and binding kinetics (e.g., DNA residence time) of fluorescently tagged clock proteins in living cells [19].

Detailed Workflow:

- Cell Preparation: Use cells (e.g., NIH/3T3 fibroblasts) expressing fluorescent fusion proteins (e.g., BMAL1::EGFP) via lentiviral transduction or derived from knock-in models.

- Image Acquisition: Place cells on a confocal microscope with an environmental chamber (37°C, 5% CO₂). Select a nucleus for analysis.

- Photobleaching: Define a region of interest (ROI) within the nucleus and subject it to a high-intensity laser pulse to bleach the fluorescence in that area.

- Recovery Monitoring: Immediately after bleaching, capture images of the entire nucleus at low laser power at regular short intervals (e.g., every 0.5-1 s) to track the fluorescence recovery as unbleached molecules diffuse into the bleached area.

- Data Analysis: Normalize fluorescence intensities in the bleached ROI relative to the whole nucleus and a background region. Fit the recovery curve to an appropriate reaction-diffusion model to calculate the half-time of recovery (t₁/₂) and the immobile fraction. The dissociation rate ((k_{OFF})) derived from the fit is the reciprocal of the residence time.

Key Application: This method revealed that co-expression of CLOCK increases BMAL1's DNA residence time and that this requires BMAL1's DNA-binding domain [19].

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for ChIP. This flowchart outlines the key steps in a Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay to study clock protein binding to DNA.

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The molecular clock's pervasive control over physiology makes the PER:CRY complex and its regulators a compelling target for therapeutic intervention. Disruption of circadian rhythms is implicated in a wide range of human pathologies, including cancer, metabolic disorders, and inflammatory diseases [3]. The kinases that regulate the repressor complex, particularly CK1δ/ε, have been identified as potential drug targets. For instance, modulating CK1δ activity could theoretically reset the phase of the circadian clock in shift-work disorders or certain sleep phase syndromes. Furthermore, the nuclear translocation step mediated by KPNB1 represents another node for potential pharmacological manipulation [17]. A deep, quantitative understanding of the protein-protein interactions, stoichiometries, and kinetics described in this guide is a prerequisite for the rational design of small molecules or other therapeutic agents that can precisely tune the clock's timing and output without completely disrupting its oscillation.

In mammalian circadian biology, the core feedback loop formed by the CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimer and its repression by PER/CRY proteins represents a fundamental oscillator. However, the robustness of the 24-hour timekeeping system is critically dependent on an interlocking auxiliary loop that provides stability and resilience. This review focuses on the pivotal role of two families of orphan nuclear receptors—REV-ERBs (α and β) and RORs (α, β, and γ)—in constituting this auxiliary loop through their competitive regulation of Bmal1 transcription. Within the context of broader molecular clock research on PER, CRY, BMAL1, and CLOCK proteins, understanding this RORE-mediated regulatory mechanism provides crucial insights into circadian function and its therapeutic applications.

The molecular clock operates as a network of interconnected feedback loops rather than a simple cyclic pathway. While the core E-box-mediated loop, wherein CLOCK and BMAL1 activate Per and Cry transcription with subsequent repression by PER and CRY proteins, generates basic oscillations, the auxiliary RORE-mediated loop stabilizes these rhythms and confers resistance to perturbation [20] [4]. This review synthesizes current understanding of how REV-ERB and ROR proteins compete for regulatory control of Bmal1, examines experimental evidence establishing this loop's stabilizing function, and explores the translational implications for circadian-related therapeutics.

Molecular Mechanism of the RORE-Mediated Feedback Loop

The Core Regulatory Competition at ROREs

The fundamental mechanism governing the auxiliary circadian loop involves competitive binding at specific DNA sequences known as ROR response elements (ROREs) within the Bmal1 promoter region. These ROREs, highly conserved across mammalian species, serve as the molecular battleground for opposing transcriptional regulators [4].

