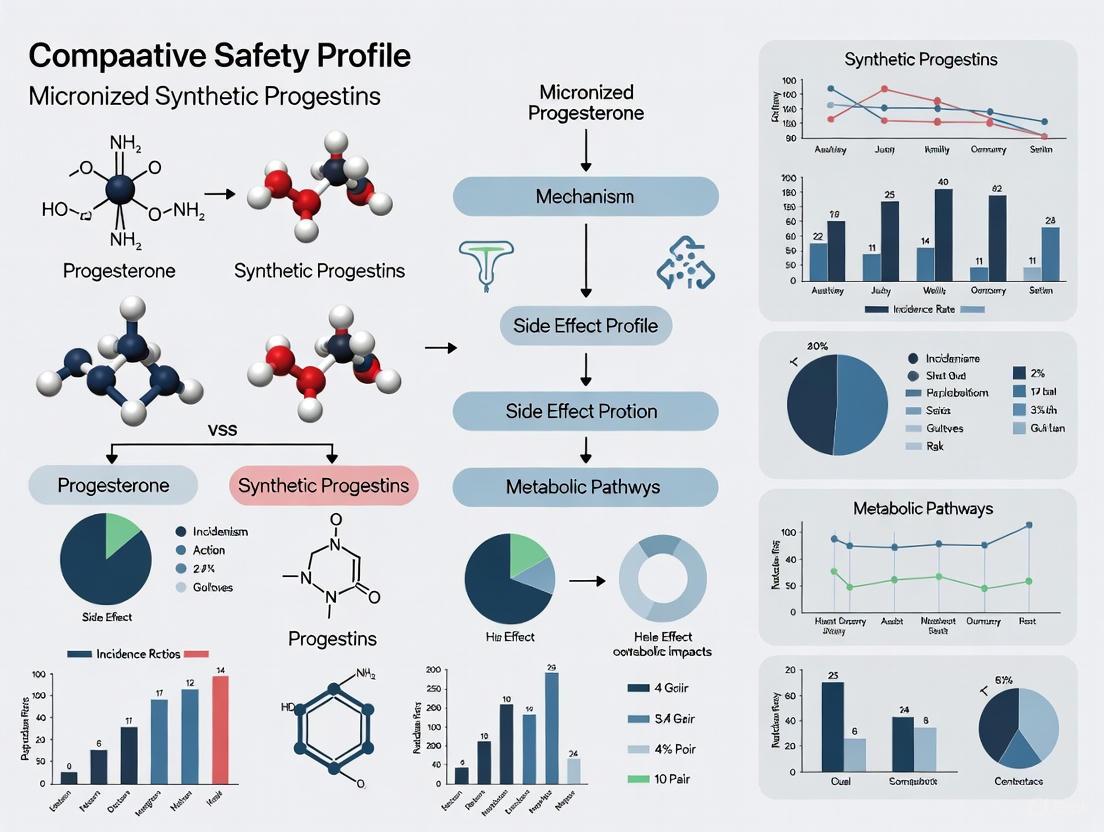

Micronized Progesterone vs. Synthetic Progestins: A Comparative Analysis of Safety Profiles for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive, evidence-based analysis of the distinct safety and pharmacodynamic profiles of micronized progesterone (MP) and synthetic progestins.

Micronized Progesterone vs. Synthetic Progestins: A Comparative Analysis of Safety Profiles for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, evidence-based analysis of the distinct safety and pharmacodynamic profiles of micronized progesterone (MP) and synthetic progestins. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational biochemistry, clinical application methodologies, and head-to-head comparative data. The review critically examines the implications of molecular structure on receptor binding, metabolic pathways, and long-term risks, including breast cancer, cardiovascular events, and neurological effects. It concludes with a discussion on the future of progestogen development and the importance of molecule-specific safety evaluations in clinical practice and research.

Molecular Foundations and Mechanisms of Action: Beyond a Single Class

In endocrine pharmacology, the terms "progesterone" and "progestin" refer to distinct molecular classes with important therapeutic differences. Natural progesterone is a bioidentical steroid hormone (pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione) produced by the corpus luteum, adrenal glands, and placenta during pregnancy [1]. In contrast, progestins are synthetic molecules created in laboratories to mimic progesterone's effects but with modified chemical structures [1] [2].

The fundamental distinction lies in their origin and molecular structure: natural progesterone is identical to the hormone produced by the human body, while progestins are synthetic analogs designed to overcome the poor oral bioavailability and rapid metabolic decay of naturally-occurring progesterone [1]. This structural divergence results in significantly different pharmacodynamic profiles, safety implications, and clinical applications, making the choice between these molecules particularly relevant for drug development professionals considering therapeutic safety profiles.

Molecular Structures and Classification

Natural Progesterone and Micronization

Natural progesterone has a characteristic C21-steroid structure with a cyclic hydrocarbon skeleton that forms the basis for all progestogenic activity [1]. To overcome its naturally poor oral absorption due to extensive first-pass metabolism, a pharmacotechnical micronization process was developed. Micronized progesterone (MP) involves reducing progesterone particle size to enhance dissolution and bioavailability, creating an effective oral formulation that preserves the native hormone's structure [1] [3].

Synthetic Progestin Classifications

Synthetic progestins are categorized through two primary classification systems: by generation (when introduced to market) or by structural derivation [4].

Table: Structural Classification of Synthetic Progestins

| Structural Class | Derivation | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnanes | Progesterone | Medroxyprogesterone acetate, Nomegestrol acetate | Derived from natural progesterone backbone [4] |

| Estranes | Testosterone | Norethindrone, Norethindrone acetate | Moderate androgenic activity [4] [5] |

| Gonanes | Testosterone | Levonorgestrel, Desogestrel, Norgestimate | Lower androgenic activity than estranes; used in contraceptives [4] [5] |

Table: Generational Classification of Synthetic Progestins

| Generation | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| First | Norethindrone, Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Early synthetic formulations [4] |

| Second | Levonorgestrel | Improved potency and selectivity [4] |

| Third | Desogestrel, Norgestimate, Gestodene | Reduced androgenic effects [4] |

| Fourth | Drospirenone | Antiandrogenic and antimineralocorticoid properties [4] |

The structural modifications in progestins alter their receptor binding affinities beyond the progesterone receptor, leading to different side effect profiles compared to natural progesterone [4] [5].

Mechanism of Action: Signaling Pathways and Receptor Interactions

Genomic Signaling Pathways

Both natural progesterone and synthetic progestins exert their primary effects through genomic signaling pathways involving intracellular progesterone receptors (PRs) [1] [6].

Progesterone receptors exist in two main isoforms: PR-A and PR-B, encoded by a single gene on chromosome 11q22 [1]. These receptors are located throughout the body in reproductive tissues, breast, brain, vascular endothelium, and other sites [1]. When unbound, PR exists as a monomer; ligand binding induces conformational change and dimerization, enabling the receptor complex to bind progesterone response elements (PREs) on DNA and regulate gene transcription [1] [6].

Non-Genomic Signaling and Neurosteroid Activity

Natural progesterone exhibits important non-genomic signaling pathways not typically shared by synthetic progestins [6]. As a neurosteroid, progesterone and its metabolites (particularly allopregnanolone) act as positive modulators of GABA-A receptors, producing anxiolytic, antidepressant, anesthetic, and sleep-promoting effects [1] [6]. These neuroactive properties are particularly pronounced with oral micronized progesterone, which undergoes metabolism to active neurosteroids [1] [7].

Additional non-genomic actions include interaction with membrane receptors such as oxytocin receptors and blockade of calcium influx in uterine smooth muscle, contributing to uterine relaxation [6].

Receptor Cross-Talk and Selectivity Profiles

A critical distinction between natural and synthetic molecules lies in their receptor binding selectivity. While both classes bind progesterone receptors, they display markedly different affinities for other steroid receptors [6].

This differential receptor activation profile explains many of the side effects associated with synthetic progestins, including their androgenic, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid activities [6] [5]. Natural progesterone exhibits a more selective binding profile that more closely mimics the body's endogenous signaling.

Comparative Safety Profiles: Experimental Evidence

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Safety

Substantial clinical evidence demonstrates differentiated cardiovascular and metabolic safety profiles between natural and synthetic progestogens.

