Endocrine Regulation of Circadian Rhythms: Molecular Mechanisms, Systemic Impacts, and Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the intricate bidirectional relationship between the endocrine system and circadian biology.

Endocrine Regulation of Circadian Rhythms: Molecular Mechanisms, Systemic Impacts, and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the intricate bidirectional relationship between the endocrine system and circadian biology. It explores the foundational molecular architecture of circadian clocks and their systemic synchronization by hormonal signals. The content delves into advanced methodologies for monitoring circadian endocrine rhythms and investigates the profound health consequences of circadian disruption, including metabolic syndrome, cardiometabolic disorders, and cognitive impairments. Furthermore, it evaluates emerging therapeutic strategies such as chronotherapy and time-restricted eating, which leverage circadian principles for optimized drug efficacy and metabolic health. By integrating genetic, physiological, and clinical perspectives, this review aims to bridge fundamental circadian science with translational applications for novel disease interventions and therapeutic development.

The Molecular Clockwork: Unraveling Core Mechanisms and Hormonal Synchronization

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus is the master circadian pacemaker in mammals, responsible for generating and coordinating daily ~24-hour cycles of physiology and behavior [1] [2]. This bilateral structure, containing approximately 20,000 neurons in mice and humans, synchronizes virtually all bodily processes—from sleep-wake cycles to hormone secretion and metabolism—with the external environment [3] [4] [5]. Its unique ability to generate autonomous, precise circadian rhythms while remaining responsive to environmental time cues makes it a critical regulator of organismal function. Within the broader context of endocrine regulation research, understanding SCN architecture is paramount, as this central clock exerts profound control over hormonal rhythms, including those of cortisol, melatonin, and reproductive hormones [6] [7]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of SCN organization, from its molecular mechanisms to its network-level properties, and details experimental approaches for its study, offering researchers a comprehensive resource for investigating circadian neuroendocrinology.

Anatomical and Neurochemical Organization

The SCN exhibits a sophisticated heterogeneous structure that underlies its function as a precise timekeeper. Located in the anterior hypothalamus directly above the optic chiasm, the nucleus is divided into two primary subregions: the ventrolateral "core" and the dorsomedial "shell" [1] [2] [7]. This anatomical specialization is consistent across mammalian species, though subtle morphological differences exist [2] [7].

Table: Key Neurochemical Subregions of the SCN

| Subregion | Primary Neuropeptides | Afferent Inputs | Functional Specialization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core (Ventrolateral) | Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), Gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) [1] [7] | Retinohypothalamic tract (RHT), Geniculohypothalamic tract (GHT) [1] [2] | Receives and processes direct photic input; mediates entrainment to light-dark cycles [1] [3] |

| Shell (Dorsomedial) | Arginine vasopressin (AVP) [1] [7] | Primarily from SCN core; other hypothalamic areas [2] [7] | Generates autonomous rhythmicity; projects to hypothalamic targets for rhythm output [1] [7] |

This neuroanatomical organization creates a functional processing pathway where photic information received by the core is integrated and communicated to the shell, which in turn generates coherent rhythmic outputs to downstream systems [2] [7]. The core region is essential for producing rhythmic output signals, as its destruction abolishes circadian rhythms in hormone secretion, body temperature, and locomotor activity [7].

Molecular Mechanisms of Circadian Timekeeping

The SCN generates circadian rhythms through a core transcriptional-translational feedback loop (TTFL) that operates within individual SCN neurons [2] [4]. This cell-autonomous molecular clock consists of interlocking feedback loops that create approximately 24-hour oscillations in clock gene expression.

The core feedback loop begins with CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins forming heterodimers that activate transcription of Period (Per1, Per2, Per3) and Cryptochrome (Cry1, Cry2) genes by binding to E-box elements in their promoters [2] [4]. Following translation, PER and CRY proteins gradually accumulate in the cytoplasm, form heterodimers, and translocate to the nucleus where they inhibit CLOCK:BMAL1-mediated transcription, thereby repressing their own expression [2]. This negative feedback loop spans approximately 24 hours due to strategic delays in transcription, translation, and protein nuclear translocation. Subsequent degradation of PER and CRY proteins by ubiquitin ligase complexes (including β-TrCP1 and FBXL3) relieves the transcriptional inhibition, allowing the cycle to begin anew [2].

Additional stability is provided by auxiliary feedback loops, most notably through REV-ERBα, which inhibits Bmal1 transcription by binding to ROR elements, creating an interlocking loop that enhances rhythm robustness and precision [2] [4]. Recent evidence indicates that post-transcriptional and metabolic mechanisms also contribute to circadian timing, with membrane depolarization, intracellular calcium, and cAMP acting as both inputs to and outputs of the transcriptional clock, potentially forming reinforcing loops that stabilize rhythmicity [2].

Network Properties and Synchronization

While individual SCN neurons can generate circadian oscillations in isolation, the network properties of the intact SCN are essential for its precision and robustness as a master pacemaker [2] [4]. The SCN network synchronizes its cellular oscillators, reinforces their rhythms, responds to environmental inputs, increases robustness to genetic perturbations, and enhances temporal precision [2].

Communication within the SCN network involves multiple neurotransmitter and signaling systems. GABA serves as the primary fast neurotransmitter, with most SCN neurons being GABAergic [2]. The effects of GABA vary across the circadian cycle, exhibiting excitatory actions by day and inhibitory effects by night, though the mechanisms underlying this dual effect remain under investigation [1]. Neuropeptides play crucial roles in intra-SCN communication, with VIP-VPAC2 signaling in the core serving as a key synchronizer of cellular oscillations [1] [2]. This peptide signaling is particularly important for maintaining internal synchrony within the nucleus.

The SCN exhibits spatial and temporal waves of activity across the nucleus, with neurons in the dorsomedial shell typically phase-advanced relative to those in the ventrolateral core [7] [5]. This ordered pattern of activation was demonstrated in studies showing that Per1 expression begins in the shell and spreads slowly through the nucleus over approximately 12 hours before receding [7]. The phase distribution across the SCN network is not fixed but can be reconfigured in response to environmental changes, such as seasonal variations in day length, enabling the SCN to encode temporal information beyond the 24-hour cycle [2].

Table: SCN Network Characteristics and Functional Consequences

| Network Property | Mechanistic Basis | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronization | VIP/VPAC2 signaling; GABAergic transmission [1] [2] | Coherent rhythmic output across the entire nucleus [2] |

| Phase Wave | Topographically organized circuitry; differential phasing of regional activation [7] [5] | Temporal expansion of SCN output signals; seasonal encoding [2] |

| Robustness | Intercellular coupling; redundant signaling systems [2] [4] | Resistance to genetic and environmental perturbations [2] |

| Precision | Network-level averaging of cellular oscillations [2] [4] | Higher temporal accuracy than individual cellular oscillators [2] |

Connectivity along the caudal-to-rostral axis appears particularly important for maintaining proper network function, with computational modeling suggesting that coronal slicing (which disrupts this axis) has the most detrimental effect on oscillatory dynamics, while horizontal slicing has the least impact [5].

Endocrine Regulation and Output Pathways

The SCN regulates endocrine function through multiple efferent pathways that convey temporal information to peripheral tissues. The major monosynaptic efferents from the SCN project to hypothalamic nuclei including the subparaventricular zone, medial preoptic nucleus, dorsomedial hypothalamus, and paraventricular nucleus [1] [8]. These projections ultimately regulate the secretion of hormones including melatonin, cortisol, and reproductive hormones [1] [6] [7].

The SCN regulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis through AVP projections from the shell to the PVN, which generates the circadian rhythm in corticotropin-releasing hormone release and ultimately cortisol secretion [6] [7]. Additionally, the SCN influences adrenal sensitivity to ACTH via autonomic innervation through the splanchnic nerve, and the adrenal gland's intrinsic circadian clock gates its response to ACTH [6]. This multilayered regulation creates a robust circadian rhythm in glucocorticoid secretion that peaks just before the active phase [6].

The melatonin rhythm is generated through a polysynaptic pathway from the SCN to the pineal gland. During the night, SCN efferents ultimately trigger norepinephrine release in the pineal, stimulating melatonin production through β-1 and α-1 adrenergic receptors on pinealocytes [1] [6]. Melatonin serves as a hormonal signal of darkness duration, with production prolonged during long winter nights and shortened in summer, thus communicating seasonal information to tissues throughout the body [1] [6].

