Estradiol and Cognitive Performance: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Therapeutic Implications

This article synthesizes current research on the multifaceted mechanisms by which estradiol modulates cognitive performance.

Estradiol and Cognitive Performance: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the multifaceted mechanisms by which estradiol modulates cognitive performance. It explores the foundational neurobiology, including genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways, receptor distribution, and key brain regions such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. The review critically assesses methodological approaches in both clinical and preclinical settings, highlighting the impact of formulation, timing, and administration route on cognitive outcomes. It addresses challenges in therapeutic application, including the critical period hypothesis and individual risk factors, and provides a comparative analysis of estradiol-based therapies against other hormonal and non-hormonal targets. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis aims to bridge foundational science with clinical translation for the development of targeted cognitive therapeutics.

The Neurobiological Basis: How Estradiol Modulates Brain Function and Cognition

Estradiol, the most potent estrogen, exerts profound influence on brain function through two distinct classes of signaling mechanisms: genomic and non-genomic pathways. The genomic pathway represents the classical mechanism involving nuclear estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) acting as ligand-dependent transcription factors to regulate gene expression over hours to days [1] [2]. In contrast, the non-genomic pathway encompasses rapid signaling events (within seconds to minutes) initiated at the plasma membrane or in the cytoplasm, independently of direct transcriptional regulation [3] [4]. These pathways collectively mediate estradiol's effects on neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, cognitive function, and neuroprotection, with significant implications for understanding hormonal influences on brain health and disease pathogenesis.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Genomic vs. Non-Genomic Estradiol Signaling

| Feature | Genomic Signaling | Non-Genomic Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Profile | Slow (hours to days) | Rapid (seconds to minutes) |

| Primary Receptors | Nuclear ERα, ERβ | Membrane-associated ERα, ERβ, GPER1 |

| Signaling Initiation | Intranuclear receptor binding | Membrane/cytoplasmic activation |

| Key Mechanisms | Gene transcription via ERE/AP-1/Sp1 | Kinase activation (MAPK, PI3K/Akt), Ca²⁺ flux |

| Biological Outcomes | Protein synthesis, long-term plasticity | Rapid neuromodulation, synaptic efficacy |

| Experimental Inhibition | Transcription inhibitors (actinomycin D) | Kinase inhibitors, receptor antagonists |

Genomic Signaling Mechanisms

Classical Transcriptional Regulation

The genomic pathway begins with estradiol passively diffusing across the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope due to its lipophilic nature [1]. Inside the nucleus, estradiol binds to classical estrogen receptors ERα or ERβ, prompting receptor dimerization and binding to specific DNA sequences known as estrogen response elements (EREs) located in promoter regions of target genes [1] [2]. The ligated receptor complex recruits co-regulator proteins that modify chromatin structure and facilitate the assembly of the transcriptional machinery, ultimately leading to regulated expression of target genes [1].

This mechanism results in the synthesis of new proteins that underlie long-term functional and structural changes in neurons. Key neuroprotective genes induced through genomic signaling include neurotrophic factors (nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophins 3 and 4, insulin-like growth factor 1), anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-x), and proteins that maintain cellular architecture such as neurofilament and microtubulin-associated proteins [1].

Non-ERE-Dependent Genomic Regulation

Beyond the classical ERE-mediated transcription, estrogen receptors can regulate gene expression through protein-protein interactions with other DNA-binding transcription factors. ERs can dock to AP-1 transcription factors and influence gene transcription in the absence of an ERE [5]. Similarly, interaction with Sp1 transcription factors enables regulation of genes like CCND1 (coding for cyclin D1) through Sp1-binding sites in their promoter regions [5]. This mechanism significantly expands the repertoire of genes amenable to estrogenic regulation beyond those containing canonical ERE sequences.

Non-Genomic Signaling Mechanisms

Membrane-Initiated Estradiol Signaling

Non-genomic signaling is characterized by rapid cellular responses that occur too quickly to involve transcription and translation. These effects are mediated through estrogen receptors localized at or near the plasma membrane, including membrane-associated forms of ERα, ERβ, and the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1) [3] [4].

A key mechanism enabling membrane localization of classical ERs involves post-translational palmitoylation. This reversible lipid modification, catalyzed by palmitoyl acyltransferase enzymes DHHC7 and DHHC21, increases receptor lipophilicity and facilitates association with lipid membranes [3]. Mutation of the ER palmitoylation site eliminates membrane function while preserving nuclear activity, demonstrating the functional segregation of these signaling pathways [3].

Receptor Complexes and Signaling Cascades

Membrane estrogen receptors functionally couple with various signaling systems. In neurons, ERα and ERβ have been shown to functionally couple to group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), initiating mGluR signaling upon estradiol stimulation independent of glutamate [3]. This interaction is facilitated by caveolin proteins (Cav1-3) which organize signaling molecules into functional microdomains, with Cav1 and Cav3 generating distinct signaling complexes that isolate estrogen activation of group I from group II mGluR signaling [3].

Table 2: Major Non-Genomic Estradiol Signaling Pathways in the Brain

| Signaling Pathway | Initial Events | Key Effectors | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Src/Ras/ERK Cascade | Src activation, Ras phosphorylation | ERK1/2, CREB | Neuritogenesis, synaptic plasticity |

| PI3K/Akt Pathway | PI3K recruitment, PIP3 formation | Akt, eNOS, GSK-3β | Cell survival, metabolic regulation |

| Ca²⁺ Signaling | Mobilization of intracellular Ca²⁺ | CaMKII, PKC | Neurotransmitter release, excitability |

| cAMP Pathway | Adenylate cyclase activation | PKA, CREB | Gene expression, synaptic plasticity |

| mGluR Coupling | ER-mGluR functional interaction | IP₃, DAG | Neural excitability, behavior |

Upon estradiol binding, these membrane-associated receptor complexes activate multiple intracellular signaling cascades:

MAPK/ERK Pathway: Estradiol activates c-Src, leading to phosphorylation of Shc and subsequent Ras activation, which initiates the MAPK cascade resulting in ERK phosphorylation and activation of transcription factors like CREB [6]. This pathway plays a central role in the neuritogenic actions of estradiol [6].

PI3K/Akt Pathway: Estradiol stimulates PI3K activity, leading to Akt phosphorylation which promotes neuronal survival through inhibition of pro-apoptotic factors and activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [1] [4].

Calcium Signaling: Estradiol rapidly modulates intracellular calcium concentrations, affecting neuronal excitability and synaptic function through activation of calcium-dependent enzymes [4].

The dynamics of membrane ER signaling are tightly regulated. Estradiol initially promotes ERα trafficking to the membrane, then induces receptor internalization via phosphorylation by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) and recruitment of β-arrestin-1, which links ERα to the AP-2 adaptor complex for clathrin-mediated endocytosis [3]. This internalization both curtails signaling and facilitates endosomal signaling, extending cellular responsiveness [3].

