Optimizing Hormone Measurement in Exercise Research: Protocols for Accuracy, Standardization, and Biological Interpretation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing hormone measurement protocols in exercise science, addressing the unique challenges posed by physical activity interventions.

Optimizing Hormone Measurement in Exercise Research: Protocols for Accuracy, Standardization, and Biological Interpretation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing hormone measurement protocols in exercise science, addressing the unique challenges posed by physical activity interventions. It covers the foundational principles of exercise-induced hormonal responses, details methodological best practices for sample collection and analysis, outlines strategies for troubleshooting common pre-analytical and analytical errors, and emphasizes the importance of methodological validation and cross-study comparisons. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current evidence and standards to enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and clinical relevance of hormonal data in exercise research.

Understanding the Exercise-Hormone Axis: Foundational Physiology and Research Imperatives

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Hormone Measurement in Exercise Studies

Q1: Why do my study participants show such variable testosterone responses to the same resistance exercise protocol?

A: Testosterone variability is common and often explained by several modifiable factors. Your data may be influenced by the timing of blood sampling (e.g., during, immediately after, or hours after exercise), as the response is acute and transient [1]. Furthermore, participant characteristics are crucial; studies show that baseline fitness (sedentary vs. resistance-trained), age (young vs. elderly), and body composition (lean vs. obese) significantly modulate the hormonal response [2] [1]. To troubleshoot, ensure you are controlling for and documenting these variables. Consider standardizing the exercise type, as protocols using large muscle mass exercises (e.g., squats) and moderate intensity with higher volume typically elicit more robust responses [1].

Q2: We are measuring cortisol to monitor exercise stress, but our baseline data is inconsistent. What could be the issue?

A: Cortisol has a pronounced circadian rhythm, with peaks in the morning and a decline throughout the day [3]. Inconsistent baselines likely stem from sampling at different times of day. To resolve this, always collect samples at a standardized time for each participant. Furthermore, the method of collection can be a stressor itself; venipuncture can elevate cortisol, whereas saliva collection is a non-invasive alternative that provides a good correlate for serum free cortisol and minimizes pre-analytical stress [3] [4]. Automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) systems have been validated for salivary cortisol and are excellent for processing large sample volumes from continuous monitoring studies [3].

Q3: Our 12-month moderate-intensity exercise intervention found no significant change in resting prolactin levels. Is this expected?

A: Yes, this is an expected and scientifically supported finding. A 12-month randomized controlled trial in women found that a moderate-intensity exercise intervention did not alter serum prolactin concentrations at the 3- or 12-month marks compared to a control group [5]. It is important to distinguish between acute and chronic effects. While acute, intensive exercise bouts can cause immediate spikes in prolactin, these levels typically return to baseline within 24 hours [5] [6]. Long-term exercise training does not appear to shift the baseline resting concentration of this hormone [5].

Q4: How can we better capture the biological activity of the GH-IGF-1 axis in our exercise studies?

A: Measuring only total immunoreactive IGF-I in serum may be insufficient, as exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy is thought to be mediated more by local (paracrine/autocrine) IGF-I than endocrine (circulating) IGF-I [7]. To gain deeper insight, consider implementing molecular weight fractionation techniques, such as High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), to separate different GH and IGF-I isoforms [8]. Research shows these isoforms have different biological activities and respond to exercise in a sex-dependent manner [8]. Additionally, newer assays for free or bioactive IGF-I may provide a more physiologically relevant picture than traditional total IGF-I assays [7].

Quantitative Hormone Responses to Exercise

The following tables summarize key hormonal responses to different exercise stimuli, based on current literature.

Table 1: Acute Hormonal Responses to a Single Bout of Exercise

| Hormone | Exercise Stimulus | Direction of Change | Key Modulating Factors | Temporal Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | Resistance Exercise (High intensity, 6-10 RM, short rest) [2] [1] | Increase ↑ | Muscle mass engaged, training status, age, body fat % [1] | Peaks during/immediately post-exercise; returns to baseline within ~90 min [1] |

| Cortisol | Prolonged Endurance (>60 min); High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) [2] [3] | Increase ↑ | Exercise intensity, duration, time of day, fitness level [2] [3] | Rises during exercise; peaks post-exercise; recovery rate indicates stress load [3] |

| Growth Hormone (GH) | Resistance Exercise; HIIT [8] [7] | Increase ↑ | Intensity, lactate production, fitness level [7] | Rapid increase within ~15 min of onset; peaks post-exercise; sex-dependent isoform responses [8] [7] |

| IGF-1 | Resistance Exercise [8] [7] | Complex (Isoform-specific) | Assay type (total vs. free vs. bioactive); hepatic vs. local production [7] | Systemic total IGF-1 may show minimal change; bioactive and tissue-specific isoforms more relevant [8] [7] |

| Prolactin | High-Intensity Aerobic Exercise [6] | Increase ↑ | Intensity, psychological stress, hyperthermia [6] | Sharp increase immediately post-exercise; returns to baseline within hours [5] [6] |

| Estrogen (Postmenopausal) | Moderate-Intensity Aerobic (45 min, 5 d/wk) [9] | Decrease ↓ (with body fat loss) | Body fat percentage reduction; no effect if body fat is stable [9] | Significant declines observed after 3 months; effect sustained at 12 months with adherence [9] |

Table 2: Chronic Hormonal Adaptations to Long-Term Exercise Training

| Hormone | Adaptation to Chronic Training | Key Context & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | Basal levels may increase or be maintained [2] [1] | More pronounced in individuals with low baseline fitness or who lose body fat [1]. |

| Cortisol | Blunted response to a standardized submaximal workout [2] | Elevated basal cortisol or a chronically low Testosterone/Cortisol ratio can indicate overtraining [2] [4]. |

| IGF-1 | Promotes physiological cardiac hypertrophy via PI3K/Akt & MEK/ERK pathways [10] | Local (paracrine/autocrine) expression in muscle and heart is more critical for adaptation than circulating levels [10] [7]. |

| Prolactin | No significant change in resting concentrations [5] | The acute prolactin response to exercise remains, but the 24-hr circadian rhythm may be augmented on training days [6]. |

| Estrogen | Resting levels reduced in postmenopausal women [9] | The effect is directly linked to a reduction in body fat percentage, as adipose tissue is a primary site of estrogen synthesis after menopause [9]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Acute Resistance Exercise Test (ARET) for GH & IGF-I Isoform Analysis

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating sex-dependent molecular weight isoform responses [8].

- Objective: To perturb the hormonal milieu and analyze the response of GH and IGF-I molecular weight isoforms.

- Subjects: Healthy, non-resistance-trained individuals. A 48-hour refrain from strenuous exercise and a 10-hour overnight fast are required prior to testing.

- Exercise Protocol:

- Exercise: Barbell Back Squat.

- Intensity: 6 sets of 10 repetition maximum (10-RM).

- Rest: 2 minutes of rest between each set.

- The load is adjusted for each set to ensure failure at the 10th repetition with good form.

- Blood Sampling Timeline:

- Pre-exercise (Pre)

- After 3 sets (Mid)

- Immediately post-exercise (Post)

- +15 minutes into recovery (+15)

- +30 minutes into recovery (+30)

- Sample Processing & Analysis:

- Collect blood into serum vacutainers and allow to clot for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 1,500 × g for 20 minutes.

- Aliquot serum and store at -80°C.

- Fractionation: Process serum samples using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with Sephacryl gel filtration columns to separate molecules into distinct molecular weight fractions (e.g., >60 kDa, 30-60 kDa, and <30 kDa) [8].

- Analyze the hormone concentration in each fraction pool using specific immunoassays.

Protocol 2: Assessing Exercise Stress via Salivary Cortisol and the T/C Ratio

This protocol uses a non-invasive method to monitor an athlete's stress response to different training loads [3] [4].

- Objective: To compare the stress response to interval training versus steady-state running using salivary biomarkers.

- Design: A within-subject crossover design over two consecutive days with different exercise intensities.

- Saliva Collection:

- Method: Use Salivette cotton swabs or passive drooling. Participants must not consume food or drink (except water) 15 minutes before collection.

- Timing: Collect samples at standardized times to account for circadian rhythm, for example: upon waking, pre-exercise, post-exercise, and before dinner.

- Storage: Centrifuge samples after collection, and store the supernatant at -20°C until analysis.

- Exercise Sessions:

- Day 1 (High Intensity): Interval training (e.g., 4 sets of 1200-m fast running with 800-m light jogging).

- Day 2 (Lower Intensity): Fixed-speed running for 50 minutes.