Table: Cardiovascular and Metabolic Risk Profile Comparison

| Safety Parameter | Micronized Progesterone | Synthetic Progestins | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Risk | Lower risk | Increased risk, especially 3rd/4th generation | PEPI Trial; large observational studies [1] |

| Lipid Metabolism | Neutral or favorable effects on HDL | Decreased HDL; increased LDL & triglycerides | Multiple clinical trials [1] [5] [3] |

| Carbohydrate Metabolism | Minimal impact on insulin/glucose | Increased insulin & glucose levels | Metabolic studies [4] [3] |

| Blood Pressure | Neutral effects | Mild increase in blood pressure | Clinical monitoring data [4] |

The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial demonstrated that micronized progesterone preserved HDL cholesterol levels without the unfavorable lipid changes associated with medroxyprogesterone acetate [3]. This metabolic advantage positions micronized progesterone as the preferred option for patients with increased cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors [1].

Breast Cancer Risk

The association between hormone therapy and breast cancer risk differs significantly between progesterone types. While combined estrogen-progestin therapy has demonstrated increased breast cancer risk in large studies like the Women's Health Initiative, evidence suggests micronized progesterone does not increase breast cancer risk to the same extent as synthetic progestins [1]. This differential risk profile represents a critical consideration for drug development and clinical use.

Central Nervous System Effects

As a neurosteroid, natural progesterone and its metabolites (particularly allopregnanolone) exert GABA-ergic effects that produce distinctly different CNS profiles compared to synthetic progestins [1] [6] [7].

Table: CNS Effects Comparison

| Effect | Micronized Progesterone | Synthetic Progestins | Clinical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mood Impact | Anxiolytic/antidepressant effects; less dysphoria | Potential mood disturbance, irritability | Randomized controlled trials [1] [5] |

| Sleep Quality | Improved sleep architecture; reduced awakenings | Limited or negative impact | Phase III trial in perimenopause [7] |

| Cognitive Effects | Improved working memory in menopause | Not documented | Clinical studies [1] |

| Sedation | Mild, transient drowsiness (managed with bedtime dosing) | Not typically reported | Safety and tolerability studies [1] [8] |

A 2023 Phase III randomized controlled trial specifically demonstrated that perimenopausal women receiving oral micronized progesterone (300mg at bedtime) reported significantly improved sleep quality and decreased night sweats compared to placebo, without increased depression scores [7].

Research Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Receptor Binding Assays

Purpose: To quantify binding affinities of natural and synthetic progestogens for progesterone receptors and related steroid receptors.

Detailed Protocol:

- Receptor Preparation: Isolate progesterone receptors from human uterine tissue or use commercially available human PR kits

- Radioligand Preparation: Tritium-labeled progesterone ([³H]-progesterone) as reference ligand

- Competitive Binding: Incubate receptors with radioligand and increasing concentrations of test compounds (micronized progesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone, etc.)

- Separation and Measurement: Use charcoal-dextran separation to bound/free ligand; measure radioactivity via scintillation counting

- Data Analysis: Calculate IC50 values and relative binding affinities (RBA) with progesterone as reference (RBA=100)

Key Experimental Controls:

- Include receptor-specific competitors to determine selectivity

- Test binding across PR-A and PR-B isoforms separately

- Evaluate binding to androgen, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptors

This methodology reliably demonstrates the higher receptor selectivity of natural progesterone compared to synthetic progestins, which show significant cross-reactivity with androgen and other steroid receptors [6].

Endometrial Protection Studies

Purpose: To evaluate endometrial hyperplasia prevention in menopausal hormone therapy.

Detailed Protocol:

- Study Population: Postmenopausal women with intact uteri receiving estrogen therapy

- Intervention Groups:

- Group 1: Estrogen alone

- Group 2: Estrogen + micronized progesterone (200mg daily, 12 days/month)

- Group 3: Estrogen + medroxyprogesterone acetate (5-10mg daily, 12 days/month)

- Duration: 1-3 year study periods

- Primary Endpoint: Incidence of endometrial hyperplasia assessed by endometrial biopsy

- Secondary Endpoints: Bleeding patterns, patient satisfaction, metabolic parameters

Assessment Methods:

- Endometrial biopsy at baseline and study conclusion

- Transvaginal ultrasound for endometrial thickness

- Daily bleeding diaries

- Lipid profiles, carbohydrate metabolism markers

The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial utilized similar methodology to demonstrate equivalent endometrial protection between micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins, but with superior metabolic effects [3].

Neurosteroid Activity Assessment

Purpose: To evaluate GABA-ergic activity of progesterone metabolites.

Detailed Protocol:

- Animal Models: Use ovariectomized rodent models to control endogenous hormone production

- Drug Administration:

- Oral micronized progesterone (300mg human equivalent)

- Synthetic progestins (medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone)

- Vehicle control

- Behavioral Testing:

- Elevated plus maze for anxiety behavior

- Forced swim test for antidepressant activity

- Electroencephalography (EEG) for sleep architecture

- Molecular Analysis:

- Brain tissue analysis for allopregnanolone levels

- GABA-A receptor subunit expression changes

- Pharmacological Challenges: Use GABA-A antagonists to confirm mechanism

This experimental approach has demonstrated that natural progesterone, through its metabolite allopregnanolone, produces significant anxiolytic and sleep-promoting effects not observed with synthetic progestins [1] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents for Progestogen Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function in Research | Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| T47D Breast Cancer Cells | Express high levels of progesterone receptors | PR binding assays; gene regulation studies [1] |

| Ishikawa Endometrial Cells | Endometrial adenocarcinoma line with steroid responsiveness | Endometrial protection assays; decidualization studies [1] |

| [³H]-Progesterone | Radiolabeled natural progesterone | Reference compound for receptor binding assays [6] |

| PR-Knockout Mouse Models | Genetically modified lacking progesterone receptors | Mechanism of action studies; receptor specificity confirmation [1] |

| Specific PR Antibodies | Isoform-specific detection (PR-A vs PR-B) | Immunohistochemistry; Western blot; receptor localization [1] |

| GABA-A Receptor Antagonists | Block GABA receptor function (bicuculline, gabazine) | Neurosteroid mechanism studies [6] |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry | Precise quantification of progesterone and metabolites [7] |

The molecular distinctions between natural bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins translate into significantly different clinical safety profiles. Natural micronized progesterone demonstrates advantages in metabolic neutrality, neurosteroid benefits, and breast safety, while providing equivalent endometrial protection. Synthetic progestins, while effective for many indications, carry greater risks of metabolic disruption, androgenic side effects, and thromboembolic complications.

For drug development professionals, these differential safety profiles support the strategic selection of micronized progesterone for patients with increased cardiovascular, metabolic, or breast cancer risk factors. Future research should focus on developing increasingly selective progestogenic compounds that maintain the therapeutic benefits of natural progesterone while optimizing its safety profile for specific patient populations.

Pharmacodynamics and Receptor Binding Affinities

The pharmacodynamic profiles of progestogens—encompassing both natural progesterone and synthetic progestins—are fundamentally determined by their distinct interactions with steroid hormone receptors and subsequent signaling pathways. Progesterone, the endogenous hormone, binds to its specific receptors to induce targeted progestational effects, but it also exhibits the ability to interact with the binding sites of other steroids, leading to anti-estrogenic, anti-androgenic, and anti-mineralocorticoid effects [9]. Synthetic progestins, developed to mimic progesterone's actions while improving bioavailability and half-life, display a wide spectrum of binding affinities for various steroid receptors, resulting in diverse and sometimes off-target physiological effects [10] [11]. This comparative analysis delineates the fundamental differences in receptor binding affinities, signaling mechanisms, and downstream biological effects between micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins, providing a scientific foundation for understanding their comparative safety profiles.

Receptor Binding Affinity Profiles

The binding affinity of a progestogen for various steroid receptors dictates its primary activity and side effect profile. Unlike synthetic progestins, natural progesterone exhibits a specific binding pattern that contributes to its unique safety and efficacy characteristics.

Table 1: Relative Receptor Binding Affinities of Progesterone and Synthetic Progestins

| Compound | PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 50 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 100 | 0 | 36 |

| Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) | 100 | 20 | 0 | 29 | 162 | 0 | 100 |

| Norethisterone | 75 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Levonorgestrel | 150 | 45 | 0 | 1 | 75 | 50 | 0 |

| Drospirenone | 100 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 230 | 0 | 0 |

Data compiled from [12] and [10]. Values are percentages (%), with reference ligands (100%) being promegestone for PR, metribolone for AR, E2 for ER, DEXA for GR, aldosterone for MR, DHT for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. PR=Progesterone Receptor, AR=Androgen Receptor, ER=Estrogen Receptor, GR=Glucocorticoid Receptor, MR=Mineralocorticoid Receptor, SHBG=Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin, CBG=Corticosteroid-Binding Globulin.