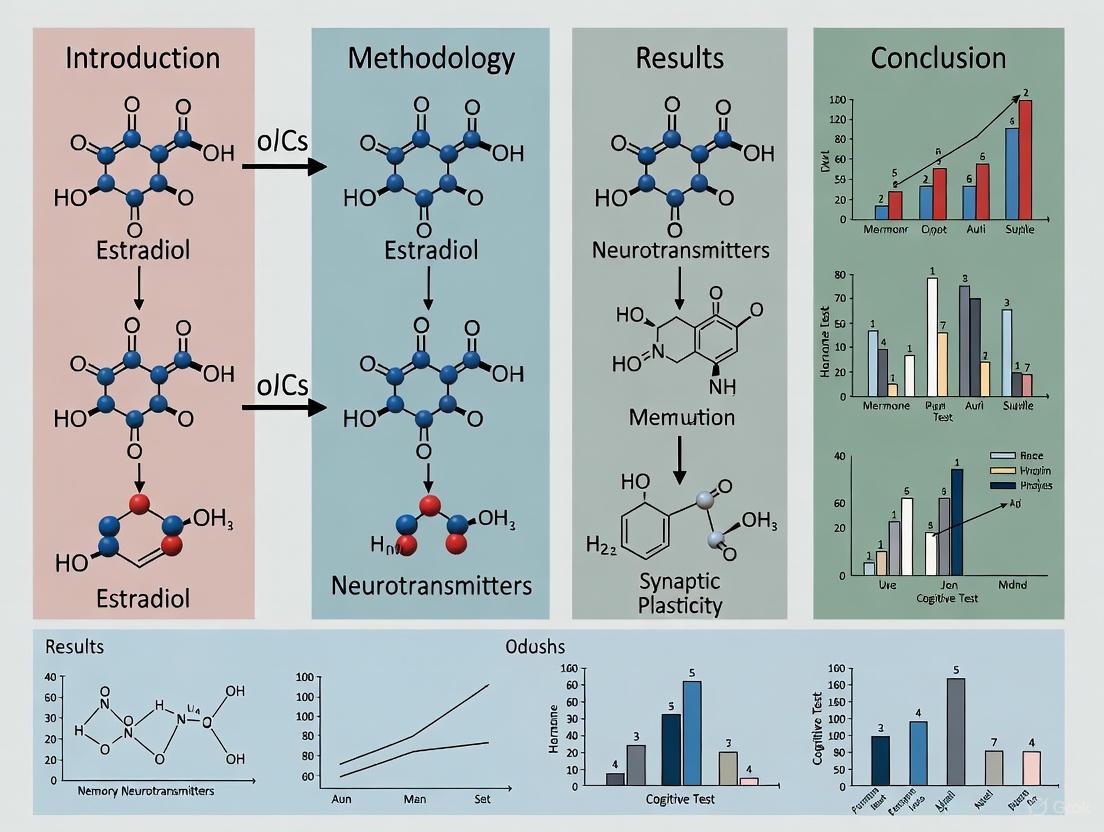

Diagram 1: Genomic and non-genomic estradiol signaling mechanisms in neurons.

Signaling Cross-Talk and Integration

Transcriptional Cross-Talk

The genomic and non-genomic pathways do not operate in isolation but engage in extensive cross-talk. Non-genomic signaling can indirectly influence gene expression through kinase-mediated phosphorylation of transcription factors and co-regulators. For instance, activation of the Src/Ras/Erk cascade by estradiol leads to phosphorylation of nuclear ER and other transcription factors, modulating their transcriptional activity [5]. This mechanism enables integration of rapid membrane-initiated signals with longer-term genomic responses.

Evidence for this cross-talk comes from studies showing that inhibition of the Src/Ras/Erk pathway with PD 98059 partially suppresses transcription of ER target genes (TFF1, ER, PR, BRCA1) induced by estradiol and certain xenoestrogens [5]. Similarly, estradiol activation of PI3K/Akt signaling modulates the activity of various transcription factors involved in cell survival and metabolism [1].

Interaction with Neurotrophic Signaling

Estradiol signaling extensively interacts with neurotrophic factor pathways, particularly brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) signaling [6]. Estradiol increases BDNF expression through genomic mechanisms while simultaneously activating BDNF signaling pathways through non-genomic mechanisms. Similarly, estradiol and IGF-I show synergistic activation of both MAPK and PI3K cascades, enhancing neuritogenesis beyond what either signal achieves independently [6].

Estradiol also modulates Notch signaling, which inhibits neurite outgrowth. In hippocampal neurons, estradiol inhibits Notch signaling through GPR30, thereby promoting dendritic complexity [6]. These interactions demonstrate how estradiol coordinates multiple signaling systems to regulate neuronal development and plasticity.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Investigating Genomic Signaling

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assays:

- Purpose: Identify direct binding of estrogen receptors to genomic DNA at EREs or other regulatory elements.

- Methodology: Crosslink proteins to DNA with formaldehyde, immunoprecipitate ER-DNA complexes using specific antibodies, reverse crosslinks, and quantify target sequences by PCR or sequencing [1].

- Key Applications: Mapping ER binding sites genome-wide, characterizing receptor interactions with non-ERE promoter elements (AP-1, Sp1 sites).

Gene Expression Profiling:

- Purpose: Comprehensive analysis of transcriptional programs regulated by estradiol.

- Methodology: RNA sequencing or microarray analysis of cells or tissue samples treated with estradiol versus vehicle control, with or without transcription inhibitors.

- Key Applications: Identification of estrogen-target genes, distinction between primary and secondary transcriptional responses [5].

Analyzing Non-Genomic Signaling

Kinase Activity Assays:

- Purpose: Measure rapid activation of signaling cascades following estradiol treatment.

- Methodology: Western blot analysis using phospho-specific antibodies for activated kinases (p-ERK, p-Akt, p-Src) at short time points (2-30 minutes) after estradiol exposure [3] [5].

- Pharmacological Inhibition: Use of specific inhibitors (PD 98059 for MEK, LY294002 for PI3K, ICI 182,780 for ER) to establish pathway specificity and ER dependence.

Calcium Imaging:

- Purpose: Visualize rapid estradiol-induced changes in intracellular calcium concentrations.

- Methodology: Load cells with fluorescent calcium indicators (Fura-2, Fluo-4), treat with estradiol, and monitor fluorescence changes in real-time using confocal microscopy [4].

- Key Applications: Demonstrate rapid signaling independent of transcription, characterize spatial and temporal dynamics of calcium signaling.

Membrane Receptor Localization:

- Purpose: Establish plasma membrane localization of estrogen receptors.

- Methodology: Cell fractionation followed by Western blotting, immunofluorescence with membrane markers, biotinylation of surface proteins [3].

- Palmitoylation Inhibition: Use of 2-bromopalmitate or DHHC enzyme knockdown to disrupt membrane localization and test functional consequences [3].

Table 3: Experimental Models for Studying Estradiol Signaling in the Brain

| Model System | Key Applications | Methodological Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Neuronal Cultures | Neurite outgrowth, synapse formation, rapid signaling | Maintain relevant neuronal phenotypes, hormone deprivation |

| Immortalized Cell Lines (e.g., HT-22, MCF-7) | Signaling pathway mapping, receptor trafficking | May lack complete neuronal characteristics |

| Brain Explants/Organotypic Cultures | Circuit-level responses, cellular interactions | Preserve native architecture and some connectivity |

| Rodent OVX Model | Cognitive testing, neuroprotection, therapy evaluation | Surgical vs. natural menopause considerations |

| Transgenic Models (ER knockouts, reporter lines) | Receptor-specific functions, pathway necessity | Compensation during development, cell-type specificity |

Behavioral and Cognitive Assessments

Morris Water Maze:

- Purpose: Assess spatial learning and memory in rodent models of estrogen deficiency and replacement.

- OVX Model Methodology: Female rats undergo ovariectomy to remove endogenous estrogen source, followed by estradiol or vehicle treatment, then tested for acquisition and retention of platform location [7].

- Outcome Measures: Escape latency, path length, time in target quadrant during probe trial [7].

Domain-Specific Cognitive Testing:

- Purpose: Evaluate specific cognitive domains affected by estradiol in human populations.

- Methodology: Comprehensive test batteries assessing episodic memory, prospective memory, executive functions, processing speed, and visuospatial processing [8] [9].

- Clinical Applications: Correlate hormonal status, menopausal stage, and hormone therapy with cognitive performance across domains [8].

Diagram 2: Experimental approaches for investigating estradiol signaling mechanisms.

Functional Outcomes and Clinical Implications

Neuroprotection and Cognitive Function

Estradiol signaling through both genomic and non-genomic mechanisms exerts significant neuroprotective effects. Genomic signaling promotes neuronal survival through induction of anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-x) and down-regulation of pro-apoptotic factors (BAX) [1]. Non-genomic signaling provides rapid protection against excitotoxicity and oxidative stress through kinase-mediated pathways [1] [4].

Clinical and epidemiological studies demonstrate that earlier age at menopause is significantly associated with lower scores across multiple cognitive domains, including episodic memory, prospective memory, and executive functions [8]. Conversely, estradiol-based menopausal hormone therapy shows domain-specific benefits, with transdermal estradiol associated with higher episodic memory scores and oral estradiol with higher prospective memory scores [8]. The critical window hypothesis posits that timing of estrogen therapy initiation relative to menopause is crucial for cognitive benefits, with early intervention near menopause onset showing the most favorable outcomes [9].

Therapeutic Implications and Drug Development

Understanding the distinct mechanisms of genomic versus non-genomic signaling has important implications for therapeutic development. The ideal profile for neuroprotective agents might involve maximizing beneficial non-genomic signaling while minimizing potentially harmful genomic effects, particularly in reproductive tissues [1].