- Analysis:

- Measure salivary cortisol and testosterone concentrations using an automated Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA).

- Calculate the Testosterone-to-Cortisol (T/C) ratio.

- Expected Outcome: The rate of change in cortisol will be significantly higher, and the T/C ratio will be significantly lower, after the high-intensity day (Day 1) compared to the lower-intensity day (Day 2), clearly differentiating the physiological stress load [4].

Signaling Pathways in Exercise-Induced Cardiac Adaptation

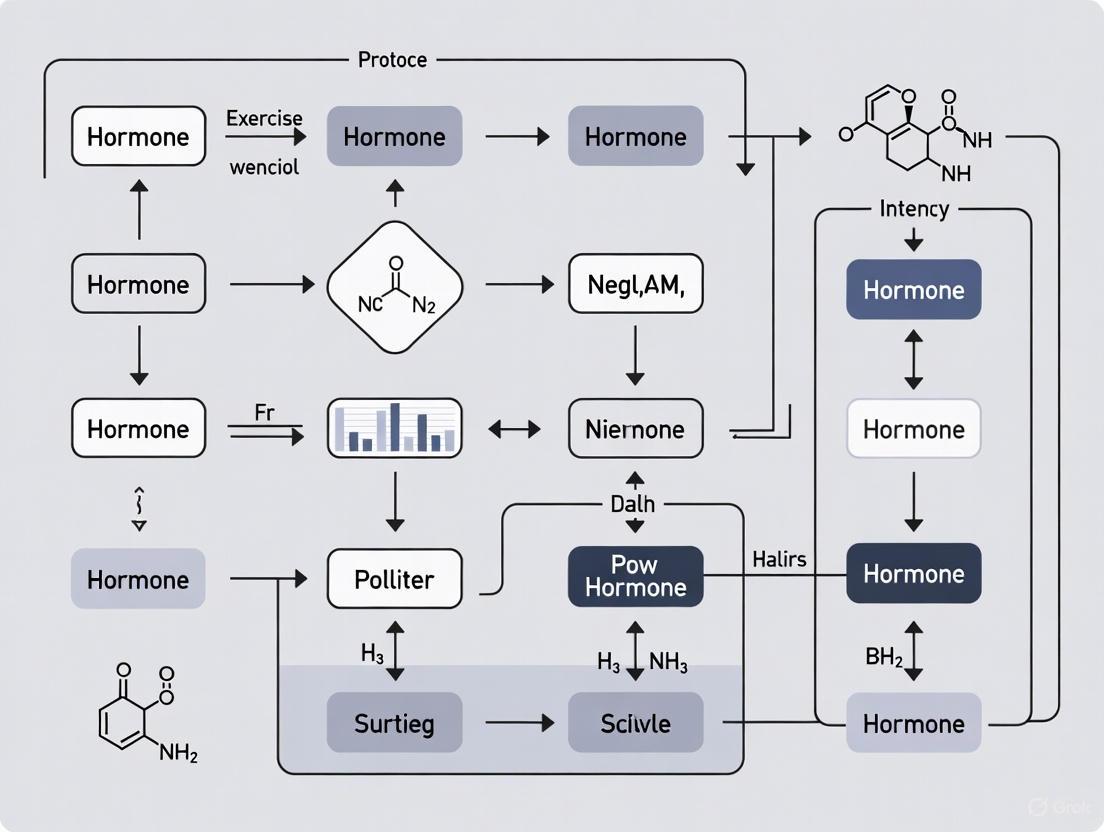

Exercise-regulated hormones activate complex signaling networks that drive physiological cardiac hypertrophy. The diagram below integrates key pathways from the reviewed literature [10].

This diagram illustrates how key hormones released during exercise, including IGF-1, Testosterone, Thyroid Hormones (T3), and Neuregulin-1 (NRG1), bind to their respective receptors and converge on the PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK signaling pathways. The integration of these signals activates the mTORC1/S6K1 pathway, which coordinately drives protein synthesis and physiological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting rigorous exercise endocrinology research, as cited in the studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hormone Measurement

| Item | Function/Application in Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Salivette Cotton Swabs (Sarstedt) | Standardized, non-invasive collection of saliva samples for stress hormone analysis. | Used for sequential saliva sampling in studies monitoring cortisol circadian rhythm in athletes [3]. |

| ECLIA Cortisol/Testosterone Kits (e.g., Roche Elecsys Cortisol II) | Automated, high-throughput measurement of hormone concentrations in serum and saliva. Validated for salivary cortisol [3] [4]. | Used for accurate measurement of a large number of salivary cortisol and testosterone samples; showed strong correlation with serum levels [3] [4]. |

| HPLC System with Sephacryl Gel Filtration Columns | Fractionation of serum into distinct molecular weight pools for analysis of hormone isoforms (e.g., GH and IGF-I variants). | Critical for separating GH and IGF-I into >60 kDa, 30-60 kDa, and <30 kDa fractions to reveal sex-dependent isoform responses to exercise [8]. |

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kits for Prolactin | Quantification of prolactin concentrations in plasma/serum. | Used to profile the 24-hour prolactin response in exercise-trained men, including acute exercise spikes and nocturnal rises [6]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | Traditional, manual method for quantifying specific hormones (e.g., salivary cortisol). | Served as a reference method to validate the accuracy of the newer, automated ECLIA for salivary cortisol measurement [3]. |

Muscular activity is a fundamental component of the "fight or flight" response, activating hormones crucial for maintaining homeostasis during acute exercise [11]. The physiological stress induced by exercise serves as a powerful stimulus for both immediate hormonal secretion and long-term adaptive changes in the endocrine system [12] [13]. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for researchers designing exercise studies and clinicians interpreting hormonal data. The acute hormonal response to exercise is characterized by rapid changes in circulating hormone levels, which are influenced by factors such as exercise modality, intensity, volume, and rest intervals [14] [13]. Conversely, chronic adaptations occur following repeated exercise bouts over time, potentially leading to basal hormonal changes and altered responsiveness of endocrine axes [11]. This technical resource provides evidence-based guidance for optimizing hormone measurement protocols in exercise research, with specific troubleshooting advice for common experimental challenges.

Key Hormonal Pathways and Their Responses

Acute Hormonal Responses to Exercise Stress

The immediate endocrine response to exercise is primarily driven by metabolic and mechanical stressors. Key anabolic and catabolic hormones demonstrate distinct temporal patterns following different exercise protocols.

Figure 1: Signaling pathways activated by different exercise stressors and their hormonal outcomes.

Chronic Hormonal Adaptations to Training

Repeated exercise bouts induce adaptive changes in the endocrine system that support improved performance and recovery. These long-term adaptations represent the body's compensation to persistent training stimuli.

Figure 2: Chronic adaptations of the hormonal system to repeated exercise training.

Experimental Protocols for Hormonal Assessment

Metabolic Stress and Hormonal Response Protocol

This protocol examines the impact of exercise-induced metabolic stress on acute hormonal responses and long-term muscular adaptations [12].

Methodology:

- Participants: 26 male subjects assigned to No-Rest (NR), With-Rest (WR), or Control (CON) groups

- Exercise Protocol: 3-5 sets of 10 repetitions at 10-repetition maximum for lat pulldown, shoulder press, and bilateral knee extension

- NR Regimen: 1-minute interset rest periods

- WR Regimen: 30-second rest at midpoint of each set to reduce metabolic stress

- Blood Collection: Measured lactate, growth hormone (GH), epinephrine (E), and norepinephrine (NE) responses

- Training Duration: 12-week resistance training period

- Outcome Measures: Acute hormonal responses, 1RM, maximal isometric strength, muscular endurance, muscle cross-sectional area

Key Findings: The NR regimen induced significantly stronger lactate, GH, epinephrine, and norepinephrine responses compared to the WR regimen [12]. After 12 weeks, the NR group showed greater increases in all strength measures and significant muscle hypertrophy, while the WR and CON groups did not [12].

Set Volume and Hormonal Response Protocol

This protocol investigates the effects of different set volumes on hormonal responses across various resistance exercise paradigms [14].

Methodology:

- Participants: 11 young men performing multi-joint dynamic exercises

- Protocol Variations:

- Maximum Strength (MS): 5 reps at 88% 1-RM, 3-min rest

- Muscular Hypertrophy (MH): 10 reps at 75% 1-RM, 2-min rest

- Strength Endurance (SE): 15 reps at 60% 1-RM, 1-min rest

- Set Variations: MS and MH protocols with 2, 4, and 6 sets; SE with 2 and 4 sets

- Blood Collection: Before exercise, immediately after, and at 15 and 30 minutes of recovery

- Assayed Hormones: Testosterone, cortisol, growth hormone (hGH)

Key Findings: The number of sets significantly affected cortisol and hGH responses in MH and SE protocols but not in the MS protocol [14]. Testosterone did not change significantly with any workout protocol, suggesting differential sensitivity of various hormonal axes to set volume [14].