Transcriptional Repression by REV-ERBs: REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ function as constitutive transcriptional repressors due to their unique structural deficiency—they lack the C-terminal activation function 2 (AF-2) domain typically responsible for coactivator recruitment [20] [21]. Instead, REV-ERBs recruit corepressor complexes, including NCoR (nuclear receptor corepressor), to ROREs, leading to histone deacetylation, chromatin condensation, and transcriptional silencing of Bmal1 [20] [21]. REV-ERBs can bind to ROREs as monomers recognizing a single AGGTCA half-site with a 5' AT-rich extension, or as homodimers binding to direct repeat elements [20].

Transcriptional Activation by RORs: In contrast, RORα, RORβ, and RORγ function as constitutive transcriptional activators that bind to the same RORE sequences as REV-ERBs [20]. RORs possess an intact AF-2 domain and recruit coactivators to the Bmal1 promoter, driving its transcription independently of external ligands [20] [21]. The different ROR isoforms exhibit distinct tissue expression patterns, suggesting potential tissue-specific fine-tuning of this regulatory mechanism [20].

The dynamic balance between REV-ERB and ROR activity creates a rhythmic pattern of Bmal1 transcription that is phase-opposed to the expression of Per, Cry, and Rev-erb genes themselves [22] [20]. This antiphase relationship is fundamental to the circadian oscillator, creating complementary transcriptional waves that reinforce the approximately 24-hour cycle.

Integration with the Core Circadian Clock

The RORE-mediated auxiliary loop does not operate in isolation but is intricately interconnected with the core E-box-mediated feedback loop:

Upstream Regulation: The expression of both Rev-erb and Ror genes is itself regulated by the CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimer through E-box elements in their promoters [20] [23]. This creates an interlocking architecture where the core loop regulates components of the auxiliary loop, which in turn regulates a essential component (BMAL1) of the core loop.

Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns: REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ have overlapping expression patterns in metabolic tissues such as liver, adipose, skeletal muscle, and brain [20]. ROR isoforms display more distinct expression profiles, with RORα being widely expressed, RORβ restricted primarily to the central nervous system, and RORγ highly expressed in immune cells and certain metabolic tissues [20]. This variation suggests tissue-specific customization of the auxiliary loop function.

Table 1: Characteristics of REV-ERB and ROR Nuclear Receptors

| Receptor | Function | Expression Pattern | DNA Binding | Coregulator Recruitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REV-ERBα | Transcriptional repressor | Ubiquitous; liver, adipose, muscle, brain | Monomer/homodimer to RORE | Binds corepressors (NCoR) |

| REV-ERBβ | Transcriptional repressor | Pineal gland, pituitary, thyroid; overlapping with REV-ERBα | Monomer/homodimer to RORE | Binds corepressors (NCoR) |

| RORα | Transcriptional activator | Liver, skeletal muscle, skin, lung, adipose, brain, thalamus | Monomer to RORE | Binds coactivators |

| RORβ | Transcriptional activator | Central nervous system (sensory pathways), retina, pineal gland | Monomer to RORE | Binds coactivators |

| RORγ | Transcriptional activator | Thymus (RORγt isoform), liver, skeletal muscle, adipose, kidney | Monomer to RORE | Binds coactivators |

Experimental Evidence for the Stabilizing Function

Genetic Deletion Studies

The functional significance of the RORE-mediated loop has been elucidated through a series of genetic manipulation studies in cell and animal models:

RRE Element Deletion: A landmark 2022 study established mutant cells and mice with specific deletion of the two RRE elements in the Bmal1 promoter (ΔRRE mutants) [4]. These mutants lost rhythmic Bmal1 transcription, demonstrating that these specific elements are essential for its circadian expression. Surprisingly, these mutants maintained apparently normal circadian rhythms in both locomotor behavior and PER2 protein expression, indicating that Bmal1 mRNA cycling is not absolutely required for oscillator function [4]. However, mathematical modeling combined with experimental perturbation revealed that the circadian period and amplitude in ΔRRE mutants were significantly more susceptible to disturbance of CRY1 protein rhythm, demonstrating the stabilizing function of this loop [4].

