Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Reproductive Health: Mechanistic Insights, Research Methodologies, and Therapeutic Implications for Infertility and Cancer

This comprehensive review synthesizes current evidence on the impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on infertility and reproductive cancers for researchers and drug development professionals.

Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Reproductive Health: Mechanistic Insights, Research Methodologies, and Therapeutic Implications for Infertility and Cancer

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current evidence on the impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on infertility and reproductive cancers for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational mechanisms by which EDCs like bisphenol A, phthalates, and pesticides disrupt hormonal homeostasis and epigenetic regulation, leading to impaired fertility and carcinogenesis. The article evaluates advanced methodological approaches for studying EDC effects, addresses key challenges in risk assessment including low-dose and mixture effects, and validates findings through comparative analysis of epidemiological and experimental data. By integrating mechanistic insights with clinical implications, this review aims to inform the development of targeted diagnostic biomarkers and novel therapeutic interventions.

Unraveling the Mechanisms: How EDCs Disrupt Reproductive Biology and Promote Carcinogenesis

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a class of exogenous substances that interfere with hormonal signaling pathways, posing a significant threat to global public health. The pervasive presence of these chemicals in modern environments has coincided with concerning trends in reproductive health and hormone-sensitive cancers. This whitepaper synthesizes current epidemiological evidence and mechanistic insights linking EDC exposure with rising rates of infertility and hormone-sensitive cancers, particularly breast and ovarian malignancies. Within the broader thesis on EDC impacts, this analysis demonstrates how these chemicals create a dual burden on reproductive and oncological health through shared molecular pathways, highlighting an urgent need for targeted research and evidence-based regulatory interventions.

Epidemiological Evidence: Quantitative Associations Between EDCs and Disease Outcomes

Global Trends in Female Infertility and EDC Exposure

Table 1: Association Between EDC Metabolites and Female Infertility (NHANES 2001-2006) [1]

| EDC Metabolite Category | Specific EDCs | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval | Study Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phthalates | DnBP | 2.10 | 1.59–2.48 | 3,982 women (463 infertile) |

| Phthalates | DEHP | 1.36 | 1.05–1.79 | 3,982 women (463 infertile) |

| Phthalates | DiNP | 1.62 | 1.31–1.97 | 3,982 women (463 infertile) |

| Phthalates | DEHTP | 1.43 | 1.22–1.78 | 3,982 women (463 infertile) |

| Phthalates | PAEs | 1.43 | 1.26–1.75 | 3,982 women (463 infertile) |

| Phytoestrogens | Equol | 1.41 | 1.17–2.35 | 3,982 women (463 infertile) |

| PFAS | PFOA | 1.34 | 1.15–2.67 | 3,982 women (463 infertile) |

| PFAS | PFUA | 1.58 | 1.08–2.03 | 3,982 women (463 infertile) |

A large-scale cross-sectional study utilizing the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database demonstrated significant associations between multiple EDC metabolites and female infertility. The research encompassed 3,982 reproductive-age women, including 463 with infertility, and revealed that increased exposure to various EDCs substantially elevated infertility risk. Subgroup analyses further indicated that advanced age and elevated body mass index may exacerbate susceptibility to EDC-related infertility, suggesting potential synergistic effects between metabolic factors and chemical exposures [1].

The global decline in fertility rates parallels increasing environmental EDC contamination. Recent analyses indicate that female reproductive disorders have risen significantly over the past five decades, with EDC exposure identified as a contributing factor. Specific trends include earlier pubertal onset, with modern girls entering breast development and menarche substantially earlier than previous generations, potentially increasing lifelong susceptibility to hormone-sensitive conditions [2].

EDCs and Hormone-Sensitive Cancers: Incidence Patterns

Table 2: EDC Associations with Female-Specific Cancers and Reproductive Outcomes [3] [4] [5]

| Health Outcome | Associated EDCs | Effect Size/Risk Increase | Evidence Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early-onset Breast Cancer | PCBs, PFAS, BPXs, Phthalates, Dioxins | Rising incidence in specific geographic clusters | Observational Studies |

| Ovarian Cancer | Infertility alone (no drugs) | OR: 1.35 (95% CI: 0.92–1.97) | Meta-analysis (25 studies) |

| Ovarian Cancer | Infertility drug use | OR: 1.93 (95% CI: 0.94–2.46) | Meta-analysis (25 studies) |

| Borderline Ovarian Tumors | IVF, clomiphene, human menopausal gonadotropin | OR: 1.87 (95% CI: 1.18–2.97) | Umbrella Meta-analysis |

| Premature Menopause | Pesticides, phthalates | 1.9–3.8 years earlier onset | Epidemiological Review |

| Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) | Organochlorines, PFAS | Up to 20% prevalence in high-exposure regions | Epidemiological Studies |

Recent decades have witnessed a concerning rise in hormone-sensitive breast cancers, particularly estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) phenotypes, with an alarming increase in early-onset cases occurring in women under 50 without family history. Traditional risk factors including genetic predisposition, reproductive history, and lifestyle factors cannot fully explain these epidemiological shifts, suggesting environmental contributions [4].

Geospatial analyses reveal striking patterns in cancer distribution. Early-onset breast cancer incidence shows significant geographic disparities across the United States, with the Northeast region exhibiting the highest absolute incidence rates and significant upward trends over time. These high-incidence regions demonstrate striking overlap with areas characterized by industrial legacy pollution, PFAS contamination, and urban density. The geographic distribution of EPA Superfund sites, contaminated with PCBs, dioxins, and heavy metals, closely mirrors the geographical incidence patterns of early-onset breast cancers [4].

Mechanistic Insights: EDC Disruption of Reproductive and Oncological Pathways

Molecular Mechanisms of Endocrine Disruption

EDCs employ diverse mechanisms to disrupt physiological hormone function. The Endocrine Society has delineated ten key characteristics (KCs) of EDCs, including their ability to: (KC1) interact with or activate hormone receptors; (KC2) antagonize hormone receptors; (KC3) alter hormone receptor expression; (KC4) alter signal transduction in hormone-responsive cells; (KC5) induce epigenetic modifications; (KC6) alter hormone synthesis; (KC7) alter hormone transport; (KC8) alter hormone distribution or circulating levels; (KC9) alter hormone metabolism or clearance; and (KC10) alter the fate of hormone-producing or hormone-responsive cells [3].

These disruptions exhibit complex dose-response relationships. Unlike traditional toxicants, EDCs can produce biphasic or non-monotonic dose-response curves (NMDRs), where effects may not occur at the highest concentrations but manifest at lower exposure levels. This nonlinearity complicates risk assessment and establishes that adverse effects may occur at exposures below currently accepted thresholds [3].

