Optimizing Hormone Replacement Therapy in Postmenopausal Women with Type 2 Diabetes: A Comprehensive Review of Efficacy, Safety, and Novel Therapeutic Synergies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) for postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

Optimizing Hormone Replacement Therapy in Postmenopausal Women with Type 2 Diabetes: A Comprehensive Review of Efficacy, Safety, and Novel Therapeutic Synergies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) for postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). It synthesizes recent evidence on the metabolic benefits of HRT, including improved glycemic control and insulin sensitivity, while critically evaluating cardiovascular and oncological risks. The review emphasizes the critical importance of therapy personalization, highlighting the superior safety profile of transdermal estrogen formulations over oral ones in this population. It further explores the 'timing hypothesis' for early intervention and examines emerging data on synergistic effects between HRT and contemporary diabetes medications like GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors. The article concludes by identifying key gaps in the current evidence base and proposing future directions for clinical research and drug development to enhance treatment outcomes for this growing patient demographic.

The Metabolic Interplay: Menopause, Diabetes, and the Rationale for HRT

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary mechanistic links between declining estrogen and the onset of insulin resistance? The decline in estrogen, particularly 17β-estradiol (E2), disrupts glucose homeostasis through multiple interconnected pathways. Estrogen acts primarily through Estrogen Receptor alpha (ERα) to enhance insulin sensitivity in key metabolic tissues. In skeletal muscle, ERα activation promotes glucose uptake and insulin signaling. In the liver, it suppresses gluconeogenesis. In adipose tissue, it regulates lipid storage and inhibits pro-inflammatory adipokine release. The loss of estrogenic signaling leads to increased systemic inflammation, ectopic lipid accumulation in liver and muscle, and impaired insulin receptor signaling [1] [2] [3]. Furthermore, estrogen deficiency is associated with reduced pancreatic β-cell function and survival, compromising insulin secretion [4] [3].

FAQ 2: How does menopause-associated fat redistribution specifically contribute to cardiometabolic risk? Menopause triggers a shift from a gynoid (pear-shaped, peripheral) to an android (apple-shaped, central) fat distribution. This is clinically significant because [5] [2]:

- Visceral Adiposity: Central fat is metabolically active, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) and free fatty acids into the portal circulation. This promotes hepatic insulin resistance and dyslipidemia.

- Dysfunctional Adipose Tissue: The adipocytes in visceral depots are more susceptible to hypertrophy and hypoxia, leading to fibrosis, macrophage infiltration, and a diabetogenic adipokine profile (e.g., reduced adiponectin) [1].

- Ectopic Fat Deposition: When subcutaneous adipose tissue's storage capacity is exceeded, lipids accumulate in the liver, skeletal muscle, and heart, further driving insulin resistance and cardiovascular dysfunction [3].

FAQ 3: What is the "Timing Hypothesis" for Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) and its cardiometabolic benefits? The "Timing Hypothesis" posits that the cardiovascular and metabolic benefits of HRT are maximized, and risks minimized, when therapy is initiated early in the menopausal transition (typically within 10 years of menopause onset and before the age of 60) [4] [3]. In younger, recently postmenopausal women, HRT can improve insulin sensitivity, beta-cell function, and lipid profiles, and may delay the onset of type 2 diabetes (T2DM). In contrast, initiating HRT in older women with established atherosclerosis may exacerbate underlying vascular inflammation and increase the risk of thromboembolic events [6] [4] [7].

FAQ 4: How do different HRT formulations (oral vs. transdermal) impact cardiovascular risk profiles? The route of estrogen administration significantly influences its metabolic and thrombotic effects.

- Transdermal Estrogen: This route is generally preferred for women with T2DM or elevated cardiovascular risk. It avoids first-pass liver metabolism, leading to more stable physiological hormone levels. This results in a more favorable impact on liver-synthesized proteins, with a lower risk of inducing hypertension, thromboembolism, and stroke compared to oral formulations [4] [7].

- Oral Estrogen: The first-pass hepatic effect can be advantageous for improving the lipid profile (e.g., lowering LDL-C) but simultaneously increases the production of pro-coagulant factors and C-reactive protein (CRP), potentially elevating thrombotic risk [4] [3].

Table 1: Comparison of HRT Formulation Impacts on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

| Risk Factor | Transdermal Estrogen | Oral Estrogen |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin Sensitivity | Improves, neutral effect [4] | Improves [3] |

| Thromboembolic Risk | Lower risk [4] [7] | Higher risk [4] |

| Stroke Risk | Neutral or lower risk [7] | Can be increased [4] |

| Lipid Profile | Modest improvement [4] | Greater LDL-C reduction, but can increase triglycerides [3] |

| Hypertension | Neutral effect [4] | Can increase risk [4] |

FAQ 5: What is the role of progestogens in HRT regimens for women with type 2 diabetes? The addition of progestogen is necessary for women with an intact uterus to prevent estrogen-induced endometrial hyperplasia. However, the choice of progestogen is critical as it can modulate the metabolic benefits of estrogen. Some progestogens (e.g., medroxyprogesterone acetate) can attenuate estrogen's positive effects on insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism. Therefore, regimens for women with T2DM should prioritize progestogens with a more neutral metabolic profile, such as micronized progesterone [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Metabolic Phenotypes in Ovariectomized Rodent Models

- Problem: High variability in weight gain, insulin resistance, and fat distribution after ovariectomy (OVX).

- Solution:

- Standardize Diet and Age: Use animals of a consistent age (e.g., 12-16 weeks) and control dietary intake precisely. A high-fat diet post-OVX can amplify and standardize the metabolic phenotype [8].

- Confirm OVX Efficacy: Measure uterine weight at endpoint as a bioassay for successful estrogen depletion. A significant reduction in uterine weight confirms procedure efficacy.

- Control for Timing: Initiate experiments or HRT interventions immediately after OVX to model the "window of opportunity" and avoid the confounding effects of long-established metabolic dysfunction [3].

Challenge 2: Accurately Assessing Tissue-Specific Insulin Resistance In Vivo

- Problem: Whole-body measures like HOMA-IR lack tissue-specific resolution.

- Solution:

- Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp: This is the gold standard. Combine it with radioactive tracers (e.g., 2-deoxyglucose) to precisely quantify glucose disposal rates in specific tissues like skeletal muscle and adipose tissue [3].

- Functional Tissue Analysis: Ex vivo analysis of insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation in muscle, liver, and adipose tissue biopsies provides a direct readout of insulin signaling pathway integrity.

Challenge 3: Modeling the Complex Hormonal Milieu of Perimenopause

- Problem: Most models use sharp, surgical OVX, which does not replicate the gradual, fluctuating hormonal decline of natural menopause.

- Solution:

- The VCD Model: Use 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD) in rodents to induce gradual ovarian follicle depletion, mimicking the hormonal fluctuations and transition period of human perimenopause.

- Longitudinal Sampling: In clinical or large-animal studies, conduct frequent longitudinal hormone level monitoring (estradiol, FSH) to correlate individual hormonal trajectories with metabolic outcomes [2].

Challenge 4: Disentangling the Effects of Aging vs. Estrogen Deficiency

- Problem: It is difficult to determine if observed metabolic deficits are due to aging itself or the loss of ovarian function.

- Solution:

- Use of Young OVX vs. Aged Animals: Compare young OVX rodents with aged, naturally postmenopausal rodents.

- HRT Reversal: If a metabolic parameter (e.g., insulin resistance) is reversed by short-term HRT in an OVX model, it is more likely a direct consequence of estrogen deficiency rather than irreversible aging [3].

- Statistical Control: In human studies, use multivariate regression models to control for age, thereby isolating the independent effect of menopausal status or hormone levels [9].

Synthesis of Key Quantitative Data

Table 2: Impact of Menopausal Status and HRT on Key Cardiometabolic Parameters

| Parameter | Premenopausal State | Postmenopausal State (Untreated) | Postmenopausal State (with HRT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol (E2) Level | 100-250 pg/mL [2] | ~10 pg/mL [2] | Variable (therapy-dependent) |

| HOMA-IR | Reference | Increased by ~13% [4] | Can be reduced by up to 36% in women with T2DM [4] |

| T2DM Incidence | Reference | Increased [6] [10] | Up to 30% reduction in at-risk women [4] [3] |

| LDL-C | Reference | Increases during late perimenopause/early postmenopause [2] | Decreased (oral estrogen > transdermal) [4] [3] |

| Visceral Fat Mass | Reference | Significantly increased [5] [3] | Reduced or prevented [1] [3] |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Metabolic Phenotype in a Murine OVX Model

- Animals: 12-week-old C57BL/6 female mice.