The SCN also regulates metabolic hormones through both direct and indirect pathways. The dorsomedial hypothalamus, a major recipient of SCN output, is crucial for generating circadian rhythms in feeding behavior, thereby influencing insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and other metabolic hormones [6] [8]. The timing of food intake can itself reset peripheral clocks, creating a feedback loop between metabolic state and circadian timing [6].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Monitoring SCN Oscillations

Advanced techniques enable real-time monitoring of SCN molecular rhythms. The PER2::LUCIFERASE (PER2::LUC) system is a cornerstone method, using SCN tissue slices from genetically modified mice expressing a PER2-luciferase fusion protein [5]. When cultured with luciferin, bioluminescence intensity reflects PER2 expression levels, allowing long-term, real-time monitoring of circadian gene expression in intact SCN slices [5]. This approach revealed spatiotemporal waves of PER2 expression across the SCN but is limited by tissue slicing, which disrupts intrinsic connectivity and alters network dynamics [5].

Emerging volumetric imaging techniques address this limitation. Intact, unsliced SCN can be studied using light-sheet microscopy combined with tissue clearing methods such as iDISCO, enabling visualization of PER2 expression throughout the entire nucleus without disrupting its native circuitry [5]. This approach preserves the complex three-dimensional architecture of the SCN and provides a more complete picture of its network dynamics.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for SCN Circadian Research

| Research Tool | Composition/Type | Primary Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| PER2::LUC Mouse Model | Transgenic mouse expressing PER2-luciferase fusion protein [5] | Real-time monitoring of molecular clock function in SCN slices via bioluminescence [5] |

| Luciferin | D-luciferin substrate | Culture medium additive for bioluminescence imaging in PER2::LUC systems [5] |

| iDISCO Protocol | Tissue clearing reagents | Preparation of intact SCN for volumetric imaging using light-sheet microscopy [5] |

| Calcium Indicators | Genetically encoded or chemical fluorescent dyes | Monitoring rhythmic neuronal activity in SCN slices or in vivo [2] |

| VIP/AVP Receptor Antagonists | Pharmacological inhibitors | Investigating neuropeptide signaling in SCN network synchronization [1] [2] |

Experimental Protocol: PER2::LUC Rhythm Monitoring in SCN Slices

Objective: To characterize circadian rhythms of gene expression in SCN explants from PER2::LUC mice [5].

Tissue Preparation:

- Sacrifice PER2::LUC reporter mice during the light phase under appropriate anesthesia.

- Rapidly dissect brain and prepare coronal hypothalamic slices (150-250 μm thickness) using a vibratome in ice-cold, oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid.

- Microdissect the SCN region from surrounding hypothalamic tissue.

Culture Establishment:

- Place SCN explants on culture membrane inserts in 35mm dishes containing 1.2mL of culture medium (e.g., DMEM with HEPES, B27 supplement, and 0.1mM luciferin).

- Seal dishes with coverslips using silicone grease to prevent evaporation and maintain sterility.

Data Acquisition:

- Transfer cultures to a light-tight chamber maintained at 36°C.

- Collect bioluminescence signals using photomultiplier tubes or cooled CCD cameras at 10-60 minute intervals for 5-10 days.

- Maintain constant temperature and darkness throughout imaging.

Data Analysis:

- Subtract baseline drift using 24-hour moving averages.

- Fit damped cosine curves or use FFT-NLLS algorithms to determine period, phase, and amplitude of rhythms.

- Generate phase maps from image data to visualize spatiotemporal wave patterns.

This protocol yields precise measurements of circadian period and amplitude in SCN tissue, though it should be noted that slicing orientation affects results due to disruption of specific connectivity axes [5].

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

SCN dysfunction has significant clinical consequences, with circadian disruption implicated in various mood disorders, sleep disorders, and metabolic conditions [1] [6]. Patients with major depressive disorder frequently show phase-delayed circadian rhythms and disrupted sleep architecture, while bipolar disorder exhibits contrasting phase abnormalities—phase-advanced during manic episodes and phase-delayed during depressive episodes [1]. Seasonal affective disorder is strongly linked to dysfunctional serotonergic pathways and abnormal melatonin rhythms [1] [6].

Chronopharmacology represents a promising therapeutic approach that leverages knowledge of circadian regulation to optimize drug timing [1]. Because the absorption, metabolism, and excretion of many pharmaceuticals vary across the circadian cycle, coordinating drug administration with internal biological time can enhance efficacy and reduce side effects [1]. This is particularly relevant for endocrine therapies, given the robust circadian rhythms in hormone secretion and receptor expression [6].

The SCN also mediates the health consequences of modern lifestyle challenges, including shift work, jet lag, and artificial light exposure at night [1] [6]. These conditions create misalignment between the central SCN clock and peripheral tissue clocks, as well as between internal circadian rhythms and external environmental demands. Such misalignment is associated with increased risks of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers, highlighting the importance of maintaining proper circadian alignment for human health [6].

The suprachiasmatic nucleus represents a remarkable integration of molecular precision and network-level computation. Its sophisticated architecture—from the cell-autonomous transcriptional-translational feedback loops to the carefully orchestrated neurochemical and temporal organization across its core and shell subregions—enables it to function as the body's master circadian pacemaker. The SCN's ability to synchronize with environmental light-dark cycles while maintaining robust internal timekeeping allows it to coordinate endocrine rhythms essential for health and homeostasis. Ongoing research continues to reveal how SCN network properties emerge from its constituent cellular oscillators and how these properties enable the encoding of seasonal and other temporal information. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding SCN architecture provides not only fundamental insights into circadian biology but also promising avenues for therapeutic intervention through chronopharmacological approaches that align treatments with the body's internal temporal architecture.

Circadian rhythms are endogenous, ~24-hour oscillations in physiological processes that allow organisms to anticipate and adapt to daily environmental changes. These rhythms are governed by a cell-autonomous molecular clockwork present in nearly every cell, which is hierarchically coordinated by a master pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus [9] [10]. The SCN receives light input from the retina and synchronizes peripheral oscillators throughout the body via neurohumoral signals, including endocrine pathways [9] [11]. This master clock integrates external environmental changes and internal physiological signals to generate natural oscillations of secreted endocrine signals such as melatonin, cortisol, and thyrotropin, which in turn regulate diverse biological processes [12] [10]. The core molecular mechanism generating these rhythms consists of interlocked transcriptional-translational feedback loops (TTFLs) involving several core clock components: the activators CLOCK and BMAL1, the repressors PER and CRY, and the stabilizing nuclear receptors REV-ERB and ROR [9] [13] [10]. This molecular oscillator not only drives circadian rhythmicity but also temporally gates endocrine function, creating a crucial bidirectional relationship between the circadian system and endocrine regulation [12] [14].

Molecular Architecture of the Core Circadian Clock

The Primary Negative Feedback Loop

The core negative feedback loop consists of the transcriptional activators CLOCK (or its paralog NPAS2 in some tissues) and BMAL1, which form a heterodimer that binds to E-box enhancer elements (CACGTG) in the promoter regions of target genes [10]. This CLOCK-BMAL1 complex drives the transcription of period (Per1, Per2, Per3) and cryptochrome (Cry1, Cry2) genes [9] [10]. After translation, PER and CRY proteins form multimeric complexes in the cytoplasm that translocate back into the nucleus to inhibit CLOCK-BMAL1-mediated transcription, thus completing a 24-hour feedback cycle [9] [10]. The timing of this loop is regulated by post-translational modifications, particularly phosphorylation by casein kinase 1ε/δ (CK1ε/δ) and adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK), which tag PER and CRY proteins for ubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome complex [10].

The Stabilizing Auxiliary Loop

A crucial auxiliary feedback loop involves the nuclear receptors REV-ERB (α and β) and ROR (α, β, and γ), which regulate Bmal1 transcription and provide stability to the core oscillator [9] [13] [15]. The CLOCK-BMAL1 heterodimer activates transcription of Rev-erbα and Rev-erbβ genes [9]. REV-ERB proteins then compete with ROR activators for binding to ROR response elements (ROREs) in the Bmal1 promoter [9] [15]. While RORs activate Bmal1 transcription, REV-ERBs function as transcriptional repressors by recruiting the nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR)-histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) complex [9] [13]. This competing activation and repression creates precisely timed anti-phase oscillations of Bmal1 transcription relative to Per and Cry expression [9] [15].

