Hormonal Dynamics Across Menstrual Cycle Patterns: From Foundational Biology to Clinical and Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the hormonal trends underlying diverse menstrual cycle patterns, synthesizing foundational endocrinology with contemporary large-scale data analytics.

Hormonal Dynamics Across Menstrual Cycle Patterns: From Foundational Biology to Clinical and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the hormonal trends underlying diverse menstrual cycle patterns, synthesizing foundational endocrinology with contemporary large-scale data analytics. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the physiological basis of cycle variability, innovative methodologies for cycle phase detection, the impact of demographic factors like age and BMI on cycle characteristics, and the implications for validating therapeutic interventions. The synthesis aims to bridge the gap between basic science, real-world evidence, and the development of personalized hormone therapies and diagnostic tools.

The Endocrine Architecture of the Menstrual Cycle: Defining Normal and Variable Patterns

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian (HPO) Axis and Phase Regulation

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian (HPO) axis represents the primary regulatory system controlling the female reproductive cycle, orchestrating a complex series of hormonal events that occur in a precise, cyclical pattern. This sophisticated neuroendocrine axis integrates signals from the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries to regulate menstrual cycle physiology through intricate feedback mechanisms. Understanding the phase regulation of the HPO axis is fundamental to reproductive endocrinology, providing critical insights for developing therapeutic interventions for ovulatory disorders, which account for approximately 25% of infertility diagnoses [1]. This guide objectively compares hormonal trends and experimental data across different menstrual cycle patterns, providing researchers and drug development professionals with methodological frameworks for investigating this essential physiological system.

HPO Axis Regulatory Mechanics and Phase Characteristics

Core Components and Signaling

The HPO axis functions as a synchronized communication network between the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary gland, and ovaries, regulating reproductive hormones through bidirectional signaling [1]. The hypothalamic unit contains specialized Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) neurons that originate in the embryonic olfactory placode and migrate to the arcuate nucleus during fetal development [2]. These neurons release GnRH in pulsatile patterns approximately every hour when devoid of feedback influences, with this pulsatile release being absolutely essential for normal gonadotropin secretion [2]. The anterior pituitary gonadotropes respond to these GnRH pulses by synthesizing and releasing the gonadotropins Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), which then act on ovarian receptors to stimulate folliculogenesis and steroid hormone production [2].

Menstrual Cycle Phase Regulation

The menstrual cycle is systematically divided into two primary phases—the follicular and luteal phases—separated by ovulation and ending with either fertilization or menstruation [3]. The follicular phase begins with menses and involves follicular recruitment, selection, and maturation under rising FSH influence, culminating in rising estradiol levels [2] [4]. The luteal phase begins after ovulation when the ruptured follicle transforms into the corpus luteum, secreting progesterone and estradiol in a characteristic bell-shaped pattern that lasts 13-15 days unless pregnancy occurs [2] [5].

The following table summarizes the key hormonal characteristics and regulatory mechanisms across menstrual cycle phases:

Table 1: Hormonal Regulation and Characteristics Across Menstrual Cycle Phases

| Cycle Phase | Duration | Dominant Hormones | Key Regulatory Mechanisms | Primary Ovarian Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follicular Phase | ~14 days (variable) | Low-to-rising estradiol, moderate FSH | Negative feedback of low estrogen on FSH/LH; switch to positive feedback near end | Follicular recruitment, selection, and maturation of dominant follicle |

| Ovulation | ~24 hours | Peak LH surge, high estradiol | Sustained high estradiol triggers positive feedback and GnRH surge | Rupture of mature follicle and oocyte release |

| Luteal Phase | 13-15 days (fixed) | High progesterone, moderate estradiol | Negative feedback of progesterone and estrogen on FSH/LH | Corpus luteum formation and secretory activity; regression if no pregnancy |

Feedback Control Systems

The HPO axis employs sophisticated feedback mechanisms that switch between negative and positive regulation to control cycle progression. During most of the cycle, moderate estrogen levels exert negative feedback on GnRH and gonadotropin secretion [4]. However, in a critical regulatory shift, high estrogen levels in the late follicular phase (in the absence of progesterone) initiate positive feedback on the HPG axis, resulting in the preovulatory GnRH and LH surges necessary for ovulation [4] [5]. The mechanisms enabling this switch are not fully understood but involve increased GnRH receptor expression and enhanced gonadotrope sensitivity [5]. Following ovulation, progesterone dominates and, in the presence of estrogen, re-establishes negative feedback throughout the luteal phase [4].

Experimental Methodologies for HPO Axis Investigation

Hormonal Assessment Protocols

Longitudinal hormonal monitoring across the menstrual cycle requires precise methodological approaches. The GnRH stimulation test represents a conventional diagnostic protocol that involves an initial baseline blood draw, intravenous administration of GnRH, followed by multiple blood samples collected over two hours, with a final sample taken 24 hours post-administration [1]. This test assesses FSH, LH, and sex hormone dynamics to evaluate GnRH function and pituitary responsiveness. For comprehensive hormonal mapping, the DUTCH Cycle Mapping Plus protocol utilizes dry urine samples collected throughout the menstrual cycle to assess sex hormone variability and cortisol patterns, providing a non-invasive method for evaluating HPO axis function [1].

Cycle Phase Determination Methods

Accurate menstrual cycle phase determination is essential for valid HPO axis research. The following table compares common methodological approaches for cycle phase assessment:

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Menstrual Cycle Phase Determination

| Method Type | Specific Techniques | Key Measured Parameters | Accuracy Considerations | Practical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counting Methods | Forward counting from menstruation; backward counting from next menses | Cycle day assignment based on start date of bleeding | Limited accuracy; assumes standardized cycle length | Initial screening; large epidemiological studies |

| Ovulation Detection | Urinary LH surge detection; basal body temperature (BBT) tracking | LH peak identification; BBT biphasic pattern confirmation | High accuracy for ovulation timing; BBT confirms ovulation after occurrence | Fertility monitoring; phase-specific interventions |

| Hormonal Verification | Serum progesterone (>3 ng/mL indicates ovulation); estradiol levels | Direct measurement of steroid hormones from blood samples | Highest accuracy; resource-intensive | Clinical trials; precise endocrine profiling |

The most rigorous research protocols implement LH peak detection or serum progesterone measurement to definitively confirm ovulation and phase assignment, as counting methods alone frequently misclassify cycle phases [6]. For determining ovulatory cycles via BBT, researchers typically define a biphasic pattern as a difference greater than 0.3°C between the mean luteal phase temperature (10 days preceding next menstruation) and follicular phase temperature (first 10 days from cycle start) [7].

Advanced Assessment Techniques

Functional medicine laboratories often incorporate Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) testing to assess ovarian reserve and follicular status, with particularly high levels indicating conditions like Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) [1]. Complete thyroid panels including thyroid antibodies help evaluate thyroid involvement in HPO axis dysfunction, as both primary hypothyroidism and autoimmune thyroiditis can disrupt ovulatory function [1]. For structural assessment, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify intracranial tumors, pituitary abnormalities, or other anatomical variants that may disrupt HPO axis signaling at the hypothalamic or pituitary level [1].

Quantitative Hormonal Trends and Dysregulation Patterns

Normative Hormonal Fluctuations

In normally cycling women, characteristic hormonal patterns emerge across phases. FSH demonstrates a small but significant rise at the end of the preceding menstrual cycle, initiating recruitment of secondary early antral follicles [2]. Estradiol levels rise progressively during follicular development, reaching peak concentrations (approximately 200-400 pg/mL) just before ovulation when the dominant follicle achieves maturation [2]. The LH surge rises dramatically (near-tripling baseline levels) to trigger ovulation, while progesterone remains low during the follicular phase but rises sharply after ovulation to peak levels approximately 7 days post-ovulation [2] [5].

Body Mass Index (BMI) Influence on Cycle Characteristics

Recent large-scale research utilizing smartphone application data from 8,745 participants with 191,426 menstrual cycles has quantified the nonlinear relationship between BMI and menstrual cycle regularity [7]. The findings demonstrate that individuals with a BMI of 20 kg/m² showed optimal cycle characteristics, with both lower and higher BMI values associated with progressively greater cycle irregularities:

Table 3: BMI Impact on Menstrual Cycle Parameters (Adapted from Itoi et al., 2025)

| BMI Category | Cycle Length Change vs. BMI 20 | Infrequent Menstrual Bleeding Risk (OR) | Absent Menstrual Bleeding Risk (OR) | Biphasic Cycle Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight (≤16 kg/m²) | +1.03 days | Significantly higher | 1.78 | Decreased |

| Normal (18.5-22.9 kg/m²) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Optimal |

| Overweight (23-24.9 kg/m²) | Minimal change | 1.56 | Not significant | Slightly decreased |

| Obese (25-35 kg/m²) | +1.06 days | 2.63 | 1.94 | Significantly decreased |

This research established an inverted J-shaped relationship between BMI and the proportion of biphasic cycles, confirming that both low and high BMI increase the risk of anovulatory cycles and potential ovulatory infertility [7]. The data specifically indicated that AMB risk became significantly higher at BMI values ≤19 kg/m² or ≥26 kg/m² compared to the optimal BMI of 20 kg/m² [7].

