Mastering MeSH: The Ultimate Guide to Systematic Keyword Research for Biomedical Professionals

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to master the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus for effective literature retrieval.

Mastering MeSH: The Ultimate Guide to Systematic Keyword Research for Biomedical Professionals

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to master the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus for effective literature retrieval. It covers foundational concepts, practical application methods, advanced troubleshooting for common search challenges, and validation techniques to ensure search accuracy and completeness. By integrating MeSH terms with keyword strategies, readers will learn to construct robust, systematic searches that account for evolving terminology, maximize recall of relevant studies, and enhance the rigor of evidence-based research and development.

What is MeSH? Building Your Foundational Knowledge for Effective Searching

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) is a controlled and hierarchically-organized vocabulary thesaurus produced by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) [1]. It serves as a foundational resource for indexing, cataloging, and searching biomedical and health-related information across numerous databases, including MEDLINE/PubMed and the NLM Catalog [1]. By providing a standardized set of terminology, MeSH addresses the challenge of variant terminology in biomedical literature, ensuring that content is discoverable regardless of the specific words used by authors [2]. For instance, a search for the MeSH descriptor "Myocardial Infarction" will systematically retrieve records that use synonymous terms such as "heart attack" or "acute myocardial injury" [2]. This functionality makes MeSH an indispensable tool for rigorous biomedical information retrieval and scientific keyword research.

The Structural Anatomy of MeSH

The MeSH vocabulary is built upon a sophisticated three-tiered structure that exists within a single Descriptor record: Descriptor, Concept, and Term [3]. This structure allows for precise attribution of data elements and establishes clear relationships between different linguistic expressions of the same idea.

The Three-Tiered Structure

- Descriptor: A Descriptor is the top-level category in a MeSH record, representing a distinct biomedical concept and serving as the primary subject heading for indexing and searching. Each record has a single Preferred Concept, whose Preferred Term is also the name of the Descriptor itself [3]. Example: "Cardiomegaly" [3].

- Concept: Within a Descriptor, strictly synonymous terms are grouped into categories called Concepts. Each Concept has its own Preferred Term, which serves as the name for that Concept. A single Descriptor record can consist of multiple Concepts, which may have relationships to one another (e.g., a narrower concept) [3]. Example: Within the "Cardiomegaly" Descriptor, there are "Cardiomegaly" and "Cardiac Hypertrophy" Concepts [3].

- Term: Terms are the individual words or phrases that make up each Concept. These include the Preferred Term for the Concept along with various entry terms (synonyms). All terms within a single Concept are considered strictly synonymous with one another [3]. Example: The "Cardiac Hypertrophy" Concept contains the terms "Cardiac Hypertrophy" (Preferred) and "Heart Hypertrophy."

Table: MeSH Structure Example for "AIDS Dementia Complex" Descriptor

| Descriptor | Concept | Term |

|---|---|---|

| AIDS Dementia Complex | AIDS Dementia Complex (Preferred Concept) | AIDS Dementia Complex (Preferred Term) |

| Acquired-Immune Deficiency Syndrome Dementia Complex | ||

| AIDS-Related Dementia Complex | ||

| HIV Encephalopathy (Narrower Concept) | HIV Encephalopathy (Preferred Term) | |

| AIDS Encephalopathy | ||

| HIV-1-Associated Cognitive Motor Complex (Narrower Concept) | HIV-1-Associated Cognitive Motor Complex (Preferred Term) | |

| HIV-1 Cognitive and Motor Complex |

Hierarchical Organization: The MeSH Tree Structures

Beyond the internal structure of individual records, MeSH organizes Descriptors into broader hierarchical categories known as Tree Structures [3]. This system groups related concepts from broad categories to increasingly specific ones, arranged under 16 main branches such as Anatomy, Diseases, Chemical Compounds, and Analytical Methods [4]. The Tree Structures enable users to explore related concepts and perform comprehensive searches that include all narrower terms in the hierarchy [2].

MeSH in Practice: Applications and Methodologies

Indexing and Searching with MeSH

MeSH terms are applied to citations in MEDLINE/PubMed through an automated indexing process, with human indexers checking the quality of selected sets [2]. Each article is typically indexed with 10-15 MeSH terms [4], which allows for precise information retrieval. Two primary methods exist for finding relevant MeSH terms:

- Using MeSH Terms from a Known Article: When a relevant article is identified in PubMed, its associated MeSH terms are displayed at the bottom of the citation record. These terms can be selected to execute a new search for articles sharing the same indexing [5].

- Searching the MeSH Thesaurus: PubMed's MeSH database allows users to search directly for concepts. The system provides definitions, available subheadings (qualifiers), and shows the term's position in the hierarchical tree structure, enabling identification of broader, narrower, and related terms [2] [5].

NLM updates the MeSH vocabulary annually in response to emerging scientific concepts, taxonomic changes, and ethical considerations [6]. For 2025, one of the most significant expansions involves Artificial Intelligence, with dozens of new MeSH Descriptors added within this conceptual domain [6] [7]. These continuous updates ensure the vocabulary remains current with scientific progress.

Experimental Protocol: MeSH Term Analysis for Research Trend Identification

Research by scholarly analysts has demonstrated that comparative analysis of MeSH term frequencies can reveal evolving scientific trends [4]. The following methodology provides a framework for conducting such analyses.

Objective: To identify MeSH terms that characterize specialized research areas and detect topics with significantly changing publication frequencies over time.

Materials and Reagents:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for MeSH Trend Analysis

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE/PubMed Database | Primary source of biomedical literature abstracts and associated MeSH terms [4]. |

| PubMed API (e.g., Scanbious) | Programmatic interface for retrieving publication identifiers (PMIDs) and their associated MeSH terms based on specific queries [4]. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Platform for performing statistical tests, multiple comparison corrections, and data visualization [4]. |

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Define a target sample (

Sample 1) of publications representing a specialized research area (e.g., personalized medicine) using a specific PubMed queryQ(t)[4]. - Define a background control sample (

Sample 2) of publications from a broader field (e.g., general medicine) for comparison [4]. - Use the PubMed API to retrieve lists of PMIDs for both samples and their associated MeSH terms.

- Define a target sample (

Data Processing:

- Calculate the relative frequency of each MeSH term for each sample and year:

PMi/Nc(target sample) andGMi/Nt(control sample), wherePMiandGMiare counts of papers annotated by the term, andNcandNtare total papers in the respective samples for the year [4]. - Form MeSH-term frequency vectors for each sample.

- Calculate the relative frequency of each MeSH term for each sample and year:

Statistical Analysis:

- For each term and year, compare relative frequencies between samples using a proportions test (e.g.,

prop.testin R) [4]. - Apply False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons [4].

- Aggregate p-values across years (e.g., 2009-2018) using Fisher's method to obtain a final estimate of significance for differences in term usage [4].

- Calculate the effect size as a log ratio:

logratio = log2(PMi/GMi). A positive value indicates higher frequency in the target sample [4]. - Analyze temporal trends in term frequency using the non-parametric Mann-Kendall test to identify terms with consistently increasing or decreasing usage [4].

- For each term and year, compare relative frequencies between samples using a proportions test (e.g.,

Several specialized tools facilitate effective keyword research using the MeSH vocabulary, each designed for specific use cases from automated term identification to manual vocabulary exploration.

Table: MeSH Research Tools and Resources

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Keyword Research |

|---|---|---|

| MeSH on Demand | Automatically identifies relevant MeSH terms from user-provided text (e.g., an abstract) using natural language processing [8]. | Provides a starting point for identifying potential keywords by analyzing a draft abstract. Results are machine-generated and should be verified [8]. |

| MeSH Browser | Allows direct searching and browsing of the MeSH thesaurus, including Scope Notes, Annotations, Entry Terms, and Tree Structures [1] [8]. | Enables precise lookup of terms, verification of definitions, and exploration of broader/narrower concepts via the hierarchy [8]. |

| Annual MeSH Update Reports | Details all changes (additions, modifications, replacements, deletions) made to the MeSH vocabulary each year [9]. | Critical for maintaining current search strategies and identifying newly available terms for emerging topics (e.g., AI concepts in 2025) [9] [6]. |

Strategic Considerations for Researchers

When incorporating MeSH into keyword research for drug development and scientific investigation, professionals should consider several strategic factors:

Vocabulary Dynamics: MeSH is a living vocabulary that undergoes significant annual updates. The 2025 update introduced approximately 200 new descriptors, with a substantial portion related to Artificial Intelligence, reflecting shifting scientific priorities [6] [7]. Researchers must consult annual update reports to ensure their keyword strategies incorporate newly available terminology.