REV-ERB Deletion Studies: Single knockout of Rev-erbα produces relatively mild circadian phenotypes, while constitutive double knockout of both Rev-erbα and Rev-erbβ is developmentally lethal [23] [24]. However, inducible double knockout in adult mice or cell models reveals that REV-ERBs are required for rhythmic Bmal1 expression but not for core clock oscillation [23] [24]. A 2019 study using REV-ERBα/β double knockout embryonic stem cells found that PER2 expression rhythms persisted normally despite abrogated Bmal1 mRNA cycling and constitutive BMAL1 protein expression [23]. Global gene expression analysis revealed that REV-ERB deficiency dramatically altered the rhythmic expression of output genes while preserving core clock gene oscillations [23].

ROR Functional Studies: Genetic studies of RORs have been complicated by functional redundancy among isoforms and severe developmental phenotypes in single mutants [24]. However, experimental evidence indicates that RORs contribute to Bmal1 expression amplitude but are dispensable for its rhythm, with REV-ERBs playing a more dominant role in generating transcriptional oscillation [24].

Table 2: Phenotypic Consequences of Genetic Perturbations to the RORE-Mediated Loop

| Genetic Model | Effect on Bmal1 Transcription | Effect on Core Clock Rhythms | System-Level Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔRRE Bmal1 promoter | Abrogated rhythmic transcription [4] | Persisting but destabilized oscillations; increased susceptibility to CRY perturbation [4] | Normal period under constant conditions but altered responses to metabolic challenge [4] |

| REV-ERBα/β DKO | Constitutive, elevated expression [23] | Sustained PER2 rhythmicity; altered output gene rhythms [23] | Disrupted metabolic and immune gene expression; developmental lethality in constitutive KO [23] |

| RORα mutant (staggerer) | Reduced amplitude [24] | Mild period alterations [24] | Cerebellar ataxia, metabolic phenotypes [24] |

| Single REV-ERBα KO | Mildly affected rhythm [24] | Normal period with increased variability [24] | Metabolic alterations [24] |

Quantitative Assessments of Loop Function

Mathematical modeling integrated with experimental data has provided quantitative insights into the stabilizing function of the RORE-mediated loop:

Kim-Forger Model Simulations: Computational modeling of the ΔRRE mutant circadian system, which eliminates rhythmic Bmal1 transcription, revealed that BMAL1 protein phosphorylation rhythms persist despite constitutive mRNA expression [4]. This post-translational regulation provides a compensatory mechanism that maintains rhythmic function but with reduced resilience to perturbation.

Amplitude and Period Stability: Modeling predicts and experiments confirm that the interlocked loop architecture provides significant resistance to both internal noise and external perturbation [4]. Systems with intact RORE-mediated regulation maintain stable periodicity across a wider range of parameter variations and exhibit higher amplitude oscillations critical for robust rhythmic output.

Research Methods and Experimental Approaches

Key Methodologies for Investigating the REV-ERB/ROR/BMAL1 Axis

The molecular intricacies of the auxiliary stabilizing loop have been elucidated through a range of specialized experimental techniques:

Circadian Bioluminescence Reporter Assays: Real-time monitoring of circadian rhythms using luciferase reporters under control of the Bmal1 promoter (containing RRE elements) or other clock gene promoters provides high-temporal resolution data on circadian function [6] [4] [24]. This approach typically involves transfection of reporter constructs into cells such as NIH3T3 fibroblasts, followed by continuous bioluminescence recording using photomultiplier tubes or imaging systems [6]. Treatment with small molecule modulators of REV-ERB or ROR activity during recording can dynamically assess their effects on circadian parameters.

Genetic Manipulation Approaches: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing has enabled precise deletion of RRE elements from endogenous Bmal1 promoters in cells and mice [4]. Conditional knockout strategies using Cre-loxP systems have overcome the developmental limitations of constitutive REV-ERB double knockouts, allowing temporal control of gene deletion in specific tissues or at particular developmental stages [23]. RNA interference provides complementary approaches for transient knockdown of REV-ERB or ROR expression in cell models [24].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): ChIP assays using antibodies against REV-ERB or ROR proteins demonstrate their direct binding to RORE elements in the Bmal1 promoter across the circadian cycle [22]. Combination with quantitative PCR reveals rhythmic binding patterns that correspond to transcriptional activity.

Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analyses: Comprehensive RNA sequencing at multiple circadian time points in wild-type versus mutant models identifies genes dependent on REV-ERB/ROR function [23]. Western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies enables tracking of BMAL1 phosphorylation rhythms independent of transcription [6] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating REV-ERB/ROR/BMAL1 Regulation

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| ΔRRE mutant models | Cells or mice with deleted RRE elements in Bmal1 promoter | Testing necessity of RREs for rhythmic transcription [4] |

| REV-ERBα/β DKO cells | Double knockout embryonic stem cells or differentiated cells | Assessing functional redundancy of REV-ERB isoforms [23] |

| Bmal1::luciferase reporter | Luminescent reporter of Bmal1 promoter activity | Real-time monitoring of RORE-mediated transcription [4] |

| PER2::LUCIFERASE knock-in | Endogenous reporter of core clock function | Monitoring core oscillator robustness during RORE manipulation [4] [23] |

| SR9009/SR9011 | REV-ERB agonists that increase repressive activity | Pharmacological enhancement of REV-ERB function [20] [21] |

| GSK4112 | REV-ERB agonist used in experimental settings | Chemical tool for modulating REV-ERB activity [20] |

| ROR inverse agonists | Compounds that suppress ROR transcriptional activity | Reducing ROR-mediated activation of Bmal1 [20] [21] |

Structural and Pharmacological Aspects

Molecular Recognition and Ligand Binding

The REV-ERB and ROR receptors, once classified as orphan nuclear receptors, have now been deorphanized, revealing intriguing structural features that inform their circadian functions:

REV-ERB Ligand Binding: Heme has been identified as the endogenous ligand for both REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ [20] [21]. Heme binding to the REV-ERB ligand-binding domain (LBD) enhances its interaction with the NCoR corepressor, thereby strengthening its repressive function. The LBD of REV-ERBs lacks the canonical AF2 helix, making them constitutive repressors incapable of activating transcription [20]. This structural deficiency explains their unwavering repressive function regardless of ligand binding status.

ROR Ligand Interactions: Cholesterol and cholesterol derivatives have been identified as potential endogenous ligands for ROR receptors, although their precise regulatory role remains under investigation [25] [21]. The binding of oxysterols to RORα and RORγ can modulate their transcriptional activity, often functioning as inverse agonists that reduce receptor activity [21]. The structural flexibility of the ROR LBD allows for regulation by both natural and synthetic ligands.

DNA Recognition Specificity: Both REV-ERBs and RORs recognize similar RORE sequences (typically [A/T]A[A/T]NT[A/G]GGTCA), with the specific sequence and flanking regions determining binding affinity and potential preferences between family members [20] [4]. This shared recognition mechanism enables their competitive regulation of common target genes.

Therapeutic Targeting and Small Molecule Modulation

The pharmacological tractability of REV-ERB and ROR receptors has made them attractive targets for therapeutic development:

REV-ERB Agonists: Synthetic agonists such as SR9009 and SR9011 have been developed that bind to the REV-ERB LBD and enhance its repressive activity [20] [21]. These compounds have shown efficacy in animal models of metabolic disease, inflammation, and circadian disruption, potentially through reinforcing repressive phases of circadian gene expression.

ROR Inverse Agonists: Compounds that suppress the constitutive activity of ROR receptors, particularly RORγt in immune cells, have shown promise for treatment of autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and multiple sclerosis [21]. These agents reduce ROR-mediated transcriptional activation, potentially shifting the balance toward REV-ERB-mediated repression at shared target genes.

The development of isoform-selective modulators remains a challenge due to high sequence conservation within receptor families, but continues to be an active area of pharmaceutical research given the therapeutic potential of targeting the circadian auxiliary loop.