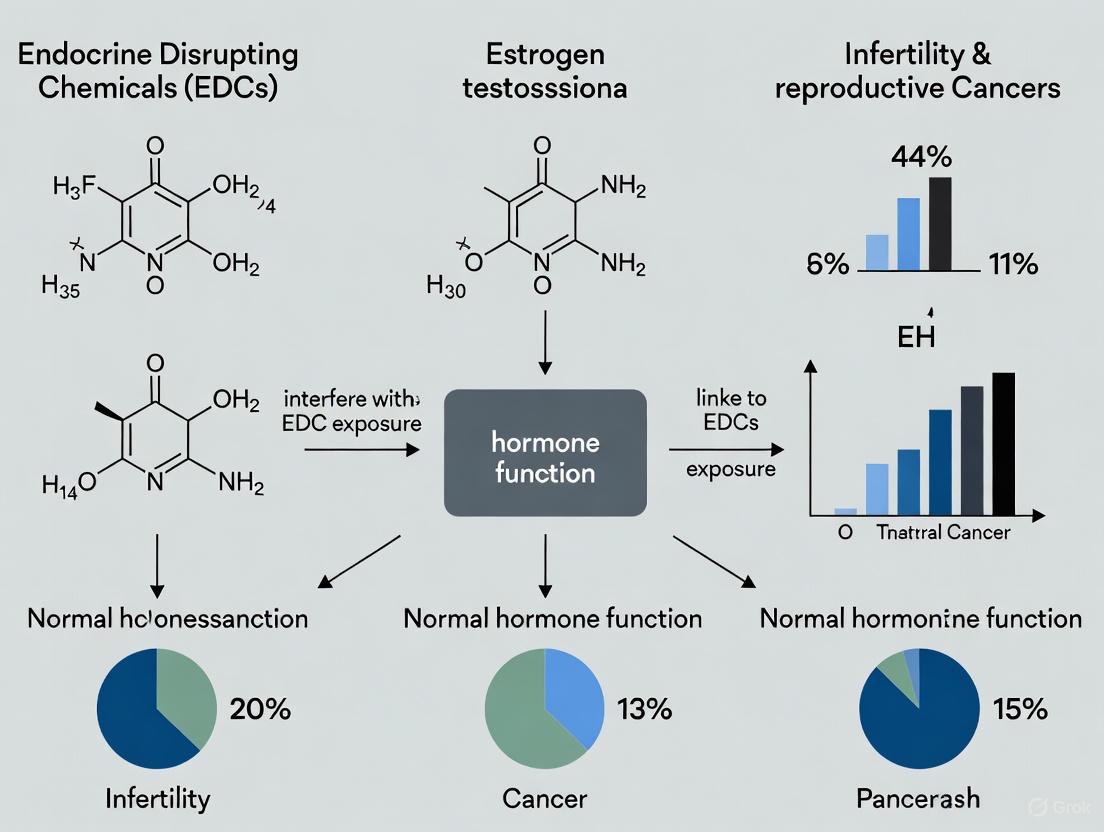

Figure 1: Integrated Pathways of EDC-Mediated Infertility and Carcinogenesis

Tissue Aging and Field Cancerization

Emerging research suggests EDCs function as accelerators of hormone-mediated tissue aging. The breast exhibits a unique aging trajectory dictated not by chronological age but by cumulative hormonal exposure. Each menstrual cycle, pregnancy, lactation period, and menopause timing contributes to hormone-driven cell proliferation, genomic stress, and epigenetic alterations. EDCs amplify this natural process by increasing cumulative hormonal load, potentially explaining the rising incidence of hormone-sensitive breast cancers among younger women [4].

The concept of "field cancerization" describes how EDC exposure remodels tissue biology before malignancy emerges. Chronic EDC exposure during developmentally susceptible windows (in utero, postnatal, peri-pubertal) can reprogram the breast epigenome, accelerate tissue-specific aging, and impair immunosurveillance mechanisms. This creates a permissive microenvironment for carcinogenesis and may explain the increasing early-onset breast cancer incidence without associated family history or genetic predisposition [4].

Methodological Approaches in EDC Research

Epidemiological Study Designs and Exposure Assessment

Table 3: Key Methodological Approaches in EDC Research [1] [6] [7]

| Method Category | Specific Approach | Application in EDC Research | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Designs | Cross-sectional (NHANES) | Population-level association studies | Snapshot in time, cannot establish causality |

| Cohort Studies | Longitudinal follow-up for disease incidence | Time-consuming, expensive, suitable for cumulative effects | |

| Case-Control | Compare exposure histories in cases vs controls | Susceptible to recall bias, efficient for rare outcomes | |

| Exposure Assessment | Biomonitoring (blood, urine) | Direct measurement of EDCs/metabolites | Captures recent exposure for non-persistent EDCs |

| Silicone Wristbands | Personal passive samplers for airborne EDCs | Non-invasive, captures diverse EDC classes | |

| Environmental Sampling | Air, water, dust, food contamination | Source identification, exposure route characterization | |

| Statistical Methods | Multivariate Logistic Regression | Odds ratio calculation with covariate adjustment | Controls confounding, requires careful variable selection |

| Mixture Analysis | Assess combined effects of multiple EDCs | Complex modeling, accounts for real-world exposure | |

| Subgroup Stratification | Identify vulnerable subpopulations | Reveals effect modifiers (age, BMI, ethnicity) |

Research methodologies for investigating EDC impacts have evolved to address the complexity of real-world exposure scenarios. The NHANES-based infertility study employed rigorous multivariate logistic regression adjusted for demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and health-related variables including age, BMI, race, educational attainment, household income, marital status, menstrual history, smoking status, alcohol use, and history of pelvic infections, metabolic syndrome, or viral hepatitis. Sensitivity analyses excluded participants with EDC concentrations above the 99th percentile to evaluate the impact of potential outliers, confirming the robustness of the primary findings [1].

Exposure assessment technologies continue to advance. Silicone wristbands deployed as personal passive samplers have demonstrated detectable levels of EDCs across various chemical classes in nearly all samples, with organophosphate esters (OPEs) and phthalates present in 100% of samples. Crucially, extracts from these wristbands demonstrated hormonal activity in human receptor cell assays, confirming their utility in assessing biologically relevant exposures [4].

Experimental Models and Mechanistic Investigations

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for EDC Research Methodology

Experimental approaches to elucidate EDC mechanisms include in vitro receptor binding assays, animal exposure models, and ex vivo tissue culture systems. These methodologies have demonstrated that EDCs can initiate or exacerbate cancer risks by disrupting hormone signaling and causing DNA damage. Animal studies consistently show that EDC exposure during critical developmental windows produces long-term reproductive consequences, including reduced ovarian reserve, abnormal folliculogenesis, and neuroendocrine control disruption of ovulation [4] [2].

Mechanistic investigations have revealed that persistent EDCs such as PCBs, DDT, PBDEs, organochlorine pesticides, and dioxins resist metabolic degradation and bioaccumulate in lipophilic tissues like breast fat depots. There they can remain for years or even decades, slowly releasing over time and creating prolonged endocrine disruption. Even banned substances like PCBs and DDT persist in the environment and human tissues 20-50 years after regulatory action, highlighting the persistent nature of this public health challenge [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for EDC Investigation [1] [3] [4]

| Research Tool Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Assessment | Silicone wristbands | Personal airborne EDC exposure monitoring | Passive sampling of volatile/semi-volatile EDCs |

| LC-MS/MS standards | Quantification of EDC metabolites | Analytical reference materials for biomonitoring | |

| Antibody-based kits (ELISA) | High-throughput EDC screening | Immunoassay detection of specific EDC classes | |

| Mechanistic Studies | Reporter gene assays (ERα, ERβ, AR) | Receptor activation profiling | Assessment of endocrine receptor pathway disruption |

| Epigenetic analysis kits | DNA methylation/histone modification | Detection of EDC-induced epigenetic alterations | |

| Primary cell cultures (ovarian granulosa, breast epithelium) | Tissue-specific response assessment | Ex vivo modeling of EDC effects on target tissues | |

| Statistical Analysis | R software with mgcv, glmmTMB | Mixture analysis and nonlinear modeling | Advanced statistical packages for complex EDC data |

| Mediation analysis macros | Pathway analysis of EDC effects | Statistical decomposition of direct/indirect effects | |

| Multiple imputation software | Handling values below detection limits | Robust approaches for left-censored exposure data |

The development of validated survey instruments represents another methodological approach to EDC research. Recent work has established reproducible questionnaires assessing reproductive health behaviors aimed at reducing EDC exposure through major routes (food, respiration, dermal absorption). Such tools enable researchers to investigate modifiable protective factors and intervention strategies across diverse populations [7].

Advanced statistical approaches for complex EDC mixture analysis continue to evolve. Methods including weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression, Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR), and latent variable analysis enable researchers to address the challenge of evaluating combined effects of multiple EDCs, better reflecting real-world exposure scenarios where humans encounter complex chemical mixtures rather than single compounds [6].

Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Directions

Despite substantial progress, significant knowledge gaps persist in EDC research. Current evidence relies heavily on observational studies, which face challenges related to confounding, reverse causation, and exposure misclassification. Most human studies cannot definitively establish causality between EDC exposure and disease manifestation, highlighting the need for innovative study designs that strengthen causal inference [6] [2].

Critical research priorities include better characterization of the effects of chronic low-dose EDC exposure throughout the lifespan, particularly during developmentally vulnerable windows. The potential for transgenerational effects remains inadequately explored, as does the impact of real-world chemical mixtures (the "cocktail effect"). Future studies should also focus on identifying susceptible subpopulations through advanced stratification approaches incorporating genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic biomarkers [6] [4] [2].

From a methodological perspective, developing standardized protocols for EDC assessment across matrices and establishing consensus on biomarkers of effect represent urgent needs. The integration of novel exposure assessment technologies with high-resolution health outcomes data in diverse populations will strengthen the evidence base needed to inform regulatory decision-making and public health protection [7] [2].

The accumulating epidemiological and mechanistic evidence firmly establishes EDCs as significant contributors to global trends in infertility and hormone-sensitive cancers. These chemical stressors disrupt delicate endocrine signaling through multiple pathways, with particular potency during developmental windows of susceptibility. The overlapping mechanisms underlying EDC-induced reproductive dysfunction and carcinogenesis highlight the interconnected nature of these health endpoints and suggest potential shared intervention points.