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) and estrogen derivatives that preferentially activate neuroprotective signaling pathways with reduced feminizing or proliferative effects represent promising approaches [1]. Additionally, administration route significantly influences therapeutic efficacy, with transdermal estradiol bypassing hepatic metabolism and achieving more favorable E2:E1 ratios compared to oral formulations [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Estradiol Signaling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER Agonists | 17β-estradiol (E2), PPT (ERα-specific), DPN (ERβ-specific) | Receptor-specific activation, pathway mapping | Distinguish ERα vs. ERβ mediated effects |

| ER Antagonists | ICI 182,780 (Faslodex), Tamoxifen, MPP (ERα-specific) | Receptor necessity, pathway blockade | Differentiate ER-dependent vs independent effects |

| Signaling Inhibitors | PD 98059 (MEK inhibitor), LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor), PP2 (Src inhibitor) | Pathway dissection, cross-talk analysis | Establish specific pathway contributions |

| Gene Expression Tools | siRNA/shRNA (ER knockdown), CRISPR/Cas9 (ER knockout) | Functional receptor studies | Determine necessity of specific receptors |

| Detection Reagents | Phospho-specific antibodies, ER subtype antibodies, calcium indicators | Pathway activation, localization studies | Visualize and quantify signaling events |

| Experimental Models | OVX rodents, ER knockout mice, neuronal cell cultures | In vivo and in vitro functional studies | Translate mechanistic insights to functional outcomes |

The mechanisms of estradiol action in the brain encompass both genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways that operate in a highly integrated manner to regulate neuronal function, plasticity, and survival. The genomic pathway mediates longer-term adaptive responses through regulation of gene expression, while non-genomic signaling enables rapid modulation of neuronal excitability and function. Extensive cross-talk between these pathways, combined with interactions with neurotrophic signaling systems, creates a complex regulatory network through which estradiol influences cognitive performance and neuroprotection.

Understanding the distinct yet interconnected nature of these signaling mechanisms provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic approaches for cognitive decline associated with estrogen deficiency during menopause and in neurodegenerative diseases. Future research focusing on tissue-specific and pathway-selective estrogenic compounds holds promise for maximizing cognitive benefits while minimizing potential risks associated with broader estrogen receptor activation.

The intricate modulation of cognitive performance by estradiol is fundamentally rooted in the precise neuroanatomical distribution and signaling dynamics of its receptors, estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ). These receptors are not uniformly distributed throughout the brain; instead, they exhibit region-specific expression patterns within hippocampal and prefrontal circuits that are critical for learning, memory, and executive function [10]. The differential localization of ER subtypes creates distinct signaling microenvironments that influence synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and neurotransmitter systems essential for cognitive processing [11] [12]. Understanding this precise receptor mapping provides a crucial foundation for deciphering estrogen's complex effects on cognitive performance and for developing targeted therapeutic interventions for cognitive disorders. This review synthesizes current evidence on ERα and ERβ distribution within cognitive circuits, examining their distinct roles, signaling mechanisms, and implications for maintaining brain health across the lifespan.

Regional Distribution Patterns of ERα and ERβ

Hippocampal Complex Distribution

The hippocampus, a structure vital for memory formation and spatial navigation, demonstrates a complex and dynamic expression of both estrogen receptors throughout development and adulthood. During human hippocampal development, both ERα and ERβ are expressed from mid-gestation (around 15-17 gestational weeks) through adulthood, with prominent expression in pyramidal cells of Ammon's horn and the dentate gyrus [11]. A seminal study on human postmortem tissue revealed that ERα expression is detectable in the cortical plate as early as 9 gestational weeks, with intensity decreasing during prenatal development but increasing again from birth to adulthood [11]. In contrast, ERβ appears later around 15 gestational weeks but persists widely throughout the adult cortex [11].

In the adult brain, ERβ demonstrates higher protein expression levels in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus compared to ERα, as confirmed by Western blot analyses [11]. This relative abundance suggests potentially different functional roles for these receptor subtypes in cognitive processing. Ultrastructural studies in rat models have further revealed that hippocampal estrogen receptors are strategically localized at both nuclear and extranuclear sites, including dendritic spines and presynaptic terminals, enabling them to rapidly influence synaptic transmission and plasticity [12].

Table 1: Developmental Expression Patterns of ERα and ERβ in Human Hippocampus and Cortex

| Developmental Period | ERα Expression | ERβ Expression | Primary Locations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Prenatal (9 GW) | High | Not detected | Proliferating zones, cortical plate |

| Mid-Prenatal (15-17 GW) | Decreasing | Emerging | Cortical plate, proliferating zones |

| Late Prenatal | Low | Increasing | Widespread cortical layers |

| Adulthood | Increased | High, widespread | Cortical layers II-VI, hippocampal pyramidal cells |

GW = Gestational Weeks

Prefrontal Cortex Distribution

The prefrontal cortex (PFC), which governs executive functions including working memory, decision-making, and cognitive flexibility, exhibits a distinct ER expression profile. Immunohistochemical analyses demonstrate that ERβ is widely distributed throughout cortical layers II-VI in the adult human brain, while ERα shows more restricted expression [11]. This extensive ERβ distribution in the PFC positions it to significantly influence higher-order cognitive processes.

Notably, ER density in the frontal cortex appears dynamically regulated by hormonal status, with evidence suggesting increased ER density in the frontal cortex after menopause, possibly representing a compensatory mechanism following estrogen decline [8]. This adaptive response highlights the plasticity of ER expression in response to hormonal changes and may contribute to the varied cognitive responses to hormone therapy observed at different menopausal stages.

Subcellular Localization and Implications

The subcellular compartmentalization of estrogen receptors critically determines their functional roles in neuronal signaling. Ultrastructural evidence has revealed that a significant population of ERα in hippocampal neurons is located at extranuclear sites, including dendritic spines, axon terminals, and mitochondrial membranes [12]. This strategic positioning enables estradiol to rapidly modulate synaptic transmission and intracellular signaling cascades without requiring genomic activation.

The presence of ERα at presynaptic terminals suggests presynaptic regulatory mechanisms, while postsynaptic localization positions estrogen receptors to directly influence postsynaptic density signaling and dendritic spine morphology [12]. These findings collectively support an expanded model of estrogen signaling that integrates both rapid membrane-initiated events and longer-term genomic regulation to fine-tune neuronal function in cognitive circuits.

Diagram 1: Dual Signaling Mechanisms of Estrogen Receptors in Cognitive Circuits. Estradiol activates both genomic (nuclear) and rapid (extranuclear) signaling pathways through ERα and ERβ to enhance synaptic plasticity and cognitive function.

Functional Implications for Cognitive Performance

Receptor-Specific Roles in Cognitive Domains

The distinct distribution patterns of ERα and ERβ enable these receptor subtypes to differentially regulate specific cognitive domains through their unique influences on hippocampal and prefrontal circuitry. Research indicates that ERβ activation appears particularly important for certain types of memory processing, as demonstrated by studies showing that ERβ agonism enhances extinction memory recall for heroin-conditioned cues in a sex-specific manner, with females showing greater sensitivity to ERβ modulation in the basolateral amygdala [13].

The preferential localization of ERβ in cortical layers II-VI positions it to integrate information across multiple cortical processing streams, potentially influencing cognitive flexibility and executive control [11]. In contrast, ERα's prominent expression in hippocampal pyramidal cells and its role in regulating spine density suggest a more specialized function in spatial memory and consolidation processes. This functional dissociation is further supported by observations that earlier age at menopause, which results in premature estrogen decline, is significantly associated with lower scores across multiple cognitive domains, including episodic memory, prospective memory, and executive functions [8].

Hormonal Therapy and Cognitive Outcomes

The timing, route of administration, and receptor specificity of estrogen-based interventions significantly influence their cognitive outcomes, reflecting the complex interplay between ER distribution and hormonal status. Clinical evidence indicates that transdermal estradiol preparations are associated with higher episodic memory scores, while oral estradiol is linked to better prospective memory performance [8]. This differential effect likely reflects variations in receptor activation patterns influenced by first-pass metabolism and the distinct E2:E1 ratios achieved through different administration routes.

The "critical window" hypothesis proposes that optimal cognitive benefits from estrogen therapy occur when initiated near menopause onset, before age-related brain changes become established [9]. This temporal sensitivity may reflect the dynamic nature of ER expression and the capacity for synaptic reorganization in response to estrogen fluctuations. Supporting this concept, studies show that hormone therapy started within approximately two years of oophorectomy is associated with better episodic memory, working memory, and visuospatial processing in later life [9].