Table 1: Core Components of the Mammalian Circadian Clock Mechanism

| Component | Type | Function | Role in Feedback Loop |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLOCK | Transcription factor | Forms heterodimer with BMAL1; histone acetyltransferase activity | Positive element; activates Per, Cry, Rev-erb transcription |

| BMAL1 | Transcription factor | Forms heterodimer with CLOCK; binds E-box elements | Positive element; essential for rhythm generation |

| PER | Repressor protein | Forms complex with CRY; inhibits CLOCK-BMAL1 activity | Negative element; rhythm period determination |

| CRY | Repressor protein | Forms complex with PER; inhibits CLOCK-BMAL1 activity | Negative element; strong transcriptional repression |

| REV-ERB | Nuclear receptor | Represses Bmal1 transcription; competes with ROR | Negative element in auxiliary loop; stabilizes rhythms |

| ROR | Nuclear receptor | Activates Bmal1 transcription; competes with REV-ERB | Positive element in auxiliary loop; regulates rhythm amplitude |

Tissue-Specific Variations in Clock Architecture

While the core clock mechanism is present in nearly all cells, tissue-specific variations exist in the relative importance of different feedback loops. Computational modeling of circadian gene expression across different tissues has revealed that the essential feedback loops differ between tissues, pointing to specific design principles within the hierarchy of mammalian tissue clocks [16]. For example, self-inhibitions of Per and Cry genes are characteristic for models of SCN clocks, whereas in liver models, multiple loops act in synergy and are connected by a repressilator motif (a system of three mutually repressing genes) [16]. In heart tissue, Bmal1–Rev-erb-α loops appear to be particularly important, while repressilator motifs are rarely found in brain, heart, and muscle tissues due to the earlier phases and small amplitudes of Cry1 in these tissues [16]. This tissue-specific use of a network of co-existing synergistic feedback loops could account for functional differences between organs and their specific endocrine relationships.

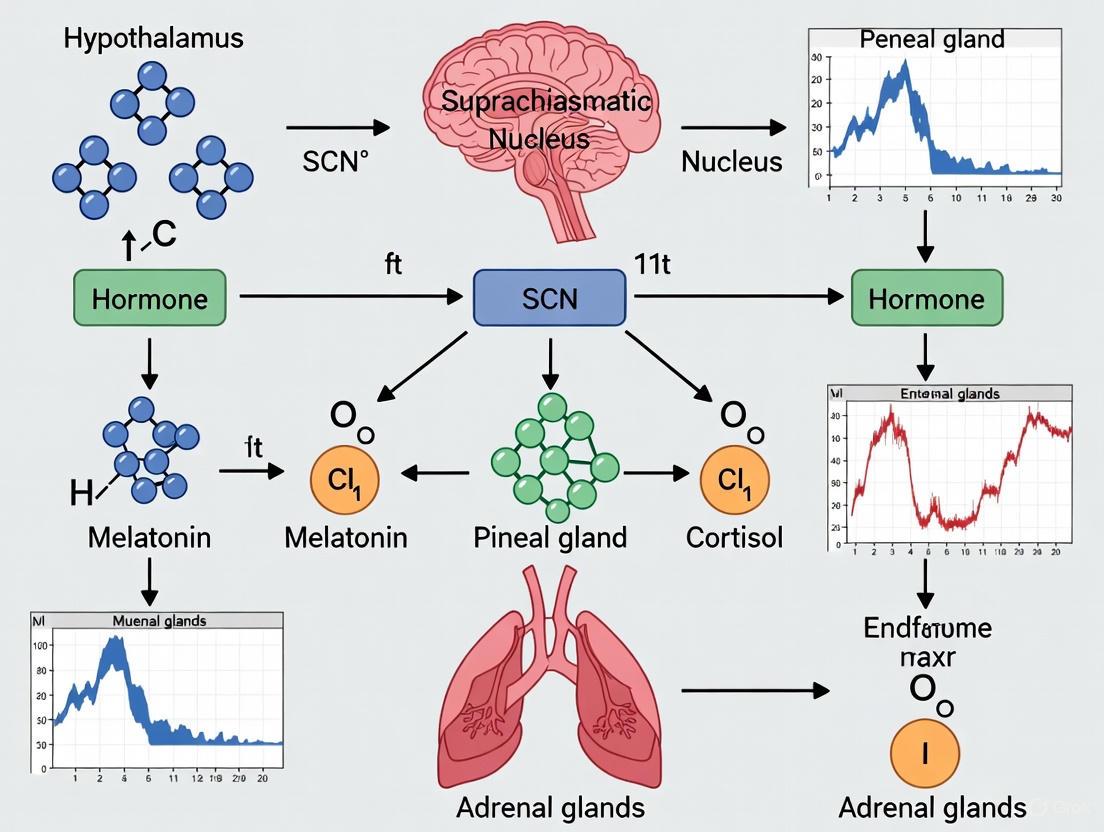

Diagram 1: Core transcriptional-translational feedback loops of the mammalian circadian clock. The core negative feedback loop (blue/red) and auxiliary stabilizing loop (gray/green) interact to generate robust ~24-hour oscillations. REV-ERB and ROR compete for binding to ROR response elements (ROREs) in the BMAL1 promoter.

Experimental Analysis of Circadian Clock Mechanisms

Genetic Manipulation Approaches

Understanding the hierarchical importance of clock components has required sophisticated genetic approaches. Functional redundancy between REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ was demonstrated through combined gene knockout and RNA interference, showing that both are required for rhythmic Bmal1 expression but are functionally redundant [17]. In contrast, the RORs contribute to Bmal1 amplitude but are dispensable for Bmal1 rhythm [17]. Importantly, cells deficient in both REV-ERBα and β function, or those expressing constitutive BMAL1, were still able to generate and maintain normal Per2 rhythmicity, underscoring the resilience of the intracellular clock mechanism [17]. This demonstrates that while the auxiliary loop contributes to fine-tuning of the core loop, its primary function is to provide discrete waveforms of clock gene expression for control of local physiology rather than being absolutely essential for rhythm generation [17].

Table 2: Key Genetic Manipulation Studies in Circadian Rhythm Research

| Genetic Approach | Key Findings | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| REV-ERBα/β double knockout | REV-ERBα and β are functionally redundant; required for rhythmic Bmal1 expression but not essential for core clock function | Fibroblast cell culture | [17] |

| ROR knockdown | RORs contribute to Bmal1 amplitude but are dispensable for Bmal1 rhythm | Cell culture models | [17] |

| Constitutive BMAL1 expression | Bmal1 mRNA/protein cycling not necessary for basic clock function; core PER/CRY loop sufficient for rhythm generation | Fibroblast cell culture; Bmal1-/- mice | [17] |

| Tissue-specific modeling | Essential feedback loops differ between tissues; Per/Cry auto-inhibition dominant in SCN, repressilator motifs in liver | Computational modeling of multiple tissues | [16] |

Real-Time Monitoring of Circadian Rhythms

Longitudinal monitoring of circadian rhythms in real-time has been crucial for understanding clock dynamics. Real-time bioluminescence monitoring of gene expression using reporters such as Per2-luciferase has allowed researchers to assess the persistence of circadian rhythmicity in various genetic backgrounds [17]. This approach circumvents the limitations of behavioral analysis, which may not faithfully reflect intracellular clock function due to pleiotropic effects and functional redundancy [17]. For endocrine research, engineered cells with genomically integrated switch components using transposase-based systems have enabled the establishment of clonal cell populations with robust circadian characteristics [12]. Single cell clones can be isolated via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and high-performing clones can be identified based on transgene expression and fold induction (e.g., up to 40-fold induction in response to circadian signals) [12].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for analyzing core clock components and their therapeutic applications. The process begins with genetic manipulation, proceeds through circadian rhythm assessment, and culminates in therapeutic development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Circadian Rhythm Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioluminescence Reporters | Per2-luciferase, Bmal1-luciferase | Real-time monitoring of promoter activity | Longitudinal tracking of circadian rhythms in living cells and tissues |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, RNA interference | Targeted knockout/knockdown of clock genes | Functional analysis of specific clock components |

| Cell Line Models | HEK293T, CHO, hMSC, primary fibroblasts | In vitro testing of circadian mechanisms | Screening of genetic manipulations and drug effects |

| Nuclear Receptor Ligands | REV-ERB agonists (SR9009), ROR inverse agonists | Pharmacological modulation of auxiliary loop | Testing stability and resilience of circadian oscillations |

| Hormonal Sensors | Melatonin receptor assays, cortisol measurements | Monitoring endocrine-circadian interactions | Studying bidirectional clock-endocrine relationships |

| Computational Tools | Global optimization algorithms, tissue-specific models | Analysis of complex circadian networks | Identifying essential feedback loops in different tissues |

Circadian-Endocrine Integration and Therapeutic Implications

Endocrine Regulation of Circadian Rhythms

The circadian system exhibits profound bidirectional relationships with endocrine pathways. The SCN controls peripheral oscillators through autonomic innervation of peripheral tissues, endocrine signaling (glucocorticoids), body temperature, and feeding-related cues [10]. Glucocorticoids in particular serve as humoral entraining signals for peripheral oscillators, as glucocorticoid-response elements (GREs) are present in promoter regions of core clock components, enabling glucocorticoids to regulate transcriptional activation of clock genes and clock-related genes [10]. Additionally, circadian regulation of host-microbiota crosstalk has emerged as an important factor in systemic physiology, with microbial-derived metabolites (short-chain fatty acids, bile acids, indoles) acting as circadian cues, while host clock genes modulate microbial ecology and intestinal barrier integrity [14]. This establishes a dynamic circadian-microbiota axis that synchronizes nutrient processing, hormonal secretion, immune surveillance, and neural signaling [14].