Future research addressing critical knowledge gaps—particularly regarding cumulative mixture effects, vulnerable populations, and transgenerational impacts—will strengthen the scientific foundation for evidence-based policy. As the global burden of infertility and hormone-sensitive cancers continues to rise, translational research integrating epidemiological observations with mechanistic insights offers the greatest promise for developing effective prevention strategies and mitigating the public health impact of these pervasive environmental contaminants.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a significant threat to human reproductive health, with growing evidence linking their exposure to rising rates of infertility and reproductive cancers. These synthetic and naturally occurring substances interfere with normal hormonal signaling pathways, predominantly through receptor-mediated mechanisms that disrupt the delicate balance of estrogenic and androgenic systems. The molecular interplay between EDCs and hormonal receptors has become a critical focus in reproductive toxicology and carcinogenesis research, providing insights into the pathogenic mechanisms underlying chemical-induced reproductive pathologies. This technical guide examines the precise molecular pathways through which EDCs disrupt estrogen and androgen signaling, with particular emphasis on implications for infertility and reproductive cancers research.

Molecular Mechanisms of Disruption

EDCs interfere with estrogen and androgen signaling through multiple interconnected mechanisms at the cellular level, primarily by mimicking or blocking endogenous hormones and altering receptor function.

Nuclear Receptor Interactions

The most extensively characterized mechanism involves direct interaction with nuclear hormone receptors. Bisphenols and phthalates demonstrate potent estrogenic agonist activity through transactivation via dimerization of both estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ). Simultaneously, these compounds exhibit androgenic antagonist activity by inhibiting dihydrotestosterone-induced transactivation through interference with androgen receptor (AR) dimerization [8]. This dual disruption creates profound imbalances in hormonal signaling critical for reproductive function.

Mechanistic Insights: At the molecular level, estrogenic EDCs compete with endogenous estradiol for binding to estrogen receptors, with their binding affinity and subsequent receptor activation potency determining the magnitude of disruption. Molecular initiating events include receptor-ligand binding, receptor dimerization, and recruitment of co-activators or co-repressors to hormone response elements on DNA [8]. The integrated assessment of these events through dimerization and transactivation assays provides a comprehensive understanding of the disruptive potential across different EDC classes.

Non-Monotonic Dose Responses

EDCs frequently exhibit non-monotonic dose-response curves (NMDRs), characterized by U-shaped or inverted U-shaped patterns rather than traditional linear dose-response relationships. This phenomenon occurs because EDCs interact with hormones and activate their receptors in a nonlinear fashion, creating complex dose-response dynamics that challenge conventional toxicological risk assessment [9]. The implications for infertility research are substantial, as low-dose exposures may produce more significant biological effects than higher concentrations, particularly during critical developmental windows.

Epigenetic Modifications

Beyond direct receptor interactions, EDCs induce heritable epigenetic modifications that can persist across generations. These include alterations in DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications, and microRNA expression that regulate gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence [10] [9]. The transgenerational inheritance of EDC-induced reproductive dysfunction represents a particularly concerning mechanism, with demonstrated effects on sperm quality, ovarian function, and reproductive organ development across multiple generations in animal models [10].

Quantitative Analysis of EDC Activities

The endocrine-disrupting properties of various chemical classes have been systematically quantified through integrated assessment approaches combining receptor dimerization and transactivation assays. The following tables summarize key quantitative data relevant to reproductive health research.

Table 1: Estrogenic and Androgenic Disruption Potencies of Common EDCs [8]

| Chemical Class | Specific Compound | ERα-Mediated Agonism | ERβ-Mediated Agonism | AR Antagonism | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenols | BPA | +++ | +++ | +++ | Potent estrogenic agonist and anti-androgenic activity |

| BPS | ++ | ++ | ++ | Similar activity to BPA despite being a "substitute" | |

| BPF | ++ | ++ | ++ | Comparable disruptive profile to BPA | |

| Phthalates | DEHP | + | + | + | Demonstrates estrogenic activity and weak anti-androgenicity |

| DBP | + | + | - | Primarily estrogenic activity without significant AR antagonism | |

| BBP | + | + | + | Dual estrogenic and anti-androgenic properties | |

| Biocides | Vinclozolin | - | - | ++ | Primarily anti-androgenic through AR dimerization interference |

| p,p'-DDE | - | - | + | Weak AR dimerization mediation at high concentrations |

Table 2: Environmental Persistence and Exposure Limits of Reproductive Toxicants [10]

| Category | Substance | Environmental Persistence/Exposure | Mechanism of Reproductive Damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals | Cadmium | Biological half-life: 20-30 years | Compromises blood-testis barrier; impairs sperm quality |

| Lead | Blood levels >10 μg/dL cause sperm DNA damage | Seminal accumulation (3.2 ± 0.8 μg/dL); sperm DNA damage | |

| Arsenic | Occupational exposure >0.01 mg/m³ disrupts testosterone | Metabolite DMA disrupts testosterone biosynthesis | |

| Plasticizers | Bisphenol A (BPA) | Tolerable daily intake: 50 μg/kg (US EPA) | High-affinity binding to estrogen receptors; hormonal imbalance |

| Phthalates (DEHP) | Detected in seminal plasma (0.77-1.85 μg/mL) | Reduced sperm concentration and motility | |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants | PCBs | Half-lives: 8-15 years; lipophilicity (BCF >10⁵) | Adipose tissue accumulation; sustained reproductive system effects |

| Dioxins (PCDD/Fs) | Extreme toxicity (TEF: 0.0001-1) | Severe disruption of androgen synthesis; compromised sperm development |

Table 3: Mixture Effects of Bisphenol Derivatives on Estrogen and Androgen Receptors [8]

| Chemical Combination | Effect on ER Activity | Effect on AR Activity | Implications for Risk Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPA + BPS | Additive estrogenic activity | Enhanced anti-androgenic activity | Mixtures exhibit enhanced disruption compared to individual compounds |

| BPA + BPF | Synergistic at low concentrations | Additive antagonism | Non-additive effects challenge current risk assessment models |

| Multiple phthalate combination | Potentiated estrogenic response | Variable anti-androgenic effects | Real-world exposure scenarios involve complex mixtures |

| Bisphenols + phthalates | Integrated disruptive potential | Combined receptor interference | Cumulative effects on reproductive health parameters |

Experimental Methodologies

Integrated Assessment Approach

The comprehensive evaluation of estrogenic and androgenic endocrine-disrupting properties requires an integrated methodology combining multiple assay systems to capture the full spectrum of disruptive mechanisms.

BRET-Based Receptor Dimerization Assays: Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) technology enables real-time monitoring of receptor homodimerization (ERα, ERβ, and AR) in live cells. Test compounds are prepared as concentrated stock solutions in DMSO according to OECD Test Guideline No. 455 recommendations [8]. Cells expressing receptor fusion constructs (typically luciferase and fluorescent protein tags) are exposed to serial dilutions of EDCs, and dimerization is quantified by BRET signal following ligand addition. This approach directly measures the molecular initiating event of receptor dimerization, providing mechanistic insight into disruptive patterns.

Stably Transf Transcriptional Activation Assays: These assays measure downstream transcriptional activity following receptor activation. Cell lines (e.g., human breast cancer cells for ER, prostate cancer cells for AR) stably transfected with reporter constructs (e.g., luciferase under control of estrogen or androgen response elements) are exposed to EDCs alone (for agonist activity) or in combination with reference agonists (for antagonist activity). Following incubation (typically 16-24 hours), reporter gene activity is quantified, normalized to cell viability, and expressed relative to reference compound responses [8].

Kinetic Signaling Analysis: Time-course signaling data are analyzed using general time course equations and mechanistic model equations. Four primary curve shapes are observed: straight line, association exponential curve, rise-and-fall to zero, and rise-and-fall to steady-state [11]. The initial rate of signaling is quantified by curve-fitting to the whole time course, avoiding selection bias of the linear phase. This approach yields kτ, defining efficacy as the rate of signal generation before regulation mechanisms impact it [11].