- OVX Surgery: Anesthetize mice. Make a dorsal midline incision, locate and excise the ovaries. Suture muscle and skin. Sham-operated controls undergo identical procedure without ovary removal.

- HRT Intervention: Randomize OVX mice into groups receiving either vehicle, transdermal 17β-estradiol (e.g., 0.1 µg/day patch), or oral conjugated estrogens via gavage. Begin treatment immediately post-surgery.

- Metabolic Monitoring: Monitor body weight and food intake weekly. At 8 weeks post-OVX, perform:

- Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT): Fast mice for 6 hours, inject glucose (2g/kg i.p.), measure blood glucose at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes.

- Insulin Tolerance Test (ITT): Fast mice for 4 hours, inject insulin (0.75 U/kg i.p.), measure blood glucose as in GTT.

- Terminal Analysis: Euthanize mice. Collect blood for hormone/lipid panels. Weigh and snap-freeze metabolic tissues (liver, quadriceps, gonadal/ subcutaneous fat) for molecular analysis. Weigh uteri.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Tissue-Specific Insulin Signaling via Western Blot

- Tissue Lysate Preparation: Homogenize ~50 mg of frozen liver, muscle, or adipose tissue in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Centrifuge and quantify protein concentration.

- Western Blotting: Resolve 30 µg of protein by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane.

- Immunoblotting: Block membrane and probe with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C.

- Targets: Phospho-Akt (Ser473), Total Akt, Phospho-IRβ (Tyr1150/1151), Total IRβ.

- Detection and Analysis: Incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, develop with ECL reagent, and visualize. Quantify band density. Express p-Akt/Akt and p-IR/IR ratios to assess insulin pathway activation.

Protocol 3: Measuring Endogenous Sex Hormones in Postmenopausal Human Serum via LC-MS/MS

- Sample Collection: Draw fasting venous blood. Centrifuge to isolate serum. Store at -80°C.

- Sample Preparation: Thaw samples. Perform liquid-liquid extraction to isolate hormones.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Use a C18 reverse-phase column with a gradient of methanol/water with ammonium acetate.

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate in positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode. Use Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for high specificity. Key analytes: Estradiol, Estrone, Testosterone, Dihydrotestosterone (DHT), Androstenedione [9].

- Quantification: Quantify hormone levels using stable isotope-labeled internal standards and a calibration curve. This method is superior to RIA for low hormone levels in postmenopausal women [9].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

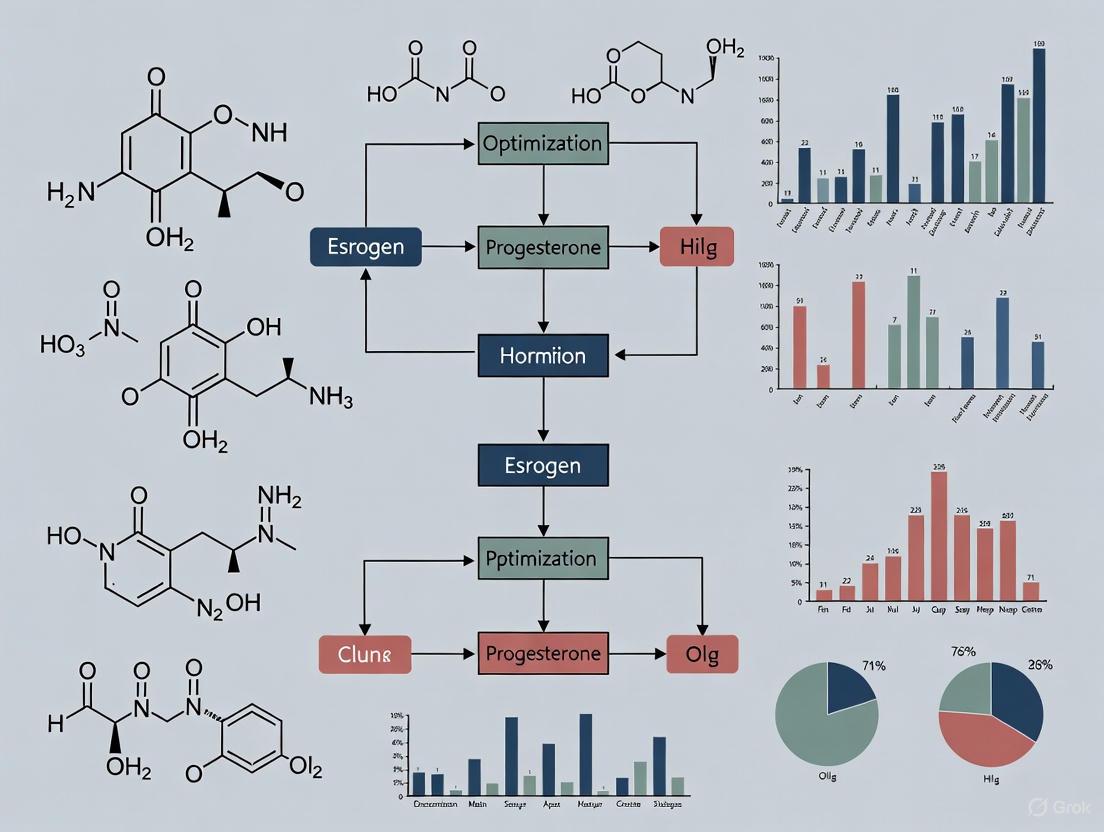

Diagram 1: Estrogen Signaling & Menopausal Disruption in Metabolism (Width: 760px)

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for HRT & Metabolism Research (Width: 760px)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Estrogen-Metabolism Crosstalk

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ovariectomized (OVX) Rodent Models | Preclinical model for surgical menopause; allows for controlled HRT studies. | C57BL/6 mice are common; uterine weight is a critical endpoint for confirming estrogen deficiency [3]. |

| 4-Vinylcyclohexene Diepoxide (VCD) | Chemical to induce gradual ovarian follicle atrophy, modeling human perimenopause. | Provides a more translational model of natural menopause compared to acute OVX. |

| 17β-Estradiol (E2) | The primary endogenous estrogen for in vitro and in vivo replacement studies. | Available in various formulations: pellets for sustained release, injections, or dissolved in drinking water/diet [1]. |

| Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) & Knockout Models | To dissect the specific roles of ERα vs. ERβ in metabolic tissues. | ERα global knockout (αERKO) and tissue-specific (e.g., AdipoERα) mice are vital tools [1] [3]. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Gold-standard for precise quantification of low levels of sex steroids in postmenopausal serum/plasma. | Superior to RIA for sensitivity and specificity in measuring estradiol, estrone, androgens [9]. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | For detecting activation states of insulin signaling pathways in tissue lysates. | Antibodies against p-Akt (Ser473), p-IRβ (Tyr1150/1151) are essential for Western blot analysis. |

| Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp Setup | The definitive in vivo method for quantifying whole-body insulin sensitivity. | Requires programmable infusion pumps, glucose analyzers, and radioactive/stable isotope tracers for tissue-specific disposal rates [3]. |

The age at which a woman experiences natural menopause is a significant determinant of long-term cardiometabolic health. A growing body of evidence establishes early menopause as a potent clinical marker for an increased risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and Metabolic Syndrome (MetS). MetS represents a cluster of conditions—including central obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance—that collectively elevate the risk for cardiovascular disease and T2DM [11] [12]. Understanding this relationship is crucial for developing targeted prevention strategies, particularly in the context of optimizing Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) regimens for women with or at risk for T2DM. This technical resource synthesizes the key epidemiological data, explores underlying mechanisms, and provides practical research guidance for investigators in this field.

Key Epidemiological Findings:

- Metabolic Syndrome Risk: A large-scale study of over 234,000 women found that those experiencing early natural menopause had a 27% increased relative risk of developing MetS compared to those with later menopause [13].

- Type 2 Diabetes Risk: A 2024 meta-analysis of 19 studies concluded that early menopause is associated with a 24% higher odds of developing T2DM (Pooled OR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.09–1.40). The same analysis found a significantly higher hazard of T2DM among women with early menopause (Pooled HR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.05–1.64) [14].

- Disease Severity Link: The relationship with T2DM is not merely temporal; research indicates that women with longer-standing T2DM (>10 years duration) and those with microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy) experience menopause approximately two years earlier than their non-diabetic counterparts [15].

Table 1: Quantified Risk of T2DM and Metabolic Syndrome Associated with Early Menopause

| Condition | Risk Measure | Magnitude of Increase | Source Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Syndrome | Relative Risk | 27% | Large-Scale Cohort [13] |

| Type 2 Diabetes (Odds) | Pooled Odds Ratio (OR) | 24% | Meta-Analysis (19 studies) [14] |

| Type 2 Diabetes (Hazard) | Pooled Hazard Ratio (HR) | 31% | Meta-Analysis [14] |

| Early Menopause Prevalence | Prevalence Ratio | 2.3-fold higher in T2DM vs non-T2DM | Cross-Sectional Study [15] |

Key Pathophysiological Pathways

The link between early menopause and metabolic dysfunction is driven by the decline in estrogen and its multifaceted role in metabolism.