Chronotherapy and Circadian-Targeted Therapeutics

The growing understanding of circadian biology has spurred development of therapeutic approaches targeting the molecular clock. Chronotherapy involves aligning treatments with circadian rhythms to maximize efficacy and minimize side effects, while direct circadian modulation aims to correct underlying rhythm disturbances using chronobiotics [11]. REV-ERB has emerged as a particularly promising therapeutic target, as it regulates glucose and lipid metabolism, inflammation, autophagy, ferroptosis, and mitochondrial function in addition to its circadian functions [9]. Pharmacological activation of REV-ERB has shown promise in reducing pathological gene expression and improving outcomes in myocardial infarction and heart failure preclinical models [9]. For endocrine applications, synthetic biology approaches have engineered melatonin-responsive gene switches that can translate circadian inputs into therapeutic outputs, demonstrating potential for cell-based therapies for obesity-dependent type-2 diabetes through circadian-regulated GLP-1 expression [12]. Nanomaterial-enabled drug delivery systems are also being developed for circadian medicine, leveraging liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and mesoporous silica nanoparticles to deliver drugs to specific targets over sustained periods aligned with circadian biology [11].

The core transcriptional-translational feedback loops comprising CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, CRY, REV-ERB, and ROR represent a fundamental biological mechanism that orchestrates ~24-hour rhythms in virtually all physiological processes, with particularly profound implications for endocrine regulation. The hierarchical organization of this system, with the SCN as master pacemaker coordinating peripheral oscillators through endocrine and neural pathways, ensures temporal coordination across tissues and systems. The resilience of the core PER/CRY feedback loop, stabilized by the auxiliary REV-ERB/ROR loop, provides both robustness and flexibility to adapt to changing environmental conditions. From a therapeutic perspective, targeting core clock components—particularly REV-ERB—holds significant promise for treating metabolic, cardiovascular, and endocrine disorders, while chronotherapeutic approaches leverage circadian timing to optimize drug efficacy and safety. Future research will continue to elucidate tissue-specific clock variations and their implications for endocrine health, potentially leading to more personalized circadian medicine approaches.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) serves as the master circadian pacemaker, coordinating daily rhythms in physiology and behavior. This whitepaper details the neural and endocrine output pathways through which the SCN synchronizes peripheral clocks throughout the body. The SCN achieves temporal coordination via autonomic nervous system outputs and hormonal signaling cascades, including regulation of glucocorticoids and melatonin. Disruption of these pathways contributes to metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegeneration. Emerging chronotherapeutic strategies that target these synchronization mechanisms offer promising avenues for optimizing drug efficacy and developing novel treatments for circadian-related disorders. Understanding these systemic synchronizers provides a critical foundation for advancing circadian medicine in clinical practice and drug development.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus functions as the central circadian pacemaker in mammals, coordinating a network of peripheral clocks located throughout the brain and body [18] [19]. This approximately 20,000-neuron structure in rodents generates endogenous ~24-hour rhythms through cell-autonomous transcriptional-translational feedback loops (TTFLs) involving core clock genes such as CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, and CRY [19]. While individual SCN neurons can generate independent circadian oscillations, network interactions within the SCN enhance rhythm amplitude and robustness through synaptic signaling involving gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) [19].

The SCN receives photic input directly from the retina via the retinohypothalamic tract, aligning internal circadian time with the external light-dark cycle [18]. However, the SCN also integrates non-photic cues, including metabolic and hormonal signals, to maintain optimal temporal coordination [19]. The primary function of the SCN is to synchronize peripheral oscillators in organs and tissues, which it accomplishes through two principal output pathways: direct neural projections and systemic endocrine signals [18] [20]. These synchronized outputs regulate daily rhythms in physiology, including sleep-wake cycles, hormone secretion, metabolism, and cardiovascular function.

Table 1: Core Clock Genes and Proteins in the SCN TTFL

| Gene/Protein | Function in TTFL | Role in Rhythm Generation |

|---|---|---|

| CLOCK | Transcriptional activator | Forms heterodimer with BMAL1; binds E-box elements |

| BMAL1 | Transcriptional activator | Forms heterodimer with CLOCK; initiates transcription of Per and Cry genes |

| PER1-3 | Transcriptional repressors | Accumulate, form complexes with CRY proteins, inhibit CLOCK:BMAL1 activity |

| CRY1/2 | Transcriptional repressors | Stabilize PER proteins, facilitate nuclear translocation, suppress transcription |

| REV-ERBα/β | Auxiliary loop regulator | Suppresses Bmal1 transcription by competing for RORE elements |

| RORα/β | Auxiliary loop regulator | Activates Bmal1 transcription by competing for RORE elements |

Neural Output Pathways from the SCN

The SCN coordinates peripheral circadian rhythms through direct neural projections to key hypothalamic nuclei, which subsequently regulate autonomic outflow to peripheral organs and endocrine systems [19]. These hard-wired neural networks form the primary pathway for immediate SCN control over physiological rhythms.

Central Neural Circuitry

SCN efferent projections are largely confined to hypothalamic and midline thalamic regions, with the most prominent projections targeting the subparaventricular zone (SPZ) and dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMH) [19]. The SPZ serves as an intermediate relay station that amplifies and distributes SCN signals to other brain regions. Lesion studies indicate that the SPZ contributes significantly to the regulation of daily rhythms in sleep, locomotor activity, and body temperature [19].

The DMH, in turn, projects to multiple nuclei governing specific physiological functions:

- Ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO): Regulates sleep-wake cycles

- Lateral hypothalamic area (LHA): Coordinates energy balance and arousal

- Paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN): Modulates stress response and autonomic tone [19]

This multi-synaptic pathway allows the SCN to indirectly influence diverse functions including neuroendocrine secretion, autonomic nervous system activity, and behavior.

Autonomic Regulation of Peripheral Organs

The SCN regulates peripheral circadian clocks via autonomic nervous system outputs. SCN projections to the PVN initiate sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways that synchronize peripheral oscillators in organs such as the liver, heart, and pancreas [18]. This neural synchronization enables rapid, tissue-specific regulation of circadian physiology without relying on systemic cues.

The adrenal gland exemplifies this neural control mechanism. The SCN influences glucocorticoid secretion not only through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis but also via direct innervation through the splanchnic nerve, which modulates adrenal sensitivity to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) [6] [20]. This autonomic connection transmits photic information directly from the SCN to the adrenal cortex, contributing to the robust circadian rhythm of glucocorticoid release [6].

Endocrine Output Pathways from the SCN

In addition to direct neural control, the SCN regulates systemic synchronizers through neuroendocrine pathways that rhythmically release hormones into circulation. These hormonal signals serve as potent zeitgebers for peripheral clocks throughout the body.

Glucocorticoid Rhythms

Circulating glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rodents) exhibit robust circadian rhythms that are critically dependent on SCN regulation. The SCN generates this rhythm through three distinct mechanisms:

- Circadian control of the HPA axis via arginine-vasopressin (AVP) projections from the SCN to the PVN, generating rhythmic firing patterns in downstream regions [6]

- Autonomic regulation of adrenal sensitivity via the splanchnic nerve, which modulates adrenal responsiveness to ACTH [6] [20]

- Gating of adrenal sensitivity by the intrinsic adrenal circadian clock, which further contributes to robust glucocorticoid rhythm generation [6]

Glucocorticoids function as systemic synchronizers by binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) that directly regulate clock gene expression, particularly Per1 and Per2, in peripheral tissues [6]. Through this mechanism, the daily glucocorticoid rhythm entrains peripheral clocks throughout the body.