HPO Axis Dysfunction Classification

The World Health Organization categorizes ovulatory disorders resulting from HPO axis dysfunction into three distinct groups [1]. Group 1 (Hypothalamic Pituitary Failure) involves disrupted communication between the hypothalamus and pituitary leading to absent GnRH release, with conditions including idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, Kallmann Syndrome, and intracranial tumors [1]. Group 2 (Eugonadal Ovulatory Dysfunction) represents a broad spectrum where HPO compromise occurs despite normal gonadal function, encompassing PCOS, obesity, hyperprolactinemia, and primary hypothyroidism [1]. Group 3 (Primary Ovarian Insufficiency) occurs when primary dysfunction originates in the ovaries themselves due to genetic factors (Turner Syndrome), autoimmune conditions, environmental toxins, or cancer treatments [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HPO Axis Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Specific Application | Research Function | Example Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| GnRH Analogues | GnRH stimulation tests; pulsatility studies | Assess pituitary responsiveness; investigate pulse generator function | Diagnostic testing for hypothalamic amenorrhea |

| LH/FSH Immunoassays | Serum and urine hormone measurement | Quantify gonadotropin levels across cycle phases | LH surge detection; follicular phase FSH assessment |

| Steroid Hormone ELISA Kits | Estradiol, progesterone measurement | Monitor ovarian steroidogenesis output | Luteal phase adequacy assessment; follicular development |

| AMH Detection Kits | Ovarian reserve testing | Evaluate follicular pool and recruitment | PCOS diagnosis; fertility assessment |

| RNA In Situ Hybridization Probes | Kisspeptin and GnRH neuron studies | Investigate neuronal regulation of HPO axis | Neuroendocrine mechanism research |

| BBT Tracking Devices | Ovulation confirmation | Detect post-ovulatory temperature rise | Fertility monitoring; cycle phase verification |

| MRI Contrast Agents | Hypothalamic-pituitary imaging | Visualize structural abnormalities | Tumor identification; anatomical assessment |

Integrated Data Interpretation and Research Implications

The investigation of HPO axis phase regulation reveals complex interactions between neurological, endocrine, and metabolic systems. Research consistently demonstrates that optimal BMI maintenance (approximately 20 kg/m²) supports regular ovulatory function, while deviations in either direction disrupt cycle regularity and ovulation rates [7]. The two-cell theory of estrogen production provides a fundamental framework for understanding ovarian steroidogenesis, where theca cells (under LH stimulation) produce androgens that granulosa cells (under FSH influence) convert to estrogens through aromatase activity [5]. This cooperative process ensures appropriate estrogen levels for both negative and positive feedback effects on the central components of the HPO axis.

Emerging research has also elucidated interactions between the HPO axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, with a recent meta-analysis of 121 longitudinal studies demonstrating higher cortisol concentrations in the follicular phase compared to the luteal phase (dSMC = 0.12, p = .004) [8] [6]. This cross-system interaction may explain how psychological and physical stressors can disrupt menstrual cyclicity through HPA-mediated effects on GnRH pulsatility. Additionally, the discovery of kisspeptin signaling has advanced understanding of how metabolic and environmental inputs regulate the GnRH pulse generator, with kisspeptin neurons acting as intermediaries in transmitting sex steroid feedback to GnRH neurons [2].

For researchers investigating HPO axis function, incorporating multiple assessment methodologies strengthens experimental validity. Combining temporal hormone mapping with functional status biomarkers and structural imaging when indicated provides a comprehensive approach to characterizing HPO axis phase regulation across normal and pathological states. These integrated approaches facilitate the development of targeted interventions for ovulatory disorders and reproductive conditions affecting this essential regulatory system.

HPO Axis Regulatory Signaling and Feedback Pathways

Methodological Approaches for HPO Axis Investigation

The menstrual cycle is a quintessential physiological rhythm governed by precise fluctuations in key reproductive hormones. For researchers and drug development professionals, quantifying the production rates of estrogen and progesterone across the follicular, ovulatory, and luteal phases provides critical insights into female reproductive health and endocrine pathophysiology [9] [10]. These hormonal dynamics not only regulate ovulation and endometrial preparation but exert systemic influences on metabolism, cardiovascular function, and neural connectivity [10] [11] [12].

Advanced metabolomic studies reveal that of 397 metabolites tested, 208 show significant changes throughout the menstrual cycle, with rhythmic patterns observed in neurotransmitter precursors, glutathione metabolism, and urea cycle components [10]. This biochemical rhythmicity underscores the far-reaching impact of estrogen and progesterone fluctuations beyond reproductive tissues. Furthermore, emerging digital health technologies now enable correlation of hormonal status with real-time physiological biomarkers, offering new paradigms for monitoring endocrine function [11].

This comparison guide synthesizes current experimental data on hormonal production rates, detailing the methodologies enabling precise quantification and presenting standardized reference values for research applications. We focus specifically on the comparative dynamics of estrogen and progesterone across distinct menstrual phases, providing a foundation for diagnostic development and therapeutic innovation.

Hormonal Dynamics Across Menstrual Phases

Phase-Specific Hormonal Patterns

The menstrual cycle comprises three principal phases characterized by distinct endocrine milieus. The follicular phase begins with menstruation, marked by low estrogen and progesterone levels, followed by gradual estrogen elevation driven by developing ovarian follicles [9] [13]. The ovulatory phase features a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), triggering ovulation approximately 16-32 hours post-LH peak [9] [14]. The luteal phase follows ovulation, characterized by progesterone dominance from the corpus luteum, with elevated estrogen levels during most of this phase [9].

Table 1: Hormonal Concentration Ranges Across Menstrual Cycle Phases

| Hormone | Follicular Phase | Ovulatory Phase | Luteal Phase | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | 20-400 pg/mL [13] | 150-750 pg/mL [13] | 30-450 pg/mL [13] | LC-MS, Immunoassay |

| Progesterone | <1 ng/mL | 5-20 ng/mL [13] | Serum immunoassay | |

| LH | 0.61-16.3 IU/mL (midcycle peak) [13] | Immunoassay | ||

| FSH | 5-20 mIU/mL [13] | Immunoassay |

Recent research utilizing wearable technology has quantified the physiological impact of these hormonal fluctuations. A groundbreaking study analyzing over 45,000 cycles demonstrated that resting heart rate increases by an average of 2.73 BPM from the follicular to luteal phase, while heart rate variability decreases by 4.65 ms, reflecting the measurable cardiovascular influence of hormonal changes [11].

Comprehensive Hormonal Fluctuations

The endocrine orchestration of the menstrual cycle involves complex feedback systems between the hypothalamus, pituitary, and ovaries. The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis regulates this process through both negative and positive feedback mechanisms [9] [15]. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus stimulates pituitary release of FSH and LH, which in turn modulate ovarian production of estrogen and progesterone [15].

Table 2: Hormonal Reference Values for Cycle Phase Classification in Research Settings

| Cycle Phase | Estradiol (pg/mL) | Progesterone (ng/mL) | LH (IU/mL) | FSH (IU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Follicular | 20-400 [13] | <1 | Low | 5-20 [13] |

| Late Follicular | Rising | <1 | Rising | Variable |

| Ovulatory | 150-750 [13] | Initial rise | 0.61-16.3 [13] | Surge |

| Luteal | 30-450 [13] | 5-20 [13] | Low | Low |

Metabolomic analyses further reveal that these hormonal shifts associate with significant systemic changes. During the luteal phase, 39 amino acids and derivatives and 18 lipid species demonstrate decreased concentrations, potentially indicating an anabolic state during the progesterone peak with recovery during menstruation and follicular phase [10]. These findings highlight the extensive metabolic impact of menstrual cycle hormonal fluctuations.