Retrieval Limitations: When new MeSH terms are introduced, NLM typically does not retroactively re-index existing MEDLINE citations [9] [6]. Consequently, searches limited to a new MeSH term will primarily retrieve citations indexed after its introduction. Comprehensive searches must incorporate previous indexing terms or consider broader terms in the MeSH hierarchy to capture relevant earlier literature [9].

Integration with Related Vocabularies: MeSH exists within a broader ecosystem of biomedical terminologies maintained by NLM. For drug development professionals, RxNorm provides a standardized nomenclature for clinical drugs and supports e-prescribing, formulary development, and medication history applications [1]. The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) Metathesaurus integrates concepts from over 150 vocabulary sources, including MeSH, facilitating connections across different terminological systems [1].

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) is a comprehensive controlled vocabulary thesaurus created and updated by the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) to index journal articles, books, and other resources in the life sciences [10]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering MeSH's structure is not merely an academic exercise—it is a fundamental skill for conducting precise, reproducible, and comprehensive literature searches. Effective keyword research using MeSH ensures that queries capture all relevant conceptual variations, accounts for hierarchical relationships, and leverages standardized terminology, thereby maximizing retrieval efficiency and minimizing the risk of missing critical scientific evidence. This technical guide deconstructs the core components of MeSH—hierarchies, tree structures, and scope notes—to provide a robust methodological framework for integrating this powerful thesaurus into systematic research practices.

The Architectural Blueprint: Descriptor Hierarchy and Tree Structures

The Hierarchical Organization of Descriptors

At its core, the MeSH vocabulary is organized into a polyhierarchical structure where each descriptor (or subject heading) resides within a set of categories and subcategories [11]. This structure arranges descriptors from the most general to the most specific across up to thirteen hierarchical levels, creating a branching architecture often referred to as "trees" [11]. The hierarchy encompasses sixteen top-level categories, each identified by an alphabetic code, which provide the foundational classification for all subsequent terms (see Table 1: Top-Level MeSH Categories) [10].

Table 1: Top-Level MeSH Categories [10]

| Category Code | Category Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A | Anatomy | Organisms, tissues, cells, and subcellular structures |

| B | Organisms | Live entities such as plants, animals, and microorganisms |

| C | Diseases | Pathological conditions and diseases |

| D | Chemicals and Drugs | Chemical substances, drugs, and pharmaceutical agents |

| E | Analytical, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Techniques, and Equipment | Procedures, equipment, and investigative methods |

| F | Psychiatry and Psychology | Mental processes and behaviors |

| G | Phenomena and Processes | Biological, chemical, and physical phenomena |

| H | Disciplines and Occupations | Scientific disciplines and professional fields |

| I | Anthropology, Education, Sociology and Social Phenomena | Social sciences and educational aspects |

| J | Technology, Industry, and Agriculture | Applied sciences, technology, and industrial applications |

| K | Humanities | Arts, history, and philosophy of medicine |

| L | Information Science | Information management, storage, and retrieval |

| M | Named Groups | Specific populations and demographic groups |

| N | Health Care | Healthcare services, facilities, and systems |

| V | Publication Characteristics | Publication types and formats |

| Z | Geographicals | Geographic locations |

Tree Numbers and Polyhierarchy

The position of a MeSH descriptor within the hierarchy is designated by a systematic label known as a tree number [11] [12]. A single descriptor frequently appears in multiple locations within the hierarchical trees—a concept known as polyhierarchy—and therefore can possess multiple tree numbers [10] [12]. For instance, the descriptor "Digestive System Neoplasms" has the tree numbers C06.301 and C04.588.274, locating it within both the "Digestive System Diseases" tree and the "Neoplasms By Site" tree [10]. This multi-parentage allows for complex concepts to be appropriately classified under multiple broader topics, a critical feature for comprehensive retrieval. The tree numbers themselves are subject to change with annual MeSH updates and serve primarily as locators within the structure without intrinsic numerical significance [11].

The following diagram visualizes the hierarchical relationships and polyhierarchical nature of MeSH descriptors using the example of "Eye" and related terms, which belong to multiple parent trees.

Figure 1: MeSH Hierarchical Tree Structure. This diagram illustrates the polyhierarchical placement of "Eye" (A09.371) and its narrower terms, showing how "Eyelids" and "Eyebrows" can be accessed through multiple broader parent trees (A01 and A09).

The Principle of Most Specific Indexing

A fundamental principle in using MeSH for indexing and searching is to select the most specific descriptor available to represent a concept [11]. This practice, known as specificity, ensures that articles are categorized under the most precise relevant term. For example, an article about Streptococcus pneumoniae will be indexed under that specific descriptor rather than the broader term "Streptococcus" [11]. This principle directly impacts search strategy: searchers must consult the trees to identify whether more specific terms exist beneath a broader heading of interest to ensure complete retrieval. PubMed's default search behavior, known as "explode," automatically includes all narrower terms in the hierarchy when a descriptor is searched, but this can be disabled for precision when needed [10] [13].

Defining and Contextualizing Concepts: The Role of Scope Notes

Scope Notes for Descriptors

Qualifiers and Their Scope Notes

Beyond main descriptors, MeSH employs a set of qualifiers (also known as subheadings) that can be appended to descriptors to refine the focus on a particular aspect of the subject [10] [14]. There are 83 such qualifiers, each with its own detailed scope note that provides explicit instructions on its proper application [10] [14]. For instance, the qualifier "/adverse effects" is defined for use "with drugs, chemicals, or biological agents... for adverse effects or complications of... procedures," while "/blood" is used "for the presence or analysis of substances in the blood" [14]. Not all descriptor/qualifier combinations are permitted; the system only allows pairings that are conceptually meaningful [10].

Table 2: Selected MeSH Qualifiers and Scope Notes [14]

| Qualifier Name | Abbreviation | Short Form | Scope Note Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administration & Dosage | AD | ADMIN | Dosage forms, routes, frequency, duration, and effects thereof. |

| Adverse Effects | AE | ADV EFF | Harmful effects of drugs, chemicals, or procedures in normal use. |

| Agonists | AG | AGON | Substances with affinity and intrinsic activity at a receptor. |

| Analysis | AN | ANAL | Identification or quantitative determination of a substance; excludes tissue analysis. |

| Anatomy & Histology | AH | ANAT | Normal descriptive anatomy and histology of organs and tissues. |

| Antagonists & Inhibitors | AI | ANTAG | Substances that counteract the effects of other agents. |

| Biosynthesis | BI | BIOSYN | Anabolic formation of substances in organisms, cells, or subcellular fractions. |

| Chemical Synthesis | CS | CHEM SYN | Chemical preparation of molecules in vitro. |

| Drug Therapy | DT | DRUG THER | Treatment of disease with drugs, chemicals, or antibiotics. |

| Epidemiology | EP | EPIDEMIOL | Disease distribution, causative factors, and attributes in defined populations. |

| Genetics | GE | GENET | Hereditary mechanisms and genetic basis of normal and pathological states. |

| Metabolism | ME | METAB | Biochemical changes and metabolism; includes catabolic changes for chemicals. |

| Pharmacology | PK | PHARMACOKIN | Mechanism, dynamics, and kinetics of substances in the body. |

| Therapy | TH | THER | Therapeutic interventions excluding drug therapy and radiotherapy. |

Methodologies for Leveraging MeSH Structure in Keyword Research and Search Execution

Experimental Protocol: Building a Precise PubMed Search Using the MeSH Database

This methodology outlines the systematic process for constructing a highly targeted PubMed search query using the MeSH database's hierarchical structure and qualifiers.

Step 1: Concept Identification and Initial Terminology Mapping - Begin by deconstructing your research question into core conceptual components. For each concept, enter potential keywords into the PubMed search bar and execute a preliminary search. Immediately navigate to the "Search Details" panel to observe PubMed's Automatic Term Mapping (ATM), which reveals how your natural language terms were translated into official MeSH descriptors and entry terms [10]. This step identifies the primary MeSH terms for your concepts and reveals synonym relationships.