Integration with Physiological Systems and Therapeutic Outlook

Metabolic and Immune Integration

The REV-ERB/ROR/BMAL1 regulatory axis serves as a critical interface between the core circadian clock and multiple physiological systems:

Metabolic Homeostasis: REV-ERB and ROR receptors regulate numerous metabolic genes involved in lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, and mitochondrial function [20] [21]. The circadian expression of these receptors enables temporal coordination of metabolic processes with feeding-fasting cycles. Disruption of this regulatory axis contributes to metabolic disorders, while pharmacological targeting shows promise for treating conditions such as diabetes and obesity [20] [21].

Immune Function: RORγt plays a specialized role in T-helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation and function, making it a compelling target for autoimmune diseases [20] [21]. The circadian regulation of immune function through REV-ERB and ROR receptors creates temporal variations in inflammatory responses that have important implications for chronotherapeutic approaches.

Central Nervous System Function: Both REV-ERB and ROR receptors are expressed in specific brain regions and contribute to neuronal development, neurotransmission, and behavior [26]. Disruption of this regulatory system has been linked to sleep disorders, depression, and neurodegenerative conditions, suggesting potential neuropsychiatric applications for pharmacological modulators.

Chronotherapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The essential stabilizing function of the REV-ERB/ROR/BMAL1 loop and its pharmacological accessibility position it as a promising target for circadian-related therapeutics:

Metabolic Disease: Reinforcing circadian robustness through REV-ERB agonists may counter metabolic disruption associated with shift work, jet lag, or aging [20] [21]. Early preclinical studies demonstrate improved metabolic parameters in animal models.

Inflammatory Disorders: Modulation of the ROR/REV-ERB balance offers opportunities to target the circadian component of inflammatory diseases, potentially with reduced side effects compared to broad immunosuppressants [21].

Personalized Chronotherapy: Understanding individual variations in the RORE-mediated loop function could optimize timing of medications to align with endogenous circadian rhythms, maximizing efficacy and minimizing toxicity.

Future research directions include developing tissue-specific modulators, understanding the crosstalk between this auxiliary loop and other circadian regulatory mechanisms, and exploring the potential of multi-target approaches that simultaneously modulate both the core and auxiliary circadian loops.

Visualizing the Regulatory Network and Experimental Approach

Schematic of REV-ERB/ROR/BMAL1 Regulatory Network and Experimental Methods

The auxiliary stabilizing loop formed by competitive regulation of Bmal1 transcription by REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptors represents a crucial component of the mammalian circadian timing system. While not absolutely required for the generation of circadian oscillations, this RORE-mediated loop provides essential stability, robustness, and temporal precision to the core clockwork. The intricate interconnection between this auxiliary loop and the core E-box-mediated feedback loop creates a resilient network architecture capable of maintaining accurate 24-hour timing despite molecular noise and environmental perturbations.

Ongoing research continues to elucidate the complex interplay between these regulatory systems, their integration with physiological processes, and their potential as therapeutic targets. The development of increasingly sophisticated genetic models and selective pharmacological tools will further advance our understanding of how this auxiliary loop contributes to circadian health and disease, potentially opening new avenues for chronotherapeutic interventions across a spectrum of metabolic, immune, and neurological disorders.

The mammalian circadian clock, a master regulator of physiological rhythms, is orchestrated at its core by a transcription-translation feedback loop (TTFL) involving the CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, and CRY proteins. While genetic mechanisms establish this feedback loop, post-translational modifications (PTMs) provide the critical regulatory layer that confers temporal precision, controls protein stability, and dictates subcellular localization. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of how phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and SUMOylation fine-tune the molecular clockwork. We synthesize current understanding of the enzyme-substrate relationships governing clock protein modifications, present quantitative data on their functional consequences, and detail experimental approaches for their investigation. The growing recognition of PTMs as drug-gable targets underscores their relevance to researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of chronobiology and therapeutic discovery.