Estrogen Deficiency and Central Metabolism

The decline in estrogen during menopause has a direct impact on body composition and energy balance. Estrogen deficiency is associated with:

- Increased Visceral Adiposity: A redistribution of fat to the abdominal area, independent of age and total body fat [12].

- Reduced Energy Expenditure: A decrease in basal metabolic rate and fat oxidation [3].

- Insulin Resistance: Estrogen enhances insulin sensitivity by modulating insulin receptor expression and insulin signaling. Its deficiency contributes to systemic insulin resistance [3] [4].

The following diagram illustrates the core pathway through which estrogen deficiency leads to T2DM and MetS.

The Bidirectional Relationship

The relationship between menopause and T2DM is complex and often bidirectional. While early menopause increases the risk of T2DM, pre-existing T2DM can also accelerate reproductive aging. One proposed mechanism is that the microvascular complications of diabetes (retinopathy, nephropathy) may damage the highly vascularized ovarian tissue, potentially leading to earlier follicular depletion and menopause [15]. This creates a feedback loop that exacerbates both conditions.

Experimental Protocols & Research Methodologies

For researchers investigating this association, several well-established methodologies are central to the field.

Core Epidemiological Study Designs

- Cross-Sectional Analysis: Used to determine the prevalence of T2DM/MetS in pre- vs. post-menopausal women or to compare the mean age at menopause in women with and without T2DM at a single point in time [15] [16].

- Key Protocol: Recruit defined cohorts (e.g., premenopausal, perimenopausal, postmenopausal). Confirm menopausal status via 12 months of amenorrhea (excluding other causes). T2DM status is confirmed via HbA1c ≥6.5%, physician diagnosis, or glucose tolerance tests. Data analysis employs multivariable regression to adjust for confounders like age, BMI, and smoking [15] [16].

- Prospective Cohort Studies: Ideal for establishing temporal sequence and calculating hazard ratios (HR). These studies follow premenopausal women over time to observe the onset of menopause and subsequent development of T2DM [14].

- Meta-Analysis: The gold standard for synthesizing evidence. A rigorous protocol (e.g., PRISMA) is followed, including a systematic search of multiple databases, quality assessment of studies (e.g., Newcastle-Ottawa Scale), and pooled analysis of effect sizes (Odds Ratios, Hazard Ratios) using appropriate statistical models [14].

Assessing Metabolic Parameters in Clinical Research

To move beyond epidemiological association and explore mechanisms, precise measures of glucose homeostasis and body composition are essential.

- Glucose Homeostasis:

- Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp: The gold-standard method for directly measuring insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues [3] [12].

- Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IVGTT) with Modeling: Used to assess insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function [12].

- Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR): A simpler, widely used index calculated from fasting glucose and insulin levels. A meta-analysis showed HRT can reduce HOMA-IR by 13% [4] [17].

- Body Composition Analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Assays for Investigating Menopause and Metabolic Disease

| Item / Assay | Specific Function / Example | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA Kits | Quantifying serum 17β-Estradiol, Testosterone, SHBG | Measure endogenous sex hormone levels for correlation with metabolic markers. |

| Metabolic Panel Assays | Enzymatic colorimetric tests for LDL-C, TG, HbA1c (HPLC method) | Determine lipid profiles and glycemic control as defined by ADA criteria [16]. |

| Body Composition Tools | DEXA Scan; CT Scan for VAT measurement | Objectively track changes in visceral fat and lean mass in study cohorts [12]. |

| HRT Formulations | Transdermal 17β-Estradiol; Oral Conjugated Estrogens; Medroxyprogesterone Acetate | Investigate the metabolic effects of different MHT types, routes, and progestogen additions [3] [4]. |

Hormone Therapy: Mechanisms & Research Considerations

Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT) is a critical intervention to study in the context of mitigating diabetes risk post-menopause.

Mechanisms of Action on Glucose Metabolism

MHT, particularly estrogen, improves glycemic control through several mechanisms, as shown in the diagram below.

Evidence from a meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials confirms that MHT (both estrogen-alone and estrogen-plus-progestogen) significantly reduces insulin resistance in healthy postmenopausal women [17]. Furthermore, a recent retrospective cohort study demonstrated that MHT use in perimenopausal individuals with prediabetes led to a sustained decrease in diabetes risk over 20 years (HR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.58–0.83) [18].

Formulation and Timing in Research Design

When designing studies on MHT, the formulation and timing are critical variables.

- Route of Administration: Transdermal estrogen is often preferred in studies involving women with cardiovascular risk factors due to its lower risk of venous thromboembolism compared to oral estrogen [4].

- Timing Hypothesis: The beneficial metabolic effects of MHT are most pronounced when initiated early, within 10 years of menopause or before the age of 60 [4]. Research protocols must carefully account for this window of intervention.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

Q1: How is "early menopause" consistently defined in epidemiological studies? Early menopause is typically defined as the permanent cessation of menstruation between the ages of 40 and 45 years. Menopause before age 40 is classified as premature ovarian insufficiency [15] [14]. Consistent use of these definitions is vital for cohort homogeneity and cross-study comparisons.

Q2: What are the key confounding factors that must be adjusted for in statistical analyses? Robust studies adjust for a range of potential confounders, including:

- Demographics: Age, race, and socioeconomic status.

- Lifestyle Factors: Smoking status, physical activity level, and alcohol use.

- Anthropometrics: Body Mass Index (BMI) and waist circumference.

- Medical History: Parity, use of oral contraceptives, and family history of T2DM [15] [16] [14].

Q3: Does MHT's protective effect against diabetes hold in high-risk populations, such as those with obesity? Stratified analyses suggest that the benefit may vary. One study found that MHT significantly reduced diabetes risk in individuals with a BMI < 30 kg/m², but the effect was not significant in those with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m² [18]. This highlights the need for subgroup analysis in clinical trials.

Q4: What is the relationship between surgical menopause and metabolic risk? Surgical menopause (bilateral oophorectomy) is strongly linked to a higher incidence of MetS and a 57% increased risk of diabetes compared to natural menopause, likely due to the abrupt and severe withdrawal of estrogen [11] [3]. This cohort should be analyzed separately in research studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Estrogen & Metabolic Research

FAQ 1: What is the primary clinical evidence linking estrogen to improved glycemic control? Large, randomized controlled trials and a recent meta-analysis of 17 trials conclusively show that Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT) reduces insulin resistance and delays the onset of type 2 diabetes in women [3] [17]. The protective effect is more pronounced with estrogen-alone therapy compared to estrogen-plus-progestogen regimens [17].

FAQ 2: Which estrogen receptor is primarily responsible for its metabolic benefits? Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is the primary mediator of estrogen's beneficial effects on glucose homeostasis [19] [20]. Studies show that the loss of ERα, but not estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), results in insulin resistance and obesity, while ERα-specific agonists can reverse diet-induced insulin resistance [20].

FAQ 3: How does the route of estrogen administration (oral vs. transdermal) impact its metabolic effects? The meta-analysis indicates that both oral and transdermal hormone therapy significantly reduce insulin resistance in healthy postmenopausal women [17]. The molecular mechanisms affected can vary with the route of administration, which may explain historical discrepancies in study outcomes [3].

FAQ 4: What is the role of the newly identified gene IER3 in estrogen-related diabetes mechanisms? A 2025 bioinformatics study identified IER3 as a significantly downregulated estrogen-related gene in diabetes patients, with a diagnostic AUC of 0.723 [21]. Its expression correlates strongly with immune cell infiltration, suggesting a novel role in the immunoregulatory mechanisms of diabetes, presenting a potential new biomarker and therapeutic target [21].

