Methodological Approaches for Studying Transgenerational Effects of Hormone Modulation: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

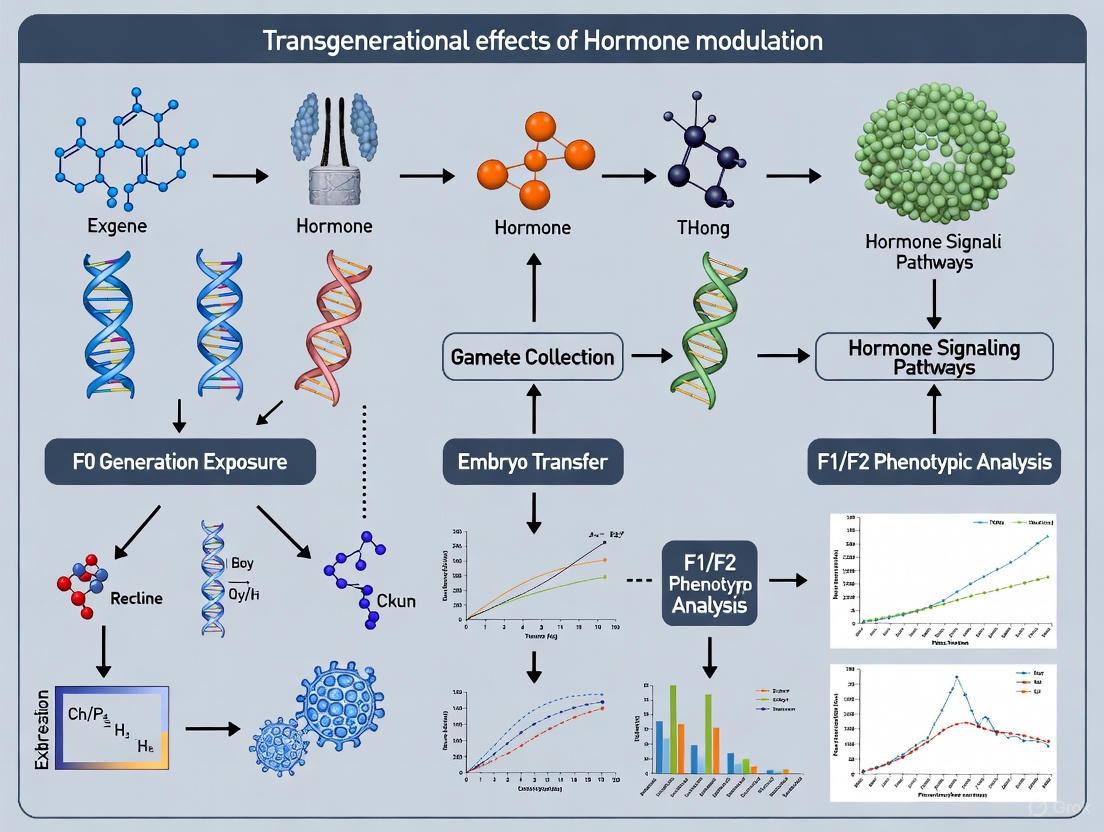

This article provides a comprehensive methodological framework for researchers and drug development professionals investigating the transgenerational inheritance of phenotypes induced by hormone-modulating agents.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Transgenerational Effects of Hormone Modulation: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive methodological framework for researchers and drug development professionals investigating the transgenerational inheritance of phenotypes induced by hormone-modulating agents. We synthesize current scientific understanding, detailing robust experimental designs to distinguish true transgenerational effects from multigenerational exposures, with a focus on endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) as model compounds. The content explores cutting-edge techniques for profiling epigenetic marks in germ cells and somatic tissues, addresses critical challenges in confounder control and data interpretation in human studies, and outlines rigorous validation strategies. By integrating foundational principles with advanced applications and troubleshooting, this guide aims to equip scientists with the tools necessary to advance this complex and rapidly evolving field, with significant implications for toxicology risk assessment and precision medicine.

Core Concepts and Evidence: Establishing the Basis for Transgenerational Inheritance

The accurate differentiation between transgenerational and multigenerational inheritance is a fundamental prerequisite in developmental and toxicological research, particularly in studies investigating the heritable effects of environmental exposures such as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). These terms are often used interchangeably in scientific literature, yet they describe fundamentally distinct biological phenomena with critical implications for experimental design and data interpretation. Multigenerational inheritance encompasses exposures that affect multiple generations simultaneously because they were directly exposed to the initial stimulus, while transgenerational inheritance requires the transmission of phenotypic or epigenetic information to generations that were never directly exposed to the original environmental insult [1] [2].

This distinction becomes particularly critical in the context of hormone modulation research, where chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and vinclozolin can induce epigenetic modifications in germ cells, potentially leading to inherited disease susceptibilities across multiple generations [2] [3]. The proper classification of these inheritance patterns directly impacts the interpretation of a compound's ability to permanently alter the germline epigenome versus causing temporary physiological effects on directly exposed tissues. Furthermore, understanding these mechanisms is essential for drug development professionals assessing the long-term safety profiles of pharmaceutical agents and their potential for inducing heritable epigenetic changes.

Table 1: Key Definitions in Inheritance Research

| Term | Definition | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Intergenerational Effects | Effects lasting 1-2 generations; the parent's environment affects their offspring [4]. | Direct exposure of the germ cells or developing embryo to the environmental stimulus. |

| Multigenerational Effects | Effects seen in generations that were directly exposed to the original stimulus (F0, F1, and F2 in maternal exposure) [1]. | Multiple generations experience direct exposure simultaneously. |

| Transgenerational Effects | Effects observed in generations that had no direct exposure to the original stimulus (F3 and beyond in maternal exposure; F2 and beyond in paternal exposure) [4] [1]. | Transmission occurs without direct exposure, implying permanent germline modification. |

Critical Distinctions and Biological Significance

Defining the Generational Boundary

The operational definitions of transgenerational and multigenerational inheritance are intrinsically linked to the developmental timing of germ cell formation and the route of exposure. In experimental models, this distinction is primarily determined by whether the genetic material for subsequent generations was present at the time of exposure [4]. When a pregnant female (designated as the F0 generation) is exposed to an environmental stimulus, three generations are simultaneously exposed: the F0 mother herself, the F1 offspring developing in utero, and the F2 germline within the developing F1 offspring [1] [2]. Consequently, effects observed in the F0, F1, and F2 generations following maternal exposure are considered multigenerational, as all these generations experienced direct exposure.

In contrast, true transgenerational inheritance is only demonstrable in the F3 generation and beyond following maternal line exposure, as these generations were not directly exposed to the original stimulus [1]. This temporal distinction has profound implications for experimental design, as studies concluding transgenerational inheritance based solely on F2 observations in maternal exposure models are methodologically flawed. The situation differs for paternal exposures, where transgenerational effects can be observed in the F2 generation, as the only directly exposed generation is the F0 father and his F1 germ cells [2].

Evolutionary and Biological Rationale

The persistence of non-genetic inheritance across generations raises fundamental questions about its evolutionary significance and biological rationale. From an adaptive perspective, intergenerational effects (typically lasting 1-2 generations) potentially evolved to transmit crucial environmental information to immediate offspring without permanently altering the genetic code [4]. This mechanism allows organisms to respond to transient environmental challenges while maintaining genetic stability across evolutionary timescales. Examples of such adaptive responses include the development of wings in pea aphids when parents experience stress and diapause regulation in silk moths [4].

Transgenerational effects, persisting for three or more generations, may represent either a maladaptive consequence of severe environmental disruption or a mechanism for long-term adaptation. The transmission of epigenetic information beyond the F3 generation suggests that certain environmental exposures can induce relatively stable epigenetic reprogramming of the germline, potentially leading to increased disease susceptibility across multiple generations [5]. The trade-offs between adaptive plasticity and maladaptive pathology form a central focus in transgenerational epigenetics research, particularly in the context of EDC exposures [4].

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Establishing a Transgenerational Inheritance Study

The demonstration of bona fide transgenerational inheritance requires meticulous experimental design with particular attention to generational tracking, proper controls, and route of exposure. The following workflow outlines the critical steps for establishing a transgenerational inheritance study:

Key Methodological Protocols

Animal Model Selection and Breeding Scheme

The selection of appropriate animal models and implementation of a rigorous breeding scheme are fundamental to transgenerational research. For mammalian studies, rodents (particularly rats and mice) are the most widely used models due to their relatively short generation times and well-characterized epigenomes. The breeding protocol must be designed to distinguish between maternal exposure and paternal exposure scenarios, as the generational boundaries for transgenerational inheritance differ between these routes [1] [2].