The data reveals critical differentiators:

- Progesterone's Anti-Mineralocorticoid Activity: Progesterone acts as a potent antimineralocorticoid, possessing 100% of aldosterone's affinity for the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and functioning as an antagonist at this receptor. This underlies its natriuretic (sodium-excreting) effect and potential benefits for blood pressure and water retention [12]. A 200 mg oral dose is considered roughly equivalent to 25-50 mg of spironolactone [12].

- Lack of Androgenic Activity: Progesterone shows negligible affinity for the androgen receptor (AR) and is clinically neither androgenic nor antiandrogenic. This contrasts sharply with many synthetic progestins (e.g., levonorgestrel, norethisterone) that exhibit significant androgenic potential due to their structural derivation from testosterone [9] [12].

- Variable Glucocorticoid Activity: Progesterone binds weakly to the GR (about 10% of dexamethasone's affinity) but appears to have minimal clinical glucocorticoid activity. Conversely, some synthetic progestins like MPA and gestodene demonstrate more substantial GR binding and glucocorticoid effects, which can influence metabolism and immune function [12] [10].

Key Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms of Action

The genomic and non-genomic actions of progestogens mediate their effects on target tissues. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways.

Figure 1: Core signaling pathways of progesterone and synthetic progestins. Colored pathways highlight distinct mechanisms: green for primary genomic/non-genomic actions, red for off-target effects, and blue for neurosteroid effects.

The pathways delineated in Figure 1 involve several distinct mechanistic principles:

- Genomic Signaling: The classic mechanism involves ligand binding to nuclear PRs (PR-A and PR-B), receptor dimerization, binding to Progesterone Response Elements (PREs) in target gene promoters, and recruitment of co-regulators to activate or repress transcription. This process, which takes minutes to hours, mediates many of the endometrial and reproductive effects [6] [11].

- Non-Genomic Signaling: Progesterone and progestins can also activate membrane Progesterone Receptors (mPRs) and other membrane-associated receptors, leading to rapid intracellular signaling (e.g., calcium influx modulation) that affects processes like uterine contractility within seconds to minutes [6].

- Neurosteroid Activity: A unique property of progesterone is its metabolism in the nervous system to allopregnanolone, a potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. This pathway underlies progesterone's anxiolytic, antidepressant, and neuroprotective effects, which are not typically shared by synthetic progestins [6] [13].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Analysis

Robust experimental methodologies are required to quantify the binding affinities and functional activities described. The following protocols are foundational to the field.

Receptor Binding Assay (Competitive Displacement)

Objective: To determine the relative binding affinity (RBA) of a test compound for a specific steroid receptor (e.g., PR, AR, GR, MR).

Methodology:

- Receptor Source: Prepare cytosolic or nuclear extracts from receptor-positive tissues (e.g., animal uterus, mammary gland) or use commercially available human recombinant steroid receptors.

- Radioligand Incubation: Incubate the receptor preparation with a fixed concentration of a tritiated (³H) reference ligand (e.g., ³H-promegestone for PR, ³H-aldosterone for MR) and increasing concentrations of the unlabeled test compound (progesterone or synthetic progestin).

- Separation and Quantification: After equilibrium is reached, separate the receptor-bound radioligand from the free radioligand using charcoal-dextran adsorption, gel filtration, or other methods. Measure the radioactivity in the bound fraction using a scintillation counter.

- Data Analysis: The RBA is calculated as the ratio of the molar concentration of unlabeled reference ligand required to displace 50% of the bound radioligand (IC50) to the IC50 of the test compound, expressed as a percentage. The reference ligand's RBA is set at 100% [12] [10].

In Vivo Endometrial Transformation Assay (McGinty Test)

Objective: To assess the progestational potency and efficacy of a compound by its ability to induce secretory transformation of an estrogen-primed endometrium.

Methodology:

- Animal Model: Use immature female rabbits (e.g., New Zealand White strain).

- Estrogen Priming: Pre-treat the animals with subcutaneous injections of estradiol for approximately 6 days to stimulate endometrial proliferation.

- Progestogen Administration: Following priming, administer the test progestogen (progesterone or synthetic progestin) typically via subcutaneous injection for 5 consecutive days. Include control groups (estrogen-only and vehicle).

- Histological Evaluation: Euthanize the animals and excise the uteri. Process the endometrial tissue for histological sectioning and staining (e.g., Hematoxylin and Eosin). A positive progestational effect is scored based on the observed morphological changes, such as glandular tortuosity and secretory activity, often using a standardized scale (e.g., the McPhail index) [11] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Progestogen Pharmacodynamics Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Human Steroid Receptors | High-purity preparations of PR, AR, GR, MR for standardized in vitro binding and transactivation assays, minimizing variability from tissue extracts [10]. |

| Tritiated (³H) Ligands | Radiolabeled reference steroids (e.g., ³H-promegestone, ³H-aldosterone) used as tracers in competitive receptor binding assays to quantify affinity [12]. |

| PR Isoform-Specific Cell Lines | Engineered cell lines (e.g., expressing only PR-A or PR-B) to dissect the unique genomic and functional contributions of each receptor isoform [11]. |

| Specific Receptor Antagonists | Compounds like RU-486 (PR antagonist) or spironolactone (MR antagonist) used as control tools to confirm receptor-mediated mechanisms of action [6]. |

| Animal Models for Endometrial Response | Immature female rabbits or ovariectomized rats for in vivo bioassays (e.g., McGinty test) to evaluate the endometrial efficacy of progestogens [13]. |

Implications for Safety and Clinical Outcomes

The differential pharmacodynamics of micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins translate into meaningful differences in clinical safety profiles, particularly in long-term hormone therapy.

- Breast Cancer Risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies concluded that estrogen therapy combined with micronized progesterone is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer (Relative Risk 0.67; 95% CI 0.55–0.81) compared to estrogen therapy combined with synthetic progestins [14]. This is biologically plausible because synthetic progestins, unlike progesterone, may exert growth-promoting effects on breast tissue [14] [15].

- Metabolic and Cardiovascular Parameters: The PEPI trial demonstrated that progesterone, unlike MPA, does not negate the beneficial effect of estrogen on HDL-C ("good" cholesterol) [14]. Furthermore, progesterone's anti-mineralocorticoid activity may contribute to neutral or beneficial effects on blood pressure, in contrast to certain synthetic progestins that can cause water retention and hypertension in susceptible individuals [9] [12].

- Neurosteroid and CNS Effects: The metabolism of progesterone to allopregnanolone confers unique neuroprotective, anxiolytic, and potential cognitive benefits via GABAA receptor modulation. Most synthetic progestins lack this metabolic pathway and its associated positive neurological effects [6] [13].

Key Metabolic Pathways and Neuroactive Metabolites

The metabolic fate of progestogens is a critical determinant of their clinical efficacy and safety profile. This review provides a comparative analysis of the metabolic pathways and neuroactive metabolites of micronized progesterone (P4) versus synthetic progestins, examining how these differences translate into distinct pharmacological and clinical outcomes. Understanding these pathways is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize therapeutic interventions in women's health, particularly in the context of hormone replacement therapy and contraceptive development.

Metabolic Pathways of Progestogens

Fundamental Metabolic Divergence

The metabolism of natural progesterone differs fundamentally from that of synthetic progestins, resulting in distinct biological activity profiles. Natural progesterone undergoes extensive enzymatic transformation into active neurosteroids, while most synthetic progestins are metabolized into compounds with different receptor binding affinities or are excreted largely unchanged [1] [16].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Enzymes for Progestogens

| Enzyme | Role in Progesterone Metabolism | Role in Synthetic Progestin Metabolism |

|---|---|---|

| 5α-reductase (type 1) | Converts progesterone to 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP) | Limited activity on most synthetic progestins |

| 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) | Converts 5α-DHP to allopregnanolone (3α,5α-THPROG) | Minimal to no production of neuroactive metabolites |

| Cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4, CYP2C19) | Hepatic hydroxylation and clearance | Primary metabolism for some synthetic progestins |

| 5β-reductase | Converts progesterone to 5β-dihydroprogesterone | Activity varies by progestin structure |

Metabolism of Natural Progesterone

Natural progesterone follows two primary metabolic pathways in neural and peripheral tissues:

- The 5α-reduction pathway: Progesterone → 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP) → allopregnanolone (3α,5α-THPROG) [17] [1]

- The 5β-reduction pathway: Progesterone → 5β-dihydroprogesterone → pregnanolone [1]

These reduced metabolites, particularly allopregnanolone, function as potent positive allosteric modulators of GABA-A receptors, mediating significant neuropsychiatric effects including anxiolysis, antidepressant activity, and neuroprotection [17] [16] [18]. The expression of the requisite enzymes (5α-reductase 1, 3α-HSD) has been documented throughout the human brain, with highest concentrations in the cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala [17].