Experimental Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Results in Assessing Estrogen's Effect on Insulin Sensitivity

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Use of different assessment methods (e.g., HOMA-IR vs. hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp) [3]. | Standardize the lab's internal method. For publication, include a secondary method to allow for cross-study comparisons. |

| Variations in MHT formulations (estrogen type, progestogen addition, administration route) [3]. | Precisely report the formulation, dosage, and route of administration. In animal studies, use controlled-release pellets for consistent hormone levels [19]. |

| Sex disparities in animal models, particularly in knockout models [19]. | Include both male and female animals in the study design and analyze data by sex. For in vivo work, use liver-specific Foxo1 knockout (L-F1KO) models to isolate hepatic mechanisms [19]. |

Issue 2: Investigating the Cell-to-Organism Pathway of Estrogen Action

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Difficulty isolating tissue-specific effects (e.g., central nervous system vs. peripheral tissues) [20]. | Use tissue-specific or cell-specific knockout mouse models (e.g., endothelial cell-specific ERα knockout) [22]. Compare subcutaneous vs. intracerebroventricular E2 delivery [20]. |

| Complexity of the signaling cascade, involving genomic and non-genomic pathways [20]. | Employ specific inhibitors of key pathway nodes (e.g., PI3K, Akt) in primary hepatocyte cultures [19]. Use mutant ERα models that can only signal through non-classical pathways [20]. |

Table 1: Clinical and Pre-clinical Quantitative Findings on Estrogen and Glucose Metabolism

| Finding / Metric | Quantitative Result | Context / Model | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction in Diabetes Incidence | 35%-62% reduction | Postmenopausal women on MHT / HRT [20]. | Large-scale clinical trials [20] |

| Effect on Fasting Glucose (Mice) | ~16-22% reduction | OVX and male mice with E2 implant vs. placebo [19]. | Pre-clinical study [19] |

| Diagnostic Potential of IER3 | AUC: 0.723 | Downregulation of estrogen-related gene IER3 in human DM patients [21]. | Bioinformatics study (2025) [21] |

| Risk Increase from Early Menopause | 32% greater risk | Menopause before age 40 vs. age 50-54 [3]. | EPIC-InterAct study [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Role of Hepatic Foxo1 in Estrogen-Mediated Suppression of Gluconeogenesis

This protocol is adapted from the research that established the critical dependency of E2's glycemic effects on hepatic Foxo1 [19].

1. Animal Model Preparation:

- Ovariectomy (OVX): Perform bilateral ovariectomy on female control (Foxo1L/L) and liver-specific Foxo1 knockout (L-F1KO) mice to induce an estrogen-deficient state.

- Hormone Replacement: At the time of OVX, subcutaneously implant a 60-day sustained-release pellet containing either placebo or 0.05 mg 17β-estradiol (E2).

- Grouping: Include male control and L-F1KO mice with and without E2 implants to investigate sex-specific effects.

2. Metabolic Phenotyping (after 8 weeks of treatment):

- Fasting Blood Glucose: Measure after a 16-hour fast.

- Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT): Administer glucose (e.g., 2 g/kg body weight) intraperitoneally to 16-hour fasted mice. Measure blood glucose at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes.

- Pyruvate Tolerance Test (PTT): Administer sodium pyruvate (e.g., 2 g/kg) to 16-hour fasted mice to assess gluconeogenic flux. Measure blood glucose as in GTT.

- Insulin Tolerance Test (ITT): Administer human regular insulin (e.g., 0.75 U/kg) to 5-hour fasted mice. Measure blood glucose at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes.

- Serum Collection: Collect blood via cardiac puncture after fasting for hormone analysis (insulin, glucagon, E2).

3. In Vitro Validation in Primary Hepatocytes:

- Hepatocyte Isolation: Isolate primary hepatocytes from control and L-F1KO mice using collagenase perfusion.

- Glucose Production Assay: Culture hepatocytes and treat with 100 nmol/L E2. Measure glucose output in HGP buffer containing gluconeogenic substrates (lactate and pyruvate).

- Signaling Pathway Inhibition: Pre-treat cells with specific inhibitors (e.g., for PI3K or Akt) 30 minutes prior to E2 exposure to delineate the pathway.

4. Molecular Analysis:

- Gene Expression: Analyze mRNA levels of gluconeogenic genes (G6pc, Pck1) in liver tissue or hepatocytes using qRT-PCR.

- Protein Analysis: Perform Western blotting on liver lysates to assess phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) and Foxo1 (Ser253), and total protein levels.

Diagram Title: Estrogen Suppresses Hepatic Gluconeogenesis via ERα-PI3K-Akt-Foxo1 Signaling

Protocol 2: Evaluating Endothelial Cell-Mediated Insulin Delivery to Muscle

This protocol is based on the 2023 discovery of estrogen's role in facilitating insulin transport across the endothelium [22].

1. Genetic Model Generation:

- Generate endothelial cell-specific estrogen receptor knockout mice (EC-ERα-KO) using Cre-lox technology.

2. In Vivo Metabolic Characterization:

- Subject EC-ERα-KO and control mice on both standard and high-fat diets to metabolic tests (GTT, ITT) as described in Protocol 1.

- Compare responses between male and female (both intact and OVX) mice to dissect sex-specific and estrogen-dependent effects.

3. In Vitro Insulin Transport Assay:

- Cell Culture: Grow primary endothelial cells or an immortalized endothelial cell line on Transwell permeable supports.

- Estrogen Treatment: Stimulate cells with physiological concentrations of E2 (e.g., 1-10 nM).

- Insulin Transport Measurement: Add insulin to the apical chamber and measure the rate of its appearance in the basolateral chamber using ELISA.

- Genetic Silencing: Use siRNA to knock down candidate genes (e.g., SNX5) to confirm their functional role in the insulin transport process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Estrogen's Metabolic Actions

| Reagent / Model | Function / Application in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Liver-specific Foxo1 KO (L-F1KO) Mouse [19] | Determines the liver-autonomous requirement of Foxo1 in E2-mediated suppression of gluconeogenesis. | Sex-specific responses to E2 are observed; E2 fails to lower glucose in male L-F1KO mice [19]. |

| Endothelial-specific ERα KO Mouse [22] | Isolates the role of vascular estrogen signaling in whole-body glucose disposal and insulin delivery. | Knockout in both sexes demonstrates that endothelial ERα is critical for E2's anti-diabetic action [22]. |

| ERα-specific Agonist (e.g., PPT) [20] | Used to dissect the metabolic functions of ERα separate from ERβ. | In vivo administration increases insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle [20]. |

| SNX5 siRNA [22] | Validates the role of the sorting nexin 5 protein in estrogen-stimulated insulin transcytosis. | Silencing SNX5 in endothelial cells ablates the insulin transport effect of E2, confirming its key role [22]. |

| Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp | The gold-standard method for assessing whole-body insulin sensitivity in vivo. | Can be combined with tissue-specific tracers to quantify glucose uptake into specific organs like muscle [3]. |

Troubleshooting Common Research Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Glycemic Outcomes in Preclinical Models

- Problem: Variable results in glucose tolerance tests following HRT intervention.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Verify Ovariectomy: Confirm complete ovariectomy in animal models; incomplete estrogen depletion causes variable results.

- Control for Fat Distribution: Monitor and report central abdominal fat mass using DXA; HRT-induced changes in fat distribution significantly influence glycemic outcomes [23] [3].

- Standardize Progestogen: Different progestogens blunt estrogen's metabolic benefits to varying degrees. Use consistent, well-defined progestogens like micronized progesterone or dydrogesterone for comparability [24].

Challenge 2: Confounding Effects of Aging versus Estrogen Deficiency

- Problem: Difficulty isolating the effects of estrogen deficiency from chronological aging in metabolic studies.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Utilize Surgical Models: Ovariectomized young animal models allow study of estrogen deficiency independent of advanced aging.

- Apply "Timing Hypothesis": In clinical research, stratify cohorts based on time since menopause (<10 years vs. >10 years). Metabolic benefits are more pronounced with early intervention [3] [24] [25].

Challenge 3: Discrepancies in Insulin Sensitivity Measurements

- Problem: Different methods (e.g., HOMA-IR vs. hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp) yield conflicting results on HRT-induced insulin sensitivity improvement.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Select Appropriate Assays: Understand that HOMA-IR primarily reflects hepatic insulin resistance, while the clamp technique measures peripheral (muscle) insulin sensitivity. Estrogen affects both pathways [3].

- Report Methodology Consistently: Clearly specify the insulin sensitivity assessment method used to enable valid cross-study comparisons [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Experimental Design

Q1: What are the key mechanistic pathways by which HRT impacts lipid metabolism and body composition?

- A: Estrogen, primarily via Estrogen Receptor α (ERα), mediates its effects through multiple pathways:

- Central Nervous System: In the ventromedial hypothalamus, E2-ERα signaling regulates sympathetic nervous system output to adipose tissue, reducing visceral fat accumulation and promoting energy expenditure [3].

- Direct Tissue Effects: In muscle and liver, estrogen enhances insulin receptor expression and signaling, improving insulin sensitivity [24].

- Lipid Metabolism: Estrogen increases fat oxidation and reduces fat storage, counteracting the menopausal shift towards visceral adiposity [3] [24].

Q2: How does the route of estrogen administration influence metabolic and inflammatory outcomes?

- A: The administration route critically impacts the risk profile and some metabolic effects.