Table 2: Cognitive Domain Sensitivity to Estrogen Receptor Modulation

| Cognitive Domain | Primary Neural Substrate | ER Subtype Involvement | Therapeutic Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic Memory | Hippocampus, Medial Temporal Lobe | ERα (hippocampal), ERβ (cortical) | Transdermal E2 beneficial |

| Executive Function | Prefrontal Cortex | ERβ (predominant in PFC) | Limited MHT response |

| Prospective Memory | Frontal & Medial Temporal Lobes | ERβ, possibly ERα | Oral E2 beneficial |

| Working Memory | Prefrontal Cortex, Hippocampus | Both ERα and ERβ | Hormone therapy post-oophorectomy beneficial |

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

Protocol: ER Distribution Mapping in Human Brain Development

Understanding the methodological approaches for mapping estrogen receptors provides critical context for interpreting distribution data and designing future studies.

Tissue Preparation and Sectioning:

- Obtain human brain specimens from gestational weeks 9 through adulthood, with postmortem intervals under 12 hours

- Fix tissue in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 24-48 hours

- Cryoprotect in 30% sucrose solution until sinking

- Section coronally at 40μm thickness using a freezing microtome

- Collect serial sections systematically throughout hippocampal and prefrontal regions

Immunohistochemistry Protocol:

- Perform antigen retrieval with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 80°C for 30 minutes

- Block endogenous peroxidases with 3% H₂O₂ in methanol for 15 minutes

- Incubate with blocking solution (10% normal goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100) for 2 hours

- Apply primary antibodies: Mouse anti-ERα (1:1000) and Rabbit anti-ERβ (1:2000) in blocking solution for 48 hours at 4°C

- Incubate with biotinylated secondary antibodies (1:500) for 2 hours at room temperature

- Process with ABC elite kit for 90 minutes followed by DAB peroxidase substrate

- Counterstain with thionin, dehydrate, clear, and coverslip

Quantification and Analysis:

- Use stereological counting methods with systematic random sampling

- Employ optical fractionator for unbiased cell counting

- Determine staining intensity via densitometry with image analysis software

- Conduct double immunofluorescence with confocal microscopy for subcellular localization [11]

Protocol: Ovariectomy and Estradiol Replacement in Rodent Models

The ovariectomized (OVX) rat model represents a cornerstone experimental approach for investigating estrogen deficiency and replacement effects on cognitive function and neural mechanisms.

Surgical Procedure:

- Anesthetize female albino rats (150-180g) with ketamine/xylazine (80/10 mg/kg, i.p.)

- Make bilateral dorsal incisions parallel to the spinal column

- Isolate and excise ovaries following vessel cauterization

- For sham operations: expose ovaries without removal

- Administer postoperative analgesia for 72 hours

Estradiol Replacement Protocol:

- For OVX+E2 group: administer 17β-estradiol subcutaneously (1-5 μg/day) dissolved in sesame oil

- For control groups: administer vehicle alone

- Treatment duration typically 4-8 weeks postsurgery

Cognitive and Molecular Assessments:

- Spatial learning and memory testing using Morris Water Maze (4 trials/day for 5 days)

- Neurotransmitter analysis via HPLC in hippocampal and prefrontal tissue

- Serum estradiol, nerve growth factor (NGF), and amyloid precursor protein measurements by ELISA

- Gene expression analysis of Cx43, LRP1, and RAGE using RT-PCR

- Synaptic density evaluation via Postsynaptic Density Protein 95 (PSD-95) immunohistochemistry [7]

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Ovariectomy and Estradiol Replacement Studies. This rodent model examines the effects of estrogen deficiency and replacement on cognitive function and underlying neural mechanisms.

Molecular Signaling Pathways in Cognitive Circuits

Genomic and Non-Genomic Signaling Mechanisms

Estrogen receptors regulate cognitive function through diverse molecular pathways that can be broadly categorized into genomic and non-genomic signaling mechanisms. Genomic signaling involves ER dimerization, binding to estrogen response elements (EREs) in target gene promoters, and recruitment of coregulator complexes to modulate transcription of genes involved in synaptic plasticity, neuroprotection, and metabolism [10]. This classical mechanism underlies many of estrogen's longer-term effects on neuronal structure and function.

In parallel, non-genomic signaling occurs rapidly through membrane-associated ERs that activate intracellular kinase cascades, including MAPK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, and PKC pathways [10]. These rapid signaling events can modulate ion channel activity, neurotransmitter release, and dendritic spine dynamics within minutes, providing a mechanism for estradiol to immediately influence neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission. The integration of these complementary signaling modes allows for precise spatiotemporal control of estrogen actions in hippocampal and prefrontal circuits supporting cognitive function.

Receptor-Specific Signaling and Cross-Talk

ERα and ERβ exhibit both overlapping and distinct signaling properties that contribute to their specialized functions in cognitive circuits. While both receptors can activate common pathways, they also display preferential signaling biases; for instance, ERβ shows particularly strong interactions with metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling and enhances BDNF/CREB pathways implicated in synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation [14]. Additionally, ER signaling exhibits extensive cross-talk with other receptor systems, including dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate receptors, enabling estradiol to fine-tune diverse neurotransmitter systems essential for cognitive performance [10].

The relative balance between ERα and ERβ signaling appears crucial for optimal cognitive function, with evidence suggesting that disruption of this balance contributes to neuropsychiatric symptoms in conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), where reduced ERβ activity relative to ERα dominance has been proposed as a mechanism underlying cognitive and affective disturbances [14]. This receptor interplay represents a promising target for developing selective estrogen receptor modulators with improved therapeutic profiles for cognitive disorders.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Estrogen Receptor Research in Cognitive Circuits

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER Agonists | 17β-estradiol (endogenous), DPN (ERβ-selective) | Receptor-specific activation, cognitive behavioral studies | DPN: 1.0 mg/kg SC for systemic administration; 10 pg IC for BLA infusions |

| ER Antagonists | ICI 182,780 (general ER), PHTPP (ERβ-selective) | Receptor mechanism studies, pathway blockade | Specificity varies; validate with multiple antagonists |

| Antibodies | Mouse anti-ERα, Rabbit anti-ERβ | IHC, Western blot, cellular localization | Challenge with antibody specificity; use multiple validation methods |

| Animal Models | Ovariectomized rats, ER knockout mice | Hormone depletion studies, receptor-specific functions | Consider compensatory mechanisms in knockout models |

| Behavioral Assays | Morris Water Maze, cue-induced reinstatement | Spatial memory, extinction memory recall | Test multiple cognitive domains for comprehensive assessment |

The precise distribution of ERα and ERβ within hippocampal and prefrontal circuits creates a sophisticated regulatory network through which estradiol modulates cognitive performance. The distinct spatial-temporal expression patterns of these receptor subtypes during development and their dynamic regulation throughout the lifespan enable complex cognitive processing while also creating vulnerabilities to hormonal fluctuations. Future research should prioritize the development of more selective pharmacological tools to target specific ER populations in defined brain regions, ultimately enabling more precise therapeutic interventions for cognitive disorders associated with estrogen signaling deficits. The integration of human neuroimaging with molecular approaches in animal models will be essential for translating these fundamental discoveries into clinical applications that preserve and enhance cognitive function across the lifespan, particularly in populations experiencing hormonal transitions.

Estradiol (17β-estradiol), the most bioactive endogenous estrogen, exerts profound influences on the structure and function of the hippocampus, a brain region critical for learning, memory, and stress regulation [15] [16]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the mechanisms by which estradiol modulates hippocampal plasticity, focusing on synaptic formation, dendritic spine dynamics, and neuroprotective pathways. Understanding these hormonal mechanisms is paramount for developing targeted therapies for cognitive aging and neurodegenerative disorders, which display significant sex differences in prevalence and progression [15] [7]. The evidence underscores that estradiol operates through genomic, non-genomic, and neurosteroid pathways to maintain cognitive function, with implications for drug development in conditions involving hippocampal dysfunction [16].

Molecular Mechanisms of Estradiol Action

Estradiol signals through multiple receptor systems to orchestrate its effects on hippocampal plasticity. The classic genomic actions involve estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), which are ligand-dependent transcription factors found in the nucleus and at extranuclear sites within hippocampal neurons [15] [16]. Upon binding, these receptors dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, where they bind to estrogen response elements (EREs) on DNA, initiating gene transcription and protein synthesis that underlie long-lasting structural changes [16]. Additionally, the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1) mediates rapid, non-genomic signaling cascades [15].