Metabolism of Synthetic Progestins

Synthetic progestins exhibit markedly different metabolic patterns:

- Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA): Undergoes limited metabolism while retaining affinity for progesterone, glucocorticoid, and androgen receptors [19] [16]

- Norethisterone (NET): Metabolized via 5α-reduction to 5α-dihydro-NET, which exhibits altered receptor binding affinity with reduced progestational but increased anti-progestational activity [20]

- Levonorgestrel (LNG) and Etonogestrel: Primarily metabolized via hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes without significant conversion to neuroactive steroids [19]

The structural modifications in synthetic progestins that enhance oral bioavailability and prolong half-life simultaneously prevent their metabolism into neuroactive compounds with GABAergic activity [16] [18].

Figure 1: Comparative Metabolic Pathways of Natural Progesterone versus Synthetic Progestins

Experimental Assessment of Progestogen Metabolism

Analytical Methodologies

Accurate assessment of progestogen metabolism requires sophisticated analytical techniques. Ultra-high performance supercritical fluid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPSFC-MS/MS) has emerged as a gold standard for simultaneously quantifying progesterone and its metabolites in biological samples [19]. This method offers superior sensitivity in the nanomolar range, capable of detecting physiological concentrations present in serum and tissue samples.

Earlier methodologies, particularly immunoassays without chromatographic separation, have significant limitations due to cross-reactivity with structurally similar metabolites, potentially overestimating progesterone concentrations by 5- to 8-fold [21]. This methodological consideration is particularly crucial when evaluating oral progesterone pharmacokinetics, where metabolite concentrations vastly exceed parent compound levels due to extensive first-pass metabolism.

Cell-Based Metabolism Studies

Table 2: Experimental Models for Progestogen Metabolism Research

| Model System | Applications | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Mammalian cell lines (HEK293T, HeLa, END-1, T47D) | Metabolism kinetics, cell-specific patterns | 50-100% of P4 metabolized within 24h; cell line- and progestin-specific metabolism [19] |

| Primary human tissue (endocervical explants) | Tissue-relevant metabolism | MPA and NET significantly metabolized, but less extensively than P4 [19] |

| Neuronal/glial cultures | Neurosteroidogenesis | Neurons show higher 5α-reductase activity; astrocytes have higher 3α-HSD activity [17] |

Experimental data demonstrates that metabolism varies significantly across cell types. In studies of nine mammalian cell lines commonly used in progesterone research, 50-100% of progesterone was metabolized within 24 hours across all cell lines [19]. The metabolism of synthetic progestins was both progestin-specific and cell line-specific, with MPA and NET being significantly metabolized in human cervical tissue, though to a lesser extent than progesterone [19].

Receptor Binding Assays

Competitive binding studies reveal substantial differences in receptor affinity profiles:

- Natural progesterone: High affinity for progesterone receptor (PR); potent antagonist of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR); weak partial agonist of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) [22] [16]

- Medroxyprogesterone acetate: Binds PR, GR, and AR with significant agonist activity at latter two receptors [16]

- Norethisterone and metabolites: Variable affinity for PR and AR depending on reduction state [20]

These differential binding profiles explain many of the distinct side effect patterns observed clinically, particularly regarding androgenic, metabolic, and neuropsychiatric effects.

Neuroactive Metabolites and Central Nervous System Effects

GABAergic Mechanisms

The neuroactive metabolites of natural progesterone, particularly allopregnanolone, function as potent positive allosteric modulators of GABA-A receptors, enhancing chloride influx and neuronal inhibition even at nanomolar concentrations [17] [16] [18]. This mechanism underlies the documented anxiolytic, antidepressant, sedative, and analgesic properties of natural progesterone and its metabolites.

Synthetic progestins, due to their structural differences, cannot be converted into GABA-active neurosteroids [16] [18]. This fundamental metabolic difference explains the divergent neuropsychiatric profiles observed in clinical practice, where synthetic progestins often lack the beneficial mood effects or may even exacerbate negative affect.

Neuroprotective Effects

Progesterone and its neuroactive metabolites demonstrate significant neuroprotective properties in experimental models of traumatic brain injury, stroke, and neurodegenerative conditions [17]. These effects are mediated through multiple mechanisms, including:

- Reduction of cerebral edema via GABA-mediated mechanisms

- Deflammation and reduction of inflammatory cytokines

- Enhancement of remyelination through oligodendrocyte precursor differentiation

- Reduction of apoptosis in vulnerable neuronal populations

The neuroprotective efficacy appears dependent on conversion to allopregnanolone, as demonstrated by the critical role of 5α-reductase inhibition in blocking these beneficial effects [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Progestogen Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Manufacturer/Source | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| UHPSFC-MS/MS system | Multiple vendors | Simultaneous quantification of progestogens and metabolites |

| HEK293T cells | ATCC | General metabolism studies; receptor signaling |

| T47D breast cancer cells | ATCC | PR-mediated gene expression; metabolism studies |

| Primary endocervical cells | Tissue procurement programs | Tissue-relevant metabolism models |

| 5α-reductase inhibitors (e.g., finasteride) | Multiple vendors | Pathway inhibition studies |

| Specific receptor antagonists (e.g., mifepristone) | Multiple vendors | Receptor mechanism studies |

| CYP450 inhibitors | Multiple vendors | Hepatic metabolism characterization |

Implications for Drug Development

The metabolic differences between natural progesterone and synthetic progestins have profound implications for pharmaceutical development:

Route of administration significantly impacts metabolic fate - oral administration yields high metabolite concentrations, while vaginal administration provides more stable progesterone levels with minimal first-pass effects [16] [21]

Individual variation in metabolic enzyme expression (e.g., 5α-reductase polymorphisms) may predict therapeutic response and side effect profiles

Therapeutic targeting of neurosteroidogenesis represents a promising avenue for mood disorder treatment, as demonstrated by the FDA approval of brexanolone (allopregnanolone) for postpartum depression [18]

Future research should focus on developing novel progestins capable of metabolism into neuroactive compounds while maintaining favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles.

Bioavailability and the Rationale for Micronization

In pharmaceutical development, bioavailability is a critical determinant of therapeutic efficacy, particularly for poorly soluble active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). It is estimated that over 30% of today's APIs, and approximately 90% of new chemical entities (NCEs), fall into the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) class II or IV, characterized by poor water solubility [23] [24]. For these compounds, dissolution rate in the gastrointestinal fluid becomes the rate-limiting step for absorption, ultimately restricting their bioavailability [23]. To overcome this fundamental challenge, particle size reduction through micronization has emerged as a foundational technological strategy. This process, which produces particle size distributions typically below 10 microns, significantly increases the surface area available for dissolution, thereby enhancing dissolution rate and improving oral bioavailability [23] [25]. This article examines the scientific rationale for micronization, with a specific focus on its application to hormones like progesterone, and provides a comparative analysis of the bioavailability and safety profiles of micronized progesterone versus synthetic progestins.