- Oral Estrogen: Undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver, leading to a more pronounced improvement in lipid profiles (e.g., significant reduction in total cholesterol) but also increased production of clotting factors and inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) [24].

- Transdermal Estrogen: Avoids first-pass liver metabolism, providing a more favorable safety profile with non-significant risks of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and neutral effects on inflammatory markers. It is preferred for subjects with higher cardiovascular risk [24] [26].

Q3: Which progestogen has the most favorable profile for combination therapy in metabolic research?

- A: The choice of progestogen is critical as it can modulate estrogen's benefits.

- Micronized Progesterone and Dydrogesterone are associated with a non-significant increase in breast cancer risk and have minimal negative impact on insulin resistance and lipid metabolism [24] [26].

- Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) is reported to blunt some of estrogen's beneficial metabolic effects and may be associated with a higher risk profile [23] [26].

Q4: What is the optimal timing for HRT initiation to study metabolic benefits?

- A: The "window of opportunity" hypothesis is crucial. The most consistent metabolic benefits—including improved glycemic control, lipid metabolism, and reduced diabetes incidence—are observed when HRT is initiated in perimenopausal or early postmenopausal women (within 10 years of menopause onset or before age 60) [24] [25] [18]. Initiating therapy late (after age 60 or >10 years post-menopause) in animals or humans with established atherosclerosis may yield neutral or negative outcomes.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Metabolic Effects of 6-Month HRT in Postmenopausal Women with Type 2 Diabetes [23]

| Metabolic Parameter | Change with HRT (Mean ± SD) | Change with Observation (Mean ± SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Abdominal Fat | -175 ± 51 g | -24 ± 56 g | 0.05 |

| Waist-to-Hip Ratio | -0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.009 | 0.007 |

| HbA1c | -0.34 ± 0.24% | 0.6 ± 0.4% | 0.04 |

| Total Cholesterol | -0.6 ± 0.1 mmol/L | 0.2 ± 0.2 mmol/L | 0.001 |

| Resting Energy Expenditure | 33 ± 23 kJ/day | -38 ± 23 kJ/day | 0.04 |

Table 2: Long-Term Diabetes Risk Reduction with MHT in Individuals with Prediabetes [18]

| Cohort Characteristic | Hazard Ratio (HR) for Diabetes Development | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (Aged 46-60) | 0.693 | 0.577, 0.832 |

| By BMI (kg/m²): | ||

| BMI ≤ 24.9 | Significant Risk Reduction | Reported |

| BMI 25 - 29.9 | Significant Risk Reduction | Reported |

| BMI ≥ 30 | No Significant Risk Reduction | Reported |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Body Composition and Fat Distribution via DXA

- Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the impact of HRT on total body fat, lean mass, and central abdominal fat distribution.

- Methodology:

- Subject Preparation: Participants should be fasted and in a voided state to minimize gut and bladder content interference.

- Positioning: Position the subject supine on the DXA scanner table with arms at sides, slightly separated from the body. Use foam supports under the knees and feet for comfort and stability.

- Scanning & Analysis: Perform a total body scan. Use the regional analysis feature to define a region of interest (ROI) for central abdominal fat. A standard ROI is the area between the top of the iliac crest and the bottom of the rib cage. The software automatically calculates fat mass, lean mass, and bone mineral density for the whole body and the defined ROI [23].

- Key Parameters: Central abdominal fat mass (g), total fat mass (kg), lean body mass (kg), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR).

Protocol 2: Evaluating Insulin Sensitivity via Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp

- Objective: To measure peripheral insulin sensitivity accurately.

- Methodology:

- Baseline Period: After an overnight fast, administer a primed, continuous infusion of insulin (e.g., 40 mU/m²/min) to achieve steady-state hyperinsulinemia.

- Glucose Infusion: Simultaneously, initiate a variable-rate infusion of 20% glucose to maintain blood glucose at a predetermined euglycemic level (e.g., 5.0 mmol/L or 90 mg/dL). Blood glucose is measured every 5-10 minutes.

- Steady-State Measurement: The clamp period typically lasts for 120 minutes. The mean glucose infusion rate (GIR) during the final 30 minutes, when steady-state is achieved, represents the whole-body insulin-mediated glucose disposal rate (M-value), expressed in mg/kg/min [3].

- Key Parameters: M-value, steady-state insulin level.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Assays for Investigating HRT's Metabolic Impact

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen Formulations | Conjugated Equine Estrogen (CEE), Micronized 17β-Estradiol | Replenishes estrogen levels; used to compare metabolic effects of different estrogen types [23] [27]. |

| Progestogens | Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA), Micronized Progesterone, Dydrogesterone | Protects endometrium in models with intact uterus; critical for studying how different progestogens modulate estrogen's metabolic benefits [23] [24]. |

| Body Composition Analysis | Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) | Precisely quantifies total fat mass, lean mass, and regional fat distribution (e.g., central abdominal fat) [23] [3]. |

| Glycemic Control Assays | HbA1c, Fasting Glucose, Oral/Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT/IVGTT) | Standard measures for assessing long-term and acute glycemic control [23] [3]. |

| Insulin Sensitivity Assays | Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp, HOMA-IR | Gold-standard and surrogate measures for assessing peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity [3]. |

| Lipid Profile Assays | Total Cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, Triglycerides, ApoB | Evaluates the impact of HRT on lipid metabolism and cardiovascular risk factors [23] [24]. |

| Inflammatory Biomarkers | High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP), TNF-α, IL-6 | Measures systemic inflammation, which is linked to insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease [4]. |

Designing Personalized HRT Regimens: From Patient Stratification to Regimen Selection

This technical support center provides specialized guidance for researchers and drug development professionals working within the complex field of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) optimization for postmenopausal women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). The interplay between cardiovascular (CV), thrombotic, and oncological risks presents significant challenges in designing robust clinical experiments and interpreting their outcomes. The protocols, troubleshooting guides, and FAQs contained herein are designed to address specific methodological issues and enhance the quality and reproducibility of your research. The content is framed within the context of a broader thesis on optimizing HRT regimens, focusing on the critical need for integrated patient risk profiling before and during therapeutic intervention. This resource synthesizes current evidence and established methodologies to support your experimental workflows, from initial patient stratification to the assessment of metabolic and cognitive outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key cardiovascular risk factors to document during patient screening for an HRT study in postmenopausal women with T2DM?

- Answer: A comprehensive baseline cardiovascular (CV) assessment is critical. You should document factors outlined in contemporary cardio-oncology guidelines, as they provide a structured framework for risk stratification that is adaptable to HRT research [28]. These include:

- Previous Cardiovascular Disease (CVD): Heart failure, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, stable angina, severe valvular heart disease, and arterial vascular disease [28].

- Cardiac Imaging Parameters: Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), with particular attention to an LVEF <50% or even a "borderline" LVEF of 50–54% [28].

- Cardiac Biomarkers: Elevated baseline levels of cardiac troponin (cTn) and B-type natriuretic peptides (NPs) [28].

- Age and CV Risk Factors: Age ≥65 years, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidaemia [28].

- Lifestyle Risk Factors: Current smoking and obesity (BMI >30 kg/m²) [28].

FAQ 2: According to recent evidence, what is the recommended timing for HRT initiation in postmenopausal women with T2DM to maximize benefit and minimize risk?

- Answer: Current evidence supports the "timing hypothesis." HRT should be initiated early, ideally within 10 years of menopause onset, to achieve cognitive and metabolic benefits [4]. Starting therapy beyond this window or in older postmenopausal women may increase the risk of thromboembolic events and negative cardiovascular effects [4] [3].

FAQ 3: Which route of estrogen administration is preferred for study participants with T2DM who are at moderate to high cardiovascular risk?

- Answer: Transdermal estrogen is generally preferred over oral estrogen for women with T2DM and elevated CV risk. Evidence indicates that transdermal estrogen has a lower associated risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and a more neutral or potentially beneficial effect on cardiovascular health [4].

FAQ 4: We are observing inconsistent effects of HRT on insulin sensitivity in our preclinical models. What could explain these discrepancies?

- Answer: Discrepancies in insulin sensitivity outcomes can arise from several methodological factors [3]:

- Formulation Differences: The type of estrogen and the addition of specific progestogens (e.g., drospirenone) can significantly influence metabolic outcomes [3] [29].

- Route of Administration: Oral and transdermal estrogen may have different metabolic effects.

- Assessment Method: The choice of insulin sensitivity measurement (e.g., HOMA-IR vs. hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp) can yield different results. The clamp technique is considered the gold standard but is more complex [3].

FAQ 5: How should we assess and stratify the risk of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) in our study cohort?