Data Analysis Framework

Quantitative analysis of time course data utilizes curve-fitting to estimate kinetic pharmacological parameters. The four characteristic curve shapes are analyzed using corresponding equations:

- Straight line: Response = a × t

- Association exponential: Response = Plateau × (1 - e^(-K × t))

- Rise-and-fall to baseline: Response = (a/(K - k)) × (e^(-k × t) - e^(-K × t))

- Rise-and-fall to steady-state: Response = a × (e^(-k × t) - e^(-K × t)) + c [11]

This analytical framework enables quantification of signaling efficacy as the initial rate of signaling by agonist-occupied receptor (kτ), providing a biologically meaningful metric of signal transduction kinetics before regulation mechanisms introduce complexity.

Pathway Visualization

Figure 1: Molecular Pathway of Estrogenic Signaling Disruption by EDCs. EDCs mimic endogenous estrogens, binding to and activating estrogen receptors, triggering dimerization, coactivator recruitment, and altered gene transcription through estrogen response elements (EREs).

Figure 2: Molecular Pathway of Androgenic Signaling Disruption by EDCs. EDCs act as antagonists by competing with endogenous androgens like DHT, impairing receptor dimerization, promoting corepressor recruitment, and disrupting normal androgen-responsive gene transcription.

Figure 3: Integrated Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive EDC Assessment. The methodology combines dimerization assays, transactivation studies, and kinetic analysis within the Adverse Outcome Pathway framework for mechanistic risk assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for EDC Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Function in EDC Research |

|---|---|---|

| BRET-based dimerization assay systems | Receptor dimerization studies | Quantifies direct receptor-receptor interaction following EDC exposure |

| ERα/ERβ/AR transcriptional activation cell lines | Transactivation potential | Measures downstream gene expression changes from EDC-receptor interaction |

| MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) | Estrogenic activity screening | Endogenous ER expression; sensitive to estrogenic EDCs |

| MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative breast cancer) | Specific ER subtype studies | Useful for transfected receptor studies with minimal background |

| LNCaP (human prostate adenocarcinoma) | Androgenic disruption studies | Endogenous AR expression; responsive to anti-androgenic EDCs |

| CV-1 (monkey kidney fibroblast) | Transfected receptor studies | Low endogenous receptor background for clean transfection results |

| OECD reference compounds (17β-estradiol, DHT) | Assay standardization and validation | Provides benchmark responses for quantifying EDC potency |

| Li+ chloride solution | Response degradation blockade | Inhibits inositol phosphate breakdown in second messenger assays |

| Colorimetric/fluorimetric reporter gene substrates | Transactivation readout | Quantifies transcriptional activity (luciferase, SEAP, β-galactosidase) |

Implications for Reproductive Health Research

The molecular pathways of estrogenic and androgenic disruption have direct implications for understanding and addressing infertility and reproductive cancers. The receptor-mediated mechanisms described herein provide mechanistic links between EDC exposure and adverse reproductive outcomes.

In the context of infertility research, the dual disruption of both estrogen and androgen signaling explains clinical observations of reduced sperm quality, impaired oocyte maturation, and endometrial receptivity issues [10] [12]. The quantitative data on receptor activities directly correlates with epidemiological findings of declining sperm counts and increased female reproductive pathologies. Furthermore, the epigenetic modifications induced by EDC exposure provide a plausible mechanism for the transgenerational inheritance of reproductive dysfunction observed in both animal studies and human populations [9].

For reproductive cancers research, the continuous receptor activation by estrogenic EDCs and simultaneous inhibition of protective androgenic signaling creates a microenvironment conducive to cellular transformation and proliferation. The kinetic parameters of signaling disruption, particularly sustained receptor activation, mirror mechanisms employed by known carcinogens in breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer pathogenesis. The mixture effects documented in quantitative assessments reflect real-world exposure scenarios that may contribute to the increasing incidence of hormone-sensitive reproductive cancers.

The experimental methodologies and research reagents detailed in this guide provide researchers with standardized approaches for identifying and characterizing novel EDCs, screening compound libraries for endocrine activity, and developing targeted interventions to mitigate receptor-mediated disruption in susceptible populations.

Epigenetic reprogramming refers to the comprehensive erasure and re-establishment of epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, during critical developmental periods such as gametogenesis and early embryogenesis [13]. This process plays a fundamental role in regulating gene expression patterns without altering the underlying DNA sequence, serving as a key interface between environmental exposures and genomic function. Within the context of reproductive health, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a significant class of environmental exposures that can interfere with these precise epigenetic reprogramming events [14] [15]. EDCs are synthetic or natural chemicals that mimic, block, or interfere with the body's hormones, including bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, pesticides, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) [16] [15]. A growing body of evidence indicates that exposure to EDCs, particularly during vulnerable developmental windows, can induce persistent alterations in epigenetic regulation, which in turn contribute to the pathogenesis of infertility and reproductive cancers through disrupted gene expression networks [17] [15]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the core mechanisms of epigenetic reprogramming, with a specific focus on how EDC-induced disruptions manifest in transgenerational effects that impact reproductive physiology across generations.

Core Mechanisms of Epigenetic Regulation

DNA Methylation Dynamics

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine residues, primarily within CpG dinucleotides, catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [18] [13]. This epigenetic mark is dynamically regulated throughout development and plays crucial roles in genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and transcriptional regulation.

- Molecular Machinery: The DNMT family includes maintenance methyltransferase DNMT1, which preserves methylation patterns during DNA replication, and de novo methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B, which establish new methylation patterns during development [13]. DNMT3L, a catalytically inactive cofactor, enhances the activity of DNMT3A/B. Conversely, the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family enzymes catalyze DNA demethylation through iterative oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [13].

- Reprogramming During Germ Cell Development: The mammalian genome undergoes two waves of epigenetic reprogramming—during primordial germ cell (PGC) development and preimplantation embryogenesis [13]. In mouse PGCs, genome-wide DNA demethylation reduces 5mC levels to approximately 16.3% by embryonic day E13.5, erasing most methylation marks, including those at imprinted loci [13]. De novo methylation is subsequently established from E13.5 to E16.5, with completion by birth. Human PGCs follow a similar pattern, reaching minimal DNA methylation by weeks 10-11 of gestation [13].

Table 1: DNA Methyltransferases and Their Functions in Mammalian Systems

| Enzyme | Type | Primary Function | Consequences of Dysfunction |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance | Maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication; prefers hemimethylated DNA [13] | Global hypomethylation, genomic instability, spermatogenesis failure [13] |

| DNMT3A | De novo | Establishes new methylation patterns during gametogenesis and embryogenesis [13] | Embryonic lethality (in mice), imprinting disorders, aberrant methylation in spermatogonia [13] |

| DNMT3B | De novo | Works with DNMT3A to establish methylation patterns; targets specific genomic repeats [13] | ICF syndrome, centromeric instability, reduced in round spermatid arrest [13] |

| DNMT3L | Cofactor | Enhances DNMT3A/B binding and activity; essential for establishing genomic imprints [13] | Imprinting defects, impaired spermatogenesis [13] |

Histone Modifications and Chromatin Remodeling

Histone post-translational modifications represent another fundamental layer of epigenetic regulation that controls chromatin accessibility and gene expression. These modifications include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination of specific histone residues [18] [13].

- Regulatory Complexes: Histone-modifying enzymes include histone acetyltransferases (HATs), histone deacetylases (HDACs), histone methyltransferases (HMTs), and histone demethylases (KDMs) [18]. Chromatin remodeling complexes (CRCs) such as SWI/SNF utilize ATP to nucleosomally reposition, eject, or restructure nucleosomes [13].

- Critical Roles in Spermatogenesis: The transition from histones to protamines during spermiogenesis requires extensive histone modification [13]. For example, the histone methyltransferase PRMT5 catalyzes H3R8me2 and H4R3me2, and its deficiency leads to increased H3K9me2 and H3K27me2 levels, altering the chromatin state of PLZF—a critical transcription factor for spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) self-renewal—resulting in SSC developmental defects [13]. Similarly, Suv39h null mice exhibit spermatogenic failure with nonhomologous chromosome associations [13].

Table 2: Key Histone-Modifying Enzymes in Reproductive Tissue Function

| Enzyme/Complex | Modification Catalyzed | Function in Reproduction | EDC-Induced Alterations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIRT1 | Deacetylation | Regulates mitochondrial homeostasis, telomere function [18] | Dysregulated in aging; targeted by pharmacological interventions [18] |

| EZH2 | H3K27me3 | Polycomb repression; stem cell maintenance [18] | Participates in core aging pathways; aberrant expression in reproductive cancers [18] |

| PRMT5 | H4R3me2, H3R8me2 | SSC fate determination; regulates PLZF accessibility [13] | Deficiency alters chromatin state, leading to SSC defects and spermatogenesis disorder [13] |

| Suv39h | H3K9me3 | Heterochromatin formation; chromosome segregation [13] | Null mice show spermatogenic failure with nonhomologous chromosome associations [13] |

Figure 1: EDC Impact on Epigenetic Regulation and Reproductive Health. This diagram illustrates the pathway from EDC exposure through epigenetic disruptions to adverse reproductive outcomes, highlighting key molecular mechanisms.

Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance occurs when environmental exposures induce epigenetic alterations in germ cells that persist across multiple generations, potentially affecting the health of unexposed descendants [19] [20]. This phenomenon represents a significant challenge for risk assessment, as the effects of exposures may not be apparent until subsequent generations.

Mechanisms of Transgenerational Transmission

The transmission of epigenetic information across generations involves several interconnected mechanisms that can operate simultaneously or sequentially:

- DNA Methylation Patterns: Despite global epigenetic reprogramming in PGCs, certain genomic regions, including imprinted genes and specific repetitive elements, can escape erasure and maintain their methylation states [20]. For example, maternal exposure to vinclozolin during pregnancy in rats alters DNA methylation patterns in the sperm of male offspring for at least four generations, associated with increased rates of reproductive abnormalities [19].

- Histone Modifications in Germ Cells: In sperm, retained histones (approximately 1-10% in mammals) carry modifications such as H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 that can potentially influence embryonic development [20]. Disruption of histone methylation in developing sperm, as demonstrated by Siklenka et al. (2015), can impair offspring health transgenerationally [20].

- Non-Coding RNAs: Sperm-borne transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs) and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), can serve as vectors of epigenetic information [20] [21]. For instance, trauma-induced changes in sperm miRNA profiles in mice can alter stress responses in subsequent generations [21].

EDCs and Transgenerational Inheritance of Reproductive Defects

Evidence from animal models provides compelling evidence for EDC-induced transgenerational inheritance of reproductive defects:

- Vinclozolin Exposure: Pregnant rats exposed to the fungicide vinclozolin produce male offspring with increased spermatogenic apoptosis and decreased sperm motility and concentration. These effects persist transgenerationally (F1-F4) and are associated with differential DNA methylation regions (DMRs) in sperm [19].

- BPA and Phthalates: Exposure to BPA and phthalates during critical windows of development can induce transgenerational effects, including decreased fertility, altered hormone levels, delayed puberty, and abnormal estrous cycles [19] [15]. These effects display sex-specific patterns, reflecting the complexity of epigenetic regulation in male and female reproductive systems [19].

Table 3: Evidence for Transgenerational Effects of Selected EDCs

| EDC | Model System | Exposure Window | Transgenerational Phenotypes (F1-F3+) | Associated Epigenetic Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinclozolin | Rat (in vivo) | Gestational [19] | Male infertility, spermatogenic defects, increased apoptosis [19] | Altered DNA methylation patterns in sperm [19] |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Mouse/Rat (in vivo) | Gestational or perinatal [19] [15] | Decreased fertility, ovarian defects, uterine abnormalities [19] [15] | Changes in uterine DNA methylation (e.g., HOXA10, ASCL2) [15] |

| Phthalates | Mouse (in vivo) | Prenatal [14] [19] | Reduced sperm count and motility, hormonal imbalances [14] [19] | Sperm DNA methylation changes, histone modifications [14] |

| Dioxins/PCBs | Human epidemiology & animal models | Prenatal [15] | Endometriosis, uterine disorders, reduced fertility [15] | Altered methylation of genes involved in uterine development [15] |

Methodologies for Epigenetic Analysis in EDC Research

Genome-Wide Epigenetic Profiling

Advanced high-throughput sequencing technologies enable comprehensive mapping of epigenetic modifications across the genome, providing powerful tools for identifying EDC-induced epimutations.

DNA Methylation Analysis:

- Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): Provides single-base resolution methylation maps of the entire genome. This is considered the gold standard for comprehensive DNA methylation analysis [19].

- Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS): A cost-effective method that enriches for CpG-rich regions, suitable for large-scale screening studies [19].

- Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS): Utilize microarray platforms (e.g., Illumina EPIC array) to profile methylation at >850,000 CpG sites in human population studies [20].

Histone Modification Profiling:

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): Identifies genome-wide binding sites for specific histone modifications or chromatin-associated proteins [18]. Critical for mapping H3K27me3 Polycomb domains and other repressive/active marks disrupted by EDCs.

Chromatin Accessibility Assessment:

- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using Sequencing (ATAC-seq): Maps open chromatin regions to identify accessible regulatory elements affected by EDC exposure [18].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for EDC Epigenetic Research. This diagram outlines a comprehensive approach from animal exposure modeling through multi-omics epigenetic analysis to functional validation of EDC-induced changes.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Epigenetic Studies in EDC Research

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | Small Molecule Inhibitors | 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (Decitabine) [18] | Investigate DNA methylation-dependent mechanisms; potential therapeutic applications |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Small Molecule Inhibitors | Vorinostat (SAHA) [18] | Probe role of histone acetylation in EDC toxicity; cancer therapy combinations |

| Antibodies for Histone Modifications | Immunochemical Reagents | H3K27me3, H3K4me3, H3K9ac [18] [13] | ChIP-seq, immunoblotting, immunofluorescence for histone mark detection |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Molecular Biology Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits [19] | Prepare DNA for methylation analysis by sequencing or pyrosequencing |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omics Platforms | Platform Technology | 10x Genomics Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression [13] | Simultaneously profile chromatin accessibility and gene expression in single cells |

| Organoid Culture Systems | Biological Models | Testicular, ovarian, endometrial organoids [18] | Human-relevant in vitro models for studying EDC effects on reproductive tissues |

The intricate interplay between DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs constitutes the molecular foundation of epigenetic reprogramming, a process highly vulnerable to disruption by EDCs, particularly during critical developmental windows. The evidence summarized in this technical review underscores that EDC-induced epimutations in germ cells can escape reprogramming and manifest as transgenerational inheritance of reproductive pathologies, including infertility and hormone-sensitive cancers. Future research priorities should include the systematic identification of susceptibility windows for specific EDCs, comprehensive mapping of transmitted epigenetic marks across generations using integrated multi-omics approaches, and elucidating the complex interactions between different epigenetic layers in transmitting environmental information. Furthermore, developing targeted epigenetic editing tools and pharmacological interventions to reverse or mitigate these deleterious epigenetic changes represents a promising frontier for therapeutic development in reproductive medicine. As the field advances, incorporating epigenetic endpoints into chemical risk assessment will be crucial for protecting reproductive health across generations.

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) paradigm establishes that environmental exposures during sensitive developmental periods reprogram physiological systems, increasing susceptibility to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) in adulthood and across generations [22] [23]. This review examines the critical windows of vulnerability, emphasizing the impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on the rising incidence of infertility and reproductive cancers. During developmental plasticity phases—from preconception through adolescence—exposures to environmental stressors like EDCs can cause subtle, permanent alterations in gene expression via epigenetic reprogramming rather than genetic mutations [24]. We synthesize epidemiological and experimental evidence, detailing the mechanisms by which EDCs disrupt hormonal signaling and provide structured data, methodological protocols, and essential research tools to advance this field.

The DOHaD framework has evolved from initial observations linking low birth weight to increased coronary heart disease risk in adulthood [22] [24]. The paradigm posits that the early life environment interacts with genetic variation to shape an organism's capacity to cope with its environment later in life [22]. While early research focused on nutritional influences, it is now clear that DOHaD comprehensively includes a range of environmental factors—including EDCs, stress, and pollutants—and their relevance to disease occurrence throughout the lifespan and across generations [22].

The central mechanism involves developmental plasticity, the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions during specific critical windows [25]. When environmental cues during development mismatch the actual postnatal environment, it can lead to predictive adaptive responses that increase disease susceptibility later in life [25]. This is particularly relevant for EDCs, which can interfere with the endocrine control of development, leading to altered tissue function and increased risk of reproductive disorders, including infertility and reproductive cancers [26] [27].

Critical Windows of Developmental Vulnerability

Development is a plastic process that exhibits varying sensitivity to environmental perturbations at different life stages. These critical windows represent periods when specific tissues and organs are most susceptible to reprogramming by environmental factors.

Defining the Windows of Vulnerability

The following table summarizes the major critical windows of vulnerability, their key developmental processes, and potential consequences of EDC exposure.