For maternal exposure studies, the recommended breeding scheme involves:

- F0 Generation: Expose pregnant dams during the period of gonadal sex determination in the embryos (typically E8-E14 in mice, E8-E18 in rats).

- F1 Generation: Breed exposed F1 females with unexposed control males to produce F2 offspring.

- F2 Generation: Breed F2 females with unexposed control males to produce F3 offspring.

- F3 Generation: This represents the first transgenerational generation for maternal exposure, as no direct exposure occurred [1].

For paternal exposure studies:

- F0 Generation: Expose males during spermatogenesis or prior to mating.

- F1 Generation: Breed exposed F0 males with unexposed females.

- F2 Generation: This represents the first transgenerational generation for paternal exposure, as only the F0 germline was directly exposed [2].

Throughout the breeding scheme, it is critical to maintain strict environmental controls, including temperature, light cycles, and diet, to minimize confounding variables. All breeding should be conducted using outcrossing to unexposed partners to distinguish germline transmission from other inheritance mechanisms.

Epigenetic Analysis of Germ Cells and Somatic Tissues

Comprehensive epigenetic profiling is essential for establishing mechanistic links between environmental exposures and heritable phenotypic changes. The following protocol outlines a multi-tiered approach to epigenetic analysis in transgenerational inheritance studies:

Germ Cell Isolation and Processing:

- Isolate primordial germ cells from E13.5 embryos or collect mature sperm from adult animals.

- Extract genomic DNA using gentle extraction methods to preserve epigenetic marks.

- Isect RNA for small RNA sequencing to profile miRNA, piRNA, and other non-coding RNAs.

DNA Methylation Analysis:

- Perform whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) to assess global methylation patterns.

- Conduct reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) for cost-effective methylation analysis of CpG-rich regions.

- Utilize pyrosequencing for validation of candidate differentially methylated regions (DMRs).

Histone Modification Profiling:

- Perform chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for key histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K9ac, etc.).

- Utilize low-cell number ChIP protocols (e.g., CUT&RUN, CUT&Tag) for germ cell analyses.

Data Integration and Validation:

- Integrate multi-omics datasets to identify persistently altered epigenetic regulatory regions across generations.

- Validate candidate regions using targeted epigenetic editing approaches (CRISPR-dCas9 systems).

- Correlate epigenetic changes with transcriptional changes in relevant tissues.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Transgenerational Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals | Bisphenol A (BPA), Vinclozolin, Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) [2] | Model compounds for inducing transgenerational effects through hormonal pathways. |

| Epigenetic Analysis Kits | Bisulfite conversion kits, ChIP-grade antibodies, DNA methyltransferase assays [1] | Detection and quantification of epigenetic modifications in germ cells and somatic tissues. |

| Germ Cell Isolation Reagents | Collagenase, Trypsin-EDTA, Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) antibodies | Isolation of pure germ cell populations for epigenetic analysis. |

| Molecular Biology Tools | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing kits, Small RNA sequencing library prep kits [5] | Comprehensive profiling of epigenetic marks across generations. |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Epigenetic Mechanisms of Transgenerational Inheritance

The molecular basis of transgenerational inheritance involves three primary epigenetic mechanisms that can escape the widespread epigenetic reprogramming that occurs during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis. These mechanisms work in concert to maintain epigenetic information across generational boundaries:

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation represents the most extensively studied mechanism in transgenerational epigenetics. This process involves the addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases within CpG dinucleotides, typically leading to transcriptional repression when occurring in promoter regions [1]. During normal development, two major waves of epigenetic reprogramming occur: first, shortly after fertilization, and second, during primordial germ cell development [5]. These reprogramming events involve widespread erasure and reestablishment of DNA methylation patterns, with most environmentally-induced methylation changes being reset.

However, certain genomic regions can evade this reprogramming, including imprinted genes, retrotransposons, and some repetitive elements [5]. EDCs such as vinclozolin and BPA have been shown to induce altered DNA methylation patterns in sperm that persist across multiple generations, particularly in differentially methylated regions (DMRs) [3]. These transgenerationally persistent DMRs are often located in gene promoters and regulatory elements associated with diseases that manifest in subsequent generations, providing a potential mechanistic link between environmental exposures and heritable disease risk.

Histone Modifications

Histone modifications constitute another crucial epigenetic mechanism in transgenerational inheritance. Histones undergo various post-translational modifications, including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, which collectively regulate chromatin structure and gene accessibility [5]. These modifications can form a "histone code" that influences transcriptional states and can be maintained through cell divisions.

In the context of transgenerational inheritance, certain histone modifications have been shown to resist reprogramming during gametogenesis. For example, H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 have been implicated in the transmission of epigenetic information across generations [5]. EDC exposure can alter the enzymatic machinery responsible for establishing and maintaining these histone marks, including histone methyltransferases and demethylases, leading to persistent changes in chromatin states that can be transmitted to subsequent generations [1].

Non-coding RNAs

Various classes of non-coding RNAs have emerged as important mediators of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. This includes microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) that can regulate gene expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [5]. These RNA species can be directly transmitted through gametes and influence embryonic development and gene expression in the resulting offspring.

In animal models, exposure to EDCs and other environmental stressors has been shown to alter the composition of small RNAs in sperm, which can mediate the transmission of acquired traits to subsequent generations [5]. The RNA-mediated pathway is particularly significant as it provides a mechanism for the rapid adaptation to environmental changes without altering DNA sequence or permanent epigenetic marks. Furthermore, non-coding RNAs can interact with other epigenetic mechanisms, such as directing DNA methylation to specific genomic loci, creating a complex regulatory network for transgenerational inheritance.

Applications in Hormone Modulation Research

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals as Model Compounds

Endocrine disrupting chemicals serve as powerful model compounds for studying transgenerational inheritance due to their ability to interfere with hormonal signaling during critical developmental windows. Three well-characterized classes of EDCs have been particularly informative in transgenerational research:

Bisphenols: Bisphenol A (BPA) and its analogs (BPS, BPF, BPAF) are industrial chemicals used in plastics manufacturing that exhibit estrogenic activity [2]. Transgenerational studies have demonstrated that developmental exposure to BPA can induce reproductive abnormalities, metabolic disorders, and behavioral changes persisting into the F3 generation and beyond. The estimated exposure in humans ranges from 0.01 to 13 µg/kg/day for children and up to 4.2 µg/kg/day for adults, with safety levels set at 50 µg/kg/day by the US-EPA [2].

Phthalates: Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), and other phthalates are widely used as plasticizers and have been associated with transgenerational inheritance of reproductive abnormalities and metabolic disorders [1] [2]. The mechanisms involve altered DNA methylation patterns in sperm and disruption of steroid hormone signaling pathways.

Vinclozolin: This fungicide used in agricultural applications has become a prototypical compound in transgenerational research due to its potent anti-androgenic effects and ability to induce transgenerational disease phenotypes [2]. Exposure during gestation has been shown to promote reproductive abnormalities, kidney disease, and tumor development across multiple generations through altered DNA methylation patterns in the germline.

Implications for Drug Development and Safety Assessment

The phenomenon of transgenerational inheritance has profound implications for pharmaceutical development and safety assessment protocols. Traditional toxicological studies typically examine direct exposure effects within a single generation, potentially missing heritable epigenetic effects that manifest in subsequent generations. Incorporating transgenerational assessment into safety evaluation protocols requires:

- Extended Generational Testing: Including F2 and F3 generations in safety assessment protocols for compounds with hormonal activity or epigenetic modifying potential.

- Germline Epigenetic Profiling: Implementing standardized epigenetic screening of sperm and oocytes from exposed animals to identify potential heritable epigenetic alterations.

- Multi-generational Phenotypic Screening: Comprehensive health assessment across multiple generations, including metabolic, reproductive, neurological, and immunological endpoints.

Furthermore, understanding transgenerational epigenetic mechanisms opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention, targeting the epigenetic machinery to prevent or reverse the inheritance of acquired disease susceptibilities. The emerging field of epi-drug development focuses on compounds that can modify epigenetic marks, potentially offering strategies to mitigate transgenerational disease risks.

The distinction between transgenerational and multigenerational inheritance represents a critical conceptual framework with significant methodological implications for research on hormonal modulation and epigenetic inheritance. Proper experimental design must account for the fundamental differences in generational exposure status, with particular attention to the minimum generational requirements for establishing true transgenerational inheritance. The molecular mechanisms involving DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs provide a mechanistic basis for the transmission of environmental information across generations without altering DNA sequence.