Table: Estrogen Receptors in the Hippocampus

| Receptor Type | Primary Location | Signaling Mechanism | Key Functions in Hippocampus |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | Nucleus, Dendrites [15] | Genomic (slow, sustained) [16] | Modulates spine density; influences neurogenesis [15] |

| ERβ | Nucleus, Dendrites [15] | Genomic (slow, sustained) [16] | Contributes to neuroprotection and synaptic plasticity [15] |

| GPER1 | Plasma Membrane [15] | Non-genomic (rapid) [16] | Activates intracellular signaling pathways (e.g., MAPK) [16] |

A more recent paradigm highlights estradiol's role as a neurosteroid, synthesized de novo from cholesterol within hippocampal neurons themselves [16]. This local synthesis allows for rapid modulation of synaptic function and memory consolidation independent of peripheral hormone levels [16]. The signaling pathways activated by estradiol receptor binding, particularly the MAPK and PI3K pathways, are crucial for downstream effects on neuronal growth, survival, and structural plasticity [17].

Figure 1: Estradiol Signaling Pathways in Hippocampal Plasticity. Estradiol (E2) acts via classical genomic signaling through nuclear ERα and ERβ to regulate gene transcription, and via rapid non-genomic signaling through membrane-associated GPER1 to activate kinase pathways. E2 can also be synthesized locally in the hippocampus, acting as a neurosteroid to modulate synaptic function and memory [15] [16].

Structural Plasticity: Dendritic Spines and Synaptic Formation

Dendritic spines are the primary sites of excitatory synaptic input in the hippocampus, and their density and morphology are robustly modulated by estradiol. Fluctuations in circulating estradiol across the estrous cycle in rodents cause dynamic changes in apical CA1 dendritic spine density, with the highest densities (approximately 30% higher) coinciding with phases of high estradiol [15]. Ovariectomy (OVX), which removes the primary source of estrogens, decreases spine density, a effect that can be reversed by exogenous estradiol administration [15] [18].

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Estradiol on Dendritic Spine Density

| Experimental Model | Intervention | Hippocampal Region | Effect on Spine Density | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovariectomized (OVX) Rats | Estradiol Benzoate | CA1 | Increased density, peaking at 2-3 days post-treatment [15] | [15] |

| Dissociated Hippocampal Cultures | 17β-estradiol | Pyramidal Neurons | ~2-fold increase in density [18] | [18] |

| Female Rats Across Estrous Cycle | Natural fluctuation | CA1 | ~30% higher density at proestrus (high E2) vs. low E2 phases [15] | [15] |

The mechanism involves estradiol-mediated decrease in inhibitory tone from GABAergic interneurons, leading to a shift toward enhanced excitation in pyramidal neurons [18]. This excitation drives the activation of cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation, a critical step for the formation of novel dendritic spines [18]. Subsequent to spine formation, estradiol increases the density of glutamatergic receptors and enhances synaptic network activity [18]. The shape of spines is also functionally significant, with estradiol promoting the formation of mature "mushroom" spines, which are stable and support memory, and thin "learning" spines, which are more plastic [15].

Functional Correlates: Cognitive Performance and Neuroprotection

The structural changes induced by estradiol have direct functional consequences for hippocampal-dependent cognition and neuronal resilience.

Cognitive Performance Across the Lifespan

Estradiol modulates various cognitive domains, particularly memory. In animal models, estradiol enhances performance on spatial learning and memory tasks, such as the Morris water maze [7]. In humans, the "critical window" or "timing" hypothesis proposes that estradiol replacement is most beneficial for cognition when initiated close to the time of menopause. Recent large-scale observational studies provide supporting evidence:

- Menopause Age: Earlier age at menopause is associated with lower performance in episodic memory, prospective memory, and executive functions [8] [19].

- Hormone Therapy (HT) Route: The administration route of estradiol-based HT affects different cognitive domains. Transdermal estradiol is associated with higher episodic memory scores, while oral estradiol is linked to better prospective memory [8] [19]. This is potentially because oral estradiol undergoes first-pass hepatic metabolism, converting it to less potent estrone [8].

- Surgical Menopause: Oophorectomy prior to natural menopause is linked to cognitive risk, which can be mitigated by HT initiated around the time of surgery [9].

Table 2: Association of Estradiol-Based Hormone Therapy with Cognitive Domains in Postmenopausal Women

| Cognitive Domain | Key Brain Region | Association with Transdermal E2 | Association with Oral E2 | Evidence Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic Memory | Medial-temporal lobes [8] | Significantly higher scores [8] [19] | Not significant | Class III [8] |

| Prospective Memory | Frontal & Medial-temporal lobes [8] | Not significant | Significantly higher scores [8] [19] | Class III [8] |

| Executive Functions | Frontal lobes [8] | Not significant | Not significant | Class III [8] |

Furthermore, estradiol modulates reward-based learning by influencing dopaminergic signaling in the nucleus accumbens, a region interconnected with the hippocampus. Elevated endogenous estradiol predicts enhanced reward prediction errors and reinforcement learning, linked to reduced expression of dopamine reuptake transporters [20].

Neuroprotective Mechanisms

Estradiol confers neuroprotection through multiple interconnected pathways, countering processes that lead to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration.

- Synaptic Health: Estradiol upregulates key synaptic proteins like Postsynaptic Density Protein 95 (PSD-95), which is crucial for synaptic stability and function. Its deficiency, as in OVX models, leads to reduced PSD-95 and impaired cognition [7].

- Amyloid-β (Aβ) Clearance: Estradiol modulates proteins involved in Aβ trafficking across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). It upregulates Lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), which facilitates Aβ clearance from the brain, and downregulates the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), which mediates Aβ influx into the brain [7].

- Neuroinflammation and Neurotrophic Support: Estradiol deficiency increases pro-inflammatory signaling, which is ameliorated by replacement. It also maintains levels of neurotrophic factors like Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), supporting neuronal survival [7].

- Cellular Communication: Estradiol increases the expression of the gap junction protein connexin-43 (Cx43), thereby enhancing intercellular communication and potentially supporting metabolic coupling and neuronal health [7].

Figure 2: Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Estradiol and Consequences of its Deficiency. Estradiol deficiency leads to a cascade of detrimental events in the hippocampus, including synaptic instability, impaired amyloid-β clearance, neuroinflammation, reduced neurotrophic support, and disrupted cellular communication, collectively increasing the risk for cognitive decline and neurodegeneration [7].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Research on estradiol and hippocampal plasticity relies on well-established in vivo and in vitro models.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ovariectomized (OVX) Rat Model of Menopause [7]

- Purpose: To investigate the effects of estradiol deficiency and replacement on cognitive function and molecular markers.

- Procedure:

- Surgery: Female rats undergo bilateral ovariectomy or a sham operation under anesthesia.

- Recovery & Grouping: Animals are allowed to recover and are then divided into groups (e.g., OVX, OVX + 17β-estradiol treatment, sham control).

- Treatment: 17β-estradiol is administered via subcutaneous injection or other routes for a specified period.

- Cognitive Testing: Spatial learning and memory are assessed using the Morris Water Maze. Rats are trained to find a hidden platform, and metrics like escape latency and time spent in the target quadrant are measured.

- Tissue Collection: Hippocampal tissue and serum are collected for molecular analysis.

- Downstream Analysis:

- ELISA: To quantify serum estrogen, NGF, Aβ, and PSD-95 levels.

- RT-PCR: To measure gene expression of Cx43, LRP1, and RAGE.

- HPLC: To analyze neurotransmitter levels (e.g., acetylcholine, monoamines).

Protocol 2: Primary Hippocampal Neuronal Culture & Dendritic Spine Analysis [18]

- Purpose: To directly visualize and quantify the rapid effects of estradiol on dendritic spine formation and morphology.

- Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Hippocampal pyramidal neurons are dissociated from rat embryos and cultured on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips.

- Treatment: Cultures are treated with 17β-estradiol (e.g., 10 nM) for 24-48 hours. Controls receive vehicle.

- Pharmacological Blockade: To probe mechanisms, cultures can be co-treated with antagonists (e.g., NMDA receptor blockers, ER antagonists) or inhibitors of signaling pathways (e.g., MAPK inhibitors).

- Immunocytochemistry: Neurons are fixed and stained for spine visualization (e.g., using DiI or GFP-actin) and synaptic markers (e.g., synapsin I, PSD-95).

- Downstream Analysis:

- Confocal Microscopy: High-resolution imaging of dendritic segments.