Step 2: Hierarchical Exploration and Specificity Validation - For each identified MeSH descriptor, access the MeSH Database record. Critically examine the "Tree Structures" section (often denoted by section E or F in the database interface) to visualize the term's position in the hierarchy [13]. Determine if the concept is represented by the most specific descriptor available. If more specific (narrower) terms exist in the trees and are relevant to your research, incorporate them into your search strategy to enhance precision.

Step 3: Application of Qualifiers and Search Restrictions - Within the MeSH Database record for each descriptor, review the list of allowable qualifiers (subheadings) [13]. Select qualifiers that best represent the aspect of the concept you are investigating (e.g., "/drug therapy" for a disease, "/therapeutic use" for a drug). Use the scope notes for qualifiers (see Table 2) to ensure correct application [14]. Optionally, apply search restrictions such as "[Majr]" to restrict retrieval to articles where the term is a major topic, or "[Mesh:NoExp]" to prevent automatic explosion of the hierarchy [13].

Step 4: Search Construction and Execution - Use the MeSH Database's "Search Builder" tool to add your refined terms, complete with selected qualifiers and restrictions, to a structured query [13]. Combine multiple concepts using the Boolean operator "AND" to ensure results address all aspects of your research question. Review the final search string in the builder for accuracy before clicking "Search PubMed" to execute the query.

Experimental Protocol: Tracking Vocabulary Changes and Updates

MeSH is a dynamic vocabulary updated annually, necessitating proactive monitoring for sustained search accuracy. This protocol provides a methodology for tracking these changes.

Step 1: Monitor Official NLM Communication Channels - Regularly consult the NLM Technical Bulletin, specifically the "Annual MeSH Processing" article published towards the end of each year, which details the upcoming changes to the vocabulary, including new descriptors, deleted terms, and structural modifications [9]. This is the primary source for authoritative update information.

Step 2: Utilize MeSH Update Reports - Access the structured "MeSH Update" reports provided by NLM, which are available in various formats (CSV, PDF, HTML) and provide detailed, exportable data on additions, deletions, and modifications to descriptors and Supplementary Concept Records (SCRs) [9]. Integrate review of these reports into your pre-search workflow, especially after the annual MeSH release.

Step 3: Account for Retroactive and Non-Retroactive Indexing - Understand NLM's indexing policies. Typically, new MeSH terms are not applied retroactively to older citations [9]. Therefore, a search for a new term will only retrieve articles indexed after its introduction. For comprehensive historical searches, consult the "Previous Indexing" information in the MeSH record to identify the terms previously used for that concept and incorporate them into your search strategy [9] [13].

Table 3: Key Resources for MeSH-Based Research [15] [9] [13]

| Resource Name | Function | Access Point |

|---|---|---|

| MeSH Database | The primary tool for browsing the thesaurus, viewing tree structures, scope notes, and entry terms, and building targeted search queries. | Accessed via the PubMed interface or directly at the NLM MeSH website. |

| NLM Technical Bulletin | Provides official announcements and detailed articles on annual MeSH updates, new features, and changes to indexing policies. | Published online by the National Library of Medicine. |

| MeSH Update Reports | Downloadable, detailed reports (in CSV, JSON, RDF, XML) listing all specific changes (additions, deletions, modifications) made during the annual update cycle. | Found via the NLM Data Discovery catalog or linked from the Technical Bulletin. |

| PubMed Search Details | A feature that displays how a submitted search query was translated by PubMed's Automatic Term Mapping (ATM), revealing the MeSH terms and logic actually used. | Available under the "Search Details" box on the search results page after executing a PubMed query. |

| MeSH Qualifiers with Scope Notes | A complete reference list of all 83 qualifiers alongside their full scope notes, providing essential guidance for their correct application. | Hosted on the NLM website as a dedicated page. |

The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus is a controlled and hierarchically-organized vocabulary produced by the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM). It serves as a critical tool for indexing, cataloging, and searching biomedical and health-related information across databases like MEDLINE/PubMed and the NLM Catalog [1] [10]. A MeSH record structures biomedical concepts into a standardized format, enabling precise information retrieval. For researchers conducting keyword research, understanding the core components of a MeSH record—Entry Terms, Subheadings (Qualifiers), and Tree Numbers—is fundamental to developing effective and comprehensive search strategies. This guide deconstructs these elements within the context of a systematic approach to keyword investigation.

Core Components of a MeSH Record

Entry Terms: The Gateway to Controlled Vocabulary

Entry Terms, also known as "See cross-references," are the synonyms, near-synonyms, alternate forms, and other closely related terms listed within a MeSH record [16]. They function as a bridge between the natural language a researcher might use and the preferred, controlled vocabulary of the MeSH descriptor.

- Function and Role: The primary function of Entry Terms is to enrich the thesaurus, guiding both indexers and searchers to the preferred MeSH heading. They are generally used interchangeably with the preferred descriptor for cataloging, indexing, and retrieval [16] [17].

- Impact on Searching: In PubMed, a search using an entry term automatically triggers the system's Automatic Term Mapping (ATM), which translates the entered phrase into the corresponding MeSH descriptor for the search. This ensures that relevant articles are retrieved even when the searcher does not know the precise MeSH term [15] [10]. For instance, a search for "Heart Arrest" will also map from entry terms like "Arrest, Heart" and "Asystole" [16].

Table: Entry Term Examples for a MeSH Descriptor

| MeSH Descriptor (Preferred Term) | Example Entry Terms |

|---|---|

Heart Arrest |

Arrest, Heart; Cardiac Arrest; Asystole; Cardiorespiratory Arrest [16] |

Independent Living |

Community Dwelling [15] |

Subheadings (Qualifiers): Refining the Focus

Qualifiers, often called Subheadings, are a set of standard terms used in conjunction with MeSH descriptors to narrow the focus of a topic to a specific aspect [17] [10]. There are 78 topical qualifiers available for indexing [17].

- Function and Role: Qualifiers allow for the precise description of an article's content. They afford a convenient means of grouping citations concerned with a particular facet of a subject [17]. For example, while

Liveris a broad descriptor,Liver/drug effectsspecifies that the article is about the effect of drugs on the liver, andLiver/surgeryfocuses on surgical aspects of the liver. - Application in Keyword Research: Using qualifiers in a PubMed search strategy helps filter results to the most relevant sub-topic, significantly increasing the precision of keyword research. Not all descriptor/qualifier combinations are permitted, as some may be semantically meaningless [10].

Table: Common MeSH Subheadings (Qualifiers) and Their Applications

| Subheading | Abbreviation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects | AE | Aspirin/adverse effects - Side effects of a drug. |

| Drug therapy | DT | Asthma/drug therapy - Use of drugs to treat a disease. |

| Epidemiology | EP | Influenza, Human/epidemiology - Disease occurrence. |

| Metabolism | ME | Glucose/metabolism - Biochemical transformations. |

| Surgery | SU | Appendicitis/surgery - Surgical procedures. |

Tree Numbers: Mapping the Hierarchical Structure

Tree Numbers are systematic labels that represent a descriptor's location within the MeSH hierarchical tree structures [10]. A single descriptor may appear in multiple locations in the hierarchy, and therefore can have several tree numbers.

- Function and Role: The tree structures organize MeSH descriptors from broader (parent) to narrower (child) concepts across sixteen top-level categories, denoted by letters like A (Anatomy), B (Organisms), C (Diseases), and D (Chemicals & Drugs) [10]. Tree numbers are subject to change as MeSH is updated annually, but each descriptor also carries a unique alphanumerical ID that remains constant [10].

- Application in Keyword Research: The hierarchical structure is leveraged in PubMed through the "Explode" feature. Searching a MeSH term with its children included (exploding) ensures a comprehensive search by automatically including all more specific terms nested beneath it in the tree [10]. This is crucial for ensuring breadth in keyword research.