As research in this field advances, standardized protocols and rigorous methodological approaches will be essential for distinguishing between direct exposure effects and bona fide germline epigenetic inheritance. This distinction has profound implications for understanding disease etiology, assessing chemical safety, and developing novel therapeutic strategies that address the heritable consequences of environmental exposures.

Epigenetics represents the study of heritable changes in gene function that occur without altering the underlying DNA sequence [6]. These dynamic modifications form a crucial regulatory layer that translates genetic information into cellular phenotypes, serving as a key mechanism through which environmental factors, including hormone exposure, can induce lasting biological changes. The transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic states provides a plausible molecular framework for understanding how ancestral exposures can influence offspring phenotypes [7]. For researchers investigating the transgenerational effects of hormone modulation, a comprehensive understanding of three core epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs—is essential for designing methodologically sound studies and accurately interpreting resulting data.

This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for investigating these key epigenetic mechanisms within the specific context of transgenerational hormone research. The guidance is structured to equip scientists with practical methodologies for capturing epigenetic changes across generations, with particular emphasis on protocols suitable for analyzing limited biological samples often encountered in multi-generational studies.

DNA Methylation: Protocols and Applications

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine bases, primarily within CpG dinucleotides [8] [6]. This modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT1 maintaining existing methylation patterns during DNA replication, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish de novo methylation patterns [9]. In mammalian systems, DNA methylation typically leads to gene silencing by altering chromatin structure and preventing transcription factor binding [6]. The reversible nature of this modification, facilitated by Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) family enzymes that initiate demethylation, makes it a dynamic regulator of gene expression in response to environmental cues [6].

Application in Transgenerational Studies

DNA methylation analysis is particularly valuable in transgenerational hormone research because methylation patterns can be maintained through cell divisions and potentially transmitted across generations, serving as molecular footprints of ancestral exposures [7]. Studies in plant systems have demonstrated that specific genetic sequences can instruct new DNA methylation patterns, revealing a paradigm-shifting mechanism for establishing novel epigenetic states that could be transmitted to offspring [10]. In the context of hormone modulation, researchers can investigate whether parental hormone exposures establish persistent DNA methylation patterns at genes regulating endocrine function, metabolism, or stress response in subsequent generations.

Table 1: DNA Methylation Analysis Methods for Transgenerational Studies

| Method | Resolution | Throughput | Key Applications in Hormone Research | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | Genome-wide | Discovery of novel differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in hormone-responsive genes | High-quality DNA (>100ng) |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base | Targeted (CpG-rich regions) | Cost-effective profiling of promoter regions in large multi-generational cohorts | DNA (50-100ng) |

| Bisulfite Pyrosequencing | Quantitative single-base | Locus-specific | Validation of candidate DMRs in hormone pathway genes | DNA (10-20ng) |

| Methylation-Sensitive High-Resolution Melting (MS-HRM) | Regional | Locus-specific | Rapid screening of hormone receptor promoter methylation | DNA (5-10ng) |

| EPIC Array | Single-CpG | Genome-wide (850,000 CpGs) | Standardized analysis of predefined regulatory elements in population studies | DNA (250-500ng) |

Detailed Protocol: RRBS for Multi-Generational Sampling

Principle: RRBS combines restriction enzyme digestion with bisulfite sequencing to enrich for CpG-dense genomic regions, providing a cost-effective approach for DNA methylation analysis in multi-generational studies [8].

Workflow:

DNA Quality Control and Quantification

- Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for accurate DNA quantification

- Verify DNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis or Fragment Analyzer

- Minimum requirement: 50ng high-quality genomic DNA (A260/A280 = 1.8-2.0)

MspI Restriction Digestion

- Set up digestion reaction:

- Genomic DNA: 50-100ng

- MspI (20U/μL): 20 units

- CutSmart Buffer: 5μL

- Nuclease-free water to 50μL

- Incubate at 37°C for 8 hours followed by enzyme inactivation at 65°C for 20 minutes

- Set up digestion reaction:

End-Repair and Adenylation

- Prepare end-repair master mix:

- Klenow Fragment (3'→5' exo-): 5 units

- dNTPs (10mM each): 0.4μL

- T4 DNA Polymerase: 1 unit

- T4 Polynucleotide Kinase: 5 units

- Corresponding buffers as manufacturer recommended

- Incubate at 30°C for 30 minutes, then clean up using AMPure XP beads

- Prepare end-repair master mix:

Adapter Ligation

- Use methylated adapters compatible with bisulfite sequencing

- Ligation reaction:

- Digested DNA: 45μL

- Methylated Adapters (15μM): 2μL

- T4 DNA Ligase (400U/μL): 1.5μL

- Ligase Buffer: 5.5μL

- Incubate at 16°C for 16 hours

Bisulfite Conversion

- Use commercial bisulfite conversion kit (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit)

- Convert 200ng adapter-ligated DNA following manufacturer's protocol

- Desulfonate and elute in 20μL elution buffer

Library Amplification and Size Selection

- Perform PCR amplification with bisulfite-converted DNA

- PCR conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 12-15 cycles: 95°C for 30s, 60°C for 30s, 72°C for 45s

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

- Size-select 150-400bp fragments using AMPure XP beads

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Sequence on Illumina platform (PE 150bp recommended)

- Align reads using Bismark or BS-Seeker2

- Perform differential methylation analysis with methylKit or DSS

Critical Considerations for Transgenerational Studies:

- Process all generational samples in the same batch to minimize technical variation

- Include both exposed and control lineages across multiple generations

- Spike-in unmethylated lambda DNA to monitor conversion efficiency

- Account for potential genetic sequence variation when interpreting methylation differences

Diagram 1: RRBS workflow for DNA methylation analysis in transgenerational studies.

Histone Modifications: Protocols and Applications

Histone modifications represent post-translational chemical modifications to histone proteins that package DNA into chromatin [9]. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination occurring primarily on the N-terminal tails of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 [9] [11]. The combinatorial nature of these modifications forms a "histone code" that regulates chromatin accessibility and gene expression [6]. For example, histone acetylation generally promotes an open chromatin state and gene activation, while specific methylation patterns can either activate or repress transcription depending on the modified residue and methylation state [11]. These modifications are dynamically regulated by opposing enzyme families: histone acetyltransferases (HATs) versus histone deacetylases (HDACs), and histone methyltransferases (HMTs) versus histone demethylases (KDMs) [6].

Application in Transgenerational Studies

Histone modifications are increasingly recognized as potential carriers of transgenerational epigenetic information, though their mechanisms of transmission are less well characterized than DNA methylation [11]. In the context of hormone modulation research, histone modifications offer insights into the chromatin states that potentially maintain gene expression programs across generations. For example, parental hormone exposures might establish persistent H3K4me3 (activating) or H3K27me3 (repressive) marks at genes involved in hormone synthesis, metabolism, or signaling that are transmitted to offspring. Studies in model organisms suggest that certain histone modifications can survive the extensive epigenetic reprogramming that occurs during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis, positioning them as potential transgenerational epigenetic carriers.

Table 2: Histone Modification Analysis Methods for Transgenerational Studies

| Method | Target | Resolution | Information Output | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-Seq | Genome-wide histone marks | 200-500bp | Binding sites and enrichment peaks | 1-10 million cells per immunoprecipitation |

| CUT&Tag | Genome-wide histone marks | Single-nucleosome | Mapping with lower cell input | 50,000-500,000 cells |

| ChIP-qPCR | Candidate loci | Locus-specific | Quantitative enrichment at specific regions | 0.5-1 million cells |

| Histone Modification Immunoblotting | Global levels | Protein-level | Abundance of specific modifications | 50-100μg total protein |

| Immunofluorescence | Nuclear localization | Single-cell | Spatial distribution and cell-to-cell variation | Fixed cells on coverslips |

Detailed Protocol: Low-Input CUT&Tag for Histone Modification Profiling

Principle: Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) uses a protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion protein targeted to specific histone modifications by antibodies, enabling efficient tagmentation and library construction with low cell inputs—particularly valuable for transgenerational studies where sample material may be limited.