Experimental Quantification Methodologies

Analytical Techniques for Hormone Assessment

Accurate quantification of estrogen and progesterone across menstrual phases relies on sophisticated analytical platforms, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The following experimental protocols represent current best practices for hormonal assessment in research settings.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

- Application: Comprehensive metabolomic profiling of steroid hormones and their metabolites [10]

- Protocol: Plasma and urine samples are collected at specific cycle phases (menstrual, follicular, periovular, luteal, premenstrual). Samples undergo protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, and derivatization before analysis. Chromatographic separation precedes mass spectrometric detection with selective ion monitoring [10]

- Sensitivity: Capable of detecting hormone concentrations in picogram per milliliter range

- Advantages: High specificity, ability to measure multiple analytes simultaneously, distinction between structurally similar hormones

Immunoassays

- Application: Clinical measurement of estradiol, progesterone, LH, and FSH [13]

- Protocol: Serum samples collected during specific cycle phases (e.g., days 2-3 for FSH/estradiol; days 19-22 for progesterone). Competitive binding assays using antibody-antigen reactions with enzymatic, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent detection [13]

- Platforms: Includes tests from Access Medical Laboratories, ZRT Laboratories, and Boston Heart Diagnostics

- Considerations: Antibody specificity challenges with structurally similar steroids; more cost-effective than MS

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection (HPLC-FLD)

- Application: Quantification of B vitamins and cofactors that interact with hormonal pathways [10]

- Protocol: Serum or plasma samples undergo deproteinization, followed by chromatographic separation with fluorescence detection for specific analytes like riboflavin

- Utility: Assessment of micronutrient status relevant to hormone metabolism

DUTCH Complete Testing (Dried Urine Test for Comprehensive Hormones)

- Application: Comprehensive hormone metabolite profiling [13]

- Protocol: Urine collection during luteal phase with analysis of estrogen, progesterone, androgen metabolites, cortisol patterns, and organic acids via LC-MS/MS

- Advantage: Non-invasive collection with insights into hormone metabolism pathways and clearance

Flow Cytometric Receptor Quantification

- Application: Measurement of estrogen and progesterone receptors at cellular level [16]

- Protocol: Cell lines or clinical samples stained with fluorescent-labeled monoclonal antibodies against ERα and PgR. Quantification using Molecules of Equivalent Soluble Fluorochrome (MESF) units via flow cytometry [16]

- Advantage: Not affected by endogenous steroid competition, single-cell resolution

Phase Classification in Research Protocols

Standardized phase classification is essential for reproducible hormonal research. The following criteria, adapted from large-scale metabolomic studies, enable precise phase determination [10]:

- Menstrual Phase (Days 1-5): Characterized by low estradiol and progesterone, with menstrual bleeding

- Follicular Phase (Days 1-13): Rising estradiol levels, with FSH initially elevated then decreasing as dominant follicle emerges

- Periovulatory Phase: Detected via urinary LH surge testing or serum LH elevation, occurring 16-32 hours before ovulation

- Luteal Phase (Days 15-28): Elevated progesterone with moderate estrogen levels, further subdivided into early, mid, and late luteal

- Premenstrual Phase: Declining progesterone and estrogen preceding menstruation

For increased precision, some research protocols implement the "5-phase cycle classification" incorporating serum hormones, urinary LH, and self-reported cycle timing [10]. Dense sampling protocols with collections every 1-2 days throughout the cycle (as in DUTCH Cycle Mapping) provide the highest temporal resolution for capturing hormonal dynamics [13].

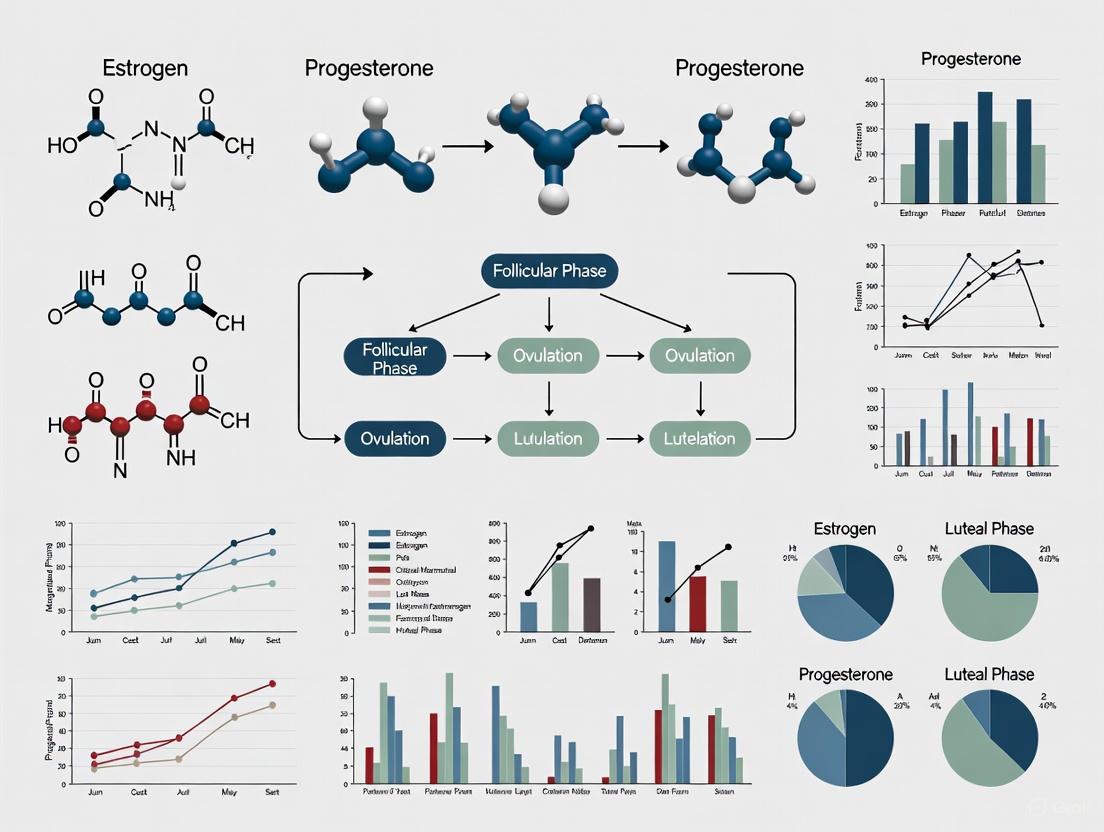

Signaling Pathways and Hormonal Regulation

The endocrine orchestration of the menstrual cycle involves complex interactions between hypothalamic, pituitary, and ovarian hormones. The following diagram illustrates the key regulatory pathways and feedback mechanisms.

This hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis demonstrates the complex regulatory network governing menstrual cycle hormonal production. Note the dual positive and negative feedback mechanisms of estradiol, which transition according to concentration and duration of exposure [9] [15]. The positive feedback loop at high mid-cycle estradiol levels triggers the LH surge essential for ovulation, while progesterone maintains consistent negative feedback throughout the luteal phase [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hormonal Quantification

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Standards | Deuterated estradiol (estradiol-d4), Progesterone-d9 | LC-MS/MS quantification | Isotope-labeled internal standards for precise quantification |

| Immunoassay Kits | Access FSH, Estradiol, LH, Progesterone assays (Roche); ZRT Salivary Hormone Kits | Clinical hormone measurement | Antibody-based detection with enzymatic or chemiluminescent signal |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | ERα (clone ID5), PgR (clone PR-2C5) | Flow cytometric receptor quantification [16] | Specific epitope recognition, fluorescent conjugation capability |

| Sample Preparation | Solid-phase extraction cartridges (C18), Protein precipitation reagents (methanol, acetonitrile) | Sample clean-up prior to analysis | Efficient hormone extraction, matrix interference removal |

| Quality Controls | Bio-Rad Liquichek Unassayed Chemistry Controls; UTAK steroid controls | Method validation | Known concentration materials for assay precision and accuracy |

| Cell Culture Models | MCF-7 breast cancer cells, T47D cells | Receptor binding studies [16] | Endogenous hormone receptor expression, responsive to hormonal manipulation |

| Calibration Materials | MESF (Molecules of Equivalent Soluble Fluorochrome) beads [16] | Flow cytometry standardization | Quantitative fluorescence reference for cellular receptor count |

Comparative Data Synthesis

The quantitative profiles of estrogen and progesterone across menstrual phases demonstrate predictable yet variable patterns essential for understanding female endocrine physiology. Estradiol shows the greatest dynamic range, increasing approximately 20-fold from early follicular to ovulatory phases, while progesterone exhibits the most dramatic phase-dependent shift, rising from negligible follicular levels to dominant luteal concentrations [9] [13].