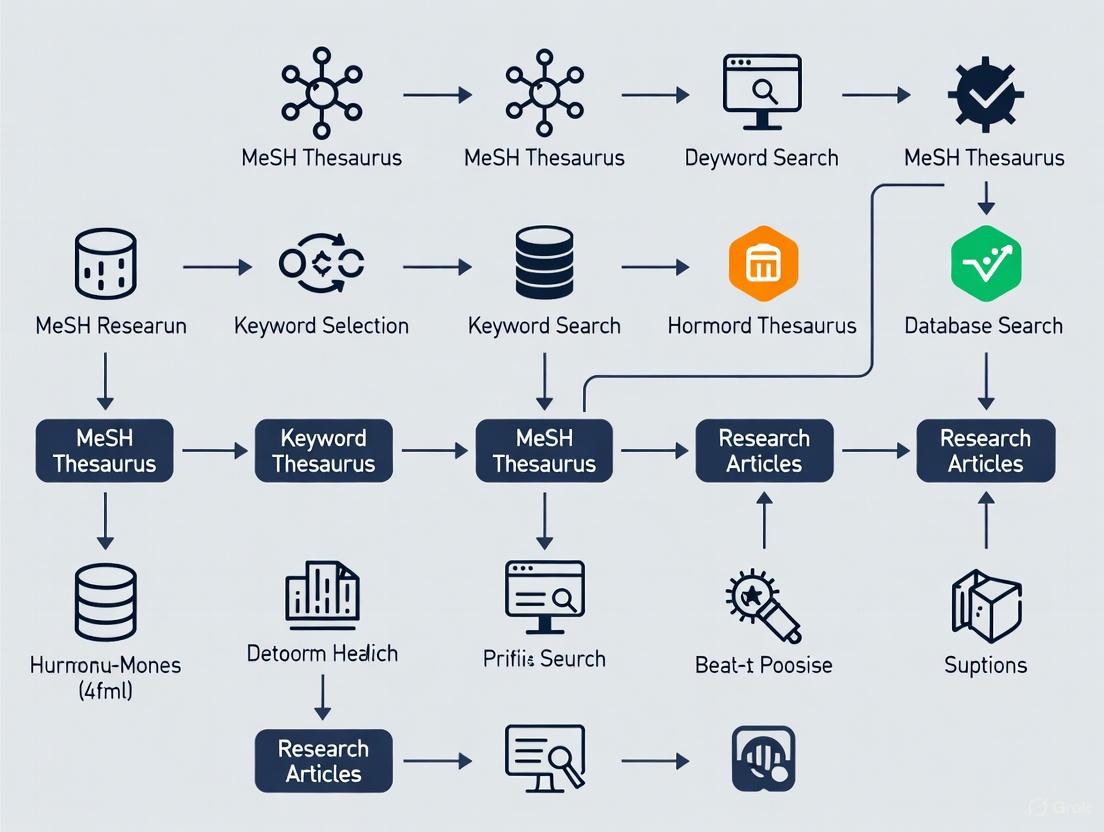

Figure 1: Logical relationships between core MeSH record components and system functions.

The MeSH thesaurus is dynamically updated to reflect progress in medicine and science. The quantitative data below from the 2025 release provides a snapshot of the scale and evolution of the vocabulary, which directly impacts the comprehensiveness of keyword research [15].

Table: MeSH 2025 Vocabulary Statistics

| Record Type | Total Count | New in 2025 | Notable Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Headings (Descriptors) | 30,956 | 192 | New terms in Phenomena/Processes (G) and Information Science (L) [15]. |

| Supplementary Concept Records (SCRs) | 323,939 | 1,001 | Includes chemicals, drugs, and rare diseases; updated nightly [15] [17]. |

| Publication Types | Not specified | SCOPING REVIEW added, NETWORK META-ANALYSIS becomes a Publication Type [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Utilizing MeSH Components for Systematic Keyword Research

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for using MeSH record components to conduct a systematic and reproducible literature search, forming the core of effective keyword research.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for MeSH-Based Research

Table: Key Digital Tools for MeSH-Based Keyword Research

| Tool Name | Function in Keyword Research |

|---|---|

| MeSH Database (NLM) | The primary tool for identifying relevant descriptors, their entry terms, tree numbers, and subheadings. |

| PubMed Search Interface | The platform where search strategies are executed, leveraging Automatic Term Mapping and explodes. |

| NLM Technical Bulletin | Source for updates on annual MeSH changes, new terms, and discontinued headings [15]. |

Methodology

Concept Identification and Vocabulary Mining:

- Break down the research topic into core conceptual components.

- For each concept, use the MeSH Database to search for potential main headings. Take note of the Entry Terms listed, as these represent valuable alternative keywords and phrases that will be automatically mapped in PubMed [16].

Hierarchical Exploration and Strategy Formulation:

- For each identified main heading, examine its Tree Numbers and location within the MeSH hierarchy.

- Decide whether an "Explode" search is appropriate. If the concept is broad and should include all specific child terms, use the explode function. If the concept is very specific, a non-exploded search may be more precise [10].

Precision Refinement with Subheadings:

- Determine if any aspect of a concept can be refined using Subheadings. For a question about the drug therapy of a disease, applying the

/drug therapysubheading to the disease descriptor will filter out articles focused on, for instance, the genetics or surgery of that disease [17].

- Determine if any aspect of a concept can be refined using Subheadings. For a question about the drug therapy of a disease, applying the

Search String Assembly and Execution:

- Combine the selected descriptors (exploded or not) with their relevant subheadings using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT).

- Execute the search in PubMed.

Validation and Iterative Refinement:

- Check the "Search Details" in PubMed to confirm how your query was translated via Automatic Term Mapping. This reveals which MeSH terms and entry terms were used [10].

- Review the results and refine the search strategy iteratively by adding, removing, or modifying terms based on relevance.

Figure 2: Workflow for building a systematic literature search using MeSH components.

Case Study: Keyword Research on "Aging in Place"

The 2025 MeSH update provides a clear example of how the vocabulary evolves and impacts searching. Previously, the phrase "Aging in Place" was an Entry Term for the main heading Independent Living [15]. A PubMed search for Aging in Place would trigger Automatic Term Mapping and search for the MeSH term Independent Living, yielding approximately 52,498 results [15].

- Post-2025 Update:

Aging in Placehas been promoted to the status of a Main Heading, withCommunity Dwellingas its entry term [15]. - Impact on Search: The same search for

Aging in Placenow triggers the new, more specific MeSH term. Searchers may notice a drop in result count as the search is no longer broadened by the parent termIndependent Living. This change benefits keyword research by enabling more precise retrieval of articles specifically about aging in place [15]. - Research Strategy:

- Pre-2025: A precise search required knowing that

Aging in Placemapped toIndependent Living. - Post-2025: A search for the phrase automatically maps to the specific heading. For comprehensive research, a searcher might now use an "OR" operation to combine the new

Aging in Placeterm with the broaderIndependent Livingterm to capture the full scope of literature. This case highlights the importance of checking the MeSH database for current relationships.

- Pre-2025: A precise search required knowing that

In the complex landscape of biomedical literature retrieval, researchers face significant challenges in navigating the vast and inconsistent terminology of scientific publications. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), the National Library of Medicine's controlled vocabulary, provides a sophisticated solution to the problem of keyword variability by establishing a standardized framework for information indexing and retrieval. This technical guide examines the structural foundations of MeSH and demonstrates through quantitative analysis how its hierarchical organization and vocabulary control mechanisms enhance search precision and recall compared to traditional text-word strategies. Framed within the context of systematic keyword research methodology, this whitepaper provides drug development professionals and researchers with evidence-based protocols for integrating MeSH into comprehensive literature retrieval workflows, supported by experimental data and practical implementation frameworks.

Biomedical researchers navigating today's literature face a fundamental retrieval problem: the same concepts are described using different terminology across publications. This keyword variability stems from multiple factors including author preferences, disciplinary conventions, and evolving terminology. Without a standardized vocabulary, researchers struggle to comprehensively locate relevant literature, potentially missing critical studies and introducing selection bias into their research. The PubMed database alone contains over 36 million citations with approximately 1 million new additions annually [18], making comprehensive literature retrieval without systematic tools virtually impossible.

MeSH addresses this challenge through its controlled vocabulary of over 27,000 hierarchically-organized terms [18]. This system provides uniformity and consistency to the indexing, cataloging, and searching of biomedical information across NLM databases [19]. For example, a search for the MeSH term "telemedicine" automatically includes synonyms such as "mobile health," "mhealth," "telehealth," and "ehealth" [19], effectively searching for meaning rather than merely matching text strings. This conceptual approach to information retrieval forms the foundation of effective literature searching for evidence-based medicine and systematic reviews.