Workflow:

Cell Preparation and Permeabilization

- Isolate nuclei from tissue (e.g., hypothalamic regions, gonads) of F1-F3 generation offspring

- Wash cells with Wash Buffer (20mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 0.5mM Spermidine, 1× protease inhibitors)

- Resuspend 50,000-100,000 cells in 50μL Wash Buffer

- Add activated Concanavalin A-coated magnetic beads (10μL per sample) and incubate 15 minutes at room temperature

Antibody Binding

- Prepare primary antibody solution in Antibody Buffer (Wash Buffer + 0.01% Digitonin + 2mM EDTA):

- Anti-histone antibody (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3): 1-2μg

- Species-matched non-specific IgG as control

- Incubate with beads-bound cells overnight at 4°C

- Prepare primary antibody solution in Antibody Buffer (Wash Buffer + 0.01% Digitonin + 2mM EDTA):

pA-Tn5 Adapter Complex Binding

- Prepare pA-Tn5 adapter complex by incubating protein A-Tn5 transposase (2.5μM) with assembled mosaic end adapters (10μM) for 30 minutes at room temperature

- Wash cells twice with 200μL Dig-Wash Buffer (Wash Buffer + 0.01% Digitonin)

- Resuspend in 50μL Dig-Wash Buffer containing 1:100 dilution of pA-Tn5 adapter complex

- Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature

Tagmentation

- Wash cells twice with 200μL Dig-Mg Buffer (Dig-Wash Buffer + 10mM MgCl₂)

- Resuspend in 50μL Dig-Mg Buffer

- Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour

- Stop tagmentation by adding 2.5μL 0.5M EDTA, 1.25μL 10% SDS, and 1.25μL 20mg/mL Proteinase K

- Incubate at 55°C for 30 minutes to digest proteins

DNA Purification and Library Amplification

- Extract DNA with phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1)

- Precipitate with ethanol and glycogen carrier

- Resuspend in 21μL TE buffer

- Prepare PCR reaction:

- DNA: 20μL

- Universal i5 and i7 primers (15μM each): 2.5μL each

- 2× NEB Next High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix: 25μL

- Amplify with cycling conditions:

- 72°C for 5 minutes

- 98°C for 30 seconds

- 13-16 cycles: 98°C for 10s, 63°C for 10s, 72°C for 30s

Library Purification and Sequencing

- Clean up with AMPure XP beads (1.2× ratio)

- Quality control via Bioanalyzer/TapeStation

- Sequence on Illumina platform (SE 50bp sufficient for most applications)

Critical Considerations for Transgenerational Studies:

- Use the same antibody lot for all generational samples to ensure consistency

- Include biological replicates from multiple litters within each generation

- Process control and experimental lineages simultaneously

- Validate key findings with orthogonal methods (e.g., ChIP-qPCR)

Diagram 2: Hormonal regulation of gene expression through histone modifications.

Non-Coding RNAs: Protocols and Applications

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) represent a diverse class of functional RNA molecules that do not encode proteins but play crucial regulatory roles in gene expression [12] [13]. These include microRNAs (miRNAs, ~22 nucleotides), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs, >200 nucleotides), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and others [9] [12]. These regulatory RNAs operate through diverse mechanisms: miRNAs typically bind to target mRNAs to induce degradation or translational repression [13]; lncRNAs can interact with chromatin-modifying complexes to influence epigenetic states [12]; while circRNAs can function as miRNA sponges or protein scaffolds [12]. A specialized subclass termed "epi-miRNAs" can directly target epigenetic regulators like DNMTs, HDACs, and TETs, creating integrated feedback loops between the different epigenetic layers [13].

Application in Transgenerational Studies

ncRNAs are emerging as promising candidates for mediating transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of hormone-induced phenotypes [12]. Gametes (sperm and oocytes) carry diverse ncRNA populations that can potentially transmit information to the next generation. In hormone modulation research, investigators can examine whether parental hormone exposures alter ncRNA profiles in gametes and whether these altered ncRNA signatures are associated with phenotypic outcomes in offspring. For example, changes in sperm miRNA content following parental hormone disruption might program metabolic or reproductive traits in subsequent generations. The stability of certain ncRNAs, particularly circRNAs, makes them particularly interesting as potential durable signals that could survive the epigenetic reprogramming between generations.

Table 3: Non-Coding RNA Analysis Methods for Transgenerational Studies

| Method | Target RNA Class | Throughput | Key Applications | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small RNA-Seq | miRNAs, piRNAs, tRNA fragments | Genome-wide | Profiling of small RNA populations in gametes and embryos | Total RNA (100ng-1μg) |

| Total RNA-Seq | lncRNAs, circRNAs, mRNAs | Genome-wide | Transcriptome-wide analysis of coding and non-coding RNAs | Total RNA (100ng-1μg) |

| RT-qPCR | Specific miRNAs/lncRNAs | Targeted | Validation of candidate ncRNAs | Total RNA (10-100ng) |

| Nanostring nCounter | Predefined ncRNA panels | Multiplexed | Targeted analysis without amplification bias | Total RNA (100-300ng) |

| CircRNA-Specific RNA-Seq | Circular RNAs | Genome-wide | Enrichment and identification of circRNAs | Total RNA (1-2μg) |

Detailed Protocol: Small RNA Sequencing from Limited Samples

Principle: Small RNA sequencing specifically enriches for and sequences RNAs in the 18-40 nucleotide size range, enabling comprehensive profiling of miRNAs and other small regulatory RNAs that may serve as transgenerational signals following hormone exposure.

Workflow:

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract total RNA using miRNeasy Mini Kit or equivalent

- Include phase separation to recover small RNAs

- Assess RNA quality using Bioanalyzer RNA Nano or Small RNA Kit

- Minimum requirement: 100ng total RNA with RIN >7.0

3' Adapter Ligation

- Prepare 3' adapter ligation reaction:

- Total RNA: 100ng

- 3' SR Adaptor (25μM): 1μL

- T4 RNA Ligase 2, truncated (200U/μL): 1μL

- PEG 8000 (50%): 6μL

- RNase Inhibitor (40U/μL): 0.5μL

- T4 RNA Ligase Buffer: 1μL

- Incubate at 25°C for 1 hour

- Prepare 3' adapter ligation reaction:

5' Adapter Ligation

- Purify ligation products using RNA Clean XP beads (1.8× ratio)

- Prepare 5' adapter ligation reaction:

- 3' ligated RNA: 12.5μL

- 5' SR Adaptor (25μM): 1μL

- T4 RNA Ligase (30U/μL): 1μL

- PEG 8000 (50%): 6μL

- ATP (10mM): 1μL

- DMSO: 1μL

- RNase Inhibitor (40U/μL): 0.5μL

- T4 RNA Ligase Buffer: 1μL

- Incubate at 25°C for 1 hour

Reverse Transcription and PCR Amplification

- Purify ligation products with RNA Clean XP beads (1.8× ratio)

- Perform reverse transcription with RT primer

- Set up PCR reaction:

- cDNA: 10μL

- Universal Reverse Primer (25μM): 1μL

- Indexed Forward Primer (25μM): 1μL

- 2× KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix: 13μL

- Amplify with cycling conditions:

- 98°C for 45 seconds

- 10-12 cycles: 98°C for 15s, 60°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s

- Final extension: 72°C for 1 minute

Size Selection and Library Quality Control

- Run PCR products on 6% TBE PAGE gel

- Excise bands corresponding to 145-160bp (miRNA insert + adapters)

- Crush gel slice and elute in 300μL 0.3M NaCl overnight at 4°C

- Precipitate with ethanol and resuspend in 15μL TE buffer

- Validate library quality using Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA kit

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Sequence on Illumina platform (SE 50bp recommended)

- Process raw data: adapter trimming, quality filtering

- Align to reference genome using Bowtie or STAR

- Quantify miRNAs with miRDeep2 or similar tools

- Identify differentially expressed miRNAs with DESeq2 or edgeR

Critical Considerations for Transgenerational Studies:

- Process all generational samples simultaneously to minimize batch effects

- Include external RNA controls (e.g., ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix) for normalization