- Image Analysis: Using software to quantify spine density, spine type classification (thin, stubby, mushroom), and synaptic puncta density.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Estradiol's Role in Hippocampal Plasticity

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| 17β-estradiol | The most potent endogenous estrogen; used for replacement studies. | Administered to OVX rodents or added to neuronal cultures to restore estrogenic signaling [7]. |

| OVX Rodent Model | A model for surgical menopause, inducing a state of estradiol deficiency. | Used to study the consequences of estrogen loss and efficacy of replacement therapies [15] [7]. |

| Morris Water Maze | A behavioral apparatus to assess spatial learning and memory. | Tests cognitive function in rodents after OVX and estradiol replacement [7]. |

| ER-specific Agonists/Antagonists | Compounds that selectively activate or block ERα or ERβ. | Used to dissect the specific receptor mediating estradiol's effects in vitro and in vivo [15]. |

| Primary Hippocampal Neuronal Cultures | In vitro system for mechanistic studies. | Allows direct observation of estradiol's effects on spine density and synaptogenesis [18]. |

| Antibodies for PSD-95, Synapsin I | Markers for postsynaptic and presynaptic structures, respectively. | Used in immunohistochemistry or Western blot to quantify synaptic changes [18] [7]. |

| ELISA Kits for NGF, Aβ, PSD-95 | Quantify protein levels in tissue homogenates or serum. | Measures biochemical correlates of neuroprotection and synaptic integrity [7]. |

Estradiol is a pivotal regulator of hippocampal plasticity, exerting its effects through a sophisticated interplay of genomic, non-genomic, and neurosteroid mechanisms. It directly promotes structural changes by increasing dendritic spine density and synaptogenesis, while concurrently enabling functional enhancements in learning, memory, and reinforcement learning. Furthermore, its broad neuroprotective actions safeguard against processes linked to neurodegenerative diseases. Future research and drug development must account for critical variables such as the "critical window" for intervention, the route of administration, and individual risk factors like APOE ε4 status to translate these mechanistic insights into effective, personalized therapies for cognitive decline [8] [19] [9].

Estradiol, the most potent endogenous estrogen, exerts profound neuromodulatory effects critical for cognitive function by interacting with the cholinergic and serotonergic systems. This review synthesizes evidence from preclinical and clinical studies demonstrating that estradiol regulates key neurobiological substrates for learning, memory, and affective processing. Through genomic and non-genomic mechanisms, estradiol enhances cholinergic function in the basal forebrain and modulates serotonergic signaling via regulation of synthesis, transport, and receptor expression. The clinical implications of these interactions are explored, including the differential cognitive effects of hormone therapy formulations and the potential for targeted interventions in cognitive aging and neuropsychiatric conditions. Understanding these complex neurotransmitter interactions provides a foundation for developing precision medicine approaches to maintain brain health in aging women.

Estradiol's role in the brain extends far beyond reproductive functions to encompass complex modulation of neurotransmitter systems integral to cognitive processes. The cholinergic system, particularly vulnerable in age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease, and the serotonergic system, implicated in mood and affective components of cognition, represent two critical targets of estradiol action. This review examines the mechanistic basis for estradiol's interactions with these systems and their collective impact on cognitive performance within the context of hormonal influences on brain health across the lifespan. Understanding these interactions provides crucial insights for developing hormone-based strategies to support cognitive function during reproductive transitions and in later life.

Estradiol-Mediated Modulation of the Cholinergic System

Neurobiological Foundations

The basal forebrain cholinergic system serves as a primary regulator of attention, learning, and memory formation—cognitive domains that display significant sensitivity to estradiol status. Extensive research demonstrates that basal forebrain cholinergic neurons depend on estradiol support for adequate functioning [21] [22]. Estradiol modulates cholinergic neurotransmission through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of:

- High-affinity choline uptake

- Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) activity and mRNA expression

- Nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression

- Acetylcholine release and receptor dynamics

Table 1: Estradiol Effects on Cholinergic Markers in Preclinical Models

| Cholinergic Marker | Effect of Estradiol | Brain Region | Functional consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) | Increases activity & mRNA expression | Basal forebrain, hippocampus | Enhanced acetylcholine synthesis |

| High-affinity choline uptake | Upregulates | Cortex, hippocampus | Increased acetylcholine production |

| Nerve growth factor (NGF) | Increases expression | Basal forebrain | Enhanced cholinergic neuron survival |

| Acetylcholine release | Potentiates | Hippocampus, cortex | Improved synaptic transmission |

Molecular Mechanisms

Estradiol exerts both genomic and non-genomic effects on cholinergic function. Genomic actions involve classical estrogen receptor (ERα and ERβ) binding to estrogen response elements (EREs) in cholinergic gene promoters, modulating transcriptional activity over hours to days. Non-genomic mechanisms include rapid activation of kinase signaling pathways (MAPK, PI3K) within minutes, influencing cholinergic neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity. These mechanisms collectively enhance cholinergic function, particularly in brain regions critical for cognition such as the basal forebrain, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex [21] [22].

The trophic effects of estradiol on cholinergic neurons are particularly relevant to cognitive aging. Loss of p75 neurotrophin receptors (p75NTR) on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons—receptors modulated by estrogen—is associated with early cognitive dysfunction even without evidence of cellular loss [21]. This suggests estradiol plays a permissive role in maintaining cholinergic signaling integrity during aging.

Functional Consequences for Cognition

Estradiol-cholinergic interactions manifest behaviorally in multiple cognitive domains:

- Attentional processes: Partitioning of attentional resources and performance on effort-demanding tasks

- Working memory: Maintenance and manipulation of information over short intervals

- Episodic memory: Formation and retrieval of contextual memories

- Executive function: Inhibition of irrelevant information and cognitive flexibility

Cholinergic antagonism studies in humans demonstrate that estradiol enhances cholinergic-mediated cognitive performance, with estradiol administration attenuating scopolamine-induced deficits in verbal learning, memory, and attention in postmenopausal women [22]. Functional neuroimaging reveals that these behavioral improvements correlate with normalized brain activation patterns in prefrontal and parietal regions during working memory tasks, providing neural correlates for estradiol-cholinergic interactions.

Diagram 1: Estradiol signaling pathways in cholinergic neurons. Estradiol acts through genomic and non-genomic mechanisms to enhance cholinergic function.

Estradiol Regulation of Serotonergic Signaling

Genomic Regulation of Serotonergic Genes

Estradiol exerts sophisticated control over the serotonergic system through coordinated regulation of genes encoding synthetic enzymes, receptors, and transporters. The molecular mechanisms involve both classical estrogen receptor binding to estrogen response elements (EREs) and transcriptional cross-talk through protein-protein interactions with other transcription factors [23].

Table 2: Estradiol Regulation of Serotonergic Gene Expression

| Gene Target | Regulation by Estradiol | Mechanism | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan hydroxylase-2 (TPH2) | Increased expression | ER binding to ERE in promoter | Enhanced serotonin synthesis |

| Serotonin transporter (SERT) | Increased expression | ER binding to ERE in promoter | Increased serotonin reuptake |

| Serotonin-1A receptor (5-HT1A) | Decreased expression | ER tethering to Sp1, C/EBPβ | Altered autoreceptor function |

| Monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) | Decreased expression | ER tethering to AP-1, Sp1 | Reduced serotonin degradation |

| Monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) | Decreased expression | ER binding to ERE in promoter | Reduced serotonin degradation |

The net effect of these coordinated genomic actions is enhanced serotonergic neurotransmission, which may underlie estradiol's mood-stabilizing and antidepressant effects observed in clinical populations [23]. This is particularly relevant during periods of hormonal fluctuation such as the menopausal transition, when declining estradiol levels may contribute to increased vulnerability to depressive symptoms.

Receptor-Specific Mechanisms

Estradiol signals through two nuclear estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) and the membrane-associated G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER1), with receptor distribution and relative abundance influencing serotonergic modulation. ERβ appears particularly important for serotonergic regulation, with high expression in raphe nuclei and limbic regions involved in mood regulation. Additionally, estradiol-induced activation of intracellular signaling pathways (Src/MAPK, PI3K/AKT) modulates serotonin receptor sensitivity and downstream signaling efficacy, providing mechanisms for rapid serotonergic modulation independent of genomic effects [23] [24].

Implications for Affective Cognition

The serotonergic system plays a well-established role in mood regulation, with estradiol's serotonergic effects manifesting in several cognitive-affective domains:

- Emotional memory processing

- Affective bias in decision-making

- Stress responsiveness

- Reward processing

The higher prevalence of depression in women, particularly during periods of hormonal transition (puberty, postpartum, perimenopause), underscores the clinical relevance of estradiol-serotonergic interactions [23]. These periods represent "windows of vulnerability" where serotonergic stability is compromised by fluctuating hormone environments.