MeSH Structure and Vocabulary Control Mechanisms

Hierarchical Organization and Semantic Relationships

The MeSH vocabulary is organized hierarchically from broader to narrower terms across 16 main categories, creating a tree structure that enables both specific and comprehensive searching. For instance, the term "Heart Diseases" encompasses narrower terms including "Arrhythmias, Cardiac," which further includes "Atrial Fibrillation" [20]. This arrangement allows searchers to leverage the hierarchy based on their information needs—searching broader terms to capture all relevant literature or narrower terms for precise retrieval.

MeSH incorporates several semantic relationships that enhance retrieval effectiveness:

- Entry Terms: Synonyms and related phrases that direct users to the preferred MeSH term (e.g., "heart attack" maps to "myocardial infarction") [21]

- Scope Notes: Definitions and usage guidelines that clarify a term's meaning and application

- Cross-References: Links to related terms that assist in locating the most appropriate heading

- Subheadings: Qualifiers that allow searching for specific aspects of a subject (e.g., "drug therapy" or "surgery") [20]

Vocabulary Control and Standardization Processes

MeSH employs rigorous vocabulary control mechanisms to maintain consistency. Human indexers assign approximately 5-15 MeSH terms to each article in MEDLINE, describing the primary concepts discussed [21]. When no specific heading exists for a concept, indexers use the closest available general heading, ensuring consistent application across the literature. The National Library of Medicine annually updates MeSH to reflect scientific advancements, with new terms added and existing terms modified or retired based on emerging terminology and user suggestions [1].

Quantitative Analysis: MeSH vs. Text-Word Retrieval Performance

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A 2022 study compared the effectiveness of MeSH-term versus text-word searching using rigorous bibliometric measurements [22]. Researchers employed the relevant recall method to evaluate search strategies for literature on psychosocial aspects of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. The experimental protocol consisted of:

- Gold Standard Development: Identification and evaluation of 3,162 resources to form a validated set of 1,521 relevant articles

- Search Strategy Formulation: Creation of parallel MeSH-term and text-word search strategies for the same research question

- Performance Measurement: Calculation of recall and precision metrics for both strategies

- Statistical Analysis: Comparison of results to determine significant differences in retrieval effectiveness

Recall was defined as the number of relevant citations retrieved divided by the total number of relevant citations, while precision was calculated as the number of relevant citations retrieved divided by the total number of citations retrieved [22].

Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Recall and Precision Comparison of Search Strategies

| Search Strategy | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | Complexity Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| MeSH-term | 75 | 47.7 | High |

| Text-word | 54 | 34.4 | Low |

Table 2: Database Coverage in Systematic Reviews

| Database Metric | Percentage |

|---|---|

| References found in a single database | 16% |

| Recall with multiple databases | 98.3% |

| Systematic reviews with incomplete searches | 60% |

The experimental results demonstrate that the MeSH-term strategy yielded significantly higher recall (75% vs. 54%) and precision (47.7% vs. 34.4%) compared to text-word searching [22]. This performance advantage comes with increased complexity in search design and execution, requiring greater expertise to implement effectively. The data further indicates that searching multiple databases improves comprehensive retrieval, with Embase alone contributing 132 unique references in systematic reviews [18].

Figure 1: MeSH vs. Text-Word Search Performance Comparison

MeSH Implementation Framework: Protocols for Effective Retrieval

MeSH Term Identification and Selection Methodology

Implementing an effective MeSH-based search strategy requires systematic term identification and selection:

- MeSH Database Exploration: Access the MeSH database via PubMed homepage under "Explore" [21]

- Concept Mapping: Input conceptual keywords to identify corresponding MeSH terms and entry terms

- Hierarchy Examination: Review broader and narrower terms in the MeSH tree structure to determine appropriate term specificity [20]

- Subheading Selection: Identify applicable subheadings to focus searches on specific aspects of a topic

- Term Validation: Verify term selection using relevant articles' assigned MeSH terms [19]

For emerging concepts without dedicated MeSH terms, researchers should identify the closest broader terms while supplementing with text-words to ensure comprehensive coverage [19].

Search Strategy Formulation Workflow

Table 3: MeSH Search Formulation Protocol

| Step | Action | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conceptual analysis of research question | Defined concepts for searching |

| 2 | MeSH term identification for each concept | Controlled vocabulary terms |

| 3 | Synonym and entry term collection | Supplementary text-words |

| 4 | Boolean logic application | Combined search strategy |

| 5 | Results evaluation and strategy refinement | Optimized search query |

Figure 2: MeSH Search Strategy Development Workflow

MeSH-Enhanced Keyword Research for Drug Development

Domain-Specific Applications

Drug development professionals can leverage MeSH for comprehensive competitor intelligence, clinical trial landscape analysis, and mechanism of action investigations. Specific applications include:

- Drug Profiling: Utilizing MeSH pharmacological action terms to identify literature about drug classes and mechanisms

- Therapeutic Area Mapping: Employing disease hierarchy terms to understand research density across related conditions

- Biomarker Discovery: Applying technique and diagnostic heading combinations to locate validation studies

- Adverse Event Monitoring: Combining drug subheadings with toxicity terms for safety surveillance

The integration of NCBI taxonomy identifiers into MeSH enhances retrieval of organism-specific research relevant to preclinical studies [23]. This integration facilitates precise searching for literature involving specific pathogens, model organisms, or biological materials used in drug development.

Advanced Integration with Research Databases

While PubMed/MedLINE remains the primary MeSH-enabled database with 100% coverage in systematic reviews [18], researchers should implement cross-database searching to minimize bias and maximize retrieval. Key databases include:

- Embase: Particularly strong for pharmacological and European literature, with unique record coverage

- Cochrane Library: Essential for evidence-based medicine and systematic reviews

- Scopus: Multidisciplinary coverage with robust citation analysis tools

- CINAHL: Valuable for nursing and allied health literature

Table 4: Database Integration for Comprehensive Retrieval

| Database | Unique Contribution | MeSH Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | Foundation for biomedical searching | Full MeSH integration |

| Embase | Drug studies, international coverage | Emtree thesaurus |

| Cochrane Library | Evidence-based medicine resources | MeSH compatible |

| Scopus | Multidisciplinary, citation tracking | Limited vocabulary control |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for MeSH-Based Retrieval

Table 5: MeSH Research Toolkit and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function | Access Point |

|---|---|---|

| MeSH Database | Identify and browse controlled vocabulary | PubMed homepage under "Explore" |

| Yale MeSH Analyzer | Analyze MeSH terms for up to 20 articles | Online tool using PubMed IDs |

| NLM MeSH on Demand | Predict MeSH terms from abstracts/text | NLM web service |

| MeSH Browser | Complete hierarchical browsing | NLM website |

| Automatic Term Mapping | PubMed's query translation system | Built into PubMed search |

MeSH represents an indispensable resource for overcoming the inherent challenges of keyword variability in biomedical literature retrieval. Through its controlled vocabulary and hierarchical structure, MeSH enables researchers to search conceptually rather than lexically, significantly enhancing both recall and precision compared to text-word strategies. The experimental evidence demonstrates clear quantitative advantages: 75% recall for MeSH strategies versus 54% for text-words, with precision advantages of 47.7% versus 34.4% [22]. For drug development professionals and researchers conducting systematic reviews, MeSH provides the methodological foundation for comprehensive, unbiased literature retrieval. The integration of MeSH with supplementary text-words and cross-database searching creates an optimal approach for navigating the increasingly complex landscape of biomedical research, ensuring critical evidence is identified regardless of terminology variations across publications. As biomedical literature continues to expand, mastery of MeSH-based retrieval strategies will remain essential for rigorous scientific investigation and evidence-based decision making.

From Concept to Search Strategy: A Step-by-Step MeSH Methodology

The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus is a controlled and hierarchically-organized vocabulary developed and maintained by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) [2] [19]. Its primary function is to provide uniformity and consistency to the indexing, cataloguing, and searching of biomedical and health-related information within databases like PubMed and MEDLINE [19]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering MeSH is a critical component of effective keyword research, enabling comprehensive literature retrieval that transcends the limitations of natural language.

When an article is indexed for MEDLINE, human indexers or automated systems assign approximately 10-15 MeSH terms to describe its core content [4] [2]. This structured vocabulary solves a fundamental problem in literature search: the variability of author terminology. For instance, a search for the MeSH term "Myocardial Infarction" will automatically retrieve articles that use author keywords like "heart attack" or "acute myocardial injury," ensuring that relevant studies are not missed due to semantic differences [2]. This guide provides a detailed, technical protocol for discovering relevant MeSH terms, forming the essential first step in a robust, evidence-based keyword research strategy.