- For sperm RNA analyses, include DNase treatment to remove contaminating DNA

- Validate key miRNA changes with RT-qPCR using specific stem-loop primers

Diagram 3: Non-coding RNA mechanisms in epigenetic regulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Epigenetic Studies in Transgenerational Hormone Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Inhibitors | 5-Azacytidine, Decitabine | DNMT inhibition; DNA hypomethylation | Confirm demethylation with locus-specific analyses; use at low concentrations (0.1-5μM) to avoid toxicity |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Vorinostat, Trichostatin A | Pan-HDAC inhibition; histone hyperacetylation | Assess acetylation changes via immunoblotting; monitor cell viability as high concentrations induce apoptosis |

| HAT Inhibitors | Garcinol, C646 | HAT inhibition; reduced histone acetylation | Validate specificity with multiple HAT family members; use chromatin-bound fraction for activity assays |

| Bromodomain Inhibitors | JQ1, I-BET762 | Reader domain inhibition; disrupts recognition of acetylated histones | Effective in cancer and inflammation models; assess BET protein displacement with cellular localization assays |

| EZH2 Inhibitors | GSK126, Tazemetostat | H3K27me3 inhibition; reactivation of silenced genes | Verify target engagement via H3K27me3 reduction; combination approaches often needed for full effect |

| DNMT Antibodies | Anti-5-methylcytosine, Anti-DNMT1 | Detection of global methylation, enzyme localization | Optimize for specific applications (IHC, WB, IF); validate with positive and negative controls |

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27me3, Anti-H3K9ac | Chromatin immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting | Verify specificity with peptide competition; use ChIP-grade validated antibodies for sequencing applications |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation series | Convert unmethylated cytosine to uracil | Include unmethylated and methylated DNA controls; optimize conversion time to balance completeness and DNA damage |

| Small RNA Library Prep Kits | NEBNext Small RNA Library | Construction of sequencing libraries from small RNAs | Include size selection steps to enrich for specific RNA classes; use unique molecular identifiers to reduce amplification bias |

Integrated Experimental Design for Transgenerational Epigenetic Studies

Successful investigation of transgenerational epigenetic effects requires careful experimental design that accounts for the unique challenges of multi-generational research. Below is a recommended framework for designing studies examining the transgenerational effects of hormone modulation:

Generational Cohort Establishment:

- F0 Generation: Expose during critical developmental windows (e.g., gestation, puberty)

- F1 Generation: Direct fetal exposure (if F0 exposed during pregnancy)

- F2 Generation: First potentially transgenerational cohort (germline exposure only)

- F3 Generation: Definitive transgenerational cohort (no direct exposure)

Tissue Collection Strategy:

- Collect multiple tissues relevant to hormone signaling (hypothalamus, pituitary, gonads, liver)

- Preserve tissues for multiple genomic analyses (flash freeze for RNA/DNA, fix for histology)

- Bank gametes (sperm, oocytes) for germline-focused epigenetic analyses

- Consider temporal sampling across development in offspring generations

Control Groups:

- Vehicle-treated controls maintained under identical conditions

- Outbred strains to capture genetic diversity relevant to human populations

- Consider including positive control compounds with known transgenerational effects

Integrated Multi-Omic Analysis:

- Process samples for DNA methylation (RRBS/WGBS), histone modifications (CUT&Tag), and ncRNA profiling (small RNA-seq) in parallel

- Apply consistent bioinformatic pipelines across all generational cohorts

- Integrate datasets to identify coordinated epigenetic changes across modalities

This integrated approach enables researchers to capture the complexity of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance and determine whether hormone exposures establish stable epigenetic memories that persist across multiple generations through combined alterations in DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA regulation.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous substances that interfere with the normal function of the body's hormonal systems [14]. The study of EDCs such as vinclozolin, bisphenol A (BPA), and phthalates using animal models has provided critical insights into their mechanisms of action, transgenerational effects, and broader health implications. This document synthesizes key methodological approaches and findings from animal studies investigating these compounds, with particular focus on experimental design, molecular pathways, and epigenetic mechanisms relevant to researchers studying transgenerational effects of hormone modulation.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of EDC Effects in Animal Models

| EDC | Typical Doses in Animal Studies | Primary Exposure Routes | Key Organ Effects | Molecular Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinclozolin | 100-200 mg/kg/day [15] [14] | Oral administration [15] | Lung: inflammation, fibrosis, collagen deposition [15]; Vascular: endothelial dysfunction [16]; Reproductive: anti-androgenic effects [15] | Oxidative stress, Nf-kb pathway activation, Nrf-2/HO-1 suppression, apoptosis [15] |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | 0.5-50 μg/kg/day [14] [17] | Food, water, dermal [17] | Ovarian: reduced follicular growth, PCOS-like symptoms [17]; Testicular: altered spermatogenesis [17]; Brain: altered development [18] | Estrogen receptor binding, steroidogenesis disruption, epigenetic modifications [17] |

| Phthalates (e.g., DEHP, DBP) | 20-750 mg/kg/day [19] [14] | Food, inhalation, dermal [19] | Reproductive: testicular atrophy, reduced sperm count [19]; Developmental: malformations, reduced weight [19]; Placental: altered gene methylation [20] | Androgen receptor antagonism, PPAR activation, oxidative stress, DNA methylation changes [19] [20] |

Table 2: Transgenerational Inheritance Patterns of EDC Effects

| Exposure Scenario | Directly Exposed Generations | First Unexposed Generation | Key Epigenetic Mechanisms | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant F0 female exposed | F0 (mother), F1 (in utero), F2 (germ cells) [14] | F3 [14] | DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNAs [14] | Vinclozolin: F3 ovarian disease, sperm defects [14]; Phthalate mixture: F3 ovarian follicle reduction [14] |

| F0 male or non-pregnant female exposed | F0 (exposed individual), F1 (germ cells) [14] | F2 [14] | Germline epigenetic alterations [14] | Vinclozolin: F2-F3 testicular and prostate abnormalities [14]; BPA: F2 behavioral changes [21] |

Experimental Protocols for EDC Research

Protocol: 28-Day Oral Vinclozolin Exposure and Lung Toxicity Assessment

Background: This protocol assesses the effects of chronic vinclozolin exposure on non-reproductive organs, specifically lung tissue, in murine models [15].

Materials:

- Experimental animals (e.g., C57BL/6 mice)

- Vinclozolin ((RS)-3-(3,5-Dichlorophenyl)-5-methyl-5-vinyloxazolidine-2,4-dione)

- Corn oil vehicle

- Tissue collection supplies (dissection tools, cryovials, etc.)

- Western blot equipment and reagents

- ELISA kits for ROS, H2O2, RNS, and interleukins

- Histology supplies (fixatives, stains including Masson's trichrome)

- TUNEL assay kit for apoptosis detection

Procedure:

- Preparation of Test Substance: Prepare vinclozolin at 100 mg/kg in corn oil vehicle. Maintain fresh aliquots for daily administration [15].

- Animal Dosing: Administer vinclozolin solution orally to experimental group daily for 28 days. Control groups receive corn oil vehicle only [15].

- Tissue Collection: Euthanize animals 24 hours after final dose. Collect lung tissues and separate into aliquots for (a) histology (fixed in formalin), (b) protein analysis (flash frozen), and (c) molecular analysis (flash frozen) [15].

- Histological Analysis: Process fixed tissues, embed in paraffin, section at 5μm, and stain with H&E for general morphology and Masson's trichrome for collagen deposition. Score inflammatory infiltrates and fibrotic lesions [15].

- Molecular Analysis:

- Perform Western blotting for Nf-kb pathway proteins (Ikb-α degradation, Nf-kb nuclear translocation) and Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway [15].

- Conduct ELISA assays for ROS, H2O2, RNS, and cytokines (IL-1β, IL-18, IL-6, IL-10, IL-4) according to manufacturer protocols [15].

- Assess antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GPx, CAT) activity using commercial assay kits [15].

- Apoptosis Assessment: Perform TUNEL assay on lung sections and Western blotting for Bax/Bcl-2 ratio to quantify apoptotic changes [15].

- Data Analysis: Compare experimental and control groups using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA with post-hoc analysis).

Protocol: Transgenerational EDC Exposure Model

Background: This protocol outlines methods for studying multigenerational and transgenerational inheritance of EDC effects through germline epigenetic modifications [14].

Materials:

- Gestating F0 females (rats or mice)

- EDCs of interest (vinclozolin, BPA, phthalates, or mixtures)

- Breeding supplies (cages, pedigree tracking system)

- Tissue collection supplies for multiple generations

- Epigenetic analysis equipment (bisulfite conversion reagents, methylation arrays, sequencing platforms)

Procedure:

- F0 Generation Exposure: Expose gestating F0 females to EDCs during critical periods of germline development (e.g., E8-E14 in rats) [14].

- Generational Breeding:

- Breed exposed F1 offspring to unexposed control animals to produce F2 generation.

- Breed F2 animals to produce F3 generation (first potentially transgenerational generation) [14].

- Continue to F4 and beyond to confirm true transgenerational inheritance.