Diagram 2: Estradiol regulation of serotonergic gene expression. Estradiol modulates multiple components of serotonin signaling through genomic and non-genomic mechanisms.

Integrative Cognitive Outcomes and Clinical Evidence

Synergistic Effects on Cognitive Domains

The convergent modulation of cholinergic and serotonergic systems by estradiol produces integrated effects on cognitive function that extend beyond the contributions of either system alone. The cholinergic system primarily supports effortful cognitive processes—sustained attention, working memory maintenance, and explicit memory encoding—while the serotonergic system influences affective bias, emotional memory, and cognitive flexibility. Estradiol's simultaneous enhancement of cholinergic function and modulation of serotonergic signaling creates an optimal neurochemical environment for complex cognitive operations requiring integration of cognitive and affective information [21] [23] [24].

Clinical Studies and Hormone Therapy Considerations

Recent clinical evidence demonstrates that the cognitive effects of estradiol-based hormone therapy are domain-specific and formulation-dependent. A large cross-sectional study of 7,251 postmenopausal women from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging found that earlier age at menopause was associated with lower performance across all cognitive domains, highlighting the importance of hormonal timing [25] [26]. Crucially, the study revealed differential cognitive effects based on administration route:

- Transdermal estradiol was associated with better episodic memory (remembering past experiences) compared to no hormone therapy

- Oral estradiol was associated with better prospective memory (remembering to perform future tasks) compared to no hormone therapy

- Neither administration route significantly affected executive functions

These findings underscore that estradiol formulation matters for cognitive outcomes and suggest that first-pass hepatic metabolism of oral estradiol may influence its neurocognitive effects through alterations in bioactive metabolites or protein binding [25] [26].

Individual Difference Factors

The cognitive response to estradiol is modulated by several individual difference factors:

- APOE genotype: APOE ε4 carriers show enhanced sensitivity to both the beneficial effects of estradiol and the cognitive risks associated with early menopause

- Reproductive history: Parity influences cognitive outcomes, with the association between earlier menopause and executive function particularly pronounced in women with four or more children

- Timing of intervention: The "critical period" hypothesis suggests earlier initiation of hormone therapy following menopause produces more favorable cognitive outcomes

These moderating variables highlight the need for personalized approaches when considering estradiol-based interventions for cognitive support.

Experimental Approaches and Research Methods

Cholinergic-Estradiol Interaction Protocols

Investigation of estradiol-cholinergic interactions in humans has employed sophisticated pharmacological challenge designs:

Diagram 3: Experimental design for estradiol-cholinergic interaction studies. This pharmacological fMRI approach examines how estradiol modulates brain response to cholinergic challenge.

Protocol Details:

- Participants: Carefully screened postmenopausal women, typically within early postmenopausal window (3-6 years since final menstrual period)

- Estradiol administration: Transdermal estradiol (100μg/day) or oral estradiol (1-2mg/day) for 2-3 months to achieve stable physiological levels

- Cholinergic challenge: Acute administration of scopolamine (muscarinic antagonist) or mecamylamine (nicotinic antagonist) at standardized doses

- Assessment: Cognitive testing focusing on attention, working memory, and episodic memory domains; functional MRI during working memory tasks (n-back, delayed match-to-sample)

- Controls: Placebo-controlled, crossover designs where participants receive both active drug and placebo in counterbalanced order

This approach allows researchers to determine how estradiol pretreatment modulates behavioral and neural responses to cholinergic disruption, providing a window into estradiol-cholinergic interactions [21] [22].

Serotonergic-Estradiol Research Methods

Investigation of estradiol's serotonergic effects employs complementary approaches:

- Molecular studies: Reporter assays, chromatin immunoprecipitation, and promoter analysis to map ER binding sites on serotonergic genes

- Neurochemical measures: Microdialysis in raphe nuclei and terminal regions to measure serotonin release and turnover

- Receptor imaging: PET imaging with 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A ligands to quantify receptor availability

- Genetic approaches: ERα and ERβ knockout models to dissect receptor-specific contributions

These methods have elucidated how estradiol coordinates serotonergic gene expression through both classical ERE-mediated mechanisms and protein-protein interactions with transcription factors including Sp1, AP-1, C/EBPβ, and NF-κB at promoter regions lacking canonical ERE sequences [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Estradiol-Neurotransmitter Interactions

| Research Tool | Specific Application | Function/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators | ||

| Tamoxifen | Probing ER involvement | Mixed ER agonist/antagonist; crosses BBB |

| Raloxifene | CNS ER modulation | SERM with tissue-specific actions |

| Estrogen Receptor Agonists | ||

| PPT (Propylpyrazoletriol) | ERα-specific actions | Selective ERα agonist |

| DPN (Diarylpropionitrile) | ERβ-specific actions | Selective ERβ agonist |

| G-1 | GPER1-specific signaling | Selective GPER1 agonist |

| Cholinergic Tools | ||

| Scopolamine | Muscarinic receptor blockade | Non-selective muscarinic antagonist |

| Mecamylamine | Nicotinic receptor blockade | Non-competitive nicotinic antagonist |

| Oxotremorine | Muscarinic receptor activation | Muscarinic receptor agonist |

| Serotonergic Agents | ||

| WAY-100635 | 5-HT1A receptor blockade | Selective 5-HT1A antagonist |

| Citalopram | Serotonin reuptake inhibition | SSRI; increases synaptic 5-HT |

| Fenfluramine | Serotonin release | Promotes 5-HT release and blocks reuptake |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | ||

| ERα/ERβ siRNA | Receptor-specific knockdown | Selective receptor silencing |

| ERE-luciferase reporters | ER transcriptional activity | Measures ER-mediated gene expression |

| ChIP assays | ER-DNA interactions | Maps ER binding to target genes |

These research tools enable dissection of estradiol's mechanisms in modulating cholinergic and serotonergic function, from receptor-specific contributions to downstream transcriptional regulation.

Estradiol orchestrates complex interactions with cholinergic and serotonergic systems through complementary genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. The convergence of these neurotransmitter effects supports key cognitive domains vulnerable in aging and neuropsychiatric conditions. Future research should prioritize:

- Development of receptor-specific estradiol analogs that maximize cognitive benefits while minimizing peripheral risks

- Elucidation of critical period windows for hormone interventions to optimize cognitive outcomes

- Examination of how individual difference factors (genetics, reproductive history, health status) modulate treatment response

- Integration of multi-modal imaging with pharmacological challenges to map circuit-level effects of estradiol-neurotransmitter interactions

The evolving understanding of estradiol's neuromodulatory actions continues to inform targeted therapeutic approaches for maintaining cognitive health across the lifespan, particularly during reproductive transitions when women are at increased risk for cognitive decline and mood disturbances. By leveraging the intricate interactions between estradiol and neurotransmitter systems, researchers can develop more effective, personalized strategies for cognitive support in aging populations.

This whitepaper synthesizes functional neuroimaging evidence elucidating the profound impact of 17β-estradiol (E2) on the neural circuitry underlying memory formation. A growing body of research indicates that E2 enhances memory consolidation through coordinated actions in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), brain regions critical for episodic and spatial memory. This review details the experimental protocols and functional imaging methodologies that have uncovered E2-mediated changes in brain activation, functional connectivity, and synaptic plasticity. Framed within the broader thesis of hormonal mechanisms in cognitive performance, this evidence provides a neurobiological foundation for understanding sex differences in cognitive aging and the elevated risk of neurodegenerative disorders in postmenopausal women, offering critical insights for targeted therapeutic development.

The steroid hormone 17β-estradiol (E2) is a potent regulator of non-reproductive brain functions, with profound implications for learning and memory. The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, brain structures densely populated with estrogen receptors, are exquisitely sensitive to E2 fluctuations [27] [28]. Research conducted over the past decade has begun to unravel the molecular and systems-level mechanisms through which E2 modulates cognitive performance, moving beyond a sole focus on the hippocampus to encompass network-level interactions [27] [29].

A pivotal thesis in this field posits that E2 enhances memory consolidation by orchestrating synchronized activity across a network of brain regions, rather than acting on isolated structures. This coordination is particularly evident between the dorsal hippocampus (DH) and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which show E2-induced increases in functional connectivity and dendritic spine density concurrent with improved memory performance [27] [29]. The timing of E2 administration is critical, with effects following a "healthy cell bias" where benefits are most pronounced when treatment coincides with preserved neural architecture [30] [28].