Comparative Analysis of Search Strategies: MeSH vs. Textwords

A proficient literature search strategy intentionally combines MeSH terms with textwords (also called keywords) to leverage the strengths of both approaches [19]. Textwords are literal terms searched within specific fields like the title and abstract. The table below summarizes the distinct characteristics and applications of each method.

Table 1: Comparison of MeSH Term and Textword Search Strategies

| Feature | MeSH Term Searching | Textword Searching |

|---|---|---|

| Concept Coverage | Searches for a concept's pre-defined synonyms, acronyms, and alternate spellings [19]. | Searches only for the exact terms and their immediate variants used by the author. |

| Search Precision | High precision for retrieving thematically relevant articles, independent of author wording [2]. | Can be lower precision, as terms may appear in contexts different from the intended concept. |

| Ideal Use Case | Retrieving literature on established, well-defined concepts [19]. | Searching for very new ideas, technologies, or concepts not yet represented in MeSH [19]. |

| Indexing Dependency | Only retrieves records that have been fully indexed with MeSH terms [19]. | Retrieves all records, including those too recent to have been assigned MeSH terms [19]. |

The following workflow diagram maps the logical process for discovering and utilizing MeSH terms, integrating with textword searching to ensure a comprehensive search.

Detailed Methodologies for MeSH Term Discovery

Protocol 1: Direct Query of the MeSH Database

This is the primary method for identifying the controlled vocabulary for a given concept.

- Objective: To authoritatively identify and select the most appropriate MeSH term(s) for a research concept.

- Materials and Tools: Internet access and the NLM's MeSH Database, accessible via the PubMed homepage [2].

- Procedure:

- Access: From the PubMed homepage, select "MeSH" from the search box dropdown menu [2].

- Query: Type your research concept (e.g., "diabetes") into the search box. The database will return a list of suggested MeSH terms [19].

- Evaluate: Click on potential MeSH terms to view their full record, which includes:

- Scope Note: A brief definition of the term [19].

- Entry Terms: Synonyms, acronyms, and alternate spellings that map to this MeSH term (e.g., "telemedicine" includes "mobile health," "mhealth," and "ehealth") [19].

- Tree Hierarchy: A visual representation of broader and narrower (child) terms [2] [19].

- Select and Apply: After choosing the appropriate term(s), you can add them to the PubMed search builder. The search will automatically "explode" the term, meaning it includes all more specific terms in the hierarchy [2].

Protocol 2: Reverse-Engineering from a Known Relevant Article

When a concept is new or a direct MeSH query is unsuccessful, analyzing a known relevant article is an effective alternative.

- Objective: To discover relevant MeSH terms by examining the indexed terms of a pivotal article on your topic.

- Materials and Tools: A PubMed record of a known relevant article.

- Procedure:

- Locate: Find a highly relevant article in PubMed.

- Inspect: In the article's abstract view or full record, locate the "MeSH terms" field [2].

- Extract: Identify and note the MeSH terms that describe the core concepts of your research interest. These terms can be directly used or added to the search builder for a new, broader search [2].

Protocol 3: Advanced Trend Analysis Using MeSH Frequency Vectors

For strategic research planning and scientometric analysis, tracking the temporal dynamics of MeSH terms can reveal emerging trends.

- Objective: To identify research topics for which the number of published works has changed significantly over time [4].

- Materials and Tools: A set of PubMed publications (a target group and a control group) and statistical analysis software. The API Scanbious can be used to retrieve PMIDs and associated MeSH terms [4].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Form a target sample of papers (e.g., in personalized medicine) and a background/control sample (e.g., general medicine). For each sample, generate a MeSH-terms's frequency vector, which is the relative frequency of each MeSH term's occurrence normalized to the total number of papers in the sample [4].

- Statistical Comparison: For each term and year, compute the relative frequencies in the target ((PMi/Nt)) and control ((GMi/Nc)) samples. Statistical differences between the frequencies (p-value) can be determined using a proportions test (e.g.,

prop.testin R), with correction for multiple comparisons using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method [4]. - Effect Size Calculation: Calculate a log ratio for each MeSH term using the formula ( \text{logratio} = \log2(PMi/GM_i) ). A positive value indicates the term is more frequent in the target sample. The absolute value indicates the magnitude of the difference [4].

- Trend Analysis: Perform a Mann-Kendall trend test on the frequency of each MeSH term over time (e.g., 2009-2018) to identify terms with consistently increasing or decreasing usage. A p-value ≤ 0.01 is considered indicative of a significant trend [4].

The Researcher's Toolkit for MeSH and Keyword Research

The following table details essential digital tools and resources that facilitate the discovery and application of MeSH terms in scientific keyword research.

Table 2: Essential Digital Tools for MeSH and Keyword Research

| Tool Name | Function | Application in Keyword Research |

|---|---|---|

| NLM MeSH Database | The authoritative source for browsing and searching the entire MeSH thesaurus [2]. | Identifying official terms, definitions, synonyms (Entry Terms), and hierarchical relationships for core concepts. |

| NLM MeSH on Demand | A text analysis tool that predicts MeSH terms based on a submitted abstract or manuscript [19]. | Automatically suggests potential MeSH terms for a specific block of text, aiding in vocabulary discovery. |

| Yale MeSH Analyzer | A utility that groups MeSH headings for up to 20 articles in a table using their PubMed IDs (PMIDs) [19]. | Deconstructing the indexing of multiple key papers to identify recurring and relevant MeSH terms for a search strategy. |

| Automated Term Mapping (ATM) | PubMed's built-in query translation system [15]. | Understanding how untagged search terms are automatically matched to MeSH terms, helping to refine and control searches. |

Updates and Considerations for MeSH in 2025

The MeSH vocabulary is dynamic, with NLM adding, modifying, and occasionally discontinuing terms annually. For 2025, there are 192 new Main Headings [15]. Researchers must be aware of these changes, as they can directly impact search results.

- New Terms: New concepts are continually added. For example,

SCOPING REVIEWis a new Publication Type for 2025, defined as a literature overview that maps available evidence without providing a summary answer, distinct from aSYSTEMATIC REVIEW[15]. Previously, scoping reviews were indexed as "Systematic Review." This change allows for more precise searching, but may alter result counts for existing search filters. - Term Promotions: Entry terms can be promoted to main headings.

AGING IN PLACE, previously an entry term forINDEPENDENT LIVING, is now a main heading itself [15]. A search for the phrase "Aging In Place" will now trigger this new, more specific MeSH term instead of the broader "Independent Living," which may reduce the number of results and increase precision. - Search Strategy Maintenance: Searchers should periodically check their key queries in the MeSH Database to ensure the terms are still current and to identify any new, more specific terms that should be included [15].

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) is the National Library of Medicine's (NLM) controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing, cataloging, and searching biomedical and health-related information [1]. It features a hierarchically-organized structure that provides consistency and precision in retrieving scientific literature. Within this sophisticated system, entry terms serve as critical access points, functioning as synonyms, near-synonyms, and alternate forms of the preferred MeSH terminology [16].

Understanding and leveraging entry terms is fundamental to constructing comprehensive search strategies. These terms account for variations in scientific language, ensuring researchers can locate all relevant literature regardless of the specific terminology used by authors. This guide provides technical methodologies for systematically exploiting entry terms to build robust synonym lists, thereby enhancing recall and precision in biomedical information retrieval.

The Role and Structure of Entry Terms

Definition and Purpose

Entry terms, sometimes called "See cross-references," are synonyms, near-synonyms, alternate forms, and other closely related terms within a MeSH record [16]. While not always strictly synonymous with the preferred descriptor, they are treated as equivalent for the purposes of cataloging, indexing, and retrieval [16]. This functional equivalence makes them invaluable for search strategy development.

The primary purpose of entry terms is to map natural language to controlled vocabulary. When users search with terms they are familiar with, PubMed's Automatic Term Mapping (ATM) mechanism translates these terms to the appropriate MeSH headings via the entry term mapping system [24]. For example, a search for "Heart Arrest" will also retrieve records containing entry terms such as "Arrest, Heart" and "Asystole" [16].