These hormonal fluctuations correlate with measurable physiological changes beyond the reproductive system. Recent research utilizing wearable technology has established that cardiovascular metrics follow consistent patterns throughout the menstrual cycle, with resting heart rate lowest during menstruation and peaking in the luteal phase, while heart rate variability shows the opposite pattern [11]. The magnitude of these cardiovascular changes, quantified as "Cardiovascular Amplitude," may provide a novel digital biomarker for hormonal status and cycle regularity [11].

Metabolomic studies further reveal that the luteal phase is associated with decreased levels of 39 amino acids and derivatives and 18 lipid species, potentially indicating an anabolic state during the progesterone peak [10]. This systematic metabolic rhythmicity underscores the far-reaching impact of menstrual cycle hormones and offers potential diagnostic applications for hormone-related disorders.

For researchers investigating hormonal contraceptives, comparative studies reveal that combined oral contraceptives (OCs) create a hypogonadal state characterized by suppressed endogenous hormone production, with synthetic hormones potentially mimicking hyperprogestogenic brain states despite overall endocrine suppression [12]. This paradoxical effect highlights the complexity of endocrine disruption and replacement strategies.

Standardized hormonal quantification across menstrual phases provides essential reference data for developing targeted interventions for ovulatory disorders, luteal phase defects, and hormone-sensitive conditions. The experimental methodologies detailed herein enable precise characterization of these endocrine patterns for both research and clinical applications.

Menstrual cycle variability is a critical factor in women's health, influencing everything from fertility to metabolic health. While total cycle length is the most commonly tracked metric, a growing body of evidence demonstrates that this variability stems predominantly from differences in the follicular phase duration. This phase, encompassing the time from menstruation onset to ovulation, exhibits substantially greater fluctuation than the subsequent luteal phase. Understanding this dynamic is essential for researchers studying reproductive endocrinology, drug development professionals designing hormone-based therapies, and clinicians interpreting cycle data in both research and clinical settings. This analysis examines the quantitative evidence supporting follicular phase variability and the experimental methodologies enabling these insights, providing a foundation for comparative studies of hormone trends across different menstrual cycle patterns.

Quantitative Evidence of Phase Variability

Multiple large-scale studies provide compelling quantitative evidence that follicular phase length is the principal contributor to menstrual cycle variability, while the luteal phase remains relatively stable.

Table 1: Comparative Phase Length Variability Across Key Studies

| Study & Population | Cycle Length (Days) | Follicular Phase Length (Days) | Luteal Phase Length (Days) | Key Findings on Variability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bull et al. (2019) [17]: 124,648 women, 612,613 cycles | 29.3 (mean) | 16.9 (95% CI: 10-30) | 12.4 (95% CI: 7-17) | Follicular phase contributed most to cycle length variation; luteal phase more stable |

| Fehring et al. (2006) [18]: 141 women, 1,060 cycles | 28.9 (SD = 3.4) | Not specified | Not specified | 42.5% of women showed intracycle variability >7 days; follicular phase contributed most to this variability |

| Prior et al. (2024) [19]: 53 women, 676 ovulatory cycles | Variance: 10.3 days | Variance: 11.2 days | Variance: 4.3 days | Within-woman follicular phase variances significantly greater than luteal phase variances (P < 0.001) |

The data consistently demonstrate that the standard deviation and variance of follicular phase length substantially exceed those of the luteal phase across diverse populations. The luteal phase typically maintains a more consistent duration of approximately 12-14 days in normally ovulatory cycles, while follicular phase length can vary considerably between women and even within the same woman across consecutive cycles [20] [17].

Experimental Protocols for Phase Determination

Research characterizing menstrual cycle variability relies on precise methodologies for determining ovulation, which demarcates the follicular and luteal phases. The following experimental approaches represent gold standards in the field.

Hormonal Assay Protocol (North Carolina Early Pregnancy Study)

The North Carolina Early Pregnancy Study employed rigorous hormonal monitoring to precisely identify ovulation timing [21]:

- Daily Urine Collection: Participants collected first-morning urine specimens throughout their menstrual cycles, providing a consistent biological matrix for hormone measurement.

- Hormone Metabolite Analysis: Specimens were assayed for estrone-3-glucuronide (E1-3G), a metabolite of estrogen, and pregnanediol-3-glucuronide (Pd-3G), a metabolite of progesterone, using immunoassay techniques.

- Ovulation Estimation: The day of ovulation was estimated using a validated algorithm based on the ratio of Pd-3G to E1-3G, which identifies the initial rise in progesterone metabolites following ovulation.

- Cycle Phase Calculation: Follicular phase length was calculated as the number of days from the first day of menses up to (but not including) the estimated day of ovulation.

This protocol allowed researchers to precisely quantify follicular phase length and examine factors influencing its variability, including marijuana use, oral contraceptive history, and reproductive history [21].

Basal Body Temperature (BBT) Methodology

The prospective 1-year study by Prior et al. utilized basal body temperature tracking to determine ovulatory timing [19]:

- Daily Temperature Measurement: Participants recorded first morning oral temperature immediately upon waking, before any physical activity.

- Quantitative BBT Analysis (QBT): Researchers applied a validated least-squares quantitative basal temperature algorithm to identify the biphasic pattern characteristic of ovulation.

- Phase Determination: The day of ovulation was identified as the day before the sustained BBT rise, with follicular phase length calculated from menses onset to this point.

- Quality Control: Cycles with temperature data for fewer than 50% of days were excluded from analysis to ensure reliability.

This methodology enabled the collection of extensive longitudinal data (694 cycles) with confirmation of ovulation, providing robust evidence of greater within-woman variability in follicular versus luteal phase length [19].

Integrated Hormonal and Metabolic Profiling

Advanced metabolic studies combine hormonal phase determination with comprehensive biochemical profiling [22]:

- Multi-Phase Classification: Serum hormones (estradiol, progesterone, FSH, LH), urinary luteinizing hormone tests, and self-reported menstrual timing were integrated to establish a 5-phase cycle classification system.

- High-Throughput Metabolomics: Plasma and urine samples were analyzed using LC-MS and GC-MS platforms to quantify 397 metabolites and micronutrients across cycle phases.

- Statistical Analysis: Phase-to-phase comparisons were conducted with false discovery rate (FDR) correction to identify rhythmic metabolites, with 71 reaching FDR <0.20 threshold.

This approach revealed significant metabolic rhythmicity throughout the menstrual cycle, with 39 amino acids and derivatives and 18 lipid species decreasing during the luteal phase, providing biochemical correlates to phase-specific physiological states [22].

Endocrine Regulation of Follicular Phase Variability

The greater variability observed in the follicular phase stems from the complex endocrine regulation governing follicular development and ovulation. The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis coordinates this process through precisely timed hormonal interactions.

Figure 1: Hormonal Regulation of the Follicular Phase. The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis coordinates follicular development through pulsatile GnRH secretion, FSH stimulation, and estradiol-mediated positive feedback that triggers the LH surge and ovulation.

The follicular phase begins with the removal of negative feedback inhibition following the decline of progesterone, estrogen, and inhibin A from the previous cycle's corpus luteum [23]. This allows FSH levels to rise during the late luteal phase, recruiting a cohort of ovarian follicles. Typically, 11-20 eggs begin developing, but only one reaches full maturity as the dominant follicle [24]. The extended duration and complexity of this selection process, influenced by numerous factors, accounts for the greater variability observed in follicular versus luteal phase length.