- Answer: While no single dominant score exists for HRT-specific VTE risk, you should adopt a systematic approach. Integrate known risk factors from the literature, which include a personal or family history of VTE, obesity, and the use of oral (as opposed to transdermal) estrogen formulations [4]. For reference, consult established risk assessment models from related fields, such as the Khorana score or other cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) scores, to ensure a comprehensive assessment [30].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: High Drop-out Rates or Adverse Event Reporting in Clinical Trial Phases.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate pre-screening and risk stratification, leading to the enrollment of participants for whom the HRT regimen is inappropriate.

- Solution:

- Implement the HFA-ICOS risk stratification tool as a structured pre-screening checklist to identify patients at "High" or "Very High" risk for CV toxicity prior to enrollment [28]. This tool effectively categorizes pre-existing conditions.

- Establish a multidisciplinary review team (endocrinologist, cardiologist, gynecologist) to evaluate patient-specific risks before final inclusion [4].

- Clearly define and document exclusion criteria, such as uncontrolled hypertension, significant liver disease, or a history of recent surgery [29].

Problem: Inconsistent Glycemic Control Data in Study Participants.

- Potential Cause: Reliance on a single metric or an inappropriate method for the study population.

- Solution:

- Implement a multi-parameter glycemic assessment protocol. This should include HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and fasting insulinemia to calculate HOMA-IR [29].

- For more detailed physiological insight, consider employing the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp technique in a subset of participants, acknowledging its complexity [3].

- Strictly standardize the timing of blood sample collection in relation to HRT administration and meals.

Problem: Confounding Effects of Concomitant Medications on Primary Endpoints.

- Potential Cause: Failure to account for the metabolic effects of common diabetes medications, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors.

- Solution:

- Document all concomitant medications at baseline and throughout the study.

- Use stratified randomization during trial design to ensure balanced distribution of participants using these drugs across study arms.

- Statistically adjust for the use of these medications as covariates in the final analysis model. Future research should specifically investigate the interplay between HRT and modern diabetes therapies [4].

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

Protocol: Comprehensive Baseline Cardiovascular Risk Stratification

Objective: To systematically identify patients at high risk for cardiovascular toxicity prior to enrollment in an HRT intervention study.

Methodology:

- Medical History & Physical Exam: Conduct a comprehensive review of systems focusing on CV history, thrombotic events, and cancer. Perform a physical exam including BMI and waist circumference [28].

- Diagnostic Tests:

- 12-lead Electrocardiogram (ECG): Assess for arrhythmias and measure QTc interval [28].

- Transthoracic Echocardiogram (TTE): Quantify Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) and assess for structural heart disease [28].

- Blood Biomarkers: Measure fasting lipid profile, renal function (eGFR), cardiac troponin (cTn), and B-type Natriuretic Peptides (NPs) [28].

- Risk Categorization: Utilize the adapted HFA-ICOS risk table (see Table 1) to assign a baseline risk category (Low, Moderate, High, Very High).

Table 1: Adapted HFA-ICOS Baseline CV Risk Stratification for HRT Research [28]

| Risk Factor Category | Specific Risk Factor | Risk Level for HRT Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Previous CVD | Heart Failure / Cardiomyopathy | Very High |

| Myocardial Infarction / Stable Angina | High | |

| Severe Valvular Heart Disease | High | |

| Cardiac Imaging | LVEF <50% | High |

| LVEF 50–54% | Moderate | |

| Cardiac Biomarkers | Elevated Baseline NPs or cTn | Moderate |

| Age & CVRF | Age ≥80 years | High |

| Age 65–79 years | Moderate | |

| Hypertension / Diabetes / Chronic Kidney Disease | Moderate | |

| Lifestyle Factors | Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m²) / Current Smoker | Moderate |

Protocol: Assessing the Impact of HRT on Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR)

Objective: To evaluate the effect of a specific HRT regimen on insulin sensitivity in postmenopausal women with T2DM over a 12-month period.

Methodology (Based on a Prospective Clinical Study) [29]:

- Study Population: Postmenopausal women with T2DM, confirmed by FSH >30 mIU/ml and estradiol <20 pg/mL.

- Intervention: Randomize participants to HRT group (e.g., 1mg 17β-estradiol + 2mg drospirenone orally daily) or non-HRT control group.

- Sample Collection & Analysis:

- Collect blood samples after a 12-hour fast at baseline and 12 months.

- Analyze samples for Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) and Fasting Insulinemia.

- Calculation:

- Calculate the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) using the formula: HOMA-IR = (Fasting Glucose [mmol/L] × Fasting Insulin [µU/mL]) / 22.5

- Statistical Analysis: Compare within-group changes (baseline vs. 12 months) using a paired t-test and between-group differences using an independent samples t-test. A p-value <0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Table 2: Expected Metabolic Outcomes from a 12-Month HRT Intervention [29]

| Metabolic Parameter | HRT Group (Baseline) | HRT Group (12 Months) | Control Group (Baseline) | Control Group (12 Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting Plasma Glucose (mmol/L) | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 6.9 ± 0.6 * | 7.8 ± 1.1 | 8.0 ± 0.9 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 7.1 ± 0.4 * | 7.9 ± 0.5 | 7.9 ± 0.6 |

| Fasting Insulin (µU/mL) | 12.2 ± 3.4 | 10.1 ± 2.8 * | 12.3 ± 3.2 | 12.5 ± 3.5 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.23 ± 1.7 | 3.11 ± 1.2 * | 4.31 ± 1.8 | 4.45 ± 1.9 |

*Statistically significant change from baseline (p < 0.001).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for HRT Mechanistic and Clinical Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| 17β-Estradiol | The primary estrogen used in HRT formulations for research; allows study of estrogen's direct metabolic effects [29]. | Pharmaceutical grade; specify oral or transdermal delivery system. |

| Drospirenone | A progestogen often combined with estradiol; has anti-mineralocorticoid activity which may be beneficial in metabolic syndrome [29]. | Pharmaceutical grade; used in combination therapy. |

| ELISA Kits (Insulin, cTn, NPs) | For quantitative measurement of key biomarkers in serum/plasma to assess insulin resistance and cardiovascular strain [29] [28]. | High-sensitivity, validated kits for clinical research. |

| HOMA2 Calculator | Software tool for calculating HOMA2 indices (%B, %S, IR) from fasting glucose and insulin, providing a more refined estimate than the classic HOMA-IR [29]. | Available from the University of Oxford. |

| Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp Setup | The gold-standard method for directly measuring whole-body insulin sensitivity in a subset of participants for deep phenotyping [3]. | Requires controlled infusion pumps and frequent glucose monitoring. |

| Structured Clinical Interview Protocol | Standardized tool for consistent and comprehensive assessment of menopausal symptoms, medication history, and adverse events across the study cohort. | Based on Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) or similar. |

Visualizations: Pathways and Workflows

Integrated Risk Assessment Workflow

HRT & Insulin Sensitivity Signaling Pathway

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting HRT Regimens for Research in Type 2 Diabetes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the transdermal route of estrogen administration recommended over oral for HRT regimens in women with type 2 diabetes?

The key difference lies in the metabolic pathway and associated thromboembolic risk. Oral estrogen undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver, which can impair the balance between clotting and anti-clotting proteins and increase the production of triglycerides [31]. Transdermal estrogen bypasses this first-pass effect, entering the circulation directly through the skin, and is associated with a significantly lower risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) [32] [33]. For women with type 2 diabetes, who already have an elevated baseline cardiovascular risk, this safety profile is crucial. A 2025 real-world study found that oral estrogen doubled the risk of pulmonary embolism and increased heart disease risk by 21% compared to transdermal formulations in this population [31].

FAQ 2: What is the evidence supporting micronized progesterone as the optimal progestogen in HRT, especially for women with type 2 diabetes?

Micronized progesterone, a body-identical hormone, is preferred over synthetic progestogens due to its superior safety profile, particularly regarding breast cancer risk and metabolic impact [33]. Evidence suggests that for the first 5 years of use, estrogen combined with micronized progesterone is not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer [33]. Furthermore, its metabolic profile is more neutral. This is critical for women with type 2 diabetes, as some synthetic progestogens can worsen insulin resistance. Micronized progesterone is not associated with the diabetogenic effect that has been observed with other progestogen formulations, such as 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate [34] [35].

FAQ 3: How does the timing of HRT initiation relative to menopause affect metabolic outcomes in research populations?

The "timing hypothesis" or "window of opportunity" suggests that initiating HRT early in menopause (within 10 years of onset or before age 60) provides the most benefit for metabolic parameters and cardiovascular risk reduction [4] [36] [3]. Early initiation is linked to improved insulin sensitivity, preserved pancreatic beta-cell function, and a lower incidence of type 2 diabetes [4] [3]. Starting HRT beyond this window, particularly in older women with established vascular disease, may be associated with increased risks [4].