The Micronization Process: Techniques and Strategic Advantages

Micronization is a particle engineering technique designed to produce fine API particles with a specific size distribution. The term "micronization" generally refers to processes yielding a particle size distribution where the D90 is below 40–50 µm, distinguishing it from "fine milling" (D90 between 50–100 µm) and standard "milling" (D90 > 100 µm) [25]. The selection of technology depends on the target Particle Size Distribution (PSD) and the API's physical and chemical properties.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Micronization Technologies

| Technology | Target PSD | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spiral Jet Mill | Fine, narrow PSD (D90 < 40-50 µm) | No moving parts, reduced energy consumption, simpler processes, higher yields [25]. | Risk of generating partially amorphous powder; can produce broader PSD for low-potency APIs [25]. |

| Opposite Jet Mill | Controlled top size | Greater control over the top particle size via a classifier wheel [25]. | More complex systems with larger contact surfaces; potential for clogging [25]. |

| Mechanical Milling | Coarser PSDs | More homogeneous powders at higher PSD values; better powder flowability; simpler processes [25]. | Risk of overheating and abrasion; more complicated process temperature control [25]. |

| Wet Mill | Nano-size | Can be combined with the final crystallization step [25]. | Risk of agglomerated powder during subsequent filtration and drying [25]. |

| Spray Dry | Spherical, amorphous particles | Produces spherical particles with better flowability [25]. | Higher cost and environmental impact; lower yields [25]. |

| In Situ Micronization | Micron-sized crystals | One-step process during crystallization; no external mechanical force; uses common equipment; homogeneous PSD with reduced agglomeration [23]. | Requires specific crystallization setup and stabilizing agents [23]. |

A key advancement in this field is in situ micronization. Unlike traditional techniques that apply external forces to reduce the size of pre-formed large crystals, in situ micronization produces micron-sized crystals directly during the crystallization process itself [23]. This one-step process requires only mild agitation and common equipment, avoiding the need for specialized, expensive containment facilities [23]. A critical benefit of in situ micronization is the ability to perform simultaneous surface modification by adding hydrophilic polymers (e.g., HPMC, PVP) during crystallization. These stabilizers adsorb onto the newly formed crystal surfaces, sterically inhibiting crystal growth and particle agglomeration, which results in a more homogeneous PSD and improved powder stability [23].

Rationale for Micronizing Progesterone: Enhancing Bioavailability

The micronization of progesterone is a practical and critical application of these principles. Natural progesterone, when not micronized, suffers from very low oral bioavailability due to its poor solubility in aqueous environments [16] [26]. This limitation was the primary driver for the historical development of synthetic progestins, which were structurally modified to improve metabolic stability and absorption [27] [28].

The scientific basis for micronizing progesterone is grounded in the Noyes-Whitney equation, which describes the dissolution rate of a solid in a liquid medium. The equation states that the dissolution rate (dC/dt) is proportional to the surface area (A) available for dissolution, the diffusion coefficient (D), and the concentration gradient (C_s - C), and inversely proportional to the diffusion layer thickness (h).

Dissution Rate = (A * D * (C_s - C)) / h

By reducing the particle size, micronization dramatically increases the surface area (A), thereby directly enhancing the dissolution rate. This increased dissolution is the key mechanism that improves the absorption of progesterone from the gastrointestinal tract into the bloodstream, making it a viable oral drug [23].

It is crucial to distinguish between pharmaceutical-grade micronized progesterone and compounded "bioidentical" products. Regulated micronized progesterone (e.g., FDA/EMA-approved) is a standardized pharmaceutical with proven bioavailability, efficacy, and safety profiles [27] [28]. In contrast, compounded preparations are not subject to the same rigorous quality control, leading to concerns about their purity, potency, and consistency [28].

Diagram 1: Mechanism of Micronization-Enhanced Bioavailability. This workflow illustrates the causal pathway from particle size reduction to therapeutic efficacy.

Comparative Analysis: Micronized Progesterone vs. Synthetic Progestins

The fundamental difference between micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins lies in their chemical structure and origin. Micronized progesterone (P4) is bioidentical—its molecular structure is identical to the progesterone produced by the human corpus luteum [27] [16] [28]. Synthetic progestins, on the other hand, are structurally modified molecules designed to enhance oral bioavailability and metabolic stability [27] [28]. This structural difference dictates their distinct pharmacodynamic, safety, and clinical profiles.

Pharmacodynamic and Receptor Binding Profiles

The safety and side-effect profiles of different progestogens are largely determined by their affinity for non-progesterone receptors.

Table 2: Receptor Binding and Off-Target Effects of Progestogens [27] [28]

| Progestogen | Androgenic | Anti-androgenic | Glucocorticoid | Anti-mineralocorticoid | Key Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone (P4) | - | (+) | + | + | Neutral or beneficial metabolic effects; minimal androgenic side effects [27]. |

| Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) | (+) | - | + | - | Associated with increased breast cancer risk and unfavorable metabolic effects in WHI study [27] [28]. |

| Levonorgestrel (LNG) | + | - | - | - | Can cause androgenic side effects like acne and weight gain [26] [29]. |

| Norethisterone | + | - | - | - | Androgenic side effects are possible [26]. |

| Drospirenone (DRSP) | - | + | ? | + | Can help reduce blood pressure and fluid retention [30] [28]. |

| Dienogest | - | + | - | - | Suitable for women with acne or hirsutism [28]. |

| Dydrogesterone (DYD) | - | - | ? | (+) | Minimal impact on metabolic parameters [28]. |

Key: ++ = strongly effective, + = effective, (+) = weakly effective, - = ineffective, ? = unknown.

A critical pharmacodynamic distinction is the activity of progesterone and its metabolites in the central nervous system. Progesterone and its metabolite, allopregnanolone, are positive allosteric modulators of the GABA_A receptor [16]. This mechanism explains the anxiolytic, antidepressant, and sedative effects of oral micronized progesterone, which are not observed with synthetic progestins [16]. In fact, some synthetic progestins have been linked to negative mood effects [29].

Safety and Efficacy in Clinical Applications

Clinical data, particularly from hormone replacement therapy (HRT), reveals significant safety differences.

Table 3: Comparative Clinical Profiles in Hormone Replacement Therapy

| Parameter | Micronized Progesterone (P4) | Synthetic Progestins (e.g., MPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Endometrial Protection | Effective (≥200 mg for 10-14 days/month prevents hyperplasia) [28]. | Effective and potent for endometrial protection [27]. |

| Breast Cancer Risk | Lower risk profile; associated with a lower or neutral risk in studies [27] [28]. | Higher risk; MPA in the WHI study showed increased risk [27] [26]. |

| Cardiovascular Risk | More favorable profile; neutral or beneficial effect on lipids; lower risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) [27] [28]. | Less favorable; certain progestins can increase VTE risk and have negative metabolic effects [27] [26]. |

| Mental Health & Mood | Favorable; metabolites have calming, sedative effects via GABA_A receptor [16]. | Variable; some progestins (e.g., Levonorgestrel) can negatively impact mood and are linked to higher antidepressant use [29]. |

| Metabolic Effects | Relatively neutral or beneficial influence on metabolic parameters [27]. | Heterogeneous; some androgenic progestins can negatively impact lipid profiles [28]. |

The landmark Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study, which used conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), reported increased risks of breast cancer and cardiovascular events, leading to a global decline in HRT use [27] [28]. Subsequent research has clarified that these risks are not a "class effect" for all progestogens. Regimens using micronized progesterone have demonstrated a significantly safer profile, particularly concerning breast cancer and cardiovascular risks [27] [26] [28].

Diagram 2: Differential Receptor Binding of Progesterone vs. Progestins. This diagram highlights the more targeted receptor profile of micronized progesterone compared to the broader, off-target binding of many synthetic progestins.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

For researchers investigating the bioavailability and performance of micronized progesterone, several key reagents and materials are essential.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Micronized Progesterone Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Research Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Micronized Progesterone API | The active pharmaceutical ingredient with reduced particle size (D90 < 50 µm). | Source a GMP-grade API with a well-characterized PSD (D10, D50, D90) and known crystalline form. |

| Stabilizing Agents (HPMC, PVP) | Prevent agglomeration and crystal growth; improve powder stability and flow [23]. | Use during in situ micronization or post-milling conditioning. HPMC is often preferred for its effective stabilization of hydrophobic surfaces [23]. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | To measure the dissolution rate under physiologically relevant conditions. | Use USP-compliant FaSSGF/FeSSGF and FaSSIF/FeSSIF media to predict in vivo performance. |

| Hydrophilic Excipients (Lactose, Mannitol) | Act as diluents and carriers in formulation, aiding in content uniformity and flow. | Critical for formulating high-potency APIs where the micronized drug is a small fraction of the blend [25]. |

| Inert Milling Gas (Nitrogen) | Prevents oxidation and controls thermal effects during high-energy milling processes [25]. | Essential for jet milling of oxygen- or heat-sensitive APIs to maintain chemical and solid-state stability. |

Micronization is a foundational and strategic tool in modern drug development, effectively overcoming the bioavailability hurdles inherent in poorly soluble APIs like natural progesterone. The process transforms progesterone from a therapeutically non-viable oral drug into a bioavailable pharmaceutical agent. The comparative analysis reveals that while synthetic progestins were created to solve the bioavailability issue and remain highly effective for contraception, micronized progesterone offers a distinct and often superior safety profile, especially for long-term menopausal hormone therapy. Its bioidentical structure, favorable receptor binding profile, and neutral or beneficial metabolic and cardiovascular effects position it as a preferred option in clinical scenarios where safety is a primary concern. The distinct pharmacodynamic properties of micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins confirm that they do not belong to a single pharmacological class and should be selected based on individualized risk-benefit assessment.