Table 2: Factors Associated with Follicular Phase Length Variability

| Factor | Association with Follicular Phase Length | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Decreases by 0.19 days per year from age 25-45 [17] | Analysis of 612,613 cycles showing progressive shortening |

| Oral Contraceptive Use | Recent use (within 90 days) associated with 2.3-day lengthening [21] | Prospective cohort study with hormonal confirmation |

| Marijuana Use | Occasional use associated with 3.5-day lengthening [21] | Dose-response relationship observed |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Higher BMI (>35) associated with 0.4-day greater cycle variation [17] | Analysis of 124,648 app users |

| Miscarriage History | Associated with 2.2-day shortening [21] | Adjusted for age and OC use |

The transition from negative to positive feedback of estradiol at the anterior pituitary represents a critical threshold in follicular phase completion. This shift, which requires estradiol levels >200 pg/mL for approximately 50 hours, triggers the LH surge that initiates ovulation [20]. The time required to reach this threshold varies between cycles and individuals, contributing significantly to follicular phase variability.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following research tools and reagents are essential for conducting rigorous menstrual cycle phase analysis and hormone trend comparison studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Menstrual Cycle Studies

| Research Solution | Application | Function in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Urinary Estrone-3-Glucuronide (E1-3G) & Pregnanediol-3-Glucuronide (Pd-3G) Assays | Ovulation timing | Biomarkers for estimating day of ovulation via metabolite ratios [21] |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits for FSH, LH, Estradiol, Progesterone | Hormonal phase classification | Quantify serum hormone levels for precise cycle phase determination [22] |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) Platforms | Metabolic profiling | Identify and quantify rhythmic metabolites across menstrual phases [22] |

| Basal Body Temperature (BBT) Tracking Devices | Ovulation detection | Detect post-ovulatory temperature rise for phase length calculation [19] |

| Urinary Luteinizing Hormone (LH) Test Strips | Ovulation prediction | Identify LH surge preceding ovulation for fertile window identification [17] |

These research tools enable the precise hormone measurements and physiological monitoring necessary for comparing hormone trends across different menstrual cycle patterns. The combination of hormonal assays with metabolic profiling platforms represents particularly powerful methodology for comprehensive cycle phase analysis.

The collective evidence from large-scale observational studies, detailed hormonal monitoring, and metabolic profiling consistently identifies the follicular phase as the primary source of menstrual cycle variability. This understanding has profound implications for research design in women's health, drug development, and clinical practice. Studies investigating cycle-related phenomena must account for this inherent variability rather than assuming standardized phase lengths across populations. Future research should continue to elucidate the complex factors influencing follicular phase duration, including genetic predispositions, environmental influences, and physiological states. Such investigations will further refine our understanding of menstrual cycle dynamics and enhance our ability to interpret hormone trends across diverse cycle patterns.

Menstrual cycle characteristics are increasingly recognized as critical vital signs for overall health, with growing evidence linking long or irregular cycles to conditions such as infertility, cardiometabolic disease, and premature mortality [25] [26] [27]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the baseline variations in cycle patterns across different demographic groups is essential for designing clinical trials, interpreting real-world evidence, and developing targeted therapies. Historically, clinical guidelines for menstrual cycle parameters have been primarily based on studies of White populations, leaving significant gaps in our understanding of how these patterns manifest across diverse racial and ethnic groups [25] [26]. This guide synthesizes recent large-scale research to objectively compare how age, body mass index (BMI), race, and ethnicity influence menstrual cycle length and variability, providing a foundational reference for scientific and clinical applications.

Key Findings at a Glance

The following tables summarize the core quantitative relationships between demographic factors and menstrual cycle characteristics, based on aggregated data from large cohort studies including the Apple Women's Health Study (AWHS) which analyzed 165,668 cycles from 12,608 participants [25] [26] [27].

Table 1: Mean Cycle Length Differences by Demographic Factors (Reference: White, Age 35-39, Healthy BMI)

| Demographic Factor | Category | Mean Difference in Cycle Length (Days) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | <20 | +1.6 | +1.3 to +1.9 |

| 20-24 | +1.4 | +1.2 to +1.7 | |

| 25-29 | +1.1 | +0.9 to +1.3 | |

| 30-34 | +0.6 | +0.4 to +0.7 | |

| 40-44 | -0.5 | -0.3 to -0.7 | |

| 45-49 | -0.3 | -0.1 to -0.6 | |

| ≥50 | +2.0 | +1.6 to +2.4 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Asian | +1.6 | +1.2 to +2.0 |

| Hispanic | +0.7 | +0.4 to +1.0 | |

| Black | -0.2 | -0.1 to +0.6 | |

| BMI Category | Overweight | +0.3 | +0.1 to +0.5 |

| Class 1 Obese | +0.5 | +0.3 to +0.8 | |

| Class 2 Obese | +0.8 | +0.5 to +1.0 | |

| Class 3 Obese | +1.5 | +1.2 to +1.8 |

Table 2: Cycle Variability and Irregularity Patterns by Demographic Factors

| Demographic Factor | Category | Cycle Variability Change vs. Reference | Odds Ratio for Long Cycles | Odds Ratio for Short Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group (Ref: 35-39) | <20 | +46% | 1.85 | 0.90 |

| 45-49 | +45% | 1.72 | 2.44 | |

| ≥50 | +200% | 6.47 | 3.25 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref: White) | Asian | Increased | 1.43 | - |

| Hispanic | Increased | 1.26 | - | |

| BMI Category (Ref: Healthy) | Class 3 Obese | Increased | ~1.30* | - |

Note: Specific odds ratio estimates for BMI and short cycles were not fully reported in the available sources, though the association with long cycles is well-established [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The Apple Women's Health Study (AWHS) Protocol

The Apple Women's Health Study represents one of the most comprehensive large-scale digital cohorts for menstrual health research, with methodology designed for robust epidemiological analysis [25] [26] [27].

- Study Population and Eligibility: The analysis included 12,608 participants contributing 165,668 menstrual cycles. Participants were excluded if they reported a history of polycystic ovary syndrome, uterine fibroids, hysterectomy, or current hormone use to isolate natural menstrual patterns [25].

- Data Collection: Menstrual cycle data was collected through mobile tracking applications, with cycle length defined as the number of days from the first day of menstrual flow to the day before the next period begins. Survey data on demographic characteristics, including self-reported race, ethnicity, and BMI, were collected through the Common Demographics survey in the Apple Research App [25] [27].

- Statistical Analysis: Researchers employed linear mixed effects models to estimate differences in cycle length associated with age, race/ethnicity, and BMI, adjusted for potential confounders. Cycle variability was quantified using within-individual standard deviations of cycle length. The analysis specifically used the 35-39 age group as the reference for age-related comparisons because this group demonstrated the lowest cycle variability [26] [27].

Hormone Monitoring Protocol for Cycle Phase Characterization

A separate study utilizing at-home hormone monitoring technology provides insights into the endocrine mechanisms underlying demographic variations in cycle characteristics [28] [29].

- Hormone Tracking System: The study employed the Oova platform, a remote fertility testing system that quantitatively tracks luteinizing hormone (LH) and pregnanediol-3-glucuronide (PdG) through urine test cartridges. The system uses advanced nanotechnology that adjusts for pH, normalizes hydration levels, and filters out non-specific binding [28].

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Participants collected daily urine samples either through midstream or dip format. Test results were captured and interpreted by an AI-powered smartphone app that utilizes computer vision algorithms to adjust for lighting, shadows, and movement. The platform establishes each user's unique hormone baseline levels, with daily fluctuations compared to this personalized baseline rather than population averages [28].

- Cycle Phase Definitions: The follicular phase was defined as the period from the first day after bleeding cessation to the date of the peak LH level. The luteal phase was defined as the days from the first day after ovulation to the day before the next menstrual cycle. Ovulation was confirmed by detecting a rise in progesterone within 72 hours after the highest LH levels were detected [28].

Research Methodology for Demographic Menstrual Cycle Studies

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Materials and Technologies for Menstrual Cycle Studies

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Representative Use in Cited Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Menstrual Tracking Platforms | Large-scale cycle data collection | Mobile app interface, longitudinal design, real-time data capture | Apple Women's Health Study (165,668 cycles) [25] [27] |

| At-home Hormone Monitoring Systems | Quantitative LH and PdG tracking | Urine test cartridges, AI-powered analysis, personalized baselines | Oova platform for cycle phase characterization [28] |

| Demographic Survey Instruments | Collection of participant characteristics | Standardized questionnaires, self-reported race/ethnicity and BMI | Common Demographics survey in AWHS [25] |

| Statistical Modeling Approaches | Analysis of cycle variability | Linear mixed effects models, quantile regression | Analysis of age, BMI, and ethnic variations [26] [27] |

Biological Mechanisms and Pathways

The observed demographic variations in menstrual cycle characteristics are mediated through multiple endocrine pathways that respond to factors such as age, metabolic status, and potentially genetic or environmental influences associated with racial and ethnic backgrounds.

- Age-Related Hormonal Changes: With advancing age, particularly after 35-39 years, follicular phase length declines while luteal phase length may increase slightly, reflecting diminishing ovarian reserve and alterations in hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis function [28] [30]. The significant increase in cycle variability after age 45 (200% higher in those over 50 compared to ages 35-39) corresponds to the peri-menopausal transition characterized by erratic hormonal fluctuations and anovulatory cycles [25] [30].