Table 2: Endocrine Synchronizers Regulated by the SCN

| Hormone | Rhythm Characteristics | Primary Targets | Function as Zeitgeber |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids | Peak before active phase; ultradian pulsatility | Liver, heart, adipose, muscle | Resets peripheral clocks via GREs in clock genes |

| Melatonin | Nocturnal peak; duration encodes night length | SCN, pituitary, immune cells | Provides feedback to SCN; synchronizes peripheral tissues |

| Vasopressin | Diurnal rhythm from SCN neurons | SPZ, DMH, PVN | Regulates HPA axis; coordinates neural outputs |

| Prokineticin 2 | Highest expression during subjective night | DMH, LHA | Reduces locomotor activity; regulates circadian behavior |

Melatonin Rhythms

Melatonin secretion from the pineal gland represents another key endocrine output of the SCN. The SCN generates the melatonin rhythm through two regulatory signals:

- A clock-coupled signal that restricts melatonin synthesis to the nocturnal phase

- An inhibitory signal that transmits incidental nighttime light exposure to acutely suppress melatonin production [6]

Melatonin acts as both a rhythm driver and zeitgeber by:

- Providing feedback to the SCN via MT1 and MT2 receptors to fine-tune circadian phase

- Synchronizing peripheral clocks in various tissues through receptor-mediated signaling pathways

- Refining the amplitude and robustness of circadian rhythms throughout the body [6]

The duration of melatonin secretion encodes night length, providing a seasonal timing signal that regulates photoperiodic responses in mammals.

Other Hormonal Outputs

The SCN also regulates the circadian rhythms of several other hormones through direct and indirect pathways:

- Growth hormone: Secretion peaks at sleep onset and correlates with renin levels [6]

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone: Exhibits a circadian rhythm that is influenced by sleep-wake state

- Metabolic hormones: Including leptin, adiponectin, ghrelin, insulin, and glucagon, whose rhythms are influenced by both circadian timing and feeding behavior [6]

These endocrine rhythms collectively coordinate temporal organization across metabolic, immune, and cardiovascular systems.

Experimental Protocols for Studying SCN Output Pathways

Multi-Modal Data Acquisition and Synchronization

Investigating SCN output pathways requires precise temporal alignment of data from multiple recording modalities. The Syntalos platform provides an open-source solution for synchronized multi-modal data acquisition [21].

Protocol: Synchronized Neural and Endocrine Recording

- System Setup: Configure Syntalos with modules for electrophysiology (Intan RHX), calcium imaging (UCLA Miniscope), video tracking, and endocrine sampling apparatus

- Timing Synchronization: Implement continuous timestamp alignment to a global master clock with statistical analysis and correction of individual device timestamp divergences

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously record neuronal activity (spike patterns, calcium dynamics), behavioral parameters (locomotor activity, feeding), and endocrine samples (blood collection for hormone assay)

- Closed-Loop Interventions: Program Arduino-based I/O interfaces for state-dependent sampling with 2-6 ms latency

- Data Integration: Store all data in structured formats with unified timestamps for subsequent correlation analysis

Validation: Temporal misalignment >1 ms/sec between high-speed video and electrophysiological signals can reduce stimulus classification accuracy from 100% to chance levels in sensory discrimination tasks, highlighting the critical importance of precise synchronization [21].

SCN Neural Circuit Mapping

Protocol: Anterograde and Retrograde Tract Tracing

- Stereotaxic Surgery: Inject recombinant AAV-expressing fluorescent reporters (e.g., GFP) under cell-specific promoters into the SCN of anesthetized mice

- Neural Pathway Visualization: Process brain sections for immunohistochemistry to identify projection targets (SPZ, DMH, PVN)

- Functional Connectivity Assessment: Combine tract tracing with immediate early gene (c-Fos) expression during specific circadian phases

- Circuit Manipulation: Employ optogenetic or chemogenetic approaches to selectively activate or inhibit SCN output pathways

- Output Measurement: Quantify changes in peripheral gene expression, hormone levels, and physiological parameters

Endocrine Rhythm Characterization

Protocol: Hormonal Sampling and Analysis

- Serial Blood Collection: Implement automated sampling systems or manual collection at 2-4 hour intervals across the 24-hour cycle

- Hormone Assay: Utilize ELISA or RIA for melatonin, corticosterone, and other hormones of interest

- Rhythm Analysis: Apply Cosinor analysis or similar mathematical models to determine rhythm parameters (mesor, amplitude, acrophase)

- Peripheral Clock Assessment: Measure clock gene expression rhythms (Per2::Luciferase reporters) in peripheral tissues

- Intervention Studies: Test effects of SCN lesions, timed feeding, or light exposure manipulations on endocrine rhythms

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

SCN Neural Output Pathway

SCN Neural Output Pathway: This diagram illustrates the multi-synaptic neural pathways through which the SCN regulates physiological and behavioral rhythms. The SCN projects primarily to hypothalamic nuclei (SPZ, DMH, PVN), which then relay signals to regulatory centers controlling sleep, feeding, and neuroendocrine function.

Endocrine Synchronization of Peripheral Clocks

Endocrine Synchronization Pathway: This diagram shows the endocrine pathways through which the SCN regulates melatonin and glucocorticoid secretion, which in turn synchronize peripheral clocks in tissues throughout the body. Dashed lines represent hormonal actions on peripheral tissues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying SCN Output Pathways

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Syntalos Platform | Multi-modal data acquisition and synchronization | Simultaneous recording of electrophysiology, imaging, and behavior with precise temporal alignment [21] |

| AAV Vectors | Anterograde and retrograde neural tracing | Mapping SCN neural connectivity to SPZ, DMH, and PVN targets |

| Per2::Luciferase Reporters | Real-time monitoring of circadian rhythms in tissues | Assessing peripheral clock synchronization by SCN outputs |

| Optogenetic Tools (Channelrhodopsin, Archaerhodopsin) | Cell-specific activation/inhibition of SCN neurons | Testing necessity and sufficiency of specific SCN output pathways |

| Chemogenetic Tools (DREADDs) | Remote control of neuronal activity | Chronic manipulation of SCN circuits without implanted hardware |

| ELISA/RIA Kits | Hormone quantification | Measuring circadian rhythms in melatonin, glucocorticoids |

| c-Fos Antibodies | Neural activity mapping | Identifying recently activated neurons in output regions |

| Clock Gene Antibodies | Immunohistochemistry and Western blotting | Localizing and quantifying clock protein expression |

Implications for Drug Development and Chronotherapy

Understanding SCN output pathways has profound implications for pharmaceutical development and therapeutic optimization. Chronotherapy—the timing of drug administration to align with biological rhythms—can significantly enhance efficacy and reduce adverse effects [18].

Cardiovascular Chronotherapy

The circadian regulation of cardiovascular function creates time-dependent windows of vulnerability and therapeutic opportunity:

- Morning surge in blood pressure and sympathetic tone coincides with peak incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke [18] [22]

- Coagulation factors like plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) peak in the early morning, creating a prothrombotic state [18]

- Antihypertensive medications show improved efficacy when timed to target morning blood pressure surge [18]

- Antiplatelet agents may provide superior protection when aligned with circadian peaks in platelet aggregability [18]

Endocrine-Targeted Therapeutics

The endocrine outputs of the SCN provide opportunities for novel therapeutic approaches:

- Melatonin agonists (ramelteon, agomelatine) can reset circadian phase in sleep disorders and depression [6]

- Glucocorticoid receptor modulators timed to circadian rhythms may improve metabolic outcomes while minimizing side effects [6]

- REV-ERB agonists show promise for enhancing circadian amplitude and treating metabolic disorders [18]

Experimental Chronopharmacology Protocols

Protocol: Drug Timing Studies

- Rhythm Characterization: First establish circadian rhythms in target pathways (enzyme activity, receptor expression, metabolic processes)

- Dosing Time Optimization: Administer drug candidates at multiple circadian times using controlled lighting conditions

- PK/PD Analysis: Compare pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics across circadian phases

- Mechanistic Studies: Investigate molecular clock components regulating drug target rhythms

- Therapeutic Optimization: Identify optimal dosing schedules that align with biological rhythms for maximum efficacy and minimum toxicity

The SCN functions as the master circadian coordinator through precisely regulated neural and endocrine output pathways. These systemic synchronizers maintain temporal alignment across brain regions and peripheral organs, optimizing physiological function. Disruption of these pathways—through genetic mutations, environmental misalignment (shift work, jet lag), or aging—contributes to numerous pathological conditions.