Data Synthesis: Hormonal Responses Across Protocols

Table 1: Acute hormonal responses to different resistance exercise protocols

| Exercise Protocol | Testosterone Response | Cortisol Response | Growth Hormone Response | Catecholamine Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Rest Regimen [12] | No significant change | Not reported | Strong increase | Strong epinephrine and norepinephrine increase |

| With-Rest Regimen [12] | No significant change | Not reported | Minimal response | Minimal response |

| Maximum Strength (4 sets) [14] | No significant change | Lower than MH and SE | Lower than MH and SE | Not reported |

| Muscular Hypertrophy (4 sets) [14] | No significant change | Higher than MS | Higher than MS | Not reported |

| Strength Endurance (4 sets) [14] | No significant change | Higher than MS | Highest response | Not reported |

Table 2: Chronic adaptations to 12 weeks of resistance training with different protocols

| Training Outcome | No-Rest Regimen [12] | With-Rest Regimen [12] | Control Group [12] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1RM Improvement | Significant increase (P < 0.01) | Less improvement | No improvement |

| Isometric Strength | Significant increase (P < 0.05) | Less improvement | No improvement |

| Muscular Endurance | Significant increase (P < 0.05) | Less improvement | No improvement |

| Muscle Cross-Sectional Area | Marked increase (P < 0.01) | No significant increase | No significant increase |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research materials for exercise endocrinology studies

| Reagent/Assay | Application in Exercise Endocrinology | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| LH, FSH Assays | Assessment of hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function | Male Hormone Panel (Boston Heart Diagnostics) [2] |

| Comprehensive Hormone Profiling | Multiplexed analysis of steroid hormones and precursors | Comprehensive Hormone Profile (Doctor's Data) [2] |

| Cortisol Assays | HPA axis activation and stress response monitoring | Male Hormones Plus (Genova Diagnostics) [2] |

| IGF-1 Isoform Assays | Detection of muscle-specific IGF-1 variants (e.g., MGF) | Mechano growth factor analysis [13] |

| Catecholamine Analysis | Sympathetic nervous system activation assessment | Epinephrine, norepinephrine measurements [12] |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase | Metabolic stress indicator | Blood lactate analysis [12] |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Hormone Measurement

Q: What could cause undetectable hormonal changes despite appropriate exercise stimulus? A: Consider these potential issues:

- Timing of blood collection: Peak hormonal responses may occur at unexpected timepoints (e.g., IGF-1 peaks 16-28 hours post-exercise) [13]

- Excessive training volume in pre-study habituation may blunt hormonal responsiveness

- Insufficient metabolic stress: Implement shorter rest periods (30-60 seconds) to enhance stimulus [12]

- Inappropriate assay sensitivity: Confirm that your detection method can measure physiological ranges

Q: How can I optimize the detection of anabolic hormonal responses? A: Implement these evidence-based strategies:

- Protocol design: Utilize high-volume, moderate-intensity protocols (8-12 reps at 75% 1RM) with short rest intervals (60 seconds) [14] [13]

- Metabolic stress enhancement: Use "no-rest" regimens with intramuscular rest periods rather than complete recovery [12]

- Set volume: Include 4-6 sets for hypertrophy protocols, as 2 sets may provide insufficient stimulus [14]

- Compound exercises: Prioritize multi-joint movements that recruit large muscle mass

Q: What factors contribute to high inter-subject variability in hormonal responses? A: Key confounding variables include:

- Individual training status: Trained athletes exhibit blunted hormonal responses compared to untrained individuals [11]

- Nutritional status: Ensure standardized pre-testing nutrition, particularly protein and carbohydrate intake [2]

- Age and gender: Hormonal responses differ significantly across demographics [13]

- Circadian rhythms: Standardize testing times to control for diurnal hormonal fluctuations

- Psychological stress: Implement quiet resting periods before baseline blood collection

Q: How should I approach the measurement of cortisol in exercise studies? A: Consider these methodological considerations:

- Response pattern recognition: Cortisol typically shows delayed elevation compared to catecholamines

- Set volume sensitivity: Cortisol responses increase with higher set volumes (4-6 sets) in hypertrophy protocols [14]

- Anabolic-catabolic balance: The testosterone/cortisol ratio may indicate training stress, though its utility as a standalone marker is debated [13]

- Protocol specificity: Strength endurance protocols produce greater cortisol responses than maximum strength protocols [14]

FAQs: Hormonal Responses to Exercise Modalities

Q1: How does high-intensity interval training (HIIT) acutely affect cortisol and testosterone levels? HIIT can create a nuanced hormonal response. It has been identified as a potential stimulator of testosterone levels, with one study suggesting it may help manage the cortisol response during intense training periods [2]. However, the interplay is complex; the stress of high-intensity exercise can elevate cortisol, and the net effect depends on training volume, recovery, and individual fitness levels.

Q2: Why is resistance training particularly effective for stimulating testosterone secretion? Resistance training is a potent stimulator of testosterone release, especially following high-intensity sessions [2]. This acute increase is anabolic, playing a crucial role in the desired adaptations for muscle growth and strength gains. The hormonal response varies with exercise intensity, duration, and the individual's age [2].

Q3: What role does aerobic exercise play in long-term hormonal regulation? Regular aerobic exercise plays a significant role in cortisol regulation [2]. By helping to maintain healthy cortisol levels, it contributes to stress reduction and improved metabolic health. Furthermore, aerobic training enhances insulin sensitivity, supporting the body's efficiency in using insulin for blood glucose management [2].

Q4: What are common factors that lead to inaccurate hormone measurements in exercise studies? Inaccurate measurements can stem from several factors:

- Timing of Sample Collection: Hormone levels fluctuate acutely after exercise [2]. Delayed or mistimed sampling can miss peak concentrations.

- Individual Variability: Characteristics like age, fitness level, and baseline health cause wide variations in hormonal responses [2].

- Insufficient Sample Preparation: In techniques like Western blotting, inadequate blocking or antibody optimization can cause high background noise, obscuring results [15] [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Background Staining in Western Blot Analysis of Hormonal Proteins

Problem: High background noise obscures protein bands during chromogenic detection of hormones (e.g., insulin-like growth factors) or their receptors.

- Solution A: Optimize Blocking and Washes: Ensure the membrane is thoroughly blocked with a high-quality blocking agent to prevent non-specific antibody binding. Implement more rigorous washing steps after each antibody incubation [15].

- Solution B: Titrate Antibodies: High antibody concentrations are a common cause of background. Optimize the dilution of your primary and secondary antibodies to find the concentration that provides a clear signal with minimal noise [15].

- Solution C: Check Membrane Choice: The type of membrane can impact background. Nitrocellulose membranes are often valued for their lower background noise compared to other types [15].

Issue 2: Weak or No Signal in Hormone Detection Assays

Problem: The signal for the target hormone is faint or absent, making quantification difficult.

- Solution A: Verify Antigen Integrity: Ensure that the protein extraction and gel electrophoresis process has not degraded the hormone or receptor of interest. Use fresh protease inhibitors and avoid over-boiling samples.

- Solution B: Use Signal Enhancers: Consider using a membrane treatment reagent, which can increase signal intensity and sensitivity by 3- to 10-fold compared to standard detection methods [17].

- Solution C: Select an Appropriate Substrate: For low-abundance hormones, a high-sensitivity chromogenic substrate is required. Refer to the table in Section 4 for substrate sensitivities [17].

Issue 3: Inconsistent Hormonal Responses in a Subject Cohort

Problem: Study participants show high variability in hormonal responses (e.g., testosterone or cortisol) to the same exercise protocol.

- Solution A: Standardize Pre-test Conditions: Control for factors that significantly impact hormone levels, including time of day, pre-test nutrition, sleep quality, and prior physical activity.

- Solution B: Implement a Familiarization Session: Reduce the impact of novel exercise stress by having subjects perform the protocol once before actual data collection.