- BMI and Hormonal Disruption: Obesity influences menstrual cycles through multiple mechanisms. Adipose tissue produces additional estrogen through aromatization of androgens, potentially disrupting the normal feedback mechanisms of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. This estrogen excess can suppress follicular development and ovulation, leading to longer and more variable cycles [25]. The dose-response relationship between BMI category and cycle length (from +0.3 days for overweight to +1.5 days for Class 3 obesity) supports this mechanistic pathway [26] [27].

- Racial and Ethnic Variations: The longer cycles observed in Asian and Hispanic participants compared to White women may reflect differences in hormonal levels or ovarian reserve across ethnic groups. Some studies have reported higher anti-Mullerian hormone levels among Hispanic and Asian women compared to White women of the same age, suggesting potential differences in follicular dynamics [31] [27]. Additionally, variations in exposure to social, cultural, and environmental stressors across different ethnic groups may contribute to these differences through effects on neuroendocrine function [25].

Biological Pathways Linking Demographics to Cycle Changes

Implications for Research and Drug Development

For researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, these findings have significant implications for clinical trial design and therapeutic development.

- Clinical Trial Design: Demographic stratification in trials evaluating reproductive therapies should account for the natural variations in cycle patterns across age, BMI, and ethnic groups. The established baselines enable more accurate participant selection and endpoint assessment [26] [27].

- Personalized Medicine Approaches: The documented differences in cycle characteristics support the development of demographic-specific parameters for evaluating menstrual health, moving beyond the historical one-size-fits-all approach based primarily on White populations [25] [32].

- Drug Efficacy Assessment: Understanding natural cycle variations enhances the ability to distinguish true treatment effects from demographic-driven baseline differences in studies of fertility treatments, hormonal therapies, and interventions for menstrual disorders [28] [27].

The comprehensive analysis of demographic influences on menstrual cycle parameters reveals complex interactions between age, BMI, race, and ethnicity that must be considered in both research and clinical contexts. The patterns established through large-scale digital cohort studies provide an evidence base for refining clinical guidelines and developing more personalized approaches to menstrual health. For the research and drug development community, these findings underscore the importance of demographic considerations in trial design, endpoint selection, and interpretation of results when evaluating therapies targeting reproductive health and endocrine function. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific genetic, environmental, and socioeconomic factors that drive the observed racial and ethnic differences in menstrual cycle characteristics.

Innovative Methodologies for Tracking Hormonal Shifts and Cycle Phases

The study of women's health, particularly hormonal and menstrual physiology, has been historically constrained by reliance on infrequent clinical visits and subjective self-reporting. Digital biomarkers – defined as physiological, behavioral, and environmental data collected via digital devices like smartphones and wearables – are revolutionizing this field by enabling continuous, objective, and real-world data collection [33] [34]. These biomarkers provide unprecedented insights into the dynamic patterns of menstrual cycles, moving beyond the oversimplified "textbook" 28-day model. The global market for digital biomarkers is expanding rapidly, projected to grow from $5 billion in 2025 to $18.8 billion by 2030, reflecting their increasing adoption in medical research and clinical practice [34]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the digital biomarkers and methodologies currently transforming research on hormone trends and menstrual cycle patterns.

Comparative Analysis of Digital Biomarkers for Cycle Tracking

Different digital biomarkers offer distinct advantages and limitations for capturing the physiological changes associated with menstrual cycle phases. The table below compares the primary biomarkers used in large-scale app-based studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Digital Biomarkers for Menstrual Cycle Research

| Digital Biomarker | Physiological Correlation | Data Collection Method | Key Research Findings | Considerations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Body Temperature (BBT) | Rise in progesterone post-ovulation increases resting body temperature [35]. | Ear thermometers, intravaginal sensors, or wearable patches [36]. | Detects biphasic pattern confirming ovulation; mean luteal phase length is 12.4 days [37]. | Requires measurement at rest upon waking; cycle phase is determined retrospectively [35]. |

| Resting Heart Rate (RHR) | Influenced by estrogen and progesterone; tends to be lowest during menstruation and peaks in the luteal phase [38]. | Consumer wearables (e.g., WHOOP, Fitbit, Huawei Band) during sleep or rest. | Average increase of 2.73 BPM from follicular to luteal phase [38]. | Provides real-time, forward-looking insights; sensitive to confounders like illness, stress, and alcohol. |

| Heart Rate Variability (HRV) | Reflects autonomic nervous system balance, modulated by hormonal shifts [38]. | Consumer wearables (e.g., WHOOP, Fitbit, Huawei Band) during sleep or rest. | Average decrease of 4.65 ms from follicular to luteal phase [38]. | A higher value indicates better recovery; sensitive to the same confounders as RHR. |

| Physical Activity & Sleep | Hormonal changes can influence energy levels, sleep quality, and activity patterns. | Wearable accelerometers and gyroscopes. | Used in models for postpartum depression recognition; associated with stress and lifestyle factors [39] [37]. | Provides behavioral context; best used in combination with physiological biomarkers. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Digital Biomarkers

To ensure the validity and reliability of digital biomarker data, researchers employ rigorous experimental protocols. The following section details key methodologies from recent landmark studies.

Protocol for Fertile Window and Menses Prediction

A prospective observational cohort study conducted in Shanghai aimed to develop machine-learning algorithms for predicting the fertile window and menstruation using BBT and heart rate.

- Study Population and Design: The study recruited 89 regular menstruators and 25 irregular menstruators, following them for at least four menstrual cycles. Participants were healthy women aged 18-45, excluded if they had major diseases, were breastfeeding, or were taking hormone-interfering medications [35].

- Data Collection:

- Basal Body Temperature (BBT): Measured daily upon waking using an ear thermometer (Braun IRT6520) after lying horizontally for 5 minutes [35].

- Heart Rate (HR): Recorded continuously during sleep using the Huawei Band 5, worn every night. Data was synced with a smartphone each morning [35].

- Ovulation Confirmation (Gold Standard): Determined via transvaginal/abdominal ultrasound and serum hormone level measurements (LH, E2, FSH, progesterone). Monitoring began between cycle days 8-12 and continued until follicle rupture was confirmed [35].

- Data Analysis: The cycles were divided into menstrual, follicular, fertile (5 days before to day of ovulation), and luteal phases. Linear mixed models assessed parameter changes, and probability function estimation models with machine learning were developed for prediction [35].

- Key Outcome: The algorithm combining BBT and HR predicted the fertile window in regular menstruators with an accuracy of 87.46% (AUC=0.8993) and menses with 89.60% accuracy [35].

Protocol for Large-Scale Menstrual Cycle Characterization

A study published in npj Digital Medicine analyzed over 600,000 cycles from the Natural Cycles app to establish real-world cycle characteristics and their associations with age and BMI.

- Data Source: Anonymized data from 124,648 users, including 17.4 million BBT measurements and user-inputted information on menstruation, age, and BMI [37].

- Cycle Selection: From 1.4 million recorded cycles, 612,613 ovulatory cycles with valid temperature data entered on at least 50% of days were included. Ovulation was estimated by the app's algorithm based on the BBT rise [37].

- Validation: The algorithm's Estimated Day of Ovulation (EDO) was validated by comparing the distributions of follicular and luteal phase lengths to established clinical data sets from Baird et al. and Lenton et al. [37].

- Key Findings:

- The mean cycle length was 29.3 days, with a mean follicular phase of 16.9 days and a mean luteal phase of 12.4 days.

- Only 16% of women exhibited the classic 28-day cycle, and only 12% had a consistent 28-day cycle with ovulation on day 14 [40] [37].

- Cycle and follicular phase length decreased with age (~0.18 and ~0.19 days per year from age 25-45), while luteal phase length remained stable [37].

Protocol for Postpartum Depression (PPD) Recognition

A cross-sectional study using the All of Us Research Program data set explored the use of consumer wearables for recognizing postpartum depression.

- Data Source and Cohort: Analysis utilized the Registered Tier v6 data set. The cohort included women with valid Fitbit data who gave birth, comprising fewer than 20 with PPD and 39 without PPD [39].

- Digital Biomarkers: Features extracted from Fitbit data included:

- Heart Rate Metrics: Daily average, SD, minimum, maximum, and quartile values.

- Physical Activity: Total daily steps.

- Energy Expenditure: Calories burned, including basal metabolic rate (BMR) [39].

- Machine Learning Modeling: Intraindividual models were built using algorithms like Random Forest, Generalized Linear Models, SVM, and k-NN to classify four periods: prepregnancy, pregnancy, postpartum without depression, and postpartum with depression (PPD) [39].