Future research should focus on:

- Developing more sophisticated models of multi-oscillator network interactions

- Identifying novel synchronizing factors that mediate SCN-peripheral communication

- Advancing chronotherapeutic approaches for circadian-related disorders

- Exploring personalized circadian medicine based on individual circadian phenotypes

The continued elucidation of SCN output mechanisms will provide critical insights for developing novel treatments that restore circadian alignment and promote optimal health throughout the lifespan.

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of three pivotal oscillating hormone systems—melatonin, glucocorticoids, and metabolic hormones—that govern circadian rhythmicity in mammalian physiology. We examine the molecular mechanisms, regulatory functions, and interdisciplinary connections of these hormonal oscillators within the framework of endocrine regulation of circadian rhythms. The content synthesizes current research on how these hormones synchronize central and peripheral clocks, their roles in maintaining temporal homeostasis, and the pathological consequences of circadian disruption. Targeted to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review integrates foundational knowledge with emerging therapeutic strategies that target circadian biology for metabolic, neurological, and sleep-related disorders.

Circadian rhythms are endogenous 24-hour oscillations in physiology, metabolism, and behavior that persist in the absence of external cues, allowing organisms to anticipate and adapt to daily environmental changes. These rhythms are generated and maintained by a hierarchical network of molecular clocks, with the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus serving as the central pacemaker that synchronizes peripheral oscillators in virtually all tissues and organs [23] [24]. The circadian system functions as a multistage processor that integrates environmental time cues (zeitgebers), primarily light-dark cycles, with internal metabolic signals to optimize the temporal organization of biological processes [23].

The molecular clockwork consists of interlocking transcription-translation feedback loops (TTFLs) involving core clock genes including CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, CRY, REV-ERB, and ROR. The CLOCK-BMAL1 heterodimer activates transcription of PER and CRY genes, whose protein products eventually repress CLOCK-BMAL1 activity, creating a approximately 24-hour oscillation [24]. This molecular oscillator regulates the rhythmic expression of thousands of genes in a tissue-specific manner, with nearly the entire primate genome showing daily rhythms in expression [24].

Endocrine systems serve as crucial mediators between the central circadian pacemaker and peripheral tissues, with several key hormones exhibiting robust circadian oscillations that coordinate physiological processes across the body. This whitpaper focuses on three fundamental oscillating hormone systems: melatonin, which conveys photic information; glucocorticoids, which integrate stress and metabolic responses; and metabolic hormones that coordinate energy homeostasis. Understanding the intricate regulation and functions of these hormonal oscillators provides critical insights for developing chronotherapeutic interventions for various disorders.

Melatonin: The Chronobiotic Regulator

Biosynthesis and Circadian Regulation

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is an indoleamine hormone primarily synthesized and secreted by the pineal gland during the dark phase in both diurnal and nocturnal animals [25] [26]. Its production follows a robust circadian rhythm controlled by the SCN through a multisynaptic pathway involving the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord, and superior cervical ganglion [26]. The synthesis begins with the uptake of the essential amino acid tryptophan, which is converted to serotonin through hydroxylation and decarboxylation. The key enzymatic steps in melatonin synthesis involve N-acetylation of serotonin by arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AA-NAT) followed by O-methylation by hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase (HIOMT) [26].

Light serves as the primary environmental cue that suppresses melatonin synthesis through retinal photoreceptors, particularly melanopsin-expressing intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) that project directly to the SCN [24] [25]. The SCN relays this light information to the pineal gland, resulting in inhibition of melatonin production during daylight hours. Conversely, the absence of light input disinhibits the SCN, allowing norepinephrine release from sympathetic nerve terminals that stimulates beta-adrenergic receptors on pinealocytes, triggering a cAMP-mediated signaling cascade that activates AA-NAT and dramatically increases melatonin synthesis [26]. This light-regulated mechanism creates the characteristic diurnal rhythm of melatonin secretion, with plasma levels typically low during the day, beginning to rise around 9-10 PM, peaking between 2-4 AM, and declining toward morning [25].

Table 1: Melatonin Oscillation Characteristics

| Parameter | Characteristics | Regulating Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Daily Peak Time | 2-4 AM | Suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) control, darkness |

| Amplitude Range | 3-10 times nighttime vs. daytime levels | Age, retinal light exposure, pineal health |

| Phase Marker | Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO) | Light exposure timing, circadian phase |

| Primary Zeitgeber | Light-dark cycle | Intensity, wavelength, duration of light exposure |

| Half-life | 20-50 minutes | Hepatic metabolism (CYP1A2, CYP2C19) |

| Secretory Pattern | Pulsatile | Sympathetic tone (norepinephrine) |

Receptor-Mediated and Non-Receptor-Mediated Mechanisms

Melatonin exerts its effects through both receptor-mediated and non-receptor-mediated mechanisms. There are two high-affinity G-protein-coupled membrane receptors identified in mammals: MT1 (Mel1a) and MT2 (Mel1b) [25] [26]. MT1 receptors primarily mediate sleep onset and vasoconstriction, while MT2 receptors are involved in phase-shifting circadian rhythms and regulating retinal and cardiovascular functions [25]. Both receptor subtypes are highly expressed in the SCN, with MT1 receptors inhibiting neuronal firing in response to melatonin and MT2 receptors mediating phase advances of circadian rhythms [23] [25]. Beyond the SCN, melatonin receptors are distributed throughout various tissues including the pituitary, retina, blood vessels, immune cells, and reproductive organs, indicating diverse physiological roles [26].

In addition to membrane receptors, melatonin acts through nuclear receptors, potentially including ROR/RZR retinoid orphan receptors, though this mechanism remains controversial [26]. Melatonin also exhibits non-receptor-mediated actions due to its amphiphilic nature, allowing it to cross cellular membranes easily and function as a broad-spectrum antioxidant and free radical scavenger [26]. It can directly neutralize reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, stimulate antioxidant enzymes (glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, catalase), and inhibit pro-oxidant enzymes, contributing to cytoprotection across various tissues [26]. Mitochondria represent a key target for melatonin's direct actions, where it helps maintain electron transport chain efficiency, reduce oxidative damage, and inhibit mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening [26].

Regulatory Functions in Sleep and Circadian Rhythms

Melatonin plays a fundamental role in regulating sleep and circadian rhythms through multiple interconnected mechanisms. As a "chronobiotic" molecule, it adjusts the timing of internal biological rhythms, primarily by phase-shifting the central circadian pacemaker in the SCN [23] [25]. Administration of melatonin during the biological day (when endogenous levels are low) typically induces phase advances, while evening administration can phase-delay rhythms, depending on the timing relative to the individual's circadian phase [25]. These phase-resetting properties form the basis for melatonin's therapeutic applications in circadian rhythm sleep disorders.

Melatonin also functions as a "hypnotic" agent that directly promotes sleep initiation and maintenance, particularly when administered during the day or in individuals with low endogenous production [23] [25]. The sleep-promoting effects emerge approximately 2 hours after intake, mirroring the physiological sequence at night, and are attributed to the attenuation of the SCN's wake-promoting signal rather than a sedative effect [23]. Functional MRI studies demonstrate that melatonin reduces activation in the precuneus region of the default mode network, correlating with increased subjective fatigue and sleep propensity [23]. This effect on brain activity patterns highlights melatonin's role in modulating neural circuits involved in arousal and consciousness.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Melatonin Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | Ramelteon (MT1/MT2 agonist), Luzindole (MT2 antagonist), S20928 (MT1 antagonist) | Receptor-specific pathway analysis, sleep architecture studies |

| Antibodies | Anti-AA-NAT, Anti-ASMT/HIOMT, Anti-MT1/MT2 receptors | Enzyme expression analysis, receptor localization, immunohistochemistry |

| ELISA/Kits | Salivary Melatonin ELISA, Plasma/Serum Melatonin RIA, Urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin EIA | Circadian phase assessment, rhythm amplitude measurement |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Beta-adrenergic blockers (propranolol), cAMP pathway modulators | Melatonin synthesis pathway analysis, sympathetic regulation studies |

| Cell Lines | Pinealocyte cultures, MT1/MT2 transfected HEK293 cells | Receptor signaling studies, high-throughput screening |

| Animal Models | C57BL/6J melatonin-proficient, Pinealectomized rodents, MT1/MT2 knockout mice | In vivo rhythm studies, receptor function analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Melatonin Research

Melatonin Phase Response Curve (PRC) Determination: To establish the phase-shifting effects of melatonin, collect blood or saliva samples every 30-60 minutes under dim light conditions (<10 lux) to assess dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) before and after melatonin administration at different circadian times. The protocol involves administering 0.5-5 mg melatonin at 6-8 different time points across the 24-hour cycle to healthy volunteers or animal subjects, with precise control of light exposure. Calculate phase shifts by comparing the timing of DLMO or other circadian markers (e.g., core body temperature minimum) before and after treatment [23] [25].