The mammalian circadian clock operates through autoregulatory transcriptional-translational feedback loops (TTFLs) that generate ~24-hour rhythms in physiology and behavior. The core positive elements CLOCK (or its paralog NPAS2) and BMAL1 form heterodimers that activate transcription of genes containing E-box enhancer elements, including the period (Per1, Per2) and cryptochrome (Cry1, Cry2) genes [27]. The core negative elements PER and CRY proteins progressively accumulate, form multimeric complexes, and translocate to the nucleus to repress CLOCK:BMAL1 transcriptional activity, thereby closing the negative feedback loop [28] [29]. Additional regulatory loops, such as those involving the nuclear receptors REV-ERB and ROR which regulate Bmal1 transcription, stabilize the core oscillator [28].

However, the transcriptional rhythm alone is insufficient to explain the precision and stability of the circadian clock. Post-translational modifications represent a crucial regulatory layer that controls the timing, stability, localization, and activity of core clock components [27] [29]. These covalent modifications—including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and SUMOylation—create a sophisticated protein modification code that orchestrates clock protein behavior over the daily cycle, determining the speed of the clock, its response to environmental stimuli, and its integration with cellular metabolism [28].

Phosphorylation of Clock Proteins

Phosphorylation is the most extensively studied PTM in the circadian system, primarily regulating protein stability, subcellular localization, and transcriptional activity through the addition of phosphate groups to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues.

Key Kinases and Their Targets

Table 1: Major Kinases and Their Clock Protein Substrates

| Kinase | Clock Substrate | Functional Consequence | Biological Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casein Kinase Iδ/ε (CKIδ/ε) | PER1, PER2, PER3 | Promotes PER degradation via ubiquitination; regulates repressor activity [30]. | Determines period length; mutations associated with familial advanced sleep phase syndrome [27]. |

| c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) | PER2, BMAL1, CLOCK | Stabilizes PER2; regulates transcriptional activity of CLOCK-BMAL1 [27]. | Maintains normal periodicity; mediates light input to the clock [27]. |

| AMP-activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) | CRY1 | Phosphorylates CRY1, priming it for FBXL3-mediated ubiquitination [28]. | Couples metabolic state to clock function; regulates CRY stability [28]. |

| Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 5 (CDK5) | CLOCK | Phosphorylates CLOCK at Thr-451/461, promoting its nuclear localization [29]. | Regulates CLOCK-BMAL1 transactivation activity and phase [29]. |

| Casein Kinase II (CKII) | Unknown | Identified via inhibitor studies as affecting period length [27]. | Potential regulator of cellular clock periodicity. |

Detailed Phosphorylation Mechanisms

PER Phosphorylation: PER proteins undergo progressive phosphorylation throughout the circadian cycle, which is critical for their repressor function and turnover. CKIδ/ε forms stable, stoichiometric complexes with PER proteins, a conserved feature from fungi to mammals [30]. This interaction is mediated by a specific PER-CK1 docking (PCD) site on PER, an α-helical domain containing conserved residues (e.g., V729 and L730 in hPER2). Mutation of these residues abolishes PER-CK1 interaction, leading to hypophosphorylated PER that is stabilized and fails to generate robust PER abundance rhythms. Surprisingly, such mutations in mice do not abolish behavioral rhythms but result in robust short-period locomotor activity, indicating that the clock can function independently of rhythmic PER phosphorylation and abundance, likely through a separate PER-CRY-dependent feedback mechanism [30].

CRY Phosphorylation: The stability of CRY proteins is a major determinant of circadian period length. AMPK phosphorylates CRY1, creating a recognition site for the E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXL3, which then targets CRY for proteasomal degradation [28]. This mechanism directly couples cellular energy status (via AMPK) to the circadian period.

CLOCK and BMAL1 Phosphorylation: The CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer is subject to complex phosphorylation regulation. CLOCK phosphorylation at Ser-446 and Ser-440/441 increases its transactivation activity, while subsequent phosphorylation at Ser-38/42 appears to inhibit activity and promote nuclear export [29]. JNK-mediated phosphorylation of BMAL1 and CLOCK is important for the circadian pacemaker and the light input pathway [27].