Relationship to Other MeSH Features

Entry terms represent just one type of cross-reference within the MeSH ecosystem. Other important relationships include:

- See Related: Suggests other descriptor records that may be of interest through associative relationships (e.g., "Factor XIII Deficiency see related Factor XIIIa") [16].

- Consider Also: References other descriptors sharing common linguistic roots, primarily used with anatomical terms (e.g., "Brain consider also terms at CEREBR- and ENCEPHAL-") [16].

- MeSH Tree Structures: Display hierarchical relationships that allow for broader and narrower retrieval through parent-child relationships [16].

Unlike these other relationships, entry terms provide direct semantic equivalence, making them uniquely valuable for synonym generation.

Methodological Framework: Extracting and Utilizing Entry Terms

Locating Entry Terms via the MeSH Database

The MeSH Database provides the primary interface for identifying entry terms associated with a specific concept. The following protocol details the systematic extraction of entry terms:

- Access the MeSH Database: Navigate to the MeSH Database via the PubMed homepage (under "More Resources") [25].

- Concept Search: Enter your key search concept into the query box (e.g., "Heart Arrest").

- Review Results: Examine the returned MeSH records and select the most appropriate descriptor.

- Analyze Full Record: Scroll the full descriptor record to locate the "Entry Terms" section, which lists all synonymous terms [25].

- Document Synonyms: Systematically record all entry terms for inclusion in your search strategy.

Table: Entry Term Extraction Workflow

| Step | Action | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Access MeSH Database via PubMed | Interface for controlled vocabulary search |

| 2 | Input conceptual search term | List of potential MeSH descriptors |

| 3 | Select relevant MeSH descriptor | Full MeSH record with complete metadata |

| 4 | Locate "Entry Terms" section | Comprehensive list of synonymous terms |

| 5 | Document all entry terms | Raw materials for synonym list construction |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for extracting and implementing entry terms in a comprehensive search strategy:

Categorizing Entry Terms for Strategic Implementation

Entry terms encompass several distinct types of terminology, each with specific strategic value:

- True Synonyms: Scientifically equivalent terms (e.g., "Asystole" for "Heart Arrest") [16]

- Lexical Variations: Inversions, alternate word orders (e.g., "Arrest, Heart") [16]

- British/American Spellings: Variations in spelling conventions

- Abbreviations/Acronyms: Short forms and initialisms

- Common vs. Technical Terms: Lay language versus scientific terminology

- Historical Terminology: Older terms that may appear in legacy literature

Table: Quantitative MeSH Scope (2025 Data) [15] [26]

| MeSH Component | Total Count | New in 2025 |

|---|---|---|

| Main Headings | 30,956 | 192 |

| Supplementary Concept Records (SCRs) | 323,939 | 1,001 |

| Category G (Phenomena and Processes) | Significant growth | Not specified |

| Category L (Information Science) | Significant growth | Not specified |

Experimental Protocol: Building a Comprehensive Synonym List

Materials and Research Reagents

Table: Essential Research Tools for MeSH Search Strategy Development

| Tool/Resource | Function | Access Point |

|---|---|---|

| MeSH Database | Primary interface for identifying MeSH descriptors and entry terms | PubMed homepage > More Resources > MeSH [25] |

| PubMed Advanced Search | Platform for constructing and executing complex Boolean queries | PubMed homepage > Advanced search [24] |

| MeSH Browser | Displays hierarchical tree structures and relationships | NLM MeSH homepage [1] |

| NLM Technical Bulletin | Provides announcements of MeSH updates and changes | NLM website [15] |

| Automatic Term Mapping (ATM) | PubMed's automatic query translation system | Built into PubMed search algorithm [24] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Phase 1: Conceptual Analysis

- Deconstruct Research Question: Identify core concepts and relationships within your research query.

- List Preliminary Keywords: Brainstorm initial search terms for each concept without consulting controlled vocabulary.

- Identify Potential Ambiguities: Note terms with multiple meanings (e.g., "aids" could refer to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome or assistive devices) [25].

Phase 2: MeSH Database Exploration

- Query Each Concept: Input each preliminary keyword into the MeSH Database.

- Select Appropriate Descriptors: Choose the most relevant MeSH heading for each concept, reviewing scope notes and definitions for accuracy [25].

- Extract Entry Terms: Document all entry terms listed in the full MeSH record.

- Examine Hierarchical Relationships: Review the MeSH tree structure to identify potentially relevant narrower terms [25].

Phase 3: Synonym List Construction

- Compile Entry Terms: Gather all entry terms from relevant MeSH descriptors.

- Supplement with Text Words: Add relevant natural language terms not included as entry terms, including:

- Emerging terminology not yet incorporated into MeSH

- Chemical compounds or gene symbols without dedicated MeSH terms [25]

- Highly specific methodological terms

- Account for Spelling Variations: Include both American and British English spellings.

- Incorporate Abbreviations: Add relevant acronyms and initialisms.

Phase 4: Search Strategy Assembly

- Combine Synonyms with OR: Group all synonymous terms (MeSH headings and text words) for each concept with Boolean OR.

- Apply Search Fields: Tag MeSH terms with

[mesh]and text words with appropriate field tags (e.g.,[tiab]for title/abstract). - Combine Concepts with AND: Link different conceptual groups with Boolean AND.

- Implement Search Limits: Apply methodological filters, date restrictions, or other limits as needed.

Case Study: Myocardial Infarction Search Strategy

To illustrate the practical application of this methodology, consider building a synonym list for "myocardial infarction":

- MeSH Database Query: Searching "myocardial infarction" in the MeSH Database returns the preferred descriptor "Myocardial Infarction" with numerous entry terms including "Heart Attack," "Acute Myocardial Injury," and other variant spellings and plurals [2].

- Entry Term Extraction: The entry terms provide the foundation for the synonym list.

- Synonym List Construction:

- MeSH Terms: "Myocardial Infarction"[mesh]

- Entry Terms: "Heart Attack," "Acute Myocardial Injury," etc.

- Text Words: Additional natural language terms not captured as entry terms

- Search Strategy Assembly:

This approach ensures comprehensive retrieval regardless of the terminology used by authors in their titles or abstracts.

Advanced Technical Applications

Integration with PubMed's Automatic Term Mapping

PubMed's Automatic Term Mapping (ATM) automatically translates search terms to MeSH headings using the entry term mapping system [24]. Understanding this process allows for more sophisticated search strategies:

- Leveraging ATM: Untagged search terms are automatically matched against a translation table that includes MeSH terms and their entry terms [24].

- Bypassing ATM: Using phrase searching (quotation marks) or field tags turns off ATM, requiring explicit synonym management [24].

- Strategic Implications: For comprehensive searching, explicitly including both MeSH terms and text words ensures optimal recall, particularly for newly added terms that may not yet be fully integrated into the translation table.

Managing MeSH Vocabulary Updates

The MeSH vocabulary is updated annually, with new terms added and existing terms modified. These changes directly impact entry terms and search strategies:

- New Descriptors: 192 new main headings were added in the 2025 update [15]. For example, "Aging in Place" was promoted from an entry term of "Independent Living" to a main heading [15] [26].

- Entry Term Promotions: Existing entry terms may be promoted to main headings, changing how searches map to MeSH terms.

- Strategic Adaptation: Regular review of MeSH updates is essential for maintaining search accuracy. The NLM Technical Bulletin provides announcements of these changes [15].

Specialized Search Scenarios

Emerging Concepts and New Terminology

For novel research areas without established MeSH terms, text word searching becomes paramount. However, entry terms of related broader concepts may still provide relevant synonyms. For example, before "Scoping Review" became a publication type in 2025, these articles were indexed under "Systematic Review" [15] [26].

Disambiguation Challenges

Entry terms are particularly valuable for distinguishing between homonyms. For example, searching "aids" without controlled vocabulary retrieves articles on both Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and hearing aids [25]. Using the MeSH term "Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome" with its entry terms ensures precise retrieval.

Validation and Optimization Techniques

Recall and Precision Assessment

- Benchmark Testing: Identify key known articles relevant to your research topic and verify they are retrieved by your search strategy.

- Recall Validation: Check if searches using author names or specific title words are captured by your synonym-based strategy.

- Precision Sampling: Randomly sample retrieved results to assess relevance and adjust term inclusion accordingly.

Search Strategy Refinement

- Term Frequency Analysis: Use PubMed's search results to identify frequently occurring terms in relevant articles.