Melatonin Receptor Signaling Assay: Transfert MT1 or MT2 receptors into CHO or HEK293 cells and measure cAMP inhibition (for MT1) or phosphoinositide hydrolysis (for MT2) following melatonin stimulation. Pre-treat cells with pertussis toxin (100 ng/mL, 16-24 hours) to confirm Gi/o protein coupling. For competitive binding assays, incubate membrane preparations with [³H]-melatonin (0.1-5 nM) and increasing concentrations of test compounds for 60-120 minutes at 25-37°C, then separate bound and free ligand by rapid filtration through GF/B filters [25] [26].

Sleep Architecture Analysis with Melatonin: Administer extended-release melatonin (2 mg) or placebo to subjects (particularly aged ≥55 years) 30-60 minutes before bedtime for 4-6 weeks in a crossover design. Perform polysomnography (PSG) recordings including electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculography (EOG), and electromyography (EMG) to assess sleep latency, wake after sleep onset (WASO), total sleep time, and sleep stage distribution (N1, N2, N3, REM). Compare power spectral analysis of EEG frequencies, particularly in the delta (0.5-4 Hz) range, to evaluate sleep intensity [23] [25].

Glucocorticoids: The Stress-Responsive Oscillators

HPA Axis Dynamics and Circadian Regulation

Glucocorticoids (primarily cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rodents) are steroid hormones produced in the adrenal cortex that exhibit a robust circadian rhythm essential for metabolic homeostasis and stress adaptation [27] [28]. The secretory activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis follows a distinct 24-hour pattern characterized by a nadir around midnight, an abrupt increase 2-3 hours after sleep onset, a peak approximately at waking (around 8-9 AM), and a progressive decline throughout the day [27] [28]. This circadian rhythm originates from the interaction between the SCN and the HPA axis, with vasopressin-containing SCN neurons projecting to corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) to impose circadian information onto HPA activity [28].

The HPA axis operates through a classic endocrine cascade: CRH released from the hypothalamus stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion from the anterior pituitary, which in turn triggers glucocorticoid production from the adrenal cortex [27]. Glucocorticoids exert negative feedback at multiple levels (hypothalamus, pituitary, hippocampus) to regulate their own secretion, maintaining appropriate circulating levels and preventing excessive activation [27] [29]. The circadian rhythm of glucocorticoid secretion is modulated by the sleep-wake cycle, with sleep onset potentiating the declining phase of cortisol and awakening contributing to the morning peak [28].

Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid Signaling

Glucocorticoids exert their effects primarily through the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a ligand-activated transcription factor belonging to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily [29]. The GR consists of several functional domains: an N-terminal transactivation domain (AF1), a central DNA-binding domain (DBD) containing two zinc fingers, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) with a second transactivation function (AF2) [29]. In the absence of ligand, the GR resides in the cytoplasm as part of a multiprotein complex containing heat shock proteins (Hsp90, Hsp70) and immunophilins. Upon glucocorticoid binding, the receptor undergoes conformational changes, dissociates from chaperone proteins, homodimerizes, and translocates to the nucleus where it regulates gene expression through several mechanisms [27] [29].

The classical mechanism of GR action involves direct binding to glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) in the promoter regions of target genes, leading to transactivation or transrepression depending on the sequence context and cofactor recruitment [27] [29]. Negative GREs (nGREs) mediate direct repression of gene transcription. Additionally, GR can modulate gene expression without direct DNA binding through protein-protein interactions with other transcription factors such as AP-1, NF-κB, and STATs (tethering mechanism), or by binding to composite elements together with other DNA-bound factors (composite mechanism) [29]. These diverse mechanisms allow glucocorticoids to regulate a wide range of physiological processes, with transrepression primarily mediating anti-inflammatory effects and transactivation responsible for metabolic effects [27].

Figure 1: Glucocorticoid Signaling Pathway - This diagram illustrates the HPA axis activation, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) transformation, and subsequent genomic regulation through transactivation and transrepression mechanisms.

Circadian Integration and Systemic Effects

Glucocorticoids serve as key systemic synchronizers that help coordinate circadian rhythms throughout the body. The circulating glucocorticoid rhythm not only reflects SCN control but also participates in entraining peripheral clocks in various tissues including liver, muscle, and adipose tissue [28] [29]. This synchronizing function occurs through GR-mediated regulation of core clock gene expression, particularly Per1 and Per2, in peripheral tissues. The importance of this glucocorticoid-mediated entrainment becomes evident in shift work and jet lag scenarios, where misalignment between the central SCN clock and peripheral oscillators can disrupt metabolic homeostasis [28] [24].

The metabolic effects of glucocorticoids are extensive and include stimulation of gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and lipolysis while antagonizing insulin action [27]. These actions mobilize energy substrates during the active phase (wakefulness for diurnal species) to meet metabolic demands. Glucocorticoids increase blood glucose levels by promoting hepatic gluconeogenesis through induction of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase expression, while simultaneously decreasing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues by downregulating GLUT4 transporters [27]. In adipose tissue, glucocorticoids activate hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), increasing free fatty acid availability for beta-oxidation [27]. Chronic glucocorticoid excess leads to characteristic metabolic alterations including muscle wasting, skin thinning, central fat redistribution (moon face, buffalo hump), and hyperglycemia [27].

Table 3: Glucocorticoid Oscillation Characteristics

| Parameter | Characteristics | Regulating Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Daily Peak Time | ~8-9 AM | SCN regulation, wake time, HPA axis activity |

| Amplitude | 5-10 times morning peak vs. nighttime nadir | Stress, sleep quality, circadian alignment |

| Nadir Timing | Between midnight-4 AM | Sleep consolidation, HPA axis quiescence |

| Primary Regulator | HPA axis | SCN input, stress, negative feedback |

| Half-life | 60-90 minutes | Hepatic metabolism, renal excretion |

| Ultradian Pattern | Pulsatile (~hourly) | Hypothalamic pulse generator |

Experimental Protocols for Glucocorticoid Research

Diurnal Cortisol Rhythm Assessment: Collect saliva or blood samples at multiple time points across the 24-hour cycle (e.g., upon waking, 30 minutes post-waking, midday, late afternoon, bedtime) for 1-2 consecutive days. For saliva sampling, instruct participants not to eat, drink, or brush teeth 30 minutes before collection. For plasma measurements, use an indwelling catheter to minimize stress from repeated venipuncture. Assay samples using ELISA, RIA, or LC-MS/MS with appropriate quality controls. Calculate the cortisol awakening response (CAR) as the difference between waking and 30-minute post-waking values, and the diurnal slope as the rate of decline from peak to nadir [27] [28].

GR Nuclear Translocation Assay: Culture cells expressing GR-GFP fusion protein in chambered coverslips. Treat with dexamethasone (100 nM) or vehicle for various durations (15 minutes to 2 hours). Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, counterstain nuclei with DAPI, and visualize using confocal microscopy. Quantify nuclear translocation by calculating the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity using image analysis software. For higher throughput, use a cell line stably expressing GR-luciferase and measure nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions separately using a luminometer [29].

Glucocorticoid Sensitivity Testing: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from fresh blood samples using density gradient centrifugation. Culture cells in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% charcoal-stripped FCS. Treat with increasing concentrations of dexamethasone (10^-10 to 10^-6 M) for 1 hour prior to stimulation with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 24 hours. Measure lymphocyte proliferation using [³H]-thymidine incorporation or cytokine production (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) by ELISA. Calculate IC50 values to determine glucocorticoid sensitivity [29].

Metabolic Hormones: Integrating Energy Homeostasis

Growth Hormone and Prolactin Rhythms

Growth hormone (GH) and prolactin (PRL) exhibit distinct sleep-dependent rhythms that coordinate metabolic processes and energy homeostasis. GH secretion demonstrates a strong association with slow-wave sleep (SWS), with a major secretory burst occurring approximately 90 minutes after sleep onset during the first SWS period [30]. This pulsatile release pattern is significantly diminished during sleep deprivation, indicating a crucial relationship between SWS and GH secretion [30]. The sleep-related GH surge mediates important anabolic functions including tissue repair, muscle development, and growth processes, highlighting the metabolic restoration that occurs during sleep.