Table 1: Critical Windows of Developmental Vulnerability to Environmental Exposures

| Developmental Window | Key Developmental Processes | Potential Consequences of EDC Exposure |

|---|---|---|

| Preconception (Paternal & Maternal) | Germ cell development, genomic imprinting [23] | Epimutations in sperm [23] [25]; altered fetal programming [25] |

| In Utero (Fetal period) | Organogenesis, tissue differentiation, hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis establishment [22] [26] | Genital malformations (cryptorchidism, hypospadias) [26] [28]; altered reproductive tract development; increased cancer susceptibility [24] |

| Early Postnatal (Lactation, Infancy) | Immune system maturation, brain development, establishment of gut microbiome [23] | Altered immune function [23]; reprogrammed metabolic set points [23] |

| Childhood and Adolescence | Continued brain development, pubertal maturation, bone growth [22] [25] | Earlier puberty onset [29] [28]; altered neurodevelopment; entrainment of lifestyle behaviors [25] |

As illustrated, vulnerability begins prior to conception, with paternal and maternal exposures capable of influencing the germline [23] [25]. The most intense window spans the fetal period, when organ systems undergo rapid development and are exquisitely sensitive to hormonal disruption [22]. For instance, sexual differentiation is highly dependent on the fetal hormonal environment, and EDC exposure during this window can cause reproductive tract abnormalities that may not manifest until adulthood [26] [28]. Notably, vulnerability extends beyond birth for systems like the reproductive, immune, and neuroendocrine systems, which continue developing into childhood and adolescence [22] [25].

Vulnerability in the Context of EDCs and Reproductive Health

For reproductive health, EDCs such as phthalates, bisphenols, and PFAS can disrupt the tightly regulated pathways of sexual development, leading to disorders manifesting at birth (e.g., hypospadias) or later in life (e.g., reduced fertility, testicular cancer, polycystic ovary syndrome) [26] [27] [29]. These effects exhibit marked sex differences and are dependent on the timing and type of stressor [22]. The latency between developmental exposure and disease manifestation is a hallmark of DOHaD, with exposures potentially remaining clinically silent until a second "hit" or challenge occurs later in life [22] [24].

Molecular Mechanisms: Epigenetics and Pathway Disruption

The molecular basis for DOHaD effects primarily involves epigenetic reprogramming, where environmental exposures during development cause lasting changes in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself [23] [24].

Epigenetic Reprogramming

Environmental exposures during development can target the epigenome, leading to epimutations that increase disease susceptibility [24]. Key epigenetic mechanisms include:

- DNA methylation: The addition of methyl groups to CpG islands, typically repressing gene expression [24]. Prenatal exposure to famine has been associated with persistent DNA methylation changes at specific gene loci [24].

- Histone modifications: Methylation or acetylation of histone tails can activate or repress gene expression [24]. For example, H3K27 trimethylation typically represses gene expression [24].

- Non-coding RNAs: These can regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally and may be involved in transgenerational transmission [30].

These epigenetic modifications are particularly impactful during developmental periods when epigenetic patterns are being established and are more plastic [23] [24]. Once set, these patterns can be stable and long-lasting, potentially transmitted across generations via germline epigenetic inheritance [22] [24].

Disruption of Reproductive Endocrine Pathways

EDCs primarily interfere with the hormonal pathways critical for reproductive system development and function. The diagram below illustrates the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and key points of EDC disruption.

Figure 1: EDC Disruption of the Female Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis

EDCs can act through multiple mechanisms to disrupt this finely tuned system:

- Hormone mimicry: Binding to and activating estrogen receptors (e.g., BPA, phthalates) or androgen receptors [27] [28].

- Receptor antagonism: Blocking hormones from binding to their receptors [28].

- Altering hormone synthesis/metabolism: Interfering with enzymes involved in hormone production or breakdown [27].

- Epigenetic modification: Reprogramming gene expression in reproductive tissues [24].

For example, phthalate exposure has been associated with elevated FSH and lower estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone in adult women [27]. PFAS exposure has been linked to longer menstrual cycles and decreased estrogen and progesterone levels [27]. These disruptions during development can permanently alter the structure and function of reproductive organs, increasing susceptibility to conditions like infertility, endometriosis, and reproductive cancers [26] [28] [24].

Transgenerational Inheritance

Epigenetic reprogramming from developmental EDC exposure can potentially be transmitted to subsequent generations through germline transmission [22] [24]. The following diagram illustrates the mechanisms of transgenerational inheritance.

Figure 2: Transgenerational Inheritance of EDC Effects

True transgenerational inheritance requires the transmission of epigenetic marks through the germline to generations never directly exposed to the original EDC [22] [24]. Experimental evidence supports this phenomenon, demonstrating that EDC exposures during development can increase disease susceptibility in multiple subsequent generations [24].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

DOHaD research utilizes diverse experimental approaches to elucidate the mechanisms linking developmental exposures to later-life disease. The following table summarizes key methodological approaches for studying EDC effects within the DOHaD framework.

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for DOHaD-EDC Research

| Method Category | Specific Method/Assay | Key Applications in DOHaD-EDC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiological Studies | Cohort studies (e.g., NHANES), cross-sectional studies, case-control studies [27] [29] | Identifying associations between early-life EDC exposure and later reproductive outcomes (e.g., infertility, early menopause) [27] [29] |

| Animal Models | Rodent (mouse, rat) developmental exposure studies [27] [30] | Controlled investigation of critical windows, mechanisms, and transgenerational inheritance [27] [30] |

| In Vitro Systems | Ovarian follicle culture, cell lines (steroidogenic cells), primordial germ cell culture [27] | High-throughput screening of EDC effects on specific cell types and pathways [27] |

| Epigenetic Analyses | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq, histone modification profiling [24] | Identifying locus-specific and genome-wide epigenetic changes induced by EDCs [24] |

| Hormonal Assays | ELISA, LC-MS/MS, RIA for steroids (estradiol, progesterone), FSH, LH [27] | Quantifying EDC-induced alterations in endocrine profiles [27] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Perinatal EDC Exposure and Reproductive Assessment

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for assessing the effects of developmental EDC exposure on female reproductive outcomes in a rodent model, based on methodologies cited in the search results [27] [30].

1. Animal Model and Exposure Paradigm:

- Use timed-pregnant dams (e.g., Sprague-Dawley rats or C57BL/6 mice).

- Administer EDC (e.g., BPA, phthalates, or PFAS) via drinking water or oral gavage during critical windows:

- Gestational exposure: From gestational day (GD) 7 to parturition.

- Perinatal exposure: From GD7 through lactation until postnatal day (PND) 21.

- Include vehicle-control and positive control groups (e.g., known reproductive toxicant).

- Monitor dams for weight, food, and water intake.

2. Assessment of Offspring Outcomes:

- Prepubertal period (PND 1-21): Record anogenital distance, weight, and age at eye opening.

- Pubertal onset: Monitor for vaginal opening (females) daily from PND 28.

- Adult reproductive function (PND 60-90):

- Vaginal cytology: Daily smears for 3-4 weeks to assess estrous cyclicity.

- Fertility assessment: Mate exposed females with unexposed males; record time to impregnation, litter size, and offspring viability.

- Serum hormone analysis: Measure FSH, LH, estradiol, progesterone, and AMH via ELISA at different estrous stages.

- Ovarian histology: Collect ovaries at sacrifice; count primordial, primary, secondary, and antral follicles.

- Gene expression analysis: qRT-PCR or RNA-seq for ovarian steroidogenic genes (Star, Cyp11a1, Hsd3b1, Cyp19a1).

3. Transgenerational Studies:

- Breed exposed F1 females with unexposed males to generate F2 offspring.

- Continue breeding to F3 generation to assess true transgenerational effects [24].

- Assess similar reproductive endpoints in F2 and F3 generations.