Clinical Applications and Route-Specific Pharmacokinetics

Formulations and Approved Clinical Indications

Progestogens, compounds that exhibit progestational activity, are broadly categorized into two distinct classes: natural progesterone and synthetic progestins. Synthetic progestins are artificial molecules designed to mimic the effects of natural progesterone, and they are further classified by their generation or structural properties into pregnanes, estranes, and gonanes [4]. Micronized progesterone (MP), first synthesized in 1984, is a natural progesterone formulation where the hormone particle size is mechanically reduced (micronized) to significantly enhance its oral bioavailability, overcoming the poor absorption and rapid metabolic decay that previously limited the therapeutic use of natural progesterone [1]. A critical concept in this field is that a class effect does not exist for these compounds; micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins possess distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles, leading to different efficacy and safety outcomes in clinical use [16]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of their formulations, approved indications, and underlying mechanisms.

Formulations and Pharmacodynamic Profiles

Available Formulations and Structural Classes

Table 1: Classification and Formulations of Progestogens

| Category | Subclass / Derivation | Example Agents | Common Formulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Progesterone | N/A | Micronized Progesterone (Prometrium) [5] | Oral Capsule (100 mg, 200 mg) [5], Vaginal Gel [5] |

| Synthetic Progestins | Pregnanes (derived from progesterone) | Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (Provera, Cycrin), Nomegestrol Acetate [4] | Tablet, Intramuscular/Subcutaneous Injection [4] [5] |

| Estranes (derived from testosterone; more androgenic) | Norethindrone, Norethindrone Acetate [4] | Tablet [5] | |

| Gonanes (derived from testosterone; less androgenic) | Levonorgestrel, Desogestrel, Norgestimate [4] | Tablet, Subcutaneous Implant, Intrauterine Device (IUD) [4] |

Receptor Binding and Signaling Pathways

The fundamental differences in safety and efficacy between micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins stem from their distinct interactions with steroid receptors. These agents exert their primary effects by binding to the genomic progesterone receptor (PR), but they have vastly variable affinities for other steroid receptors, leading to a range of off-target effects [16].

Diagram: Progestogen Signaling Pathways and Receptor Interactions

Key mechanistic differences include [16]:

- Micronized Progesterone: Acts as a weak agonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and, through its metabolite allopregnanolone, is a positive modulator of the GABA-A receptor. This GABAergic activity explains its neuroprotective and psychopharmacological effects, such as drowsiness, anxiolysis, and antidepressant properties.

- Synthetic Progestins: Many synthetic progestins, particularly those derived from testosterone (estranes and gonanes), act as partial to full agonists of the androgen receptor (AR), leading to potential side effects like acne, hirsutism, and adverse lipid changes. Some also have significant glucocorticoid receptor (GR) activity, which can cause salt and water retention [16].

Approved Clinical Indications and Comparison of Efficacy

Table 2: Approved Clinical Indications for Micronized Progesterone and Select Synthetic Progestins

| Indication | Micronized Progesterone | Synthetic Progestins (Examples) |

|---|---|---|

| Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) | Approved for postmenopausal HRT in combination with estrogen [31] [5]. | Approved (e.g., Medroxyprogesterone Acetate, Norethindrone Acetate) [4] [5]. |

| Amenorrhea | Approved for treatment of secondary amenorrhea [31] [5]. | Approved (e.g., Medroxyprogesterone Acetate) [5]. |

| Contraception | Not typically used for contraception. | Approved in various forms: Combination oral contraceptives, progestin-only pills, implants, IUDs, injectables [4]. |

| Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding | Used for treatment [31] [5]. | Used for treatment (e.g., Medroxyprogesterone Acetate) [5]. |

| Luteal Phase Support | Used in Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) after embryo transfer [4] [16]. | Not the primary choice for this indication. |

| Prevention of Preterm Birth | Used to prevent preterm labor in at-risk women [4] [16]. | Not the primary choice for this indication. |

| Endometrial Hyperplasia | Demonstrated efficacy in treatment [32] [1]. | Used for treatment (e.g., Lynestrenol, Medroxyprogesterone Acetate) [32]. |

Comparative Efficacy in Key Indications

Treatment of Endometrial Hyperplasia

A direct comparison of efficacy is illustrated in a 2014 randomized controlled trial by Tasci et al., which compared micronized progesterone and the synthetic progestin lynestrenol for treating simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia [32].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: To evaluate the regression/resolution rates of simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia after treatment with different progestagens.

- Population: 60 premenopausal women with histologically confirmed endometrial hyperplasia without atypia.

- Intervention: Patients were randomized into two groups:

- Group I (n=30): Received lynestrenol 15 mg/day.

- Group II (n=30): Received micronized progesterone 200 mg/day.

- Treatment Duration: Both treatments were administered for 12 days per cycle over 3 months.

- Outcome Measurement: Endometrial curettage was performed after 3 months to assess histological regression, resolution, or persistence.

Results: The study concluded that lynestrenol was more effective at inducing endometrial resolution compared to micronized progesterone (p=0.045), a difference that was particularly significant in patients over 45 years of age (p=0.036). However, no cases in either group experienced disease progression [32].

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) and Safety Profile

In the context of HRT, the choice of progestogen is critical for mitigating the risk of endometrial cancer caused by unopposed estrogen in women with a uterus. While both micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins are effective for this purpose, their long-term safety profiles differ.

The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study, which primarily used the synthetic progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) in combination with conjugated equine estrogen, reported an increased risk of breast cancer. Subsequent analyses suggest this risk may be specific to MPA and not applicable to estrogen-only therapy or potentially to micronized progesterone [33]. Micronized progesterone has a better safety profile regarding breast cancer risk, venous thromboembolism, and metabolic ailments compared to many synthetic progestins, making it the preferred option for women with increased cardiovascular or metabolic risk factors [1] [16].

Furthermore, the FDA has recently moved to remove the longstanding "black box" warnings regarding cardiovascular and breast cancer risks from HRT products, reflecting an updated understanding of the risks based on factors like a woman's age and time since menopause, as well as the type of hormones used [33] [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Key Reagents and Models for Progestogen Research

| Reagent / Model | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines Expressing Steroid Receptors | In vitro models to study receptor binding affinity, transcriptional activation, and cell-specific responses. | Characterizing the androgenic or glucocorticoid activity of novel synthetic progestins [16]. |

| Animal Models (e.g., rodent) | In vivo models to study systemic effects, including on the endometrium, cardiovascular system, brain, and bone. | Investigating the neuroprotective effects of progesterone and allopregnanolone [16]. |

| Progesterone Receptor (PR) Antagonists | Tools to block PR signaling and confirm the receptor-specificity of observed effects. | Validating that a particular endometrial effect is mediated through the classical PR pathway. |

| Enzyme Immunoassays (EIA) / LC-MS | Precise quantification of progesterone, its metabolites (e.g., allopregnanolone), and synthetic progestins in biological fluids. | Pharmacokinetic studies to determine bioavailability and half-life of different formulations [1]. |

| Human Endometrial Tissue Cultures | Ex vivo models to study the direct effects of progestogens on endometrial proliferation, decidualization, and gene expression. | Comparing the molecular pathways activated by micronized progesterone vs. synthetic progestins in the human endometrium. |

Impact of Administration Route on Efficacy and Safety

The choice of administration route is a critical determinant in the therapeutic profile of progestogens, significantly impacting their efficacy, safety, and patient compliance. Within the context of a broader thesis on the comparative safety profile of micronized progesterone versus synthetic progestins, this guide provides a systematic comparison framed for researchers and drug development professionals. A comprehensive understanding of how administration routes—ranging from oral and vaginal to subcutaneous and transdermal—influence pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics is essential for optimizing therapeutic strategies and developing next-generation formulations. This analysis synthesizes current clinical evidence and experimental data to objectively compare the performance of these agents, with a focus on their implications for clinical practice and future research.