Understanding these mechanisms is clinically urgent. Women are at substantially greater risk for Alzheimer's disease (AD) than men, even after accounting for longer lifespans [27]. The decline in circulating E2 levels during menopause is thought to contribute to this vulnerability, rendering neurons more susceptible to age-related decline [27] [31]. This whitepaper consolidates functional neuroimaging evidence from rodent and human studies to delineate E2-induced changes in hippocampal and prefrontal activation, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to translate these findings into novel cognitive therapeutics.

Estradiol and Memory Consolidation: Core Mechanisms

Molecular Signaling Pathways

E2 enhances memory through rapid, non-genomic signaling and slower, genomic pathways. In the dorsal hippocampus, post-training E2 infusion rapidly activates cell-signaling cascades such as the ERK/MAPK pathway, leading to increased dendritic spine density on CA1 pyramidal neurons within hours [27] [28]. This spinogenesis is temporally aligned with the window for memory consolidation, suggesting a direct structural correlate of E2-mediated memory enhancement.

The canonical estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, as well as the membrane-associated G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), are localized throughout the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex [27]. These receptors can act as nuclear transcription factors and interact with neurotransmitter receptors at the membrane to stimulate intracellular signaling [27]. Hippocampal E2 synthesis occurs de novo independently of ovarian sources, providing localized hormone regulation that influences synaptic plasticity in both sexes [27].

Table 1: Key Molecular Players in E2-Mediated Memory Consolidation

| Molecule/Pathway | Function in E2 Signaling | Effect on Memory |

|---|---|---|

| ERα & ERβ | Classical nuclear receptors; also mediate rapid membrane signaling | Genomic and non-genomic regulation of memory formation [27] |

| GPER | G protein-coupled membrane estrogen receptor | Activates rapid cell-signaling cascades (e.g., ERK) [27] |

| ERK/MAPK Pathway | Key intracellular signaling cascade | Critical for E2-induced spinogenesis and memory consolidation [27] [28] |

| Dendritic Spines | Postsynaptic sites of excitatory connections | Increased density in hippocampal CA1 and mPFC correlates with memory enhancement [29] [28] |

Functional Circuitry: Hippocampus-Prefrontal Cortex Interactions

A paradigm shift in the field recognizes that E2-mediated memory consolidation requires the concurrent activity of multiple brain regions. Chemogenetic inhibition of the mPFC during E2 infusion into the DH completely blocks the enhancing effects of E2 on both object recognition and spatial memory, demonstrating that mPFC activity is obligatory for DH-dependent memory consolidation [29]. This finding indicates a functional circuit where E2 action in one node (the DH) requires the functional integrity of another (the mPFC).

Resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) studies in humans corroborate these circuit-level findings. In postmenopausal women, higher E2 levels are associated with enhanced functional connectivity between the parahippocampal gyrus and the precuneus, a key hub of the default mode network (DMN) [31]. The DMN is implicated in memory and cognitive function, and its modulation by E2 may underlie the hormone's effects on cognitive performance [30].

Diagram Title: E2 Modulates Memory via a Hippocampal-Prefrontal Circuit

Experimental Protocols & Key Findings

Rodent Models: Behavioral Tasks and Intracranial Infusions

Protocol: Object Recognition (OR) and Object Placement (OP) Tasks

- Purpose: To assess nonspatial (OR) and spatial (OP) memory consolidation in rodents. These one-trial tasks capitalize on rodents' innate preference for novelty [29].

- Subjects: Young adult ovariectomized (OVX) female mice or rats to control for endogenous hormone fluctuations.

- Procedure:

- Training: The subject is placed in an arena with two identical objects for a set exploration time (e.g., 30 seconds total).

- Infusion: Immediately post-training, the subject receives a bilateral microinfusion of E2 or vehicle directly into the dorsal hippocampus (DH) or medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).

- Testing:

- OR: Conducted 48 hours post-training. One familiar object is replaced with a novel object. More time spent with the novel object indicates successful memory consolidation.

- OP: Conducted 24 hours post-training. One object is moved to a novel location. More time spent with the moved object indicates intact spatial memory.

- Key Findings: Post-training infusion of E2 into either the DH or mPFC significantly enhances performance on both OR and OP tasks compared to vehicle controls, confirming E2's role in memory consolidation within these structures [29].

Protocol: Chemogenetic Inhibition During E2 Infusion

- Purpose: To test the necessity of concurrent mPFC activity for E2-mediated memory enhancement in the DH.

- Subjects: OVX female mice.

- Procedure:

- Surgery: Bilateral cannulation of the DH for E2 infusion and viral vector injection into the mPFC to express inhibitory DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) in excitatory neurons.

- Behavioral Testing: After recovery, mice undergo OR/OP training.

- Post-Training: Simultaneous infusion of E2 (or vehicle) into the DH and systemic injection of the DREADD ligand CNO (or vehicle) to inhibit mPFC neurons.

- Key Findings: Chemogenetic inhibition of the mPFC completely blocks the memory-enhancing effect of DH E2 infusion. This demonstrates that mPFC activity is required for E2-mediated, DH-dependent memory consolidation [29].

Table 2: Summary of Key Rodent Model Findings

| Experimental Manipulation | Behavioral Outcome (vs. Control) | Neural Correlate |

|---|---|---|

| DH E2 Infusion | Enhanced OR and OP memory [29] | ↑ Spine density in DH CA1 and mPFC [29] |

| mPFC E2 Infusion | Enhanced OR and OP memory [29] | ↑ Spine density in mPFC (apical dendrites) [29] |

| mPFC Inhibition + DH E2 | Blocks memory enhancement [29] | Disrupts functional hippocampal-prefrontal circuit |

Human Studies: Functional Neuroimaging and Hormonal Manipulation

Protocol: Resting-State fMRI in Postmenopausal Women

- Purpose: To examine the relationship between serum E2 levels and functional connectivity in estrogen-sensitive brain regions.

- Subjects: Cognitively healthy postmenopausal women not undergoing hormone therapy.

- Procedure:

- Blood Sampling: Venous blood is drawn on the same day as the MRI scan to assess serum E2 levels via radioimmunoassay.

- MRI Acquisition: High-resolution structural and resting-state BOLD fMRI scans are obtained. Participants are instructed to rest quietly with their eyes open.

- Data Analysis: Functional connectivity is analyzed using ROI-to-ROI approaches in software like CONN or SPM. Key regions of interest (ROIs) include the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), and precuneus.

- Key Findings: Higher E2 levels are associated with enhanced functional connectivity between the parahippocampal gyrus and the precuneus. This suggests E2 modulates connectivity within memory-related networks, even in the resting state [31].

Protocol: Pharmacological fMRI and Cognitive Testing

- Purpose: To investigate the effects of estrogen therapy or estrogen suppression on brain activation during cognitive tasks.

- Subjects: Premenopausal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal women.

- Procedure:

- Hormonal Manipulation: Administration of conjugated equine estrogens, 17β-estradiol, or an aromatase inhibitor (e.g., letrozole) to suppress endogenous E2 synthesis.

- Cognitive Testing During fMRI: Participants perform cognitive tasks (e.g., verbal memory, mental rotation) in the scanner.

- Data Analysis: Brain activation patterns and performance accuracy are compared across treatment groups or correlated with hormone levels.

- Key Findings:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Investigating E2 Effects

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 17β-Estradiol (E2) | The primary experimental estrogen for in vivo and in vitro studies. | Microinfusion into brain regions (DH, mPFC) to study localized effects on memory [29] [28]. |

| Ovariectomized (OVX) Rodent Model | Standardized model for studying E2 in a low-estrogen background. | Base model for all E2 replacement studies; allows control over hormone exposure [29] [28]. |

| DREADD Technology (AAV-CaMKIIα-hM4Di) | Chemogenetic tool for targeted neuronal inhibition. | Testing necessity of mPFC activity in E2-mediated memory consolidation [29]. |

| Clozapine-N-Oxide (CNO) | Inert ligand that activates DREADD receptors. | Administered systemically to inhibit mPFC neurons expressing hM4Di during behavioral testing [29]. |

| Golgi-Cox Staining Kit | Histological method for visualizing neuronal morphology. | Quantifying changes in dendritic spine density in DH and mPFC following E2 administration [29]. |

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kits | Sensitive quantification of hormone levels from serum or tissue. | Measuring circulating E2 levels in human subjects or rodent models [31]. |

| Aromatase Inhibitor (Letrozole) | Suppresses endogenous E2 synthesis by inhibiting the aromatase enzyme. | Modeling E2 deficiency in rodents and studying resulting cognitive and functional connectivity changes [30]. |

Discussion and Future Directions