- Tissue Collection and Phenotyping: At each generation, collect relevant tissues for:

- Reproductive organs (testes, ovaries) for histological analysis

- Sperm and oocytes for epigenetic analysis

- Blood for hormone level assessment

- Other organs based on suspected effects (e.g., lung, kidney, brain) [14]

- Epigenetic Analysis:

- Extract DNA from germ cells and target tissues

- Perform genome-wide DNA methylation analysis (e.g., Illumina MethylationEPIC array)

- Validate candidate differentially methylated regions with bisulfite sequencing

- Analyze histone modifications via ChIP-seq where appropriate

- Assess non-coding RNA expression profiles [14]

- Data Integration: Correlate epigenetic modifications with phenotypic outcomes across generations using bioinformatic approaches.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Vinclozolin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis Pathway

Figure 1: Vinclozolin-induced cellular stress pathway. Vinclozolin exposure triggers reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, leading to oxidative stress that simultaneously activates pro-inflammatory Nf-kb signaling while suppressing protective Nrf-2 pathways, ultimately resulting in cellular apoptosis [15].

Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance Mechanism

Figure 2: Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. When F0 generation is exposed to EDCs during critical windows of germ cell development, epigenetic modifications become programmed in the germline and can be transmitted through multiple generations, resulting in phenotypic changes even in unexposed F3 individuals [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for EDC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in EDC Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDC Compounds | Vinclozolin, Bisphenol A, DEHP, DBP [15] [19] [17] | In vivo exposure studies | Direct test substances for evaluating endocrine disruption effects |

| Vehicle Substances | Corn oil, Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [15] [16] | Solubilization and administration of EDCs | Enable proper delivery of lipophilic EDCs in animal models |

| Molecular Biology Kits | ELISA kits (ROS, H2O2, RNS, cytokines) [15], Western blot reagents [15] | Oxidative stress and inflammation assessment | Quantify molecular responses to EDC exposure |

| Epigenetic Analysis Tools | Illumina Methylation BeadChips [20], Bisulfite conversion kits [20] | DNA methylation profiling | Identify epigenetic modifications associated with EDC exposure |

| Histology Supplies | Masson's trichrome stain [15], H&E stain [15], TUNEL assay kits [15] | Tissue morphology and apoptosis detection | Visualize structural and cellular changes in target organs |

| Antibodies | Anti-Bax, Anti-Bcl-2, Anti-Nf-kb, Anti-Ikb-α [15] | Protein expression analysis by Western blot/IHC | Detect expression changes in apoptosis and inflammation pathways |

Animal model studies of EDCs such as vinclozolin, BPA, and phthalates have established robust methodological approaches for investigating the transgenerational effects of hormone modulation. The protocols and data summarized here provide a framework for designing studies that can elucidate the complex mechanisms through which environmental exposures program biological changes across generations. Future research in this field should prioritize standardized exposure protocols, integrated multi-omics approaches, and careful consideration of dose-response relationships relevant to human exposure levels.

Understanding the windows of susceptibility during germ cell reprogramming is fundamental for hormone modulation research. Primordial Germ Cells (PGCs), the progenitors of sperm and eggs, undergo two major waves of genome-wide epigenetic reprogramming in mammals, making them critically susceptible to environmental exposures, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and nutritional factors [22] [23]. During these periods, the elaborate orchestration of DNA methylation erasure, re-establishment, and histone modification is vulnerable to disruption. Such disruptions can alter the germline's epigenetic blueprint, leading to molecular changes that are stably transmitted across generations, a phenomenon known as transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [2] [24] [25]. This application note details the key methodologies for identifying these susceptible windows and for investigating the consequent transgenerational effects of hormone-modulating compounds.

Key Experimental Models and Readouts for Germline Studies

Selecting an appropriate model system is a primary methodological consideration. The following table summarizes the principal models used in germ cell reprogramming studies, their applications, and the key phenotypic readouts measured to assess transgenerational effects.

Table 1: Experimental Models for Studying Windows of Susceptibility in Transgenerational Research

| Experimental Model | Key Applications and Features | Primary Transgenerational Readouts |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse Model [23] | Gold standard for mammalian PGC studies; enables precise genetic and epigenetic manipulation; well-characterized PGC specification and migration. | Altered DNA methylation in F2/F3 PGCs; changes in histone modifications (H3K27me3, H3K9me2); offspring metabolic profiles, brain development, and behavior [2] [24]. |

| Chicken Embryo/PGC Model [22] | Allows precise temporal control over exposures without maternal confounding effects; liver is primary site of lipogenesis (90%), useful for metabolic studies; unique PGC epigenome without global DNA demethylation. | Sperm DNA methylation (5mC, 6mA) and non-coding RNA (miRNA, lncRNA) alterations; offspring growth, hepatic lipogenesis, and lipid/glucose metabolism profiles [22]. |

| Human Fetal Germ Cells (FGCs) [26] | Direct translation to human health; studied via in vitro culture systems; provides single-cell resolution epigenomic data. | Phase-specific chromatin accessibility; DNA methylation dynamics at imprinting control regions (ICRs) and retrotransposons (e.g., SVA, LINE-1); response of FGCs to BMP signaling pathway manipulation. |

| Zebrafish [27] | High fecundity, external development, transparency; excellent for high-throughput screening of EDCs; used to study parental (F0) social stress effects. | Offspring growth performance, feeding behavior, intestinal health, and gene expression patterns related to stress and inflammation [27]. |

Core Protocol: Profiling Epigenetic Susceptibility in Mammalian Germ Cells

This protocol outlines the procedure for assessing the impact of an exposure during the critical window of germ cell reprogramming in a mouse model, with a focus on downstream DNA methylation analysis.

Materials and Reagents

- Pregnant Mice: F0 generation, at specified gestational days (e.g., E8.5 for early PGC specification, E13.5 for gonadal PGCs).

- Test Compound: Hormone modulator or EDC (e.g., Bisphenol A, Vinclozolin) dissolved in appropriate vehicle.

- PGC Isolation Reagents: Collagenase/Dispase solution, FACS antibodies (e.g., anti-MVH, anti-SSEA1).

- DNA/RNA Extraction Kits: High-quality kits for low cell numbers (e.g., from Qiagen or Zymo Research).

- Bisulfite Conversion Kit: (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit, Zymo Research).

- Library Prep Kits: For Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) or Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS).

- scBS-seq/scCOOL-seq Reagents: As described in [26].

Step-by-Step Procedure

In Uero Exposure (F0 Generation):

- Time the mating of F0 mice to achieve precise gestational dates.

- Administer the test compound or vehicle control to pregnant dams via oral gavage or subcutaneous injection during the target window (e.g., E10.5-E12.5, covering peak PGC demethylation).

- Maintain a control group exposed to vehicle only.

Isolation of Fetal Gonads and PGC Sorting (F1 Generation):

- At E13.5, euthanize the pregnant dam and dissect the embryos. Collect the fetal gonads under a stereomicroscope.

- Digest the gonadal tissue using a collagenase-based enzyme mix to create a single-cell suspension.

- Stain the cells with fluorescently-labeled antibodies against PGC-specific surface markers (e.g., MVH, SSEA1).

- Isulate a pure population of PGCs using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). A portion of gonadal somatic cells should also be sorted as a control.

DNA Extraction and Bisulfite Conversion:

- Extract genomic DNA from the sorted F1 PGCs using a kit designed for low input.

- Treat the DNA with a bisulfite conversion kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. This process converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain as cytosines.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare sequencing libraries from the bisulfite-converted DNA. For genome-wide coverage, use WGBS. For a more cost-effective analysis targeting CpG-rich regions, use RRBS.

- Perform high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina platform to a recommended depth of >20x coverage for WGBS.

Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis:

- Align the sequenced reads to a bisulfite-converted reference genome using tools like

BismarkorBS-Seeker2. - Calculate methylation levels for each cytosine in the genome. Identify Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) between exposed and control PGCs using tools like

DSSormethylKit. - Annotate DMRs to genomic features (promoters, enhancers, gene bodies, transposable elements) and perform pathway enrichment analysis.

- Align the sequenced reads to a bisulfite-converted reference genome using tools like

Transgenerational Phenotyping (F2 and F3 Generations):

- Breed the exposed F1 generation to unexposed, wild-type partners to generate F2 offspring.

- The F2 germline carries the potential epigenetic alterations. Breed F2 individuals to generate F3 offspring, which is the first generation considered truly transgenerationally exposed if the F0 mother was exposed [2].