Pharmacological Fundamentals: Micronized Progesterone vs. Synthetic Progestins

Defining Molecular Identity and Origin

The fundamental distinction between these agents lies in their chemical structure and origin. Micronized progesterone is a bioidentical hormone, meaning its molecular structure is identical to the endogenous progesterone produced by the human corpus luteum. It is typically synthesized from plant sterols (e.g., diosgenin from wild yams or soy) and undergoes a micronization process that reduces particle size to enhance its absorption and bioavailability [35]. In contrast, synthetic progestins (e.g., levonorgestrel, desogestrel, medroxyprogesterone acetate) are engineered molecules designed to mimic progesterone's activity but with altered chemical structures. These modifications aim to improve oral absorption, increase receptor binding affinity, or extend half-life, but they also lead to distinct off-target effects and safety profiles [35].

Mechanisms of Action and Receptor Interactions

Both classes bind to the intracellular progesterone receptor (PR), but their subsequent interactions diverge significantly. Micronized progesterone elicits a native hormonal response that closely resembles physiological signaling. Synthetic progestins, however, can engage with a wider range of steroid hormone receptors due to their structural differences. Their activity profiles are diverse: some exhibit androgenic properties (e.g., levonorgestrel), while others are anti-androgenic (e.g., drospirenone) or possess glucocorticoid activity. These divergent receptor interactions are primarily responsible for their differing side effect and risk profiles [35]. The metabolism of these compounds also varies; micronized progesterone is rapidly metabolized by the liver when taken orally, whereas many synthetic progestins are designed to resist first-pass metabolism, allowing for lower dosing but sometimes introducing unique metabolic consequences [36].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Micronized Progesterone and Synthetic Progestins

| Characteristic | Micronized Progesterone | Synthetic Progestins |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Bioidentical to human progesterone | Synthetically modified variants |

| Origin | Synthesized from plant sterols | Fully synthetic |

| Primary Mechanism | Activation of native progesterone receptors | Activation of progesterone receptors, with varying affinities for other steroid receptors |

| Metabolic Profile | Rapid oral metabolism; avoids first-pass via non-oral routes | Often engineered to resist first-pass metabolism; metabolism varies by type |

| Common Examples | Oral (Prometrium), Vaginal gel (Crinone) | Levonorgestrel (LNG), Desogestrel (DSG), Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA), Drospirenone (DRSP) |

Comparative Analysis of Administration Routes

Efficacy and Safety Across Indications

The administration route directly influences drug bioavailability, peak concentration time, and tissue-specific distribution, thereby shaping the therapeutic outcome.

Menopause Therapy: In hormone replacement therapy (HRT), the combination with estrogen requires a progestogen to protect the endometrium in women with a uterus. Oral micronized progesterone is associated with a superior safety profile, including a lower risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular events compared to older synthetic progestins like medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) [35] [36]. Transdermal systems (patches, gels) that deliver synthetic progestins offer the advantage of bypassing first-pass hepatic metabolism, which avoids the undesirable increase in sex hormone-binding globulin and may reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared to oral routes [36].

Fertility and Pregnancy Support: The vaginal route is paramount for micronized progesterone in supporting assisted reproduction and maintaining early pregnancy. Vaginal administration (e.g., 400 mg twice daily) achieves high local uterine tissue concentrations with lower systemic levels, a phenomenon known as "uterine first-pass effect", which is ideal for endometrial priming without significant systemic side effects [37]. Large, high-quality trials like the PRISM and PROMISE studies demonstrated that vaginal micronized progesterone significantly increases live birth rates in women with early pregnancy bleeding and a history of recurrent miscarriages [37]. Synthetic progestins are less commonly used for this indication due to potential receptor mismatch and teratogenic concerns.

Contraception: Synthetic progestins dominate this field due to their potent and reliable suppression of ovulation. Administration routes are diverse, including oral pills (e.g., desogestrel), subdermal implants (etonogestrel), intrauterine systems (levonorgestrel-IUD), and injections (MPA). The localized delivery via IUDs minimizes systemic side effects while providing excellent endometrial suppression [35]. Micronized progesterone is not used for contraception because it is less effective at suppressing ovulation.

Table 2: Impact of Administration Route on Key Clinical Outcomes

| Indication & Route | Key Efficacy Findings | Major Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Menopause (Oral) | Effective endometrial protection with estrogen. | Micronized progesterone has lower breast cancer & CVD risk vs. synthetic MPA [35]. Oral estrogen increases VTE risk [36]. |

| Menopause (Transdermal) | Effective endometrial protection and VMS relief. | Bypasses first-pass liver metabolism; may reduce VTE risk compared to oral [36]. |

| Fertility (Vaginal) | Increases live birth rate in women with recurrent miscarriage and early pregnancy bleeding (72% vs 57% with placebo in high-risk subgroup) [37]. | Excellent local efficacy with minimal systemic side effects (e.g., drowsiness). |

| Contraception (Oral/IUD) | Highly effective ovulation suppression (progestins). LNG-IUD provides local endometrial action. | Systemic progestins: androgenic effects (acne). LNG-IUD: localized side effects (spotting). |

Safety and Adverse Event Profiles

The route of administration is a critical modifier of a drug's adverse event (AE) profile.

Systemic vs. Local Effects: Oral administration often leads to a higher incidence of systemic AEs. For micronized progesterone, these include drowsiness and dizziness due to the sedating neurosteroid metabolites produced during first-pass liver metabolism [35]. For synthetic progestins, oral intake can lead to androgenic side effects like acne and mood swings, particularly with first- and second-generation compounds [35]. In contrast, local administration (e.g., vaginal progesterone, levonorgestrel-IUD) largely confines effects to the target tissue, minimizing systemic exposure and associated AEs. Common AEs for these routes are local, such as vaginal discharge or irritation, and initial spotting with the IUD [35].

Long-Term Risks: Landmark studies like the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) highlighted that the long-term use of specific synthetic progestins (namely MPA) in combination with oral estrogen was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer and stroke [35]. Subsequent research indicates that micronized progesterone does not carry the same level of risk for these serious AEs, making it a safer option for long-term HRT [35] [36]. The choice of administration route can further modulate these risks, as non-oral estrogen (often paired with a progestogen) appears to mitigate the VTE risk associated with oral estrogen therapy [36].

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Key Clinical Trials and Protocols

Robust, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the highest level of evidence for comparing therapeutic options.

The PRISM and PROMISE Trials:

- Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of vaginal micronized progesterone in preventing miscarriage in women with early pregnancy bleeding (PRISM) and in women with unexplained recurrent miscarriages (PROMISE) [37].

- Methodology: Both were large, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs. In the PRISM trial, 4153 women with early pregnancy bleeding were randomized to receive either 400 mg micronized progesterone vaginally twice daily or a matching placebo, from presentation until 16 weeks of gestation [37].

- Outcome Measures: The primary outcome was live birth after 34 weeks. Prespecified subgroup analysis was critical, revealing that benefit increased with the number of previous miscarriages. For women with ≥3 miscarriages and bleeding, the live birth rate was 72% with progesterone vs. 57% with placebo (Rate Difference 15%) [37].

Network Meta-Analysis on Contraceptives:

- Objective: To compare the effectiveness and safety of different progestins in combined oral contraceptives (COCs), including gestodene (GSD), desogestrel (DSG), drospirenone (DRSP), and levonorgestrel (LNG) [30].

- Methodology: A systematic review and network meta-analysis (NMA) of 18 RCTs. Statistical analysis involved estimating odds ratios (ORs) and using surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) to rank treatments for outcomes like breakthrough bleeding (BTB) and adverse events [30].

- Key Findings: GSD demonstrated the lowest incidence of BTB (OR 0.41), while DRSP had the most favorable safety profile (lowest adverse event rate). Contraceptive efficacy was comparable across all progestins [30].

The workflow below illustrates the design and key findings of the PRISM trial.