- Solution C: Monitor for Overtraining: Persistent fatigue, mood swings, and decreased performance can indicate hormonal imbalances from excessive training load. Adjust exercise regimens and ensure adequate recovery [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Hormonal Responses to Different Exercise Modalities

This table summarizes the typical acute hormonal responses to various exercise modalities, based on current research [2].

| Exercise Modality | Testosterone | Cortisol | Insulin Sensitivity | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance Training | Acute increase, particularly after high-intensity sessions [2]. | Can increase acutely, dependent on intensity. | Improves insulin sensitivity, supporting metabolic health [2]. | Anabolic stimulation; muscle protein synthesis. |

| HIIT | Potential increase, while managing cortisol response [2]. | Managed response during intense training [2]. | Optimizes release, contributing to improved insulin sensitivity [2]. | Efficient stimulation of growth hormone and metabolic pathways. |

| Aerobic Exercise | Varies; prolonged sessions may initially lower, then rebound. | Helps regulate and maintain healthy levels with regular training [2]. | Significant enhancements in insulin sensitivity post-activity [2]. | Metabolic health support; stress system regulation. |

Table 2: Recommended Chromogenic Substrates for Hormone Detection

This table lists common chromogenic substrates used in Western blotting to detect hormones and their receptors, with key specifications to guide selection [15] [16] [17].

| Substrate | Enzyme | Precipitate Color | Approx. Detection Limit | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAB | HRP | Brown/Black | 17 pg (enhanced) | General use; can be enhanced with metals for sensitivity [17]. |

| TMB | HRP | Dark Blue | 20 pg | Applications requiring a high signal-to-noise ratio [17]. |

| 4-CN | HRP | Blue-Purple | 5 ng | Double-staining applications; distinct color [17]. |

| BCIP/NBT | AP | Black-Purple | 30 pg | High sensitivity; sharp band resolution [17]. |

Protocol: Optimized Western Blot for Exercise-Induced Hormonal Proteins

Goal: To reliably detect and semi-quantify changes in hormonal proteins (e.g., IGF-1 Receptor) in muscle tissue biopsies following an exercise intervention.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize muscle tissue in a suitable lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Quantify protein concentration to ensure equal loading.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load 20-40 µg of protein per lane onto a polyacrylamide gel and separate via SDS-PAGE [15].

- Protein Transfer: Transfer proteins from the gel onto a PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane. PVDF is preferred for its higher protein binding capacity and reprobing potential [15].

- Blocking: Incubate the membrane with a blocking buffer (e.g., 5% BSA or non-fat dry milk) for 1 hour at room temperature to prevent nonspecific binding [15].

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate the membrane with a primary antibody specific to your target hormone/receptor (e.g., anti-IGF-1R) diluted in an antibody diluent or blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Optimal dilution must be determined empirically but often starts at 1:500-1:1,000 [17].

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Wash the membrane and incubate with an HRP- or AP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Dilutions typically range from 1:5,000 to 1:50,000 [17].

- Signal Development: Add the chosen chromogenic substrate (e.g., DAB or BCIP/NBT) and develop until bands reach the desired intensity. Stop the reaction by washing with deionized water [15] [16].

- Imaging and Analysis: Capture an image of the membrane. The colored bands can be analyzed with densitometry software for semi-quantification.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Hormone Analysis |

|---|---|

| PVDF Membrane | A membrane with high protein binding capacity and chemical stability, ideal for reprobing with multiple antibodies [15]. |

| HRP-Conjugated Antibodies | Secondary antibodies conjugated to Horseradish Peroxidase; used with chromogenic substrates like DAB and TMB for signal generation [16]. |

| Chromogenic Substrates (DAB, TMB, BCIP/NBT) | Compounds that produce a visible, insoluble colored precipitate upon reaction with an enzyme (HRP or AP), allowing for protein visualization without specialized equipment [15] [16]. |

| SuperSignal Western Blot Enhancer | A membrane treatment reagent that can increase signal intensity and sensitivity by 3- to 10-fold for both chromogenic and chemiluminescent detection [17]. |

| Male Hormone Panel (e.g., Boston Heart Diagnostics) | A comprehensive test used in functional medicine to track key hormone levels like testosterone and cortisol, providing insights for adjusting exercise plans [2]. |

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

IGF-1 PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway

Hormone Detection Workflow

Testosterone Signaling in Muscle

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Hormone Measurement in Exercise Research

Q1: My study on exercise and luteinizing hormone (LH) shows inconsistent results. Could a confounding factor be at play? Yes, energy availability is a potent confounder. LH pulsatility is disrupted when energy availability (dietary energy intake minus exercise energy expenditure) falls below a specific threshold of 30 kcal/kg of Lean Body Mass (LBM) per day [18]. Above this threshold, LH pulsatility typically remains normal. Below it, LH pulse frequency decreases, and amplitude increases, which can affect reproductive function measurements [18]. To troubleshoot, calculate and monitor participants' energy availability throughout your study.

Q2: We see high variability in cortisol responses to identical exercise sessions. What should we control for? The time of day is a major confounding variable for cortisol [19]. The cortisol response to exercise is significantly modulated by circadian rhythms:

- The magnitude of the exercise-induced cortisol increase is greatest when exercise is performed at 2400 h (midnight) [19].

- The response is more pronounced at 0700 h (morning) than at 1900 h (evening) [19].

- Baseline cortisol levels are also significantly higher at 0700 h than at other times [19]. Standardize your exercise testing times and report the time of day for all measurements to control for this confounder.

Q3: How do the menstrual cycle and time of day interact to confound performance and hormone data in female athletes? These factors can have interactive effects. In elite female athletes, physical performance (like jump height and agility) is consistently higher in the afternoon than in the morning across all menstrual phases [20]. However, the luteal phase may be associated with greater mood disturbances and fatigue, especially in the morning and after competition [20]. This interaction can confound measures of psychological response and performance. Your protocol should track both the menstrual cycle phase and time of day to isolate these effects.

Q4: What are the practical methods to control for confounding factors in my study design? You can control confounders during design and analysis [21] [22]:

- Randomization: Randomly assign subjects to experimental groups to evenly distribute known and unknown confounders [21] [22].

- Restriction: Limit your study to a specific group (e.g., only one sex, a narrow age range) to eliminate variation from that confounder [21].

- Matching: For each subject in one group, select a subject in the comparison group with similar characteristics (e.g., age, weight) [21].

- Statistical Control: Use multivariate statistical models like Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA), linear regression, or logistic regression to adjust for confounders after data collection [21].

Quantitative Data on Key Confounding Factors

Table 1: Energy Availability Threshold Effect on Luteinizing Hormone (LH) Pulsatility [18]

| Energy Availability | LH Pulse Frequency | LH Pulse Amplitude | Effect Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 30 kcal/kg LBM/day | Unaffected | Unaffected | Normal |

| < 30 kcal/kg LBM/day | Decreases | Increases | Disrupted |

Table 2: Cortisol Response to 30-Minute Exercise at Different Times of Day [19]

| Time of Day | Baseline Cortisol | Cortisol Response Magnitude | Post-Exercise Suppression |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0700 h (Morning) | Significantly Higher | Moderate | Not observed |

| 1900 h (Evening) | Lower | Lower | Not observed |

| 2400 h (Night) | Lower | Greatest | Observed (~50 minutes) |

Table 3: Combined Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase and Time of Day on Physical Performance [20]

| Menstrual Phase | Time of Day | Cognitive Function (Stroop test) | Mood Disturbance (POMS) | Sleep Quality (PSQI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Phases | Afternoon | Significantly Better (p<0.001) | Lower | Better |

| Luteal Phase | Morning | Not specified | Significantly Higher (p<0.001) | Poorer |

Experimental Protocols for Controlling Confounders

Protocol A: Controlling for Energy Availability in Hormone Studies This protocol is designed to isolate and quantify the effect of low energy availability on reproductive hormones like LH [18].

- Participant Screening: Recruit regularly menstruating women. Exclude those using oral contraceptives or with irregular cycles.

- Baseline Assessment: Measure lean body mass (LBM) using DEXA or another reliable method.

- Energy Availability Manipulation: Over a 5-day controlled laboratory period:

- Set a fixed, high exercise energy expenditure (e.g., 15 kcal/kg LBM/day).

- Manipulate dietary intake to create different energy availability conditions (e.g., 10, 20, 30, 45 kcal/kg LBM/day).

- Blood Sampling: On the final day, collect blood samples at 10-minute intervals for 24 hours to assess LH pulsatility.

- Analysis: Compare LH pulse frequency and amplitude across the different energy availability levels to identify the disruption threshold.

Protocol B: Measuring Circadian Influence on Exercise-Induced Hormone Response This protocol outlines how to test the effect of time of day on cortisol and growth hormone (GH) responses to exercise [19].

- Participant Preparation: Use a standardized meal 12 hours before exercise and a supervised night of sleep to control for nutrition and sleep confounders.