- In F2 and F3 adults, assess phenotypic endpoints relevant to the exposure, such as metabolic parameters (body weight, glucose tolerance), behavioral tests (anxiety, cognition), and reproductive function. Analyze PGCs/gametes from F2 for persistent epigenetic marks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Germ Cell and Transgenerational Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function and Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| LDN-193189 2HCl [26] | A selective BMP signaling pathway inhibitor; used to dissect the role of BMP signaling in germ cell development in vitro. | Culturing human FGCs to investigate how BMP signaling regulates proliferation and the WNT pathway via chromatin accessibility. |

| 5-Azacytidine (5-azaC) [28] | A DNA methyltransferase inhibitor; induces global DNA demethylation. Used to study the functional consequences of hypomethylation. | Treatment of plants or cell cultures to investigate the relationship between DNA methylation, hormone biosynthesis (ABA, auxin), and stress responses. |

| FACS Antibodies (e.g., anti-C-KIT, anti-MVH, anti-IL13RA2, anti-PECAM1) [26] | Enable isolation of pure populations of specific PGC phases (mitotic, meiotic, oogenetic) via fluorescence-activated cell sorting. | Isolation of phase-specific human FGCs (e.g., IL13RA2+ meiotic prophase FGCs) for single-cell epigenomic profiling. |

| DNMT & TET Enzyme Assays [23] [25] | Quantify the activity of DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, DNMT3A/B) and Ten-eleven translocation (TET) demethylases. | Profiling the enzymatic drivers of epigenetic reprogramming in germ cells following EDC exposure. |

| In Ovo Injection Setup [22] | A method for the precise delivery of nutrients, chemicals, or nucleic acids into chicken embryos, bypassing maternal effects. | Studying the effects of methyl donors (e.g., folic acid) or metabolic disruptors on the epigenetic state of chicken PGCs and subsequent offspring phenotype. |

Visualizing Signaling and Epigenetic Crosstalk in Germ Cells

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and epigenetic mechanisms that are active during germ cell reprogramming and are susceptible to disruption.

Figure 1: Signaling and Epigenetic Crosstalk in Germ Cells. This diagram outlines the core mechanism where external modulators like EDCs and nutrition disrupt key signaling pathways (BMP, WNT, Retinoic Acid) during critical windows of germ cell development. This disruption leads to alterations in the epigenetic machinery (DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNA), which can result in a permanently altered germline epigenome. When these modified germ cells form the next generation, they can give rise to transgenerational phenotypes in the F2 and F3 generations, even in the absence of direct exposure [22] [26] [25].

The investigation of transgenerational effects—where exposures in one generation (F0) lead to phenotypic changes in subsequent, unexposed generations (F2 and beyond)—represents a frontier in environmental and reproductive health research. Within this field, a central controversy persists, particularly in human studies: the challenge of reconciling associative epidemiological findings with definitive mechanistic proof. This application note examines this methodological divide, framing the issue within the context of hormone modulation research. For researchers and drug development professionals, this document provides a structured analysis of the current evidence, summarizes quantitative data, and offers detailed protocols to bridge the gap between population-level observations and molecular-level understanding, with a focus on epigenetic mechanisms as a primary mediator of these effects.

The Evidentiary Divide: Epidemiology vs. Mechanism

The evidence for transgenerational inheritance in humans is assessed through two distinct, yet complementary, methodological approaches. The table below summarizes the core strengths and limitations of each.

Table 1: Comparing Epidemiological and Mechanistic Approaches to Transgenerational Research

| Aspect | Epidemiological Findings (Human Populations) | Mechanistic Proof (Model Organisms) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Evidence | Associative links between ancestral exposures and offspring health outcomes [29] [30] | Direct, causal demonstrations of phenotype transmission and underlying molecular pathways [31] [32] [33] |

| Key Strengths | High human relevance; reflects real-world exposure complexities; can identify novel associations [30] | Controlled environment; establishes causality; enables tissue-specific molecular dissection [31] [32] |

| Major Limitations | Inability to control confounding variables; practical challenges of multi-decade studies; cannot prove causality [30] | Uncertain translatability to humans; often uses supraphysiological exposure doses [29] [30] |

| Primary Data Outputs | Odds ratios, hazard ratios, correlation coefficients | Differentially expressed genes (DEGs), differentially methylated regions (DMRs), and phenotypic measures (e.g., hormone levels, follicle counts) [31] [32] |

A critical analysis of the current literature reveals a clear pattern: while compelling mechanistic proof is accumulating from animal models, direct evidence in humans remains largely epidemiological. For instance, animal studies provide direct evidence that exposure to substances like propylparaben or PM2.5 can induce reproductive abnormalities that persist transgenerationally via identified epigenetic marks [32] [33]. In contrast, human studies often document associations between, for example, EED exposure and declining sperm quality, but cannot definitively establish a transgenerational causal link, highlighting the "black box" of human research [30].

Quantitative Data from Model Organisms

Well-controlled animal studies provide the quantitative foundation for mechanistic claims. The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from recent transgenerational studies, highlighting the specific exposures, models, and robust molecular changes observed.

Table 2: Summary of Quantitative Findings from Key Transgenerational Studies

| Study Model | F0 Exposure | Transgenerational Phenotype in Unexposed Offspring (F2-F3) | Key Molecular Changes (vs. Control) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green-legged Partridgelike Chickens [31] | Synbiotic & Choline (in ovo) | N/A (Molecular endpoints in gonads) | F3 SYNCHs group: 1,897 DEGs, 786 DMRs.F3 SYNCHr group: 2,804 DEGs, 2,880 DMRs. |

| Mouse (Ovarian Reserve) [32] | Propylparaben (PrP) | Decreased Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH); Increased atretic follicles; Decreased primordial follicles. | Hypomethylation of Rhobtb1 promoter in oocytes; Altered methylation in 7253 hypermethylated and 10,117 hypomethylated genes in F2 oocytes. |

| Mouse (Male Hypogonadism) [33] | Real-world PM2.5 (Paternal) | F1 & F2 Males: Low sperm count, reduced testosterone, elevated LH. | Dysregulated sRNAs (miR6240, piR016061) in F0 sperm; Reduced Tet1 expression leading to hypermethylation of testosterone synthesis genes (e.g., Lhcgr, Gnas). |

The data in Table 2 underscores the capacity of ancestral exposures to induce significant and persistent molecular alterations. The chicken model demonstrates a clear cumulative effect with repeated exposure across generations (SYNCHr), resulting in a greater number of epigenetic perturbations [31]. The mouse models directly link specific epigenetic changes—DNA hypomethylation of Rhobtb1 and sRNA-mediated hypermethylation—to tangible, inherited pathological phenotypes [32] [33].

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Investigation

To facilitate the replication and extension of mechanistic research, the following detailed protocols are adapted from recent high-impact studies.

Protocol for a Transgenerational Animal Study

This protocol outlines the core workflow for assessing the transgenerational impact of an in utero exposure in a mammalian model, based on the study of diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) [32].

Title: Transgenerational Assessment of Ovarian Reserve Following Prenatal Exposure Objective: To determine if a prenatal exposure can induce a diminished ovarian reserve phenotype that is transmitted to subsequent, unexposed generations. Experimental Workflow:

Key Materials:

- Animals: ICR or C57BL/6J mice.

- Test Compound: e.g., Propylparaben (PrP), dissolved in appropriate vehicle (e.g., corn oil).

- Dosing: Administer via intraperitoneal injection to pregnant dams during critical windows of fetal development (e.g., fetal sex determination period, E7-E14). Include vehicle-only control group.

- Tissue Collection: Collect ovaries and oocytes at specified time points (e.g., 12 weeks of age) across F1-F3 generations.

Methods:

- Generate F1-F3 Generations: Breed exposed F0 females with unexposed males to produce F1 offspring. The F1 offspring are the first unexposed generation. Breed F1 animals to produce F2, and F2 to produce F3, ensuring no further direct exposure.

- Phenotypic Assessment:

- Ovarian Reserve: Quantify follicles at all stages (primordial, primary, secondary, antral) on histologically stained ovarian sections. Count atretic follicles.

- Hormonal Measurement: Measure serum levels of Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH), 17β-estradiol (E2), and progesterone (P4) via ELISA.

- Estrous Cycle Monitoring: Perform vaginal cytology daily over 2-3 cycles to assess cycle regularity.

- Molecular Analysis:

- DNA Methylation Analysis: Perform single-cell Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (scWGBS) on collected MII oocytes and/or Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) on ovarian tissue to identify transgenerational DMRs [32].

Protocol for Evaluating Sperm Epigenetics in Transgenerational Inheritance

This protocol focuses on the paternal line of inheritance, detailing the analysis of epigenetic marks in sperm, which are hypothesized to carry information across generations [33].