Figure 1: Phosphorylation cascades regulating core clock protein stability and activity. CK1-mediated PER phosphorylation promotes its degradation, while JNK stabilizes PER and modifies CLOCK/BMAL1. AMPK phosphorylates CRY, facilitating its recognition by the ubiquitin ligase FBXL3.

Experimental Protocol: Mapping PER-CK1 Interaction

Objective: To identify specific residues on PER2 protein required for stable interaction with Casein Kinase 1 delta (CK1δ).

Methodology:

- Plasmid Constructs: Generate a series of human PER2 (hPER2) expression constructs: a) Full-length, b) Various truncated fragments (e.g., aa 1-500, 501-950), c) Internal deletion mutants, d) Point mutations (e.g., V729G, L730G) within the predicted α-helical domain [30].

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Culture HEK293T cells and transiently co-transfect them with individual hPER2 constructs and a CK1δ expression plasmid.

- Immunoprecipitation (IP): After 24-48 hours, lyse cells. Use an antibody against the tag on hPER2 (e.g., FLAG) to immunoprecipitate hPER2 and its associated proteins from the cell lysate.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve the immunoprecipitated proteins and total cell lysate (input) by SDS-PAGE. Perform Western blotting using antibodies against CK1δ and the tag on hPER2 to detect interaction.

- Structure Prediction: Use computational tools like AlphaFold to predict the secondary structure of the wild-type and mutant hPER2 regions to assess if mutations affect α-helix formation [30].

Interpretation: A loss of CK1δ co-immunoprecipitation with specific hPER2 mutants (e.g., V729G-L730G) indicates those residues are critical for the stable PER-CK1 interaction. The absence of an effect on the predicted α-helix structure confirms the specific role of the residues rather than general structural disruption.

Ubiquitination and Proteasomal Degradation

Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of ubiquitin chains to target proteins, is a principal mechanism controlling the rhythmic abundance of clock proteins, primarily by targeting them for degradation by the 26S proteasome.

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases and Clock Protein Turnover

Table 2: E3 Ubiquitin Ligases Regulating Core Clock Protein Stability

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligase | Clock Substrate | Functional Consequence | Phenotype of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCF^FBXL3^ | CRY1, CRY2 | Targets nuclear CRYs for degradation, reactivating CLOCK:BMAL1 [28]. | Long free-running period; stabilized CRYs; dampened molecular rhythms [28]. |

| SCF^FBXL21^ | CRY1, CRY2 | Counteracts FBXL3 in the nucleus; promotes CRY stability in the cytoplasm [28]. | Short or normal period; partly rescues Fbxl3 mutant phenotype [28]. |

| SCF^β-TRCP^ | PER1, PER2 | Recognizes phosphorylated PER and targets it for degradation [28] [30]. | Dampened or long-period rhythms in fibroblasts; stabilized PERs [28]. |

| HUWE1 / PAM | REV-ERBα | Targets REV-ERBα for degradation [28]. | Stabilized REV-ERBα, altered Bmal1 expression (upon dual knock-down) [28]. |

Mechanism of CRY Ubiquitination

The degradation of CRY proteins is a key determinant of circadian period length, governed by two related F-box proteins: FBXL3 and FBXL21. FBXL3 is predominantly nuclear and constitutively expressed, and it binds to CRY proteins that have been primed by AMPK phosphorylation, leading to CRY ubiquitination and degradation [28]. In contrast, FBXL21 is both nuclear and cytoplasmic, and its expression is circadian. FBXL21 binds CRY with higher affinity than FBXL3 and can protect cytoplasmic CRY from degradation, while in the nucleus it may compete with FBXL3, fine-tuning CRY degradation kinetics [28]. This compartment-specific regulation creates a sophisticated system for controlling the timing of CRY-mediated repression.

Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs)

Deubiquitinating enzymes counteract ubiquitin ligases, adding another layer of regulation. For example, USP2 can deubiquitinate and modulate the levels of several clock proteins, including PER1, CRY1, and BMAL1. Knock-down of Usp2 leads to decreased CRY1 protein levels in the liver and can alter the timing of PER1 intracellular localization [28].