- MeSH Term Explosion Management: By default, PubMed includes more specific terms in a hierarchy (automatic "explode"). This can be disabled with

[mesh:noexp]for greater precision [24]. - Major Topic Restriction: Restricting to MeSH Major Topic (

[majr]) retrieves articles where the subject is a primary focus, improving precision [25].

Documentation and reproducibility

Maintain detailed records of:

- MeSH descriptors utilized

- All entry terms incorporated

- Text words added

- Date of search execution

- Database version (MeSH year)

- Result counts for each iteration

This documentation ensures reproducibility and facilitates strategy updating as MeSH evolves.

Systematic leveraging of MeSH entry terms provides a methodological foundation for comprehensive synonym list construction in biomedical literature searching. By following the protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can develop search strategies that account for terminology variation while maintaining precision. The dynamic nature of the MeSH vocabulary necessitates ongoing attention to updates and modifications, particularly the annual changes that introduce new descriptors and modify existing entry terms. When integrated with text word searching and other advanced PubMed features, entry term analysis forms an essential component of robust, reproducible search methodologies for evidence synthesis and scientific discovery.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) represent a critical controlled vocabulary thesaurus produced by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) for the consistent indexing, cataloging, and searching of biomedical and health-related information [1]. Within this hierarchically-organized system, MeSH subheadings (also known as qualifiers) serve as powerful tools that enable researchers to focus their searches on specific aspects or facets of a main subject heading. By attaching a subheading to a main MeSH term, searchers can precisely narrow the scope of their query to target particular research methodologies, anatomical locations, or conceptual themes within a broader topic area. This practice is indispensable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require high-precision retrieval from vast biomedical databases like MEDLINE/PubMed, particularly when conducting systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or comprehensive landscape analyses of emerging research fields [27] [28].

The strategic application of subheadings transforms generic subject searches into targeted investigations of specific relationships, interventions, or processes. For example, while the MeSH heading "Atrial Fibrillation" alone might retrieve thousands of articles, adding the subheading "/drug therapy" specifically limits results to publications addressing pharmaceutical interventions for this condition [20]. This precision is especially valuable in drug development research, where distinguishing between pharmacological actions, therapeutic uses, adverse effects, and analytical methodologies is essential for efficient knowledge discovery. Proper subheading usage directly addresses the challenges posed by the exponential growth of biomedical literature by filtering out irrelevant results and concentrating on the specific aspect of interest [27].

Table 1: Categories of MeSH Subheadings and Their Research Applications

| Category | Subheading Examples | Primary Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic | /drug therapy, /therapeutic use, /surgery | Investigating treatment modalities and clinical interventions |

| Etiologic | /chemically induced, /etiology, /genetics | Understanding disease causes and risk factors |

| Methodological | /analysis, /diagnosis, /methods | Developing and validating research techniques and tools |

| Physiological | /metabolism, /pharmacokinetics, /physiology | Studying biological processes and mechanisms |

| Descriptive | /classification, /education, /history | Contextualizing knowledge and educational applications |

The Structure and Function of Subheadings

Conceptual Framework of Subheading Organization

MeSH subheadings operate within a carefully structured conceptual framework designed to accommodate the multidimensional nature of biomedical research. The current MeSH thesaurus includes approximately 83 subheadings that can be combined with main headings in semantically meaningful ways, though not all combinations are permitted due to logical constraints [29] [20]. This combinatorial system follows explicit rules where each subheading is specifically designed to qualify particular categories of main headings. For instance, the subheading "/blood" can be attached to terms representing diseases (e.g., "Hypertension/blood") to retrieve articles about blood levels of substances in relation to that disease, or with drug terms (e.g., "Aspirin/blood") to find literature on the pharmacokinetics and concentration monitoring of pharmaceuticals.

The intellectual foundation of this system recognizes that biomedical knowledge exists along multiple axes: anatomical (where), methodological (how), conceptual (what), and temporal (when). Subheadings provide the semantic bridges that connect these dimensions in retrievable ways. The NLM's indexing manual establishes precise guidelines for human indexers regarding which subheading-main heading combinations are valid, ensuring consistency across the MEDLINE database [20]. This systematic approach to knowledge organization directly supports the information retrieval needs of drug development professionals who must navigate complex interdisciplinary relationships between chemical compounds, biological targets, disease processes, and research methodologies.

Subheading-Topic Relationship Mapping

The directed graph above illustrates the fundamental relationship between a MeSH main heading and its applicable subheadings. This logical structure demonstrates how a broad subject heading branches into increasingly specific conceptual facets, enabling precision in information retrieval. The subheading application process follows predetermined compatibility rules maintained by the NLM, which ensures consistent indexing and reliable searching across the biomedical literature [20].

Methodology for Subheading Application

Experimental Protocol for Subheading Identification and Implementation

Objective: To systematically identify and apply relevant MeSH subheadings to focus a literature search on specific aspects of a research topic in PubMed/MEDLINE.

Materials and Equipment:

- Computer with internet access

- PubMed database interface (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)

- MeSH Browser (https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/)

- Search strategy documentation tool (e.g., spreadsheet or electronic lab notebook)

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for MeSH Search Optimization

| Reagent/Resource | Manufacturer/Provider | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| MeSH Browser | National Library of Medicine | Browse and identify appropriate MeSH terms and subheadings |

| PubMed Database | NCBI/NLM | Execute subheading-qualified searches against MEDLINE |

| Search Strategy Template | Researcher-developed | Document search methodology for reproducibility |

| Citation Management Software | Various (EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley) | Manage and deduplicate retrieved references |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Initial Topic Deconstruction: Break down your research question into core conceptual components. For a sample query on "pharmacist interventions in medication adherence for hypertension," identify key concepts: "pharmacists," "medication adherence," and "hypertension" [20].

MeSH Heading Identification: For each core concept, identify the most specific appropriate MeSH heading using the MeSH Browser at https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/ [29].

- Navigate to the MeSH Browser interface

- Enter potential term candidates into the search box

- Select "Main Heading (Descriptor) Terms" from the "Search in field" dropdown

- Execute search and review results for precise terminology

- Verify hierarchical positioning within the MeSH tree structure

Subheading Compatibility Assessment: For each identified main heading, determine which subheadings are applicable and logically compatible.

- Within the MeSH Browser record for each heading, review the "Allowable Qualifiers" section

- Note which subheadings are designated as frequently used ("FX") for efficient indexing

- Consider which subheading best represents the aspect of your research focus

Search Syntax Construction: Implement subheadings in PubMed using standard syntax conventions.

- Use the bracket syntax: "Hypertension/drug therapy"[Mesh]

- Alternatively, use the colon syntax: "Hypertension/therapy"[Mesh]

- For multiple subheadings, apply separately: "Pharmacists"[Mesh] AND "Medication Adherence"[Mesh] AND "Hypertension/drug therapy"[Mesh]

Search Execution and Results Validation: Execute the constructed search and validate results for relevance.

- Review first 20-30 results for topical relevance to research question

- If precision is too low, consider adding additional subheading qualifications

- If recall is too low, consider removing less critical subheading restrictions

- Iteratively refine search strategy based on results assessment

Search Strategy Documentation: Comprehensively document the final search strategy including all MeSH headings, subheadings, Boolean operators, and field tags for reproducibility and peer review.

Workflow for Systematic Search Using MeSH Subheadings

The workflow diagram above outlines the systematic process for applying MeSH subheadings to focus a literature search. This methodology emphasizes the iterative nature of search development, where results evaluation informs subsequent refinement of the search strategy. The process aligns with established practices for systematic searching while incorporating the specific technical requirements of the MeSH vocabulary system [20].

Analytical Framework for Subheading Utilization

Quantitative Analysis of Subheading Application Patterns

The application of MeSH subheadings follows discernible patterns across different biomedical research domains. A meta-research study examining the use of 'Pharmaceutical Services' MeSH terms revealed significant insights about subheading utilization in specialized literature. The analysis of 2012 primary articles included in 138 meta-analyses on pharmacists' interventions demonstrated that only 36.6% of studies were indexed with at least one MeSH term from the 'Pharmaceutical Services' branch, and in fewer than 20% of cases were these terms designated as 'Major MeSH' [28]. This indicates substantial underutilization of available subheadings in specialized domains, which has direct implications for search recall and precision.