Signaling Pathways and Pharmacodynamic Interactions

The differential effects of micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins can be traced to their distinct interactions at the molecular and cellular level. Micronized progesterone binds almost exclusively to the progesterone receptor (PR), leading to genomic actions that modulate gene transcription in a physiological manner. Synthetic progestins, due to their altered structures, not only activate the PR but also exhibit cross-reactivity with other steroid receptors, including androgen (AR), glucocorticoid (GR), and mineralocorticoid (MR) receptors. This promiscuous receptor binding is the primary driver of their non-progestogenic side effects, such as the androgenic acne associated with levonorgestrel or the anti-mineralocorticoid effects of drospirenone.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting research in progestogen pharmacology and drug delivery.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Progestogen Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Micronized Progesterone | The reference standard for bioidentical activity; used in in vitro and in vivo studies to establish a baseline for native PR activation and signaling. |

| Synthetic Progestins (LNG, DSG, DRSP, MPA) | Critical for comparative studies investigating receptor binding affinity, selectivity, and off-target pharmacological effects. |

| Cell Lines Expressing Human PR | Engineered cell lines (e.g., T47D) are fundamental for in vitro assays to study PR-mediated gene expression, cell proliferation, and drug efficacy. |

| Animal Models (Ovariectomized Rodents) | Standard preclinical models for studying the endometrial protective effects, metabolic impact, and central nervous system effects of various progestogen formulations. |

| HPLC-MS/MS Systems | Essential for analytical quantification of drug and metabolite concentrations in plasma and tissues for robust pharmacokinetic (PK) studies. |

| Simulated Vaginal Fluid | Used in dissolution testing to evaluate the release kinetics and stability of vaginal formulations like gels and suppositories. |

The administration route is an indispensable variable that profoundly shapes the efficacy, safety, and overall clinical utility of both micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins. The evidence demonstrates that micronized progesterone, particularly via the vaginal route, is the cornerstone for fertility and pregnancy support, offering targeted efficacy with minimal systemic side effects. In menopause management, oral micronized progesterone presents a more favorable safety profile concerning breast cancer and cardiovascular risks compared to many synthetic alternatives. Conversely, synthetic progestins, delivered via a versatile array of routes from oral to intrauterine, remain dominant in contraception due to their potent anti-ovulatory action. The trend in drug development is moving towards localized delivery systems and the refinement of synthetic molecules with cleaner receptor profiles. Future research should continue to leverage high-quality RCTs and sophisticated meta-analyses to further elucidate the complex interplay between drug, delivery route, and patient-specific factors, ultimately enabling more personalized and effective hormone therapies.

The Role of Micronized Progesterone in Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT)

In menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), progestogens are essential for endometrial protection in women with a uterus who are receiving estrogen. However, not all progestogens are the same. The progestogen class includes both synthetic progestins and natural progesterone, known as P4 [16]. Micronized progesterone (specifically, oral micronized progesterone) is a bioidentical hormone with a molecular structure identical to the endogenous progesterone produced by the human ovaries [38] [39]. Its development addressed the poor oral absorption of natural progesterone [39].

A fundamental concept confirmed by modern research is that a single class effect does not exist for micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins; they have distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics, leading to different efficacy and safety profiles [16]. This review compares the performance and safety of micronized progesterone against synthetic progestins within the context of MHT.

Molecular and Functional Comparison

Structural and Receptor Binding Differences

The core difference lies in their origin and structure. Micronized progesterone is bioidentical to human progesterone, while synthetic progestins are chemically modified variants [16] [39]. These structural differences result in significantly different binding affinities for various steroid receptors, which explains their divergent side effect profiles [16].

Table 1: Key Structural and Origin Differences.

| Characteristic | Micronized Progesterone | Synthetic Progestins |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Identical to human progesterone | Chemically modified |

| Origin | Synthesized from plant sterols (e.g., diosgenin from wild yams) | Fully synthesized in laboratories |

| "Bioidentical" Status | Yes | No |

Receptor Affinity and Downstream Effects

The variable affinity for steroid receptors is a primary driver of clinical differences. Synthetic progestins often have affinity for other steroid receptors, leading to androgenic, glucocorticoid, or anti-mineralocorticoid side effects absent with micronized progesterone [16].

Table 2: Comparative Receptor Binding and Clinical Implications.

| Receptor / Activity | Micronized Progesterone | Synthetic Progestins (e.g., MPA, Norethindrone) | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone Receptor (PR) | Natural agonist [16] | Agonist (high affinity) [16] | Both provide endometrial protection. |

| Androgen Receptor (AR) | No significant affinity [16] | Variable affinity; some are agonists (e.g., MPA, Norethindrone) [16] | Androgenic progestins linked to acne, hirsutism, and unfavorable lipid changes [16]. |

| Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) | No significant affinity [16] | Agonist activity (e.g., MPA) [16] | Associated with glucocorticoid-like effects such as weight gain [16]. |

| Mineralocorticoid Receptor (MR) | Antagonist [16] | No significant activity [16] | P4 may have a mild anti-mineralocorticoid effect. |

| GABAA Neurosteroid Activity | Positive allosteric modulator (via metabolites) [16] | No significant activity [16] | Explains P4's sedative, anxiolytic, and hypnotic effects [16]. |

Receptor Binding Profiles: A comparison of the primary binding interactions for micronized progesterone and synthetic progestins, highlighting the unique neuroactive properties of P4 and the off-target receptor activities of synthetic progestins.

Comparative Safety Profiles: Key Clinical Data

The distinct pharmacodynamics translate into different clinical risk profiles, particularly for breast cancer and cardiovascular events.

Breast Cancer Risk

The type of progestogen used in combined MHT significantly influences breast cancer risk. Landmark studies like the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) found that the use of conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) with the synthetic progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) was associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of breast cancer diagnosis [40] [41]. In contrast, subsequent research indicates that the risk profile associated with micronized progesterone is more favorable [42] [39].

Table 3: Comparative Breast Cancer Risk in MHT.

| MHT Regimen | Associated Breast Cancer Risk | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen alone | Not linked to increased risk; may lower risk in some groups [41]. | Women's Health Initiative (WHI) studies [41]. |

| Estrogen + Synthetic Progestin (e.g., MPA) | Increases risk, especially with >5 years of use [41]. | WHI initial findings (CEE+MPA) [42] [41]. |

| Estrogen + Micronized Progesterone | More favorable profile; lower risk marker compared to synthetic progestins [43] [39]. | UK studies and subsequent re-analyses [43]. |

Cardiovascular and Thrombotic Risk

The route of estrogen administration is a major factor in thrombotic risk, but the choice of progestogen also contributes to the overall cardiovascular risk profile.

Table 4: Cardiovascular and Thrombotic Risk Profile Comparison.

| Risk Factor | Micronized Progesterone | Synthetic Progestins (e.g., MPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) | Lower risk when combined with transdermal estrogen [44]. | Higher risk, particularly with oral estrogen regimens [44]. |

| Stroke | More favorable profile [39]. | Associated with greater risk (e.g., in WHI with CEE+MPA) [39]. |

| Lipid Metabolism | Neutral or beneficial effect on lipid profile [16]. | Androgenic progestins can adversely affect lipid metabolism [16]. |

Experimental Protocols and Key Research Reagents

For researchers investigating the differential effects of progestogens, understanding the methodologies from key studies is essential.

Receptor Binding Assay Protocol

This protocol is fundamental for characterizing the affinity and activity of novel progestogens.

Methodology:

- Cell Line: Use engineered cell lines (e.g., HeLa, COS-1) stably or transiently transfected with expression vectors for human progesterone receptor (PR), androgen receptor (AR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR).

- Ligand Preparation: Prepare test compounds (Micronized Progesterone, MPA, Norethindrone) in appropriate solvent controls. Radiolabeled reference ligands (e.g., [3H]-R5020 for PR) are required for competitive binding.

- Binding Reaction: Incubate whole cells or cell cytosolic extracts with a constant concentration of the radiolabeled ligand and increasing concentrations of the unlabeled test compound for a set period at a defined temperature.

- Separation and Measurement: Separate bound from free ligand using charcoal-dextran adsorption or filtration. Quantify the radioactivity in the bound fraction using a scintillation counter.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the inhibitory concentration 50 (IC50) for each test compound. The relative binding affinity (RBA) is determined as (IC50 of reference / IC50 of test) × 100.

Clinical Trial Design for Cardiovascular Endpoints

The "gold-standard" design for evaluating MHT safety is the randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Methodology (Modeled on WHI and subsequent RCTs):

- Population: Enroll postmenopausal women (e.g., aged 50-79) with an intact uterus. Stratify by age and time since menopause onset (e.g., <10 years vs. ≥10 years).

- Intervention: Randomize participants to:

- Group 1: Transdermal 17β-estradiol + Micronized Progesterone (200 mg/day, continuous or sequential).