- Experimental Design: A crossover design where each participant exercises on a treadmill for 30 minutes on three separate occasions, starting at 0700 h, 1900 h, and 2400 h.

- Control Days: Include identical control days without exercise for each time point.

- Blood Sampling: Obtain blood samples at 5-minute intervals for 1 hour before and 5 hours after exercise. Ensure participants do not sleep during sampling.

- Data Analysis: Determine the difference in serum cortisol and GH concentrations between the exercise day and the control day for each time of day. Analyze the magnitude and duration of the hormone response.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Energy Deficit Impact on LH

Diagram 2: Confounder Control Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Kits for Hormonal Exercise Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevance to Confounding Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Male Hormone Panel (e.g., Boston Heart Diagnostics) | Assesses key hormones like testosterone and cortisol. | Tracks hormonal balance fluctuations related to exercise stress and circadian rhythms [2]. |

| Comprehensive Hormone Profile (e.g., Doctor's Data) | Examines a wide range of hormones from a single sample. | Provides a broad view for detecting interactions between energy availability, stress, and menstrual cycle [2]. |

| ELISA Kits for LH, Cortisol, Testosterone, etc. | Quantifies specific hormone levels in serum/plasma. | Essential for measuring hormone responses in controlled exercise protocols [19] [18]. |

| Profile of Mood States (POMS) | A psychological rating scale to measure mood states. | Used to quantify mood disturbances linked to the luteal phase or overtraining [20]. |

| Stroop Test | A neuropsychological test to assess cognitive function. | Measures diurnal variations in cognitive performance in athletes [20]. |

| Statistical Software (R, SPSS, etc.) with appropriate packages | To perform multivariate regression and ANCOVA. | Critical for statistically adjusting for confounding variables during data analysis [21]. |

Implementing Rigorous Hormone Assessment: Methodological Protocols for Exercise Studies

FAQs on Bioassay Selection and Troubleshooting

1. What is the fundamental difference between serum, salivary, and urinary hormone measurements? The core difference lies in what fraction of the hormone they measure. Serum testing typically measures the total concentration of a hormone, including the portion that is bound to proteins and is biologically inactive. In contrast, saliva and urine measurements are used to assess the free, bioavailable fraction of the hormone that is active and can enter tissues [23] [24]. Saliva provides an instantaneous "snapshot" of free hormone levels at the time of collection, while urine provides an integrated average of hormone excretion over a period, such as 24 hours [25].

2. When should I use serum testing for hormone analysis in an exercise study? Serum testing is the conventional standard and is best suited for:

- Measuring peptide hormones like Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), Luteinizing Hormone (LH), and insulin [24].

- Establishing baseline levels in a clinical setting [24].

- Situations where simplicity and broad acceptance are priorities. A significant limitation is that it does not distinguish between bound and free hormone levels, which can be misleading if protein concentrations are altered [23].

3. What are the advantages of saliva testing for monitoring exercise-induced stress? Saliva testing is ideal for assessing the free, bioactive hormone levels such as cortisol, estradiol, and progesterone [24]. Its key advantage for exercise research is the non-invasive collection of multiple samples to map the diurnal cortisol pattern throughout the day [23] [24]. This makes it excellent for studying the impact of different exercise protocols on the circadian rhythm of stress hormones.

4. What unique insights does urinary hormone testing provide? Urine testing offers a deeper look into hormone metabolism. It is particularly helpful for:

- Identifying hormone metabolites to understand how hormones are being broken down in the body [24].

- Assessing adrenal health through the measurement of cortisol and its inactive form, cortisone [24].

- Providing a broader picture of hormone output over time (e.g., 24-hour collection) rather than a momentary snapshot [25].

5. My immunoassay results for cortisol are inconsistent. What could be the cause? Automated immunoassays, while commonly used, can lack specificity and show significant variability between different assay platforms [23]. They can cross-react with other similar compounds, leading to inaccurate readings. For more reliable and specific results, especially for complex matrices like saliva, consider using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), which offers improved sensitivity and specificity [23].

6. Why is it critical to match the sample type with the hormone supplementation method in a clinical trial? Using an inappropriate sample type can give a completely false representation of whole-body hormone exposure. For example:

- Saliva is not accurate for participants using troche or sublingual hormone therapies, as these can deliver artificially high hormone levels locally to the salivary glands [25].

- Urine testing is not recommended for assessing topical (e.g., creams) or oral hormone delivery, as it may show no uptake or extremely high levels, respectively, and does not accurately reflect tissue uptake [25]. Blood spot or saliva testing are more appropriate for these supplementation types.

7. How does the choice of assay method impact the validation of diagnostic tests like the Dexamethasone Suppression Test? Cortisol cut-off values used in dynamic tests like the Dexamethasone Suppression Test or the short Synacthen test were often established using older immunoassay methods. These diagnostic thresholds have not yet been fully validated for the newer, more specific LC-MS/MS assays [23]. Therefore, researchers and clinicians must use method-specific reference ranges to avoid misdiagnosis.

Experimental Protocols for Hormone Assessment in Exercise Research

The following protocol provides a framework for investigating acute hormonal responses to resistance exercise.

Protocol: Acute Hormonal Response to Various Resistance Training Modalities

- Objective: To determine the differential effects of maximum strength, muscular hypertrophy, and strength endurance exercise protocols on acute testosterone, cortisol, and growth hormone responses.

- Experimental Population: Young, resistance-trained males.

- Exercise Interventions: Participants perform multi-joint exercises (e.g., squat, bench press) in separate sessions using the following protocols [14]:

- Maximum Strength (MS): 5 repetitions at 88% of 1-Repetition Maximum (1-RM), 3-minute rest periods.

- Muscular Hypertrophy (MH): 10 repetitions at 75% of 1-RM, 2-minute rest periods.

- Strength Endurance (SE): 15 repetitions at 60% of 1-RM, 1-minute rest periods.

- Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Blood Sampling: Collect serum samples via venipuncture at four time points: pre-exercise (baseline), immediately post-exercise, and at 15 and 30 minutes into recovery [14].

- Assay Method: Analyze serum for total testosterone, cortisol, and growth hormone concentrations. LC-MS/MS is recommended for testosterone and cortisol for highest specificity [23].

- Key Parameters & Data Analysis:

- Compare area-under-the-curve (AUC) for each hormone across the three protocols.

- Statistically analyze the effect of the number of sets (e.g., 2, 4, or 6 sets) on the peak hormonal response and recovery pattern.

Comparison of Hormone Bioassay Methods

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of blood, salivary, and urinary hormone assessments to guide experimental selection.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Hormone Bioassay Methods

| Feature | Serum (Blood) | Saliva | Urine (24-hour) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone Fraction Measured | Total hormone (free + protein-bound) [23] | Free, bioavailable hormone [23] [24] | Free hormone & metabolites [24] |

| Temporal Representation | Point-in-time snapshot | Point-in-time snapshot [25] | Integrated average over collection period [25] |

| Key Applications | Peptide hormones; baseline levels; conventional diagnostics [24] | Diurnal cortisol patterns; steroid hormone monitoring [23] [24] | Hormone metabolism; long-term output assessment [24] |

| Advantages | Widely accepted; good for peptides | Non-invasive; reflects bioactive fraction; ideal for frequent sampling [23] | Comprehensive metabolic profile; non-invasive |

| Limitations | Invasive; influenced by serum protein levels [23] | Sensitive to local contamination (e.g., oral hormones) [25] [24] | Collection is burdensome; not reflective of tissue uptake for topicals [25] |

| Recommended Assay | Immunoassay or LC-MS/MS [23] | LC-MS/MS [23] | Immunoassay or LC-MS/MS [23] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Hormone Bioassays

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | High-specificity method of choice for measuring steroid hormones in serum and saliva; reduces cross-reactivity issues found in immunoassays [23]. |

| Validated Immunoassay Kits | For high-throughput analysis of specific hormones (e.g., growth hormone); requires validation for each sample matrix [23]. |

| Cortisol-Binding Globulin (CBG) | Critical understanding; serum cortisol levels are highly dependent on this binding protein, and alterations in CBG can mislead total cortisol measurements [23]. |

| DMSO & Solubilization Agents | For solubilizing lipophilic compounds in bioassays; optimal dilution protocols are necessary to avoid underestimating activity due to poor solubility [26]. |

| Standardized Reference Preparations | Essential for bioassay calibration; potency is determined by comparison with a standard to ensure accurate biological activity quantification [27]. |

Experimental Workflow for Hormone Bioassay Selection

The following diagram outlines a decision-making workflow for selecting the appropriate hormone bioassay, based on your specific research question.