Title: Analysis of Paternal Sperm Epigenome in Transgenerational Inheritance Objective: To characterize small RNA (sRNA) and DNA methylation profiles in the sperm of exposed males and their unexposed offspring to identify potential epigenetic vectors. Experimental Workflow:

Key Materials:

- Animals: Adult male mice (e.g., C57BL/6J).

- Exposure System: Real-ambient PM2.5 exposure system or controlled dosing chamber for other EEDs.

- Sperm Collection Media.

- Reagents: TRIzol for RNA/DNA extraction, kits for sRNA library prep, bisulfite conversion kits.

Methods:

- Paternal Exposure and Sperm Collection: Expose F0 adult males to the environmental stressor (e.g., PM2.5) for a defined period (e.g., 60 days). Collect mature sperm from the cauda epididymis post-exposure.

- Epigenetic Profiling of F0 Sperm:

- sRNA Sequencing: Isolate total RNA from sperm. Construct sRNA libraries for high-throughput sequencing to profile miRNAs and piRNAs. Identify differentially expressed sRNAs [33].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Predict mRNA targets of dysregulated sRNAs (e.g., miR6240, piR016061) using target prediction algorithms.

- Generational Phenotyping and Validation:

- Generate F1 offspring via natural mating or Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) with F0 sperm.

- Assess F1-F3 male offspring for reproductive phenotypes (sperm count, motility, hormone levels, testicular histology).

- Perform WGBS on F1-F3 sperm or testicular tissue to assess DNA methylation status at candidate gene promoters (e.g., Lhcgr, Gnas). Validate gene expression changes via RT-qPCR [33].

Signaling Pathways in Epigenetic Transmission

The mechanistic studies point to converging pathways through which epigenetic information is transmitted and manifests as phenotypic change in subsequent generations. The following diagram synthesizes these pathways, highlighting key molecules and processes.

This pathway illustrates the core hypothesis: an environmental exposure induces epigenetic alterations in the germline of the F0 generation. These alterations, carried by molecules such as sRNAs, DNA methylation, and histones that can escape embryonic reprogramming, are transmitted via gametes. Upon fertilization, they can influence gene expression during embryonic development, ultimately leading to phenotypic changes in the resulting offspring and subsequent generations, even in the absence of direct exposure [34] [32] [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing transgenerational research requires a specific set of reagents and tools. The following table catalogs essential solutions for key experimental procedures in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transgenerational Epigenetics

| Research Reagent / Solution | Primary Function / Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | To convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils for subsequent sequencing, enabling base-resolution mapping of DNA methylation. | Used for Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) of ovarian tissue and single-cell WGBS (scWGBS) of oocytes to identify transgenerational DMRs [32]. |

| sRNA Sequencing Kits | To construct sequencing libraries from small RNA populations (e.g., miRNAs, piRNAs) for profiling and discovery of potential epigenetic vectors in sperm. | Used to identify dysregulated miR6240 and piR016061 in the sperm of PM2.5-exposed males, which target genes like Lhcgr and Nsd1 [33]. |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) Kits | A cost-effective method for analyzing DNA methylation patterns in a subset of genomic regions enriched for CpG islands and promoters. | Employed for DNA methylation analysis in male gonadal tissues of chickens across three generations [31]. |

| Synbiotic & Choline Preparations | Defined nutritional bioactive substances used for in ovo stimulation to study nutriepigenetic effects and transgenerational inheritance. | PoultryStar synbiotic (2 mg/embryo) and choline chloride (0.25 mg/embryo) suspended in saline for in ovo injection [31]. |

| Endocrine Disruptor Chemicals (EDCs) | Well-characterized chemical stressors (e.g., parabens, phthalates) used to model the impact of environmental exposures on the germline. | Propylparaben (PrP) administered to pregnant mice to model transgenerational inheritance of diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) [32]. |

Research Designs and Technical Tools: Profiling Epigenetic Inheritance Across Models

Studying the transgenerational effects of hormone modulation requires meticulously controlled experimental designs that can distinguish true germline epigenetic inheritance from other forms of intergenerational transmission. Optimal animal study designs must account for genetic confounding, in vitro fertilization artifacts, and maternal care influences to ensure valid interpretation of results. This protocol outlines three critical methodological approaches for investigating how parental hormonal exposures affect subsequent generations through epigenetic mechanisms, with particular relevance for endocrine-disrupting chemical research, reproductive biology, and developmental programming studies. The designs emphasized here specifically address germline epigenetic inheritance by controlling for confounding factors such as in utero exposures, maternal care transmission, and direct fetal exposure, thereby enabling researchers to distinguish true transgenerational effects that persist beyond the directly exposed generation.

Experimental Designs for Transgenerational Research

Inbred Strain Selection and Breeding Schemes

The use of inbred animal strains provides genetic uniformity that reduces variability in transgenerational studies, increasing statistical power while controlling for genetic confounding. The Green-legged Partridgelike chicken model demonstrates particular value as an outbred population that may be more sensitive to epigenetic modifications compared to inbred strains, serving as a valuable model for transgenerational epigenetic studies [31]. For rodent models, isogenic strains (e.g., C57BL/6 mice) offer genetic consistency that enhances detection of environmentally-induced epigenetic changes.

Critical breeding scheme considerations:

- Generation-spanning design: Implement at least three generations (F0-F3) to demonstrate true transgenerational inheritance [31] [35]

- Cross-fostering protocols: Utilize foster mothers to control for postnatal maternal effects [35]

- Lineage tracking: Maintain separate maternal and paternal lineages to identify sex-specific inheritance patterns [35]

Table 1: Animal Model Selection Criteria for Transgenerational Studies

| Model System | Genetic Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inbred Rodents | Isogenic background | Reduced variability, controlled genetics | Limited genetic diversity |

| Outbred Chickens | Heterogeneous population | Enhanced epigenetic sensitivity | Higher baseline variability |

| Zebrafish | High fecundity | External development, rapid generation time | Different epigenetic mechanisms |

| Outbred Rodents | Genetic diversity | Human-relevant genetic variation | Requires larger sample sizes |

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) Protocols to Control for Maternal Effects

IVF methodologies enable researchers to distinguish germline transmission from in utero effects by bypassing internal gestation and maternal interactions. A recent mouse model study demonstrated that IVF itself induces transgenerational effects, highlighting both its utility and the necessity for appropriate controls [36].

Comprehensive IVF Protocol:

Step 1: Gamete Collection and Preparation

- Superovulate 4-6 week old female mice with pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) followed by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 48 hours later

- Collect oocytes from ampullae 13-15 hours post-hCG administration

- Isolate sperm from cauda epididymis of sexually mature males (12+ weeks)

- Capacitate sperm in appropriate medium for 30-60 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2

Step 2: In Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Culture

- Co-incubate oocytes with capacitated sperm (1-2×10^6 sperm/mL) for 4-6 hours

- Wash fertilized oocytes to remove excess sperm and culture in KSOM medium

- Culture embryos to blastocyst stage (96 hours post-fertilization)

Step 3: Embryo Transfer and Generation of IVF Cohort

- Transfer 8-12 blastocysts per pseudopregnant recipient (2.5 days post-coitum)

- Generate F1 IVF offspring and naturally-conceived controls in parallel

- Breed F1 animals with wild-type partners to produce F2 generation

- Continue breeding through paternal or maternal lineage to F3 for transgenerational assessment [36]

Critical controls for IVF studies:

- Naturally conceived controls from the same strain

- Sham manipulation groups controlling for embryo handling

- Multiple generation follow-up to assess persistence of effects

Foster Mother Protocols to Control for Postnatal Influences

Cross-fostering methodologies effectively separate in utero exposure effects from postnatal maternal care influences, which is particularly crucial in transgenerational studies where maternal behavior can itself be modified by experimental manipulations and transmitted to subsequent generations [35].

Standardized Foster Protocol:

Step 1: Preparation of Foster Dams

- Time naturally birthing dams to be within 24 hours of experimental dams

- Select foster mothers with proven maternal care history when possible

- Acclimate foster dams to single housing 3-5 days pre-parturition

Step 2: Cross-Fostering Procedure

- Within 12-24 hours post-birth, carefully remove foster dam from nest

- Randomly redistribute pups between biological and foster dams, maintaining equal litter sizes

- Gently coat pups with soiled bedding from foster dam's cage to standardize olfactory cues

- Monitor maternal acceptance for 30 minutes continuously, then periodically for 24 hours

Step 3: Maternal Behavior Assessment