Figure 2: Ubiquitination pathways regulating CRY protein stability. FBXL3 is the primary nuclear ligase promoting CRY degradation. FBXL21 has opposing, compartment-specific roles: it can stabilize CRY in the cytoplasm and compete with FBXL3 in the nucleus. PER binding and AMPK phosphorylation provide additional regulatory inputs.

SUMOylation and Its Role in the Circadian Clock

SUMOylation is a reversible PTM involving the attachment of Small Ubiquitin-like MOdifier (SUMO) proteins to lysine residues, typically modulating protein-protein interactions, stability, and transcriptional activity.

BMAL1 SUMOylation: BMAL1 is SUMOylated on a highly conserved lysine residue (Lys259) in a circadian manner in mouse liver [27]. This modification has been demonstrated to control BMAL1 protein stability and is critical for pacemaker function. Furthermore, BMAL1 SUMOylation promotes the interaction of the CREB-binding protein (CBP) with the CLOCK-BMAL1 complex, facilitating the resetting of the cellular clock in response to serum stimuli [27]. This SUMOylation-dependent recruitment of CBP induces acute activation of CLOCK-BMAL1-mediated Per1 transcription, thereby resetting the cellular clock phase in response to external cues.

Experimental Toolkit for Studying Clock Protein PTMs

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Reagent / Method | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | Identifies direct protein-protein interactions (e.g., kinase-substrate, ligase-substrate). | Used to map the PER-CK1 interaction using truncated and point-mutated PER2 constructs [30]. |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Detects specific phosphorylation events on clock proteins via Western blot or immunofluorescence. | Key for observing circadian rhythms in CLOCK phosphorylation at sites like Ser-38/42 and Ser-440/441 [29]. |

| Kinase/Enzyme Inhibitors | Pharmacological tool to probe the functional role of specific modifying enzymes. | Inhibitors of JNK (SP600125), p38 (SB203580), and CKI (IC261) were used to assess effects on cellular clock periodicity [27]. |

| Mutant Animal Models | In vivo analysis of the physiological consequence of disrupted PTMs. | Fbxl3 knockout mice show long-period locomotor activity rhythms [28]. PER2 PCD-site mutant mice show short-period rhythms [30]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Systematically identifies and maps sites of PTMs (phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation). | Used in circadian liver phosphoproteome studies to identify novel phosphorylation sites on CLOCK [29]. |

| Luciferase Reporter Assays | Measures the transcriptional activity of clock complexes (CLOCK-BMAL1) in live cells. | Used to assess the impact of kinase inhibitors or PTM-disrupting mutations on clock function and period length [27]. |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutics

Understanding the PTM landscape of the circadian clock opens novel avenues for therapeutic intervention. The enzymes that mediate PTMs—kinases, ubiquitin ligases, and deubiquitinases—represent druggable targets for modulating clock function.

Targeted Protein Degradation: The prominence of ubiquitination in clock timing has inspired strategies like PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs). These molecules are small, bifunctional compounds that recruit a target protein (e.g., a pathogenic protein) to an E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to its degradation. While most current PROTACs use a limited set of E3 ligases (e.g., cereblon, VHL), research is actively expanding the E3 ligase toolbox to include others like DCAF16 and KEAP1 [31]. This approach could theoretically be directed against unstable clock proteins or oncogenes under clock control.

Molecular Switches in Drug Delivery: The concept of molecular switches—entities that change state in response to biological triggers—is being leveraged in drug formulation. For instance, pH-sensitive molecular switches can be incorporated into nanoparticle-based drug carriers to release their payload specifically in the acidic microenvironment of tumors, which could include drugs targeting clock-related pathways in cancer cells [32].

AI-Powered Discovery: Artificial intelligence is accelerating drug discovery by predicting protein structures (like clock protein complexes), screening compound libraries, and simulating clinical trials. Resources like the SOAR (Spatial transcriptOmics Analysis Resource) platform provide a "molecular GPS" to understand gene activity and cell interactions in specific tissue contexts, which is crucial for developing clock-targeting therapies with minimal off-target effects [33].