- Key Findings:

- Random Forest models performed best (mAUC=0.85; κ=0.80) at discerning the PPD period.

- The most predictive biomarker for PPD was calories burned during the basal metabolic rate.

- Individualized models surpassed the performance of traditional cohort-based models [39].

Visualization of Research Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for employing digital biomarkers in menstrual cycle and women's health research, as demonstrated by the cited protocols.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for digital biomarker research in women's health, illustrating the sequence from participant recruitment to data-driven insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing studies in this domain, the following table details key digital and analytical "reagents" and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagent Solutions for Digital Biomarker Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Wearables | Huawei Band 5, Fitbit devices, WHOOP | Continuous, passive collection of physiological data (HR, HRV, activity, sleep) in real-world settings. | Facilitates large-scale, longitudinal data acquisition; consumer-grade acceptability [35] [39] [38]. |

| Specialized Sensors | Braun IRT6520 ear thermometer, OvuSense intravaginal logger | High-fidelity measurement of specific biomarkers like BBT for precise ovulation detection. | Provides clinical-grade accuracy for validating consumer device data or for primary endpoint measurement [36] [35]. |

| Data Integration & Analytics Platforms | Natural Cycles app algorithm, custom ML pipelines (R, Python) | Processes raw sensor data, integrates multi-modal inputs, and applies statistical and ML models for analysis and prediction. | Enables handling of large, complex datasets; crucial for feature engineering and model development [35] [37]. |

| Validation Tools (Gold Standards) | Transvaginal ultrasound, serum hormone assays (LH, E2, FSH, progesterone) | Provides ground-truth data for confirming ovulation and menstrual cycle phases to validate digital biomarker algorithms. | Essential for establishing the clinical validity and regulatory credibility of digital biomarker endpoints [35]. |

Discussion and Research Implications

The integration of digital biomarkers from app-based studies is providing a more nuanced and accurate picture of menstrual cycle patterns and their relationship to women's health. Key insights confirm significant individual variability, debunking uniform models like the 28-day cycle [40] [37]. The emergence of novel metrics, such as Cardiovascular Amplitude from WHOOP, which quantifies RHR and HRV fluctuations across the cycle, offers new avenues for assessing cycle regularity and hormonal health beyond mere length tracking [38].

These methodologies also hold profound implications for drug development and clinical trials. Digital biomarkers can streamline data collection, providing continuous, objective endpoints that are more sensitive than episodic clinic visits [33] [34]. This is particularly relevant for conditions like postpartum depression, where individualized models using wearable data show promise for early recognition, potentially enabling timely intervention [39].

However, challenges remain, including data standardization, device validation, and navigating regulatory landscapes for these novel endpoints [33] [34]. Furthermore, researchers must account for confounding factors such as age, baseline fitness, and hormonal contraceptive use, which can modulate digital biomarker signals [38]. Despite these hurdles, the objective, high-resolution data afforded by digital biomarkers is undeniably advancing women's health research from a paradigm of averages to one of personalized, dynamic understanding.

For decades, the clinical and research communities have relied on a limited toolkit for menstrual cycle and ovulation tracking, with Basal Body Temperature (BBT) charting being one of the most common methods. Despite its widespread use, BBT is characterized by significant limitations, including low sensitivity (approximately 22%) in detecting ovulation and a high susceptibility to disruption by environmental factors, sleep irregularities, and measurement inconsistencies [41]. The imperative for more reliable and sophisticated methodologies has catalyzed the exploration of novel, non-invasive technologies. This guide objectively compares the performance of emerging methods—vocal acoustic analysis, continuous wrist temperature sensing, wearable cardiovascular monitoring, and integrated wearable biosensors—against traditional BBT and each other. It is framed within broader research on comparing hormone trends across different menstrual cycle patterns, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a data-driven overview of the next generation of cycle tracking technologies.

Performance Comparison of Emerging Tracking Methods

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics and characteristics of emerging non-invasive tracking methods compared to the traditional BBT approach.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Non-Invasive Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Tracking Methods

| Tracking Method | Reported Ovulation Detection Accuracy/Performance | Key Measured Parameters | Data Collection Protocol | Advantages for Hormone Trend Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vocal Acoustic Analysis | • 81% of participants showed vocal shift within fertile window (Fundamental Frequency SD & 5th percentile) [42] | • Fundamental frequency (mean, SD, 5th/95th percentile) [42] | • Daily voice recordings of fixed phrase upon waking [42] | • Captures subtle, hormone-driven tissue hydration changes [42] • Highly scalable via smartphones [42] |

| Continuous Wrist Skin Temperature | • Sensitivity: 0.62 (vs. 0.23 for BBT) [43] • True-positive rate: 54.9% (vs. 20.2% for BBT) [43] | • Wrist skin temperature (99th percentile during sleep) [43] | • Worn during sleep, requires ≥4 hours of uninterrupted data [43] | • Captures circadian rhythm temperature variations missed by point measurements [43] • Higher sensitivity for detecting ovulatory shifts [43] |

| Wearable Cardiovascular Monitoring | • RHR peaks at cycle day 26, RMSSD nadir at day 27 (population-level, n=11,590) [44] • Fluctuation pattern is attenuated with hormonal birth control [44] | • Resting Heart Rate (RHR) • Heart Rate Variability (RMSSD) [44] | • Continuous wrist-worn PPG sensor [44] • Longitudinal tracking across cycles [44] | • Provides large-scale, objective physiological data on cycle variability [44] • Links cardiovascular dynamics to hormonal fluctuations [44] |

| Smart Menstrual Health Patch | • 92.3% accuracy in ovulation prediction vs. LH tests [45] | • Basal Body Temperature • Hormone fluctuations (estrogen, progesterone via interstitial fluid) [45] | • Continuous wear across multiple cycles [45] | • Multi-parameter data fusion (temperature + direct hormone markers) [45] • Potential for identifying cycle disorders (PCOS, endometriosis) [45] |

| Traditional BBT (Oral) | • Sensitivity: ~0.23 [43] • Approx. 22% accuracy in detecting ovulation [41] | • Single-point oral temperature upon waking [41] | • Measured immediately upon waking, before any activity [41] | • Established, low-cost method [41] • Clear biphasic pattern in ovulatory cycles [41] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Vocal Acoustic Analysis for Fertility Tracking

A 2025 JMIR Formative Research study provides a robust protocol for longitudinal vocal analysis [42].

Objective: To explore how fundamental frequency (F0) features vary between menstrual phases using daily voice recordings and to apply changepoint detection to pinpoint the day of vocal shifts [42].

Participant Cohort:

- 16 naturally cycling, English-speaking, cis-gender female participants.

- All reported consistent menstrual cycles (1-4 days variation) and were not using hormonal birth control [42].

Data Collection Workflow:

- Daily Protocol: Upon waking each morning, participants performed three tasks:

- Voice Recording: Recorded themselves saying "Hello, how are you?" in a quiet environment using a custom mobile app.

- Hormone Test: Self-administered a consumer-grade luteinizing hormone (LH) urine test (Easy@Home Ovulation Tests) and took a picture of the result.

- BBT Measurement: Measured and recorded their basal body temperature.

- Timing: Data collection began the day after menstruation ended and continued for one full menstrual cycle.

- Data Management: All data was submitted via the mobile app to a secure cloud database [42].

Analytical Workflow:

- Feature Extraction: Fundamental frequency features (mean, standard deviation, 5th percentile, and 95th percentile) were extracted from each voice recording.

- Phase Comparison: F0 features were compared between the follicular and luteal phases, identified via the LH surge.

- Changepoint Detection: Applied to each feature's longitudinal data to identify the specific day when vocal behavior statistically shifted [42].

Key Quantitative Findings:

- Fundamental Frequency SD: 9.0% lower in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase.

- 5th Percentile of F0: 8.8% higher in the luteal phase.

- For the significant features (F0 SD and 5th percentile), 81% of participants exhibited changepoints within their fertile window [42].

Figure 1: Vocal Acoustic Analysis Experimental Workflow

Continuous Wrist Temperature Sensing

A 2021 prospective comparative study established a protocol for comparing wrist skin temperature to BBT [43].

Objective: To determine the diagnostic accuracy of continuously measured wrist skin temperature during sleep versus oral BBT for detecting ovulation, using LH tests as a reference standard [43].

Participant Cohort:

- 57 healthy women contributing 193 cycles (170 ovulatory, 23 anovulatory).

- Aged 18-45, not on hormonal therapy, and without conditions affecting menstrual cycles [43].