Participant Preparation: Controlling Biological Variability

Why is proper participant preparation critical for reliable hormone measurements? Biological variability is a major source of error in hormone measurement studies. Proper participant preparation standardizes baseline conditions, ensuring that observed changes are due to the experimental intervention and not external confounders [28]. Key factors to control include diet, physical activity, circadian rhythms, and medication intake [29] [30].

Table: Key Participant Preparation Factors and Standardization Protocols

| Factor | Potential Impact on Hormone Measurements | Recommended Standardization Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Diet & Fasting [29] [30] | Significantly alters glucose, lipids, bone turnover markers, and insulin. Prolonged fasting (>16h) can cause false positives in glucose tolerance tests. | Fast for 10-12 hours prior to testing. Avoid prolonged fasting. Water is permitted to avoid dehydration and concentration of analytes like urea. |

| Physical Activity [30] | Strenuous exercise can deplete muscle glycogen for 24h, affecting insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and hormone concentrations. | Refrain from strenuous exercise for at least 24 hours before testing. Objectively monitor activity using wearables for precise standardization. |

| Circadian Rhythm [29] [31] | Hormones like cortisol, growth hormone, and testosterone exhibit strong diurnal variation. | Collect samples at a standardized time of day (e.g., morning for cortisol). Mid-morning collection is recommended for aldosterone-renin ratio [29]. |

| Posture [29] | Transitioning from supine to upright can reduce blood volume by 10%, increasing catecholamines, aldosterone, and renin. | For specific tests (e.g., plasma metanephrines), have participants lie supine for 30 minutes prior to venepuncture. Record posture during collection. |

| Medications & Supplements [29] [32] | Biotin (>5mg/day) causes severe interference in streptavidin-biotin based immunoassays. Many drugs and herbal supplements can alter analyte concentrations. | Withhold biotin supplements for at least 1-2 days prior to testing. Document all medications and supplements, and consult the laboratory on potential interferents. |

Sample Collection: Ensuring Sample Integrity from the Start

What are the most common pitfalls during blood sample collection and how can they be avoided? Errors during blood collection are a leading cause of pre-analytical errors, often resulting in sample rejection and the need for repeat sampling [29]. Key issues include improper patient identification, hemolysis, and contamination.

- Proper Patient Identification: Always use at least two permanent identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth) to match the patient to the request form and specimen labels. Avoid pre-labelling tubes before drawing blood [29].

- Avoiding Hemolysis: Hemolysis (rupture of red blood cells) can falsely elevate potassium, phosphate, and certain enzymes, while diluting or interfering with other analytes [29] [31]. To prevent in vitro hemolysis:

- Minimize tourniquet time.

- Use an appropriately sized needle.

- Ensure disinfectant alcohol has completely dried before venepuncture.

- Never transfer blood from a syringe to a tube through a needle.

- Gently invert tubes to mix; do not shake [29].

- Avoiding Contamination:

- IV Fluids: Never draw blood from an arm receiving intravenous fluids, as results will be contaminated [29].

- Cross-Contamination: Follow the correct order of draw to prevent carry-over of anticoagulants between tubes. A typical sequence is [29]:

- Blood culture tubes

- Sodium citrate tubes (e.g., for coagulation studies)

- Serum tubes (with or without clot activator, with or without gel)

- Heparin tubes

- EDTA tubes

- Fluoride/oxalate tubes (for glucose)

Sample Processing, Storage, and Handling: Preserving Analyte Stability

How do sample processing and storage conditions impact the stability of hormones like p-tau217 and metabolic hormones? The period between sample collection and analysis is critical. Ex vivo changes during this pre-analytical phase can significantly alter the apparent concentration of analytes, leading to incorrect conclusions [28] [33].

Table: Effects of Sample Handling on Analytical Results

| Handling Factor | Effect on Sample | Evidence-Based Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Centrifugation [33] | Removes fibrin clots and cellular debris. Non-centrifuged samples showed higher p-tau217 concentrations and lower diagnostic accuracy. | Centrifuge samples after thawing before analysis. This improves assay performance by providing a cleaner sample matrix. |

| Thawing Temperature [33] | Thawing plasma samples at room temperature vs. on ice showed no significant impact on p-tau217 correlations with pathology. | For the analyte studied (p-tau217), thawing temperature is less critical than centrifugation. Follow local laboratory protocols for specific analytes. |

| Freeze-Thaw Cycles [33] | Up to three freeze-thaw cycles had no significant impact on plasma p-tau217 concentrations. | For stable analytes, limited freeze-thaw cycles are acceptable. However, minimize cycles as some hormones (e.g., p-tau181 measured with Simoa) can degrade [33]. |

| Sample Type (Serum vs. Plasma) [28] | Serum and plasma have different matrices (e.g., protein content, presence of anticoagulants). This can lead to substantially different absolute concentrations for some hormones. | Use the sample type specified by the assay manufacturer and apply the appropriate reference ranges. Be consistent throughout a study. |

| Time to Processing [34] | Delayed processing can increase cell debris and dead cells, leading to decreased marker expression and non-specific antibody binding in flow cytometry. | Process samples within 24 hours of collection for most applications. For specific cell types or markers, a shorter timeframe may be necessary. |

Experimental Protocol: Testing Sample Handling Conditions

Based on a study investigating plasma p-tau217 [33], the following protocol can be adapted to test handling conditions for other analytes:

- Sample Collection: Collect blood into EDTA tubes.

- Initial Processing: Centrifuge blood (2000 g, 4°C, 10 min) within 30 minutes of collection. Aliquot plasma and store at -80°C.

- Variable Application:

- Thawing & Centrifugation: For each participant, use two frozen plasma tubes.

- Thaw one tube at room temperature (RT). Prepare two aliquots: one centrifuged at RT (10 min, 2000 g) and one not centrifuged.

- Thaw the second tube on ice. Prepare two aliquots: one centrifuged at +4°C and one not centrifuged.

- Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Use a new frozen plasma tube. Thaw at RT and prepare aliquots. Refreeze some aliquots to undergo one or two additional freeze-thaw cycles.

- Thawing & Centrifugation: For each participant, use two frozen plasma tubes.

- Analysis: Measure the analyte of interest (e.g., via immunoassay) in all aliquots and compare concentrations and associations with reference standards across the different handling conditions.

Sample Handling Experimental Workflow

Analytical Phase: Selecting and Validating Methods

What should researchers consider when choosing and performing hormone assays? The choice of analytical technique and its proper execution are fundamental to obtaining reliable data. Immunoassays, while common, are prone to specific interferences that must be recognized and managed [35] [32].

- Technique Selection: Immunoassay vs. Mass Spectrometry:

- Immunoassays are widely used but can suffer from cross-reactivity with similar molecules (especially for steroid hormones) and interference from proteins like heterophilic antibodies or macrocomplexes [35] [32]. For example, macroprolactin can cause falsely elevated prolactin readings [32].

- Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is generally superior for measuring small molecules like steroid hormones due to its high specificity and ability to measure multiple analytes simultaneously [35].

- Assay Verification: Do not assume a commercial assay kit will perform perfectly in your hands. Conduct an on-site verification before analyzing study samples. This includes checking precision, accuracy, and the reportable range to ensure the method meets your quality requirements [35].

- Heterophilic Antibody Interference: These are human antibodies that can bind to assay antibodies, leading to falsely high or low results. If results are clinically inconsistent, suspect this interference. Laboratories can use blocking tubes or re-analyze with alternative methods to mitigate this [31] [32].

Analytical Method Selection & Pitfalls

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Materials for Hormone Measurement Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| K2/K3 EDTA Tubes | Anticoagulant for plasma collection. Preferred for lymphocyte immunophenotyping and molecular assays [34]. | Chelates calcium. Can decrease expression of Ca2+-dependent markers like CD11b compared to heparin [34]. |

| Sodium Heparin Tubes | Anticoagulant for plasma collection. Preferred for granulocyte studies and cytogenetics [34]. | Not suitable for morphology. Can cause artefactual increase of CD11b on monocytes [34]. |

| Serum Tubes (with clot activator) | Collection of serum for a wide range of biochemical and hormonal tests. | Has a lower protein content than plasma. Fibrin clots can form if clotting time is insufficient [28]. |

| PBS with BSA Buffer | Washing and dilution buffer for flow cytometry and immunoassays. | The pH of the buffer (ideally 7.2-7.8) can significantly impact antibody binding and fluorochrome emission [34]. |

| Fix & Perm Solution | Cell fixation and permeabilization for intracellular (cytoplasmic) staining in flow cytometry [34]. | Staining protocols for surface markers only (SM) vs. surface plus cytoplasmic (SM+CY) can yield different results for some markers [34]. |

| Antibody Panels | Detection of specific cell surface and intracellular markers. | Titrate antibodies to optimal concentration. Use antibodies from the same manufacturer and lot number for a study to minimize variability [28] [34]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How long can blood samples be stored before processing, particularly for flow cytometry? For most flow cytometry applications, samples should be processed within 24 hours of collection when stored at room temperature (RT). However, this can be panel- and cell type-specific. Storing samples for 24 hours at RT is associated with a greater percentage of debris and cell doublets [34].