FAQ 4: What are the critical methodological considerations when designing studies to compare HRT formulation effects on glucose homeostasis?

Discrepancies in study outcomes often stem from the methods used to assess glucose metabolism [3]. Researchers should note that clinical indices like HOMA-IR may show different results compared to steady-state methods like the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (the gold standard for measuring insulin sensitivity) [3]. Consistency in assessment tools is vital for valid comparisons. Furthermore, study design must account for key confounders in women with type 2 diabetes, including age, time since menopause, BMI, HbA1c levels, and history of hypertension, to isolate the effect of the HRT formulation [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Findings on HRT's Impact on Lipid Profiles

- Potential Cause: The route of estrogen administration significantly influences lipid metabolism. Oral estrogens consistently increase triglycerides, which can be a concern in diabetic dyslipidemia, while transdermal estrogens have a more neutral effect [37].

- Solution: When designing protocols or interpreting data, explicitly stratify outcomes by administration route. The table below summarizes typical lipid profile changes to guide expected outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Effects of HRT Formulations on Metabolic Parameters

| Parameter | Oral Estrogen | Transdermal Estrogen | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| VTE Risk | Significantly Increased [32] [31] | Neutral/Safer Profile [32] [33] [31] | Strongest differentiating factor. |

| Triglycerides | Increases (e.g., +20.7% with CEE) [37] | Neutral effect [37] | Critical for patients with hypertriglyceridemia. |

| HDL Cholesterol | Increases (e.g., +9.0% with CEE) [37] | Neutral effect [37] | The clinical benefit of this increase is debated. |

| Glycemic Control | Improves insulin sensitivity [4] [3] | Improves insulin sensitivity [4] [3] | Both routes show benefit vs. no HRT. |

| Breast Cancer Risk (with Progestogen) | Small increased risk with synthetic progestogens [33] | No increased risk for first 5 years with micronized progesterone [33] | Progestogen type is a key variable. |

Problem: Patient Selection Bias in Observational Studies

- Potential Cause: Women prescribed transdermal HRT are often those with higher baseline cardiovascular risk (e.g., obesity, diabetes), creating a "channeling bias" where higher-risk patients are directed to the supposedly safer therapy [31].

- Solution: In data analysis, employ rigorous statistical methods like propensity score matching to control for confounders such as age, BMI, HbA1c, and hypertension history [31]. This allows for a more valid comparison between treatment groups.

Problem: Concerns About Progestogen's Impact on Glucose Tolerance

- Potential Cause: The use of certain synthetic progestogens, which have been linked to an increased risk of gestational diabetes and may worsen insulin resistance [34].

- Solution: Standardize the use of body-identical micronized progesterone in research protocols where possible. Evidence suggests vaginal micronized progesterone is not associated with a higher risk of gestational diabetes, supporting its metabolically neutral profile [35].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing the Impact of HRT Route on Glucose Metabolism in a Rodent Model of Type 2 Diabetes

This protocol is designed to isolate the effect of estrogen administration route on glucose homeostasis, independent of progestogen.

- Animal Model: Use ovariectomized female mice or rats fed a high-fat diet to model postmenopausal type 2 diabetes.

- Study Groups:

- Group 1: Control (vehicle)

- Group 2: Oral 17β-estradiol (administered via drinking water or gavage)

- Group 3: Transdermal 17β-estradiol (administered via slow-release subcutaneous pellet)

- Ensure doses are physiologically comparable.

- Duration: 8-12 weeks of treatment.

- Endpoint Measurements:

- Insulin Sensitivity: Perform an insulin tolerance test (ITT).

- Glucose Tolerance: Perform an intraperitoneal or oral glucose tolerance test (GTT).

- Tissue Analysis: Collect tissues for:

- Liver: Analyze gene expression of gluconeogenic enzymes (PEPCK, G6Pase).

- Skeletal Muscle and Adipose Tissue: Assess insulin signaling pathway activation (e.g., via Western blot for p-AKT/AKT) in response to insulin stimulation.

- Body Composition: Monitor changes in visceral adiposity using MRI or by weighing fat pads at sacrifice.

The diagram below illustrates the key metabolic pathways and tissue-specific effects of estrogen that this protocol aims to investigate.

Protocol 2: Clinical Research Methodology for Comparing HRT Formulations

This outlines a robust clinical study design based on recent high-quality research [31].

- Study Design: Retrospective cohort or prospective observational study using electronic health records.

- Population: Identify postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes initiating HRT. Key inclusion criteria: age 45-60, confirmed T2D diagnosis.

- Exposure Groups:

- Cohort A: Transdermal estrogen (patch/gel) + micronized progesterone.

- Cohort B: Oral estrogen + micronized progesterone.

- Control Cohort: Age-matched women with T2D not using HRT.

- Matching: Use propensity score matching (1:1) to control for age, ethnicity, BMI, HbA1c, hypertension, and diabetes duration.

- Follow-up: Minimum 5 years.

- Primary Outcomes: Incidence of:

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE: DVT, PE)

- Ischemic heart disease

- Ischemic stroke

- Secondary Outcomes: Incidence of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers; changes in HbA1c and lipid panels.

- Statistical Analysis: Use Cox proportional hazards models to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for outcomes between matched groups.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for HRT Formulation Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Rationale | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 17β-Estradiol (for research) | The primary biologically active estrogen for in vitro and in vivo studies. | Use in cell culture (dissolved in ethanol/DMSO) or animal models (oral gavage, subcutaneous pellets, transdermal patches). |

| Micronized Progesterone | The body-identical progestogen for endometrial protection with a favorable metabolic and breast safety profile. | Available for clinical research. Contrast with synthetic progestogens (e.g., medroxyprogesterone acetate) to highlight differential effects. |

| Transdermal Delivery Systems | To administer estradiol while bypassing first-pass liver metabolism. | Research-grade patches or gels for animal or human studies. Allows direct comparison with oral administration. |

| Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp | The gold-standard method for precisely quantifying whole-body insulin sensitivity. | Critical for high-fidelity metabolic studies beyond simpler tests like HOMA-IR [3]. |

| Propensity Score Matching Software (e.g., R, Stata) | Statistical method to reduce confounding bias in observational studies, creating comparable treatment and control groups. | Essential for analyzing real-world data to approximate the balance of a randomized controlled trial [31]. |

FAQs: Addressing Key Research Questions

1. What is the mechanistic basis for the "Timing Hypothesis" in menopausal hormone therapy (MHT)? The "Timing Hypothesis" proposes that the cardiovascular and metabolic benefits of MHT are dependent on initiation timing relative to menopause. Initiating therapy in women younger than 60 or within 10 years of menopause allows MHT to exert protective effects on the vascular endothelium before advanced atherosclerosis sets in. Starting therapy beyond this window, when vascular aging is more advanced, may negate benefits and increase risks of adverse events [38] [39].

2. How does MHT influence insulin resistance and glycemic control in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes (T2DM)? A 2024 meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials concluded that MHT significantly reduces insulin resistance in healthy postmenopausal women [17]. For women with T2DM, the improvements are even more pronounced, with studies showing a 36% reduction in fasting blood glucose and HOMA-IR (Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance). Estrogen enhances insulin sensitivity by modulating insulin receptor expression, improving pancreatic beta-cell function, and reducing systemic inflammation [4].

3. What are the recommended MHT formulations and routes of administration for women with T2DM and cardiovascular risk factors? Transdermal estrogen (patches, gels) is the preferred route for women with T2DM or elevated cardiovascular risk. Unlike oral estrogen, transdermal administration has a neutral effect on blood pressure and does not increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or stroke, making it a safer option [38] [4] [40]. For women with a uterus, progestogen must be added to prevent endometrial cancer; micronized progesterone or dydrogesterone are preferred progestogens due to their lower impact on breast cancer risk [39].

4. What are the critical experimental considerations when modeling the Timing Hypothesis in preclinical studies? Key considerations include the choice of animal model and the timing of intervention. Non-human primates that experience a natural menopause are genetically closest to humans, but rodents are more practical. Ovariectomy in rodents models surgical menopause, creating rapid, severe estrogen deficiency, which differs from the gradual decline in natural menopause. Studies should be designed to compare early intervention (immediately after ovariectomy) versus late intervention to mirror the human clinical window [3] [41].

Troubleshooting Guides for Experimental Design

Challenge: Translating Animal Model Data to Human Clinical Outcomes

- Problem: Data from ovariectomized rodent models does not fully replicate the human condition of natural menopause, which involves gradual hormonal changes and aging.

- Solution: Consider using aged rodent models or non-human primates that experience natural menopause for more translatable results. When using ovariectomized models, explicitly state this limitation and correlate findings with sub-studies of women with surgical versus natural menopause [3].