Data Collection Workflow:

- Wrist Temperature: Participants wore an Ava Fertility Tracker bracelet (v2.0) on the dorsal side of the wrist during sleep each night. The first 90 and last 30 minutes of data were excluded, and the 99th percentile of the remaining data was used as the daily temperature value [43].

- BBT: Measured orally each morning immediately upon waking using a Lady-Comp digital thermometer [43].

- LH Test: ClearBlue Digital Ovulation Tests were performed daily starting from a cycle day calculated based on the participant's average cycle length until a surge was detected or menstruation began [43].

Analytical Workflow:

- Ovulation was defined as the day following the LH surge.

- Diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity) of temperature shifts detected by each method was calculated against the LH reference.

- Correlation and agreement between the two temperature curves were analyzed across menstrual phases [43].

Large-Scale Cardiovascular Fluctuation Analysis

A 2024 npj Digital Medicine study introduced a novel metric for quantifying menstrual cycle-related cardiovascular changes [44].

Objective: To derive a "cardiovascular amplitude" metric quantifying fluctuations in resting heart rate (RHR) and heart rate variability (RMSSD) across the menstrual cycle and investigate its association with age, BMI, and birth control use [44].

Participant Cohort:

- 11,590 participants (9,968 naturally cycling, 1,661 using birth control pills).

- Over 45,811 unique menstrual cycles and 1.24 million days of data from a global population [44].

Data Collection Workflow:

- Participants used wrist-worn devices with photoplethysmography (PPG) capabilities to continuously monitor RHR and RMSSD.

- Menstrual cycle data (start and end of bleeding) was self-reported via connected apps [44].

Analytical Workflow:

- Population Modeling: Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs) established the population-level relationship between cycle day and RHR/RMSSD offsets from the cycle mean.

- Cardiovascular Amplitude (RHRamp/RMSSDamp): Defined for RHR as the mean of the final 7 days of the cycle minus the mean of days 2-8. For RMSSD, it was the mean of days 2-8 minus the mean of the final 7 days.

- Cohort Analysis: GLMs assessed the association of amplitude with age, BMI, and birth control status [44].

Key Findings:

- RHR: Nadir near cycle day 5, peak near day 26.

- RMSSD: Peak near cycle day 5, nadir near day 27.

- Amplitude Attenuation: Cardiovascular amplitude was significantly reduced in older participants and those using hormonal birth control, reflecting dampened hormonal fluctuations [44].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Vocal Acoustic and Menstrual Cycle Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Example Products / Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer LH Urine Tests | Reference standard for pinpointing ovulation and the LH surge in experimental protocols. | Easy@Home Ovulation Tests [42], ClearBlue Digital Ovulation Test [43] |

| Fundamental Frequency (F0) Analysis Software | Extracts quantifiable pitch-related acoustic features (mean, SD, percentiles) from voice recordings for statistical analysis. | Custom analysis scripts (e.g., Python, Praat) for F0 feature extraction [42] |

| Wrist-Worn Wearable Sensors | Enables continuous, passive monitoring of physiological parameters (temperature, RHR, HRV) during sleep or daily life. | Ava Fertility Tracker bracelet [43], Commercial PPG-based activity trackers [44] |

| Digital Basal Body Thermometers | Provides a digital, precise point measurement for oral BBT as a baseline comparison for novel methods. | Lady-Comp computerized fertility tracker [43] |

| Custom Mobile Data Collection Apps | Standardizes and centralizes longitudinal data collection (voice, test results, BBT) in a real-world setting. | Klick Applied Science custom app [42] |

| Changepoint Detection Algorithms | Identifies the precise statistical moment (day) when a longitudinal data stream (e.g., vocal features) shifts behavior. | Applied to F0 feature time series to identify fertile window transition [42] |

Logical Pathway from Hormonal Shift to Detectable Signal

The physiological pathways linking hormonal fluctuations to measurable non-invasive signals are complex. The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from hormonal shifts to the detectable signals captured by the methods discussed in this guide.

Figure 2: Hormonal Shift to Detectable Signal Pathway

The emerging landscape of non-invasive menstrual cycle tracking extends far beyond the limitations of traditional BBT. Vocal acoustic analysis offers a highly scalable, smartphone-based method that captures subtle, hormone-induced tissue changes. Continuous wrist temperature and wearable cardiovascular monitoring provide more sensitive, objective, and longitudinal physiological data streams, enabling a more nuanced view of the menstrual cycle's impact on core physiology. The experimental data confirms that these methods generally offer superior sensitivity and richer datasets for researching hormone trends across diverse cycle patterns compared to BBT.

A critical challenge for the field, particularly for vocal biomarkers, is the current lack of standardized master protocols for data collection and analysis, which can hinder reproducibility and cross-study comparison [46]. Future research should focus on establishing these standards and further validating these technologies in larger, more diverse populations. For researchers and drug development professionals, these technologies open new avenues for investigating cycle-related disorders, the impact of pharmaceuticals on menstrual health, and the fundamental interplay between hormones and broader physiology.

The luteinizing hormone (LH) surge is a definitive endocrine event in the human menstrual cycle, characterized by an abrupt, substantial rise in luteinizing hormone secretion from the anterior pituitary gland. This hormonal surge serves as the primary trigger for ovulation, typically occurring approximately 35–44 hours after surge onset and 10–12 hours after the LH peak [47]. The precise detection of this surge is therefore critical for multiple applications in reproductive medicine, including fertility planning, timed intercourse, and artificial reproductive techniques [48] [47]. From a research perspective, accurate LH surge identification enables scientists to establish temporal relationships between ovulation and other physiological parameters, facilitating investigations into how hormone fluctuations affect metabolic processes, physical performance, and health outcomes across different menstrual cycle patterns [49].

The LH surge results from a complex neuroendocrine signaling cascade originating in the hypothalamus. Under the influence of rising estradiol levels produced by the dominant follicle, the anterior pituitary gland releases a massive bolus of LH into the bloodstream [50]. This LH surge induces the resumption of meiosis in the oocyte and triggers the rupture of the follicular wall, leading to ovulation [47]. The urinary detection of LH metabolites provides a non-invasive alternative to serum measurements while maintaining high diagnostic accuracy, with studies demonstrating that a positive urinary LH test predicts ovulation within 48 hours with high reliability [47].

Gold Standard Methodologies for LH Surge Detection

Laboratory-Based Reference Methods

The clinical gold standard for detecting ovulation is transvaginal ultrasonography, which visualizes follicular development, rupture, and corpus luteum formation [47]. However, for specifically identifying the LH surge, serial serum LH measurements via immunoassay represent the biochemical gold standard. These laboratory-based methods provide quantitative LH values with high sensitivity and specificity but require repeated venipuncture, making them impractical for routine clinical use or long-term research studies [47] [51].

For research applications, especially those requiring precise cycle phase identification, urinary LH detection combined with urinary pregnanediol-3-glucuronide (PdG) measurement provides a practical yet accurate alternative. PdG, a metabolite of progesterone, rises following ovulation and provides retrospective confirmation that ovulation has occurred [48] [47]. This combined approach enables researchers to precisely identify the fertile window and confirm ovulation in study populations without the need for frequent blood draws [28].

Methodological Considerations for Urinary LH Detection

A comprehensive comparison of published methodologies for determining the onset of the LH surge in urine has identified three major methodological categories distinguished by how baseline LH levels are established [48]:

- Method #1 (Fixed Days): Uses fixed cycle days for baseline assessment without prior cycle information.

- Method #2 (Peak-Based): Determines baseline days based on the identified peak LH day.

- Method #3 (Retrospective Estimation): Uses a provisional estimate of the LH surge day to identify the appropriate baseline period.

Research comparing these methods on 254 ovulatory cycles from 227 women found that the most reliable approach for calculating baseline LH utilized 2 days before the estimated surge day plus the previous 4-5 days [48]. This method requires retrospective estimation of the LH surge day to identify the most appropriate part of the cycle for baseline calculation. The surge itself is typically defined as the first sustained rise in LH levels to at least 2.5-fold the standard deviation above the mean baseline level [48]. These methodological differences significantly impact LH surge day determination, highlighting the importance of consistent methodology when comparing across studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Methodologies for Determining Urinary LH Surge Onset

| Method Category | Baseline Determination | Pros | Cons | Research Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Days (Method #1) | Predetermined cycle days | Simple, requires no prior cycle information | Less accurate with cycle length variability | Limited for precise phase mapping |

| Peak-Based (Method #2) | Based on identified peak LH day | More personalized to individual cycle | Requires complete cycle data | Moderate for retrospective analysis |