This protocol allows for systematic evaluation of how developmental EDC exposure programs lifelong reproductive function and potential transgenerational impacts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and resources essential for investigating DOHaD mechanisms in EDC research, particularly focused on reproductive outcomes.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DOHaD-EDC Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Reference EDCs | Diethylstilbestrol (DES) [22], Bisphenol A (BPA) [27] [30], Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) [27], PFOS/PFOA [27] [29] | Positive controls for endocrine disruption studies; mechanistic investigations |

| Animal Models | Mouse (C57BL/6, CD-1), Rat (Sprague-Dawley, Long-Evans) [27] [30] | In vivo assessment of developmental programming and transgenerational inheritance |

| Hormone Assay Kits | ELISA kits for 17β-estradiol, progesterone, testosterone, FSH, LH, AMH [27] | Quantifying endocrine changes in serum, follicular fluid, and tissue culture media |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary ovarian follicles [27], steroidogenic cell lines (e.g., KGN, H295R), human endometrial organoids | In vitro screening of EDC effects on specific cell types and pathways |

| Epigenetic Tools | DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (5-azacytidine), histone deacetylase inhibitors (TSA), CRISPR/dCas9-epigenetic editors [24] | Mechanistic studies to establish causal relationships between epigenetic marks and phenotypes |

| Antibodies | Anti-histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K27me3), anti-steroidogenic enzymes (CYP11A1, CYP19A1), anti-hormone receptors (ERα, AR) [27] [24] | Western blot, immunohistochemistry, and ChIP assays to assess molecular changes |

These reagents enable researchers to dissect the complex relationships between developmental EDC exposures and later-life reproductive health outcomes across multiple biological levels, from molecular epigenetics to whole-organism physiology.

Discussion and Future Directions

The DOHaD paradigm provides a crucial framework for understanding how early-life EDC exposures contribute to the growing global burden of infertility and reproductive cancers. The evidence reviewed demonstrates that developmental exposures to EDCs during critical windows of vulnerability can reprogram reproductive systems through epigenetic mechanisms, with effects potentially spanning multiple generations.

Future research should prioritize:

- Elucidating mixture effects: Humans are exposed to complex mixtures of EDCs throughout life, yet most studies examine single compounds [22] [29].

- Identifying sensitive biomarkers: Developing biomarkers that predict individual susceptibility to EDC exposure and later-life disease risk [31].

- Adolescent interventions: Targeting adolescence as a critical window for intervention, as it represents a period where lifestyle behaviors become entrained and the next generation of parents are formed [25].

- Regulatory policy translation: Incorporating DOHaD principles into chemical risk assessment and regulatory frameworks to better protect vulnerable developmental periods [29].

The DOHaD perspective underscores that prevention strategies for reproductive disorders and cancers must begin early—before conception and during key developmental windows—rather than focusing solely on adult disease treatment. By identifying mechanisms of developmental reprogramming and critical windows of vulnerability, we can develop more effective interventions to break the transgenerational cycle of reproductive disease.

Within the broader investigation into the impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on infertility and reproductive cancers, the dysregulation of cellular redox homeostasis and programmed cell death emerges as a critical pathological mechanism. EDCs, including bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and pesticides, induce oxidative stress and apoptosis in reproductive tissues through receptor-mediated disruption of hormonal signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and epigenetic modifications. This whitepaper synthesizes current mechanistic insights, details key experimental methodologies for investigating these pathways, and provides resources to advance therapeutic development. The intricate interplay between oxidative damage and apoptotic signaling not only compromises gamete quality and steroidogenesis but may also contribute to the initiation and progression of reproductive malignancies, presenting a compelling target for future pharmacologic intervention.

The decline in global fertility rates and the rising incidence of certain reproductive cancers are increasingly linked to widespread exposure to EDCs [14] [32]. These exogenous chemicals, ubiquitous in plastics, pesticides, personal care products, and industrial effluents, interfere with the synthesis, transport, and action of endogenous hormones [6]. The reproductive system is particularly vulnerable due to its heavy reliance on precise hormonal communication for development and function. A growing body of evidence positions oxidative stress and the subsequent induction of apoptosis as a convergent pathway through which diverse EDCs exert their detrimental effects on both male and female reproductive health, disrupting processes from gametogenesis to embryonic implantation [33] [34] [35]. This document details the mechanisms, measurement, and research tools relevant to this field.

Molecular Mechanisms of EDC-Induced Cellular Damage

EDCs instigate cellular damage through a network of interconnected pathways that ultimately disrupt the delicate balance between cell survival and death.

Receptor-Mediated Disruption of Redox Signaling

EDCs can directly bind to hormone receptors, initiating signaling cascades that alter redox metabolism. For instance, BPA binds to estrogen receptors (ERα/ERβ) with nanomolar affinity (Ki ≈ 5–10 nM), leading to the upregulation of estrogen-responsive genes in tissues like Sertoli cells [14]. This receptor activation can trigger rapid, non-genomic pathways, including calcium influx and activation of the MAPK/ERK signaling cascade, which in turn can promote the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [14]. Similarly, phthalates and certain pesticides interfere with androgen and thyroid hormone receptors, disrupting the hormonal regulation of antioxidant defense systems and creating a pro-oxidative cellular environment [36].

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: The Epicenter of Oxidative Stress

Mitochondria, the primary source of cellular ATP, are also a major site of ROS generation and a key target for EDC toxicity. EDCs such as phthalates and pesticides impair mitochondrial electron transport chain function, leading to electron leakage and excessive production of superoxide anion (O₂⁻) [34]. This superoxide is dismutated into hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which can further react to form highly damaging hydroxyl radicals (•OH). Mitochondrial DNA is especially vulnerable due to its lack of protective histones, and its damage perpetuates a cycle of metabolic dysfunction and ROS production [35]. This oxidative burden depletes crucial antioxidants like glutathione (GSH) and overwhelms enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), leading to a state of sustained oxidative stress [33] [34].

The Apoptotic Cascade

Sustained oxidative stress directly activates the intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptotic pathway. ROS promote mitochondrial membrane permeability, triggering the release of cytochrome c into the cytoplasm. This leads to the formation of the apoptosome and the sequential activation of initiator (caspase-9) and executioner caspases (caspase-3, -7) [37]. The 17 kDa active form of caspase-3, a key executioner, cleaves cellular substrates, resulting in the systematic dismantling of the cell [38]. In the male reproductive system, this process damages spermatogenic cells, while in females, it can trigger apoptosis in granulosa cells and oocytes, impairing folliculogenesis and ovarian reserve [14] [33].

The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathway from EDC exposure to cellular damage.

Quantitative Biomarkers of Oxidative Damage and Apoptosis

Tracking oxidative stress and apoptosis requires quantifying specific molecular biomarkers. The following tables summarize key analytes and their significance.

Table 1: Key Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Capacity

| Biomarker | Description | Significance & Example Changes |

|---|---|---|

| ROS/RNS | Total levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. | Direct measure of pro-oxidant load. Increased ~2.2-fold in uterine explants after octylphenol exposure [38]. |

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) | Byproduct of lipid peroxidation. | Indicator of membrane damage. Elevated in oocytes exposed to DEHP [33]. |

| 8-OHdG | 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine, an oxidized DNA adduct. | Marker of oxidative DNA damage; found in oocytes after EDC exposure [33]. |

| GSH/GSSG Ratio | Ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione. | Primary indicator of cellular redox status. A decreased ratio signifies oxidative stress [33]. |

| SOD, CAT, GPx Activity | Key antioxidant enzyme activities. | CAT and GPx activity increased 2-fold and 2.3-fold, respectively, in sow-fed uterine explants upon EDC exposure, indicating a compensatory response [38]. |

Table 2: Key Biomarkers of Apoptosis

| Biomarker | Description | Significance & Experimental Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-3 Activation | Cleavage of pro-caspase-3 (35 kDa) to active form (17 kDa). | Executioner caspase; increased abundance in uterine explants after antiandrogen exposure [38]. Detected by Western blot. |

| DNA Fragmentation | Cleavage of nuclear DNA. | Hallmark of late-stage apoptosis. Quantified via TUNEL assay; increased in luminal and glandular epithelium after EDC exposure [38]. |

| BCL-2 Family Proteins | Regulators of mitochondrial apoptosis (e.g., BAX pro-apoptotic, BCL-2 anti-apoptotic). | Altered expression upon EDC exposure disrupts mitochondrial membrane integrity [37]. Detected by Western blot or immunohistochemistry. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility in investigating EDC-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis, standardized protocols are essential.

Ex Vivo Uterine Explant Model for Assessing EDC Effects

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, is ideal for studying direct tissue-specific effects while controlling for systemic variables [38].

1. Tissue Collection and Preparation:

- Source: Obtain uterine tissue from a model organism (e.g., 10-day-old piglets).

- Feeding Groups: Include both naturally fed (sow-fed) and formula-fed cohorts to investigate the protective role of bioactive factors in maternal milk.

- Dissection: Aseptically dissect uterine horns and place in ice-cold, oxygenated physiological buffer (e.g., DMEM/F-12).