Prolactin secretion follows a different pattern, characterized by increasing levels throughout the night with peak concentrations occurring during the early morning hours [30]. Unlike GH, prolactin rhythm is more closely tied to the sleep-wake cycle than to specific sleep stages, with secretion enhanced during sleep regardless of the time of day. This rhythm is regulated by complex interactions between hypothalamic dopamine (the primary prolactin-inhibiting factor), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and serotonin [30]. Beyond its classical role in lactation, prolactin influences various metabolic processes including pancreatic function, hepatic steatosis, and adipose tissue metabolism through receptors widely distributed in metabolic tissues [30].

Sex Steroid Oscillations

Testosterone (TT) in males exhibits a robust circadian rhythm characterized by increasing levels with prolonged sleep duration and peak levels in the early morning hours [30]. This rhythm is closely associated with REM sleep, with young men typically reaching peak levels during the first REM episode and maintaining elevated levels until awakening [30]. The tight coupling between REM sleep and testosterone secretion means that disruptions in sleep architecture, particularly reductions in REM sleep frequency or efficiency, directly impact testosterone levels. Conversely, low testosterone levels can further disrupt sleep quality, creating a potential vicious cycle characterized by increased awakenings and decreased SWS [30].

Estradiol (E2), the primary estrogen during female reproductive years, demonstrates complex relationships with sleep architecture that vary across different populations and physiological states [30]. Estrogen appears to lessen the homeostatic sleep need, potentially through its actions on the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO), a key sleep-regulatory region. E2 attenuates the action of adenosine A2A receptors on the MnPO, resulting in increased arousal episodes and significant inhibition of NREM sleep, particularly during the dark phase in diurnal species [30]. These interactions between sex steroids and sleep regulation contribute to the gender differences observed in sleep architecture and the prevalence of sleep disorders.

Thyroid Axis Rhythms

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis exhibits complex circadian regulation that interacts with sleep-wake processes. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) demonstrates a distinct circadian rhythm characterized by a rise prior to sleep onset, reaching peak concentrations during the night, and declining upon morning awakening [30]. This rhythm is modulated by both circadian influences and sleep itself, with sleep deprivation resulting in enhanced and prolonged TSH secretion [30]. Interestingly, different types of sleep disruption produce distinct effects on the thyroid axis—REM sleep deprivation induces central hypothyroidism with decreased TSH secretion and reduced circulating thyroxine (T4) levels, while total sleep deprivation suppresses TRH secretion [30].

The interplay between thyroid hormones and sleep regulation represents a bidirectional relationship. Thyroid hormones influence sleep architecture, with hyperthyroidism typically associated with sleep fragmentation and reduced sleep efficiency, while hypothyroidism may contribute to excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue. Meanwhile, sleep disturbances can significantly impact thyroid axis function, potentially contributing to the metabolic consequences commonly observed in sleep disorders. These interconnected relationships highlight the importance of considering circadian and sleep-wake influences when assessing thyroid function and implementing thyroid-related therapies [30].

Table 4: Metabolic Hormone Oscillations and Sleep Relationships

| Hormone | Peak Secretion Time | Primary Sleep Relationship | Major Metabolic Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Hormone (GH) | First SWS period (N3) | Strongly linked to slow-wave sleep | Tissue repair, muscle development, growth mediation |

| Prolactin (PRL) | Early morning hours | Sleep-dependent (not stage-specific) | Lactation, reproduction, energy metabolism |

| Testosterone (TT) | Early morning | Associated with REM sleep | Sperm production, sexual characteristics, muscle mass |

| Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) | During night | Rise before sleep, decline after awakening | Metabolism, thermogenesis, growth, development |

| Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) | Varies by cycle | Positive correlation with sleep duration | Follicular growth, estrogen production, sperm production |

Interdisciplinary Connections and Therapeutic Implications

Bidirectional Relationships Between Sleep and Hormonal Systems

The relationships between sleep and hormonal systems are fundamentally bidirectional, with sleep architecture influencing hormonal secretion patterns and hormones reciprocally modulating sleep structure and quality. The HPA axis exemplifies this bidirectional relationship—sleep deprivation, sleep disruption, and circadian misalignment activate the HPA axis, leading to elevated cortisol levels that can further disrupt sleep architecture [28] [30]. This creates a potential vicious cycle wherein sleep loss begets HPA dysregulation which in turn perpetuates poor sleep. Specifically, sleep restriction to 4 hours per night for 6 consecutive nights results in increased cortisol levels in the afternoon and early evening, with a delayed onset of the quiescent period by approximately 1.5 hours [28].

Different sleep stages exert distinct influences on hormonal secretion. Slow-wave sleep (SWS) is associated with inhibition of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secretion, activation of the vagus nerve, promotion of growth hormone (GH) release, and reduction of cortisol levels, collectively contributing to improved glucose metabolism [30]. In contrast, REM sleep regulates testosterone secretion rhythms and activates the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in elevated blood pressure, disrupted insulin secretion, and increased diabetes risk [30]. The proportional distribution of sleep stages throughout the night therefore creates a complex temporal pattern of hormonal regulation that optimizes metabolic functioning when properly aligned with circadian phase.

Metabolic Consequences of Circadian Disruption

Circadian disruption, whether from shift work, jet lag, social jet lag, or genetic alterations in clock components, produces significant metabolic consequences that increase disease risk. Modern society poses two primary types of circadian challenge: extended light exposure at night that suppresses melatonin and delays sleep onset, and early waking demands that reduce sleep duration [24]. This misalignment between endogenous circadian rhythms and behavioral cycles disrupts the temporal coordination of metabolic processes, leading to impaired glucose tolerance, decreased insulin sensitivity, dyslipidemia, and increased adiposity [28] [24] [30].

The mechanisms underlying these metabolic consequences involve dysregulation across multiple hormonal systems. Circadian misalignment alters the normal rhythmicity of cortisol secretion, with shifted sleep-wake cycles causing profound disruptions in the 24-hour cortisol rhythm characterized by higher nadir values and altered acrophase timing [28]. Similarly, melatonin secretion is suppressed by light exposure at night, eliminating its important regulatory effects on insulin secretion and glucose metabolism [23] [26]. These hormonal disturbances, combined with mistimed feeding behavior, create a metabolic environment conducive to the development of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes [28] [24] [30].

Figure 2: Circadian Disruption Pathway - This diagram illustrates how modern lifestyle factors disrupt circadian rhythms, leading to hormonal dysregulation and increased metabolic disease risk through multiple interconnected pathways.

Chronotherapeutic Approaches

Chronotherapy represents a promising approach for optimizing treatment outcomes by aligning therapeutic interventions with biological rhythms. For circadian rhythm sleep disorders, strategically timed melatonin administration can help reset the central pacemaker and realign sleep-wake cycles with desired schedules [23] [25]. The phase-shifting effects of melatonin follow a phase-response curve (PRC) wherein administration during the biological afternoon/evening produces phase advances, while administration during the biological night/early morning causes phase delays [25]. This principle can be applied therapeutically for conditions like delayed sleep phase syndrome (advancing evening melatonin) or advanced sleep phase syndrome (delaying early morning melatonin).

The timing of medication administration for endocrine and metabolic disorders can significantly impact both efficacy and side effect profiles. For glucocorticoid therapies, morning administration typically produces less HPA axis suppression than evening dosing, as it more closely mimics the physiological cortisol rhythm [27] [29]. Similarly, the metabolic effects of many medications vary according to circadian timing—statins are often more effective when taken in the evening due to the nocturnal peak in cholesterol synthesis, while certain antihypertensive medications may be more beneficial when taken at bedtime [24]. These chronotherapeutic principles highlight the importance of considering biological timing in treatment regimen design.

The oscillating hormones melatonin, glucocorticoids, and metabolic hormones form an integrated network that coordinates circadian physiology and maintains metabolic homeostasis. These hormonal systems function as both outputs of the central circadian pacemaker and as regulatory inputs that fine-tune peripheral clocks throughout the body. Their complex interactions create a temporal organization of physiological processes that optimizes energy utilization, repair mechanisms, and adaptive responses to environmental challenges. Disruption of these hormonal oscillations through modern lifestyle factors, sleep disorders, or circadian misalignment contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of metabolic, cardiovascular, and neuropsychiatric disorders.