Q2: My immunoassay results are inconsistent with the clinical picture. What could be wrong? Several interferences could be at play:

- Biotin Interference: High doses of biotin (vitamin B7) supplements can cause falsely high or low results in streptavidin-biotin based immunoassays. Withhold biotin for at least 1-2 days before testing [29] [32].

- Heterophilic Antibodies: These human antibodies can cross-link assay antibodies, causing falsely elevated results. Suspect this when results are inexplicable. Use blocking reagents or alternative methods [31] [32].

- Hook Effect: In sandwich immunoassays, extremely high analyte concentrations can saturate the antibodies, leading to a falsely low result. If a large hormone-secreting tumor is suspected, request a 1:100 or greater sample dilution [32].

- Macrocomplexes: Complexes like macroprolactin (prolactin bound to IgG) are detected by immunoassays but are biologically inactive, leading to falsely high readings without clinical symptoms [32].

Q3: Should I use serum or plasma for hormone measurements? Both can be used, but they are not interchangeable. Serum and plasma have different matrices, which can lead to different absolute concentrations for the same analyte [28]. The choice depends on the assay manufacturer's recommendation. The critical factor is to be consistent throughout your entire study and use the appropriate reference ranges for your sample type.

Q4: How can I improve the reliability of my hormone measurements across a large study?

- Batch Analysis: Analyze all samples from the same study in a single batch, using immunoassays from the same manufacturer and lot number [28].

- Randomize Samples: Distribute samples from different experimental groups randomly across the assay plates to avoid batch effects [28].

- Use Internal Controls: Include independent quality control samples that cover the concentration range of interest in every assay run [35].

- Measure in Duplicate: Analyze samples at least in duplicate and repeat the measurement if the coefficient of variation (CV) exceeds 15% [28].

In exercise science and sports medicine, accurately measuring the body's hormonal response to physical activity is crucial for understanding physiological adaptation. Hormones like testosterone, cortisol, and growth hormone are not released at steady levels but in dynamic, pulsatile patterns. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) method provides a powerful technique to capture this total dynamic hormone exposure over time, integrating multiple measurements into a single, meaningful value that reflects the total hormonal response to an exercise stimulus [36] [37]. This guide details the methodologies, troubleshooting, and protocols for effectively applying AUC analysis in hormone research.

Core Concepts: AUC Formulas and Their Applications

Two primary formulas are widely used for AUC computation in endocrine research, each providing different information about hormonal secretion.

1. Area Under the Curve with Respect to Ground (AUCG)

This formula measures the total hormone concentration over time, reflecting the overall secretory activity [36].

- Formula:

AUCG = Σ [ (mᵢ + mᵢ₊₁) / 2 ] * tᵢWheremᵢis the hormone concentration at measurementi, andtᵢis the time interval between measurementsiandi+1[37].

2. Area Under the Curve with Respect to Increase (AUCI)

This formula measures the change in hormone concentration over time, factoring out the baseline level. It is particularly useful for analyzing the response to a specific stimulus, such as an exercise bout [36].

- Formula:

AUCI = AUCG - (m₁ * T)Wherem₁is the first (baseline) measurement andTis the total time span from the first to the last measurement [37].

Table: Comparison of AUCG and AUCI Methods

| Feature | AUCG (With Respect to Ground) | AUCI (With Respect to Increase) |

|---|---|---|

| Represents | Total hormone concentration across the measurement period | Time-dependent change in hormone concentration from baseline |

| Sensitive to Baseline | Yes | No |

| Ideal Use Case | Assessing overall hormonal status or load | Isolating the phasic response to a specific exercise intervention |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the most accurate method for calculating AUC in pharmacokinetics and hormone research? The Linear-Up Log-Down method is often considered the most accurate for profiles with a clear rise and fall, such as drug absorption and elimination. It uses the linear trapezoidal method when concentrations are increasing and the logarithmic trapezoidal method when concentrations are decreasing, better modeling the natural exponential decay of hormones or drugs [38].

Q2: My Python code throws a "x is neither increasing nor decreasing" error when I use sklearn.metrics.auc(). What went wrong?

This error occurs because the auc() function from scikit-learn is a general function that requires its x coordinates (e.g., False Positive Rates) to be monotonically increasing or decreasing. You likely passed raw predictions or incorrect values directly. To calculate the AUC for a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, you should first compute the curve itself and then the area [39].

- Incorrect:

- Correct:

- Simplest Correct Approach:

Q3: How does the menstrual cycle phase affect hormonal AUC measurements in female athletes? The menstrual cycle causes large, dynamic fluctuations in key reproductive hormones like estradiol-β-17 and progesterone. These hormones can, in turn, influence the levels and responses of other hormones (e.g., growth hormone). Research findings can be conflicting if the menstrual cycle phase is not rigorously controlled, as the inclusion of participants with anovulatory cycles or testing in different phases adds significant variance [40] [41]. It is recommended to verify the cycle phase through a combination of methods: calendar-based counting, urinary luteinizing hormone surge testing, and serum measurement of estrogen and progesterone at the time of testing [40].

Q4: What are the key biologic factors I need to control for in exercise-hormone studies? Beyond the exercise intervention itself, numerous biologic factors can introduce variance into hormone measurements. To increase the homogeneity of your sample and the validity of your results, you should monitor, control, and adjust for [41]:

- Sex and Age: Hormonal profiles differ significantly between sexes post-puberty and change with age.

- Body Composition: Levels of adiposity can greatly influence cytokines and hormones like insulin and leptin.

- Mental Health: Conditions like high anxiety or depression can alter resting levels of catecholamines and cortisol.

- Circadian Rhythms: Many hormones exhibit strong circadian variation.

- Menstrual Status and Phase (in females): As noted in Q3.

Common Computational and Methodological Errors

Table: Troubleshooting Common AUC Calculation Issues

| Error / Issue | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| AUC overestimation during elimination phase | Using linear trapezoidal method for exponentially declining concentrations | Switch to logarithmic trapezoidal or Linear-Up Log-Down method for decreasing concentration points [38]. |

| Incomparable results between research groups | Use of different, unreported AUC formulas (AUCG vs. AUCI) | Calculate and report both AUCG and AUCI to provide a complete picture of total concentration and change from baseline [36]. |

| High variance in hormonal AUC outcomes within a group | Failure to control for key biologic factors (e.g., time of day, fitness level, body composition) | Implement strict participant screening and matching protocols. Standardize testing times for all subjects [41]. |

Experimental Protocols for Hormone AUC in Exercise Research

Standardized Protocol for Blood Collection and AUC Calculation

This protocol outlines the key steps for collecting hormone data and computing the AUC in an exercise intervention study.

1. Pre-Exercise Preparation:

- Participant Screening: Control for key biologic factors. Screen participants for sex, age, fitness level, body composition, and mental health status. For female participants, verify menstrual cycle phase (e.g., luteal phase progesterone >16 nmol/L) [40] [41].

- Standardization: Conduct all tests at the same time of day for each participant to account for circadian rhythms. Ensure participants are fasted and have abstained from strenuous exercise, caffeine, and alcohol for a pre-defined period.

2. Blood Collection Schedule:

- Draw a baseline (pre-exercise) blood sample.

- Administer a standardized and quantifiable exercise bout (e.g., resistance training: 3 sets of 8-10 reps at 80% 1RM, with 90s rest) [2].

- Collect post-exercise blood samples at multiple predetermined time points (e.g., immediately post, 15, 30, 60, and 90 minutes post-exercise) to capture the dynamic hormonal response [36] [37].

3. Sample Processing and Analysis:

- Centrifuge blood samples to separate serum or plasma and freeze at -80°C until analysis.

- Assay all samples from a single participant in the same batch to minimize inter-assay variance using reliable methods (e.g., ELISA, Radioimmunoassay).

4. Data Analysis and AUC Calculation:

- Record the exact hormone concentration (

mᵢ) and the precise time from baseline for each sample (tᵢ). - Input the data into a statistical software package (e.g., R, Python, Phoenix WinNonlin).