- Explants: Slice uterine tissue into precise, uniform explants (e.g., 2x2x2 mm³).

2. Ex Vivo EDC Exposure:

- Treatment Groups: Randomly assign explants to culture wells.

- EDC Incubation: Expose explants to relevant EDCs (e.g., 10 µM 2-hydroxyflutamide (antiandrogen), 10 µM 4-tert-octylphenol (environmental estrogen), or 10 µM HPTE (methoxychlor metabolite)) for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours) in a controlled incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Controls: Include vehicle-treated control explants (e.g., DMSO <0.1%).

3. Oxidative Stress Analysis:

- ROS/RNS Quantification: Homogenize a subset of explants. Use fluorometric assays with dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) to measure total ROS/RNS levels.

- Antioxidant Enzyme Activity: Assay supernatants from homogenized tissue for CAT, GPx, GST, GR, and SOD activities using standardized colorimetric or kinetic assays.

4. Apoptosis and Proliferation Assessment:

- TUNEL Assay: Fix explants in 4% paraformaldehyde, embed in paraffin, section, and use a TUNEL kit to label DNA strand breaks for apoptotic cell counting via fluorescence microscopy.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Perform IHC on tissue sections for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) to quantify cell proliferation and for cleaved caspase-3 to confirm apoptosis.

- Western Blotting: Analyze total protein lysates from explants for apoptosis markers (e.g., pro/active caspase-3, BCL-2, BAX) and proliferation markers.

The workflow for this multi-faceted analysis is outlined below.

Assessing Sperm Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage

For male fertility research, analyzing sperm quality after EDC exposure is critical [34] [35].

1. Sperm Collection and EDC Exposure:

- Collect semen samples from model organisms or human donors (with consent).

- For in vitro studies, incubate motile sperm fractions with environmentally relevant concentrations of EDCs (e.g., BPA, phthalate metabolites) for several hours.

2. Sperm Quality and Redox Analysis:

- Computer-Assisted Sperm Analysis (CASA): Assess sperm concentration, motility, and kinematics.

- Chemiluminescence Assay: Use luminol or lucigenin probes to measure specific types of ROS directly from sperm suspensions.

- Lipid Peroxidation: Measure MDA levels in sperm samples via thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay.

- Sperm Chromatin Dispersion Test: Evaluate DNA fragmentation by quantifying the halos of dispersed DNA following acid denaturation and protein removal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and their applications for studying EDC-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EDC Studies

| Reagent / Assay Kit | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| DCFH-DA Probe | Cell-permeable fluorogenic dye used to quantitatively measure intracellular ROS/RNS levels in cells and tissue homogenates [38]. |

| Caspase-3 Activity Assay Kit | Colorimetric or fluorometric kit to detect and quantify the activation of the key executioner caspase, a definitive marker of apoptosis [37] [38]. |

| TUNEL Assay Kit | Fluorescence-based kit for in situ labeling of DNA fragmentation, allowing visualization and quantification of apoptotic cells within tissue sections [38]. |

| GSH/GSSG Ratio Assay Kit | Provides a sensitive method to determine the dynamic balance between reduced and oxidized glutathione, a central indicator of cellular redox state [33]. |

| Antibodies for BCL-2, BAX, PCNA | Essential for protein-level detection via Western blot or IHC to assess apoptotic signaling and cellular proliferation status [37] [38]. |

| Specific EDCs (e.g., BPA, MEHP, 4-tert-Octylphenol) | High-purity chemical standards used for in vitro and in vivo exposure studies to establish direct cause-effect relationships [14] [33] [38]. |

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a significant concern for human reproductive health worldwide. This technical review examines the specific profiles and mechanisms of action of Bisphenol-A (BPA), phthalates, pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and diethylstilbestrol (DES) in the context of infertility and reproductive cancers. Evidence from epidemiological, clinical, and toxicological studies demonstrates that these chemicals interfere with hormonal signaling through genomic and non-genomic pathways, disrupting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and causing epigenetic modifications. The pervasive presence of EDCs in consumer products, environmental media, and food chains leads to ubiquitous human exposure, with particular risk for vulnerable populations. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of each EDC's reproductive toxicity profile, detailed experimental methodologies for their study, and essential research tools for advancing this critical field of environmental health science.

Chemical Profiles and Reproductive Toxicity

Bisphenol-A (BPA)

BPA is an organic synthetic compound widely used in polycarbonate plastics, epoxy resins, and thermal paper products. Global industrial production reaches billions of pounds annually, resulting in ubiquitous human exposure through food packaging, consumer goods, and environmental media [39] [40].

Table 1: BPA Reproductive Toxicity Profile

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Global Production | Billions of pounds annually [40] |

| Detection | Found in multiple human body fluids [39] |

| Male Effects | Increased sperm alterations, altered reproductive hormone levels, testicular atrophy [39] |

| Female Effects | Hormonal imbalances, reduced ovarian reserve, infertility, PCOS, endometriosis, fibroids [39] |

| Key Mechanisms | Estrogen receptor agonism, androgen receptor antagonism, HPG axis disruption [40] |

| Exposure Concern | Adverse effects observed even at low exposure levels [40] |

BPA exerts its endocrine-disrupting effects primarily through estrogen receptor agonism and androgen receptor antagonism, leading to disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis [40]. It can cause detrimental changes to both male and female reproductive health through both genomic and non-genomic mechanisms, with epigenetic modifications playing a significant role in its long-term effects [39].

Phthalate Esters (PAEs)

Phthalates are high-production volume synthetic compounds extensively utilized as plasticizers to enhance flexibility in plastics, with global production approximately 8 million tons annually [41]. They represent 80-85% of all plasticizers produced and are found in medical devices, cosmetics, food packaging, and construction materials [41].

Table 2: Phthalate Reproductive Toxicity Profile

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Global Production | ~8 million tons annually (80-85% of plasticizers) [41] |

| Common Uses | Medical devices, cosmetics, food packaging, construction materials [41] |

| Male Effects | Testicular dysgenesis syndrome, reduced fertility capacity [41] |

| Female Effects | Disrupted follicle growth, increased oxidative stress, follicle death, faster ovarian reserve depletion [42] |

| Key Mechanisms | HPG axis dysfunction, abnormal gonadal hormone secretion, oxidative stress, apoptosis [41] [42] |

| Research Focus | Mixed exposures, dose-response relationships, toxicological mechanisms [41] |

Phthalates are recognized endocrine disruptors that interfere with the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, resulting in abnormal secretion of gonadal hormones and alterations in the synthesis of sex hormone receptors [41]. In females, phthalates can disrupt follicle growth patterns, increase oxidative stress, and cause follicle death, potentially leading to infertility and earlier reproductive senescence [42].

Pesticides

Pesticides encompass various chemical classes including herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides, many with endocrine-disrupting properties. Extensive evidence links pesticide exposure to numerous cancers and reproductive disorders [43] [44] [45].

Table 3: Pesticide Cancer Associations Evidence Base

| Cancer Type | Number of Studies | Studies Finding Association | Evidence Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 32 | 23/27 (85%) | Strong [43] |

| Leukemia | 23 | 14/16 (88%) | Strong [43] |

| Brain Cancer | 11 | 11/11 (100%) | Consistent [43] |

| Prostate Cancer | 10 | 8/8 (100%) | Consistent [43] |

| Bladder Cancer | Multiple | Positive associations | Dose-dependent [44] |

Pesticides have been associated with reproductive toxicity through multiple pathways. Recent bibliometric analyses identify "bisphenol a," "infertility," "testicular dysgenesis syndrome," "endocrine disrupting chemicals," and "oxidative stress" as research hotspots, indicating focused investigation into reproductive endpoints [41]. The association between pesticide exposure and cancer risk has been found to be comparable to smoking for some cancer types [45].

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) and Persistent EDCs

PCBs, polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), organochlorine pesticides (OCPs), and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) constitute persistent EDCs characterized by long biological half-lives, environmental persistence, and bioaccumulation potential [46] [47]. Though many have been banned or phased out, exposure remains concerning due to environmental persistence and propensity to leach from consumer products [47].

These persistent EDCs can dysregulate the stress response by disrupting the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axes [46]. In studies of Black women, specific EDCs including PCB 118, PBDE 99, and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) were associated with higher perceived stress scores, indicating potential disruption of neuroendocrine pathways relevant to reproductive function [46].

Diethylstilbestrol (DES)