- Methodology: Implement a dual-model approach:

- Ovariectomy Model: For studying rapid estrogen depletion and the effects of immediate MHT initiation.

- Aged Model: For studying the interaction between hormonal decline and chronological aging, and the effects of late MHT initiation.

Challenge: Discrepancies in Assessing MHT's Effect on Glucose Homeostasis

- Problem: Different methods for assessing insulin sensitivity (e.g., HOMA-IR vs. hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp) can yield conflicting results on the metabolic benefits of MHT [3].

- Solution: Utilize multiple complementary methods within the same study to provide a comprehensive picture.

- Standardized Protocol:

- Primary Measure: Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (the gold standard for measuring whole-body insulin sensitivity).

- Secondary Measures: HOMA-IR (for basal insulin resistance) and Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IVGTT) with minimal model analysis (to assess beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity).

- Additional Biomarkers: Measure glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting glucose, and inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) [4] [3].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Metabolic and Clinical Outcomes of MHT Based on Timing and Formulation

| Outcome Measure | Effect of Early MHT Initiation ( | Effect of Late MHT Initiation | Influence of Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Resistance | ~30% reduction in T2DM incidence; 13% reduction in HOMA-IR in non-diabetic women [4] [17] | Limited to no benefit; potential for harm in older women with established vascular disease [38] [42] | Estrogen-alone therapy shows more prominent reduction than combined therapy [17] |

| Cardiovascular Risk | Cardiovascular protection; significant reduction in stroke risk observed in some cohorts [38] [4] [42] | Small increase in stroke risk (~4.9%); no cardiovascular benefit [38] [42] | Transdermal estrogen has neutral/beneficial effect; oral estrogen may increase VTE and stroke risk [38] [40] |

| Breast Cancer Risk | Lower odds of breast cancer when started in perimenopause [42] [39] | Risk increases with longer duration of use and older age [40] | Progestogen component is decisive; progesterone/dydrogesterone have lower risk than synthetic progestins [39] |

| Bone Mineral Density | Prevents post-menopausal bone loss and reduces fracture risk [40] [41] | Effective at preventing bone loss, but risk-benefit profile less favorable [38] | All systemic MHT formulations are effective [41] |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Investigating MHT in Metabolic Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Models | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 17β-Estradiol (E2) | The primary physiological estrogen; used to investigate mechanisms of estrogen receptor activation on glucose homeostasis and energy expenditure [3]. | Administered via subcutaneous pellet, oral gavage, or in drinking water to ovariectomized rodents. Dosing must be calibrated to achieve physiological, not supraphysiological, levels. |

| Conjugated Equine Estrogens (CEE) | A complex mixture of estrogens derived from pregnant mares' urine; used to model the formulation tested in the WHI trial [3] [39]. | Useful for translational studies comparing the effects of specific estradiol formulations versus the complex mixture used in major clinical trials. |

| Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) | A synthetic progestogen; used to study the impact of progestogens on estrogen's beneficial effects, particularly on breast cancer risk [39]. | Often used in combination with CEE in rodent models to replicate the WHI combined therapy arm. Associated with more negative metabolic and breast tissue effects. |

| Progesterone / Dydrogesterone | Natural progesterone or its isomer; considered a "body-identical" progestogen with a safer risk profile, particularly for breast tissue [39]. | The preferred progestogen for combination therapy in experimental models aiming to mimic modern, optimized clinical practice. |

| Transdermal Estradiol Patches/Gels | Enables non-oral delivery of estradiol, bypassing first-pass liver metabolism [38] [4]. | Used in clinical-style experiments in animal models or human studies to investigate the route-of-administration-dependent effects on clotting factors, lipids, and inflammatory markers. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Timing Hypothesis in an Ovariectomized Rodent Model of T2DM

Objective: To evaluate the metabolic effects of initiating MHT early versus late after estrogen depletion in a diabetic context.

Materials:

- Animal Model: Adult female Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) rats or similar T2DM model.

- Reagents: 17β-Estradiol pellets (for slow-release), progesterone or MPA for injection, vehicle control.

- Equipment: Equipment for hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, metabolic cages, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanner.

Methodology:

- Baseline Phase: At 12 weeks of age, perform baseline measurements of body weight, fasting glucose, and body composition via DEXA.

- Ovariectomy (OVX): Perform OVX or sham surgery on all animals.

- Intervention Groups:

- Group 1 (Early MHT): Initiate MHT (e.g., E2 pellet + progesterone injections) immediately post-OVX.

- Group 2 (Late MHT): Initiate identical MHT regimen 8 weeks post-OVX, after metabolic dysfunction is established.

- Group 3 (OVX Control): Receive vehicle treatment post-OVX.

- Group 4 (Sham Control): Undergo sham surgery and receive vehicle.

- Outcome Measures: At the end of the study period (e.g., 20 weeks of age), conduct:

- Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp to measure insulin sensitivity.

- IVGTT to assess beta-cell function.

- Body composition analysis (DEXA) to quantify fat and lean mass distribution.

- Tissue collection for molecular analysis (e.g., insulin signaling pathway proteins in muscle and liver, hypothalamic neuropeptides).

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of MHT Formulations on Metabolic and Bone Parameters

Objective: To compare the effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen, combined with different progestogens, on glycemic control and bone quality.

Materials:

- Animal Model: Ovariectomized non-human primates or aged mice.

- Reagents: Oral estradiol, transdermal estradiol patches, Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA), micronized progesterone.

- Analytical Equipment: Raman microspectrometer, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for hormone level verification.

Methodology:

- Group Allocation: Ovariectomized animals are randomized into several groups:

- Oral Estradiol + MPA

- Oral Estradiol + Progesterone

- Transdermal Estradiol + MPA

- Transdermal Estradiol + Progesterone

- Vehicle Control

- Treatment Duration: Administer treatments for a period relevant to the model (e.g., 2 years in primates, 3 months in mice).

- Metabolic Phenotyping: Periodically measure body weight, food intake, glucose tolerance, and fasting insulin.

- Bone Quality Analysis: Post-sacrifice, collect iliac crest or femoral bone biopsies.

- Analyze using Raman microspectroscopy to determine bone compositional properties at the ultrastructural level, including mineral/matrix ratio, mineral maturity, and collagen cross-links at precisely defined tissue ages [41].

- Data Integration: Correlate metabolic outcomes (e.g., HOMA-IR) with bone quality parameters to understand systemic versus tissue-specific effects of different MHT regimens.

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Estrogen Signaling in Glucose Metabolism

Experimental Workflow for Timing Hypothesis

FAQs: HRT Dosing in Type 2 Diabetes Research

FAQ 1: What are the key considerations for selecting an HRT formulation in women with T2DM? The primary considerations are the route of administration and the type of progestogen. For women with T2DM, who have an elevated baseline cardiovascular risk, a transdermal estrogen patch is strongly preferred over oral estrogen. Evidence shows that compared to transdermal delivery, oral estrogen doubles the risk of pulmonary embolism and is associated with a 21% increased risk of heart disease in this population [31] [43]. For the progestogen component, selections with neutral effects on glucose metabolism, such as natural progesterone, dydrogesterone, or transdermal norethisterone, are recommended to avoid exacerbating insulin resistance [44].

FAQ 2: What defines "low-dose" and "short-duration" therapy in clinical protocols? "Low-dose" therapy utilizes the minimum effective dose to manage vasomotor symptoms. In practice, low-dose transdermal estrogen patches (e.g., delivering 0.014 to 0.025 mg/day) achieve this goal while minimizing risks [45]. "Short-duration" typically means treatment for less than five years, which aligns with safety data showing a favorable risk-benefit profile within this window for women with T2DM [31] [4]. Treatment should be re-assessed annually to determine if ongoing therapy is warranted.

FAQ 3: What metabolic parameters should be monitored during HRT trials in T2DM subjects? A core set of parameters should be tracked to assess efficacy and safety. Glycemic control should be evaluated via HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and HOMA-IR calculations [4] [44]. Lipid profiles (LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides) and markers of coagulation and inflammation should also be monitored [46]. Regular assessment of body composition (e.g., waist circumference, visceral fat) is valuable, as menopause and T2DM both predispose to adverse changes in fat distribution [3].

FAQ 4: How does the "timing hypothesis" influence study design for HRT in T2DM? The "timing hypothesis" posits that the cardiovascular benefits of HRT are greatest when initiated in younger women (aged <60 years or within 10 years of menopause onset) versus later [4] [44]. This has critical implications for study design. Clinical trials should stratify participants based on time since menopause rather than chronological age alone. Protocols must clearly define and document the menopausal age of participants to ensure valid analysis of cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes [3] [45].