- Calculate both AUCG (total hormonal output) and AUCI (exercise-induced hormonal change) using the trapezoidal formulas [36] [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Materials for Hormone Response Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Serum Blood Collection Tubes (e.g., clot activator tubes) | Collection of whole blood from which serum is extracted for hormone analysis. |

| Centrifuge | Rapid separation of serum or plasma from blood cells post-collection. |

| -80°C Freezer | Long-term storage of serum/plasma samples to preserve hormone integrity before batch analysis. |

| ELISA or RIA Kits (e.g., for Testosterone, Cortisol, Growth Hormone) | Quantitative measurement of specific hormone concentrations in the serum/plasma samples. |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) Urine Test Strips | Verification of ovulation and menstrual cycle phase in female participants as part of screening [40]. |

Statistical Software (R, Python with sklearn, Phoenix WinNonlin) |

Implementation of trapezoidal rule for AUC calculation and subsequent statistical analysis [39] [37] [38]. |

Methodological Visualizations

Decision Workflow for AUC Method Selection

This diagram helps researchers select the most appropriate AUC calculation method based on their research question and data characteristics.

FAQs: Hormone Sampling Protocols

Q: When is the peak cortisol response to exhausting exercise typically observed? A: The peak cortisol response often occurs during recovery, not at the immediate end of exercise. One study found that 73.5% of peak cortisol responses (25 out of 34 highly trained male subjects) were observed between 30 and 90 minutes into the recovery period after volitional exhaustion [42]. This suggests that to capture the peak response, blood sampling should continue for at least one hour into recovery [42].

Q: Can saliva or urine replace blood for measuring Growth Hormone (GH) in exercise studies? A: While less invasive, saliva and urine might not be direct substitutes for venous blood sampling. Research shows that although GH concentrations in saliva and urine are correlated with serum levels, the absolute concentrations and their patterns of appearance differ significantly across these media post-exercise [43]. For tracking the precise pattern of exercise-induced GH response, venous sampling remains the most reliable method, and the same medium should be used consistently throughout a study [43].

Q: What are critical pitfalls in hormone measurement techniques that can compromise study validity? A: Key pitfalls include:

- Technique Specificity: Immunoassays, commonly used for peptide hormones, can suffer from cross-reactivity and matrix effects, leading to inaccurate readings. Mass spectrometry methods are often superior for steroid hormones [35].

- Binding Protein Interference: The accuracy of total steroid hormone measurements (e.g., testosterone, cortisol) can be compromised in subjects with unusually high or low levels of binding proteins (e.g., SHBG) [35].

- Insufficient Assay Verification: Relying solely on manufacturer's data without on-site verification of the assay's performance with study-specific samples can lead to unreliable results. Internal quality controls spanning the expected concentration range are essential [35].

Q: How does energy availability affect hormone profiles in athletes? A: Low energy availability (LEA), common during intense competition preparation, significantly disrupts hormone profiles. Studies on physique athletes show that LEA leads to decreased anabolic hormones like testosterone and IGF-1, and can increase catabolic hormones like cortisol. This hormonal environment can suppress reproductive function, reduce muscle strength, and contribute to mood disturbances, aligning with the Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) syndrome [44] [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent or Unexplainable Hormonal Data

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-optimal sampling timing. | Review literature for hormone-specific peak response windows (e.g., cortisol peaks post-exercise) [42]. | Extend sampling into the recovery period; pilot test to define the kinetic response curve for your specific protocol. |

| Inappropriate assay technique. | Audit your method: Was an immunoassay used for steroids in a population with atypical binding protein levels? [35] | Validate your assay within your study population. Consider switching to mass spectrometry for steroid hormones [35]. |

| Poor control group selection. | Evaluate if the control condition raises different participant expectations for cognitive or performance outcomes [46] [47]. | Use an active control group (e.g., light exercise, stretching) that matches the experimental condition's expectations where possible [46]. |

| Unaccounted for energy deficiency. | Monitor and calculate participants' Energy Availability (EA) [44]. | Ensure participants are in a state of energy balance to avoid confounding hormonal results from energy deficit [44]. |

Issue: High Variability in Hormone Responses Between Subjects

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized pre-test conditions. | Review participant instructions for diet, fasting, caffeine, and previous exercise [42]. | Implement and verify strict standardization for these factors for 24-48 hours before testing [42] [48]. |

| Individual variance in physiology. | This is a natural aspect of endocrine response, even in controlled studies [42]. | Increase sample size, use a within-subjects design where feasible, or employ stratification/minimization during randomization to balance known confounders [48]. |

| Inconsistent exercise intensity. | Use objective intensity measures (e.g., %VO2max, %HRmax, power output) instead of perceived exertion alone. | Calibrate exercise equipment regularly. Use gas analysis or heart rate monitors to ensure intensity is uniform across all subjects and sessions. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Capturing the Peak Cortisol Response to Exhaustive Exercise

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the timing of peak cortisol levels [42].

- Participants: Highly trained male endurance athletes (n=34).

- Pre-test Standardization: Participants reported to the lab in a 2.5-hour fasted state, having abstained from strenuous activity, alcohol, and sex for 24 hours, and caffeine for 12 hours [42].

- Baseline Sampling: After a 30-minute supine rest, an indwelling catheter is placed, and a baseline (Pre-Ex) blood sample is drawn [42].

- Exercise Bout: Participants run on a treadmill at an intensity corresponding to ~100% of their ventilatory threshold until volitional exhaustion (mean time ~82 minutes). Strong verbal encouragement is given at the end to ensure true exhaustion [42].

- Post-Exercise Sampling:

- Impost: Blood sample is taken immediately upon exhaustion.

- Recovery: After a 5-minute active cool-down, participants rest supine. Blood samples are taken at 30 (30min), 60 (60min), and 90 minutes (90min) into recovery [42].

- Sample Analysis: Blood is centrifuged, and plasma is stored at -80°C until analysis via a validated radioimmunoassay [42].

Quantitative Data: Cortisol Peak Timing

The table below summarizes the frequency of peak cortisol observations at different time points from the referenced protocol [42].

| Time Point | Number of Subjects Exhibiting Peak Cortisol | Percentage of Total Peaks |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate Post-Exercise (Impost) | 9 | 26.5% |

| 30-min Recovery | 21 | 61.8% |

| 60-min Recovery | 3 | 8.8% |

| 90-min Recovery | 1 | 2.9% |

| Total Peaks in Recovery | 25 | 73.5% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Hormone Exercise Research |

|---|---|

| EDTA Treated Vacutainer Tubes | Collects blood plasma samples; EDTA acts as an anticoagulant to prevent clotting [42]. |

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kits | A highly sensitive technique for quantifying hormone concentrations (e.g., cortisol) in plasma or serum samples [42]. |

| Open-Circuit Spirometry System | Measures respiratory gases (VO2, VCO2) to objectively determine exercise intensity and maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) [42]. |

| Isokinetic Dynamometer | Provides objective, high-fidelity measurement of muscular strength and torque as a performance outcome correlated with hormonal changes [44]. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | The gold-standard method for measuring steroid hormones, offering superior specificity by minimizing cross-reactivity issues common in immunoassays [35]. |

Methodological Diagrams

Control Group Selection Logic

Hormone Measurement Workflow

Troubleshooting Measurement Artifacts: Mitigating Pre-Analytical and Analytical Error

Troubleshooting Guide: Hormone Assay Interferences

The High Dose Hook Effect

Q: My patient has a large pituitary mass, but their prolactin is only mildly elevated. Why is this, and how can I get an accurate result?

A: You are likely encountering the High Dose Hook Effect. This is an assay interference occurring in sandwich immunoassays when the hormone (analyte) concentration is so exceedingly high that it saturates both the capture and signal antibodies, preventing the formation of the measurable "sandwich" complex. This results in a falsely low or normal reading [49].

- Mechanism: In a standard sandwich assay, the analyte binds to the capture antibody on a solid surface, and then a signal antibody binds to a different epitope of the analyte. In the hook effect, an overabundance of analyte binds to both antibodies separately, but not in the correct sandwich formation, leading to a low signal after washing [49].

- Hormones Commonly Affected: Prolactin (in macroprolactinomas), beta human chorionic gonadotropin (B-HCG) in choriocarcinoma, thyroglobulin in thyroid cancer, and prostate-specific antigen in metastatic prostate cancer [49].

The diagram below illustrates the mechanism of the Hook Effect.

Experimental Protocol for Detection and Resolution:

- Clinical Indication: Suspect hook effect with a large (>4 cm) pituitary tumor or widely metastatic disease where high hormone levels are expected [49].