Chronopharmacology in Drug Development: Mitigating Medication Interference in Circadian Hormone Sampling

This article addresses the critical challenge of medication-induced circadian disruption in biomedical research and drug development.

Chronopharmacology in Drug Development: Mitigating Medication Interference in Circadian Hormone Sampling

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of medication-induced circadian disruption in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the foundational mechanisms by which therapeutics interfere with endocrine circadian rhythms, provides methodological frameworks for accurate hormone sampling in clinical trials, offers troubleshooting strategies for optimizing protocol design, and discusses validation techniques for distinguishing drug-induced effects from endogenous rhythms. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this comprehensive review synthesizes current chronobiological principles with practical applications to enhance data reliability, improve drug safety profiling, and advance personalized chronotherapy approaches.

The Circadian-Hormone Axis: Understanding Fundamental Interference Mechanisms

Core Principles of Circadian Clock Organization and Hormonal Regulation

Troubleshooting Guide: Circadian Hormone Sampling and Analysis

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when investigating circadian rhythms in hormonal systems, particularly in the context of medication interference studies.

FAQ: Pre-Analytical Phase

Q: My hormonal assay results, particularly for melatonin, show high variability between participants. What could be the cause?

- A: Uncontrolled light exposure is a primary culprit. Light is the most potent zeitgeber (time-giver) and can acutely suppress melatonin production [1]. Ensure participants are in dim light conditions for several hours before and during sample collection for melatonin assessment. The use of "Dim Light Melatonin Onset" (DLMO) protocols is the gold standard for phase determination [2].

Q: I am observing inconsistent cortisol rhythms in my cohort. What pre-analytical factors should I verify?

- A: Inconsistent rhythms can stem from poor control of wake-up times and the cortisol awakening response (CAR). Cortisol secretion has a strong circadian rhythm with its highest pulse around wake-up time [1]. Standardize wake-up times across study participants and document the exact time of each sample. Also, control for stress, as it can activate the HPA axis independently of the circadian clock.

Q: How can I account for the effects of investigational medications on core clock gene expression?

- A: Many drugs can directly or indirectly influence the molecular clock. When possible, analyze the 24-hour expression profile of core clock genes (e.g., ARNTL1, PER2, NR1D1) in the target tissue alongside hormone measurements [2]. This allows you to distinguish whether a drug alters hormonal rhythms by directly resetting the local tissue clock (a zeitgeber effect) or by affecting downstream hormonal pathways without changing the core clock phase (a rhythm driver or tuning effect) [1].

FAQ: Analytical and Interpretation Phase

Q: Blood sampling is invasive and limits frequency. What is a robust alternative for circadian phase assessment?

- A: Saliva is a validated, non-invasive biological material for circadian rhythm analysis [2]. It allows for high-frequency, at-home sampling and can be used to measure both hormonal levels (cortisol, melatonin) and core clock gene expression rhythms from the same sample, providing a multi-modal assessment of circadian phase [2].

Q: How many timepoints are needed to reliably determine a participant's circadian phase?

- A: While more timepoints provide a higher-resolution rhythm, studies have shown that protocols sampling at 3-4 time points per day over 2 consecutive days can yield robust and stable circadian profiles for core clock genes in saliva [2]. This balance between practical feasibility and data robustness is suitable for clinical applications.

Q: My data shows a disconnect between the central SCN clock phase and a peripheral hormone rhythm. Is this possible?

- A: Yes. While the SCN is the master pacemaker, peripheral clocks in organs like the liver, adrenal gland, and pineal gland can be reset by non-photic cues. The most potent cue is the feeding-fasting cycle [1] [3]. An investigational drug that alters meal timing or composition could therefore dissociate peripheral hormonal rhythms from the central light-entrained SCN rhythm.

Experimental Protocols for Circadian Hormone Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Circadian Phase via Salivary Biomarkers

This non-invasive protocol is ideal for human studies, especially those investigating medication effects on circadian timing.

- Participant Preparation: Instruct participants to maintain a consistent sleep-wake schedule for at least one week prior to sampling. During the sampling period, enforce dim light conditions (<10 lux) from 2 hours before the first sample until the end of the protocol.

- Sample Collection: Collect saliva samples at 3-4 pre-defined time points per day (e.g., upon waking, 30 minutes post-waking, afternoon, before bed) for 2 consecutive days. Use a standardized preservative like RNAprotect at a 1:1 ratio with saliva to stabilize RNA for gene expression analysis [2].

- Sample Processing:

- Centrifuge samples to separate cellular material from supernatant.

- Aliquot supernatant for hormone analysis (melatonin, cortisol) via ELISA or LC-MS.

- Extract total RNA from the cell pellet for gene expression analysis of core clock genes (e.g., ARNTL1, PER2, NR1D1) via qRT-PCR.

- Data Analysis: Determine the acrophase (time of peak) for each analyte. Correlate the acrophases of hormone levels and gene expression to understand the coupling between the local clock and hormonal output.

Protocol 2: Investigating Drug-Induced Circadian Disruption in Cell Models

This in vitro protocol helps determine if a medication directly interferes with the core molecular clockwork.

- Cell Culture and Synchronization: Culture cells containing a functional circadian clock (e.g., primary fibroblasts, engineered reporter cell lines). Synchronize the cellular clocks by treating with a high concentration of dexamethasone (100 nM) or serum shock for 2 hours [1].

- Drug Treatment: After synchronization, wash out the synchronizing agent and apply the investigational medication at physiologically relevant concentrations. Include vehicle-only controls.

- Sample Harvesting: Collect cell lysates every 4-6 hours over a period of at least 48 hours post-synchronization.

- Readouts:

- Gene Expression: Analyze mRNA levels of core clock genes (Bmal1, Per2, Rev-Erbα) via qRT-PCR.

- Protein Expression: Analyze oscillation of clock proteins (e.g., BMAL1, PER2) via western blotting or immunocytochemistry.

- Analysis: Compare the period, phase, and amplitude of oscillations between drug-treated and control cells to quantify the drug's impact on the core clock.

Quantitative Data on Circadian Hormonal Rhythms

The following table summarizes key hormonal rhythms relevant to medication interference studies.

Circadian Hormone Profiles and Their Regulation

| Hormone | Source Organ | Peak Phase (in Diurnal Humans) | Primary Regulator | Potential for Medication Interference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin | Pineal Gland | Night (during sleep) [1] | SCN via light input; acutely suppressed by light [1] | High (e.g., via beta-blockers, SSRIs) |

| Cortisol | Adrenal Cortex | Early morning, around wake-time (Cortisol Awakening Response) [1] | SCN (via HPA axis); adrenal clock gating [1] | High (e.g., via corticosteroids, anti-inflammatories) |

| Growth Hormone (GH) | Pituitary Gland | Early during sleep [1] | Sleep stage (non-REM sleep) [1] | Moderate (e.g., via GABA-ergic drugs) |

| Leptin | Adipose Tissue | Night [4] | Feeding-fasting cycle; sleep-wake cycle [4] | High (e.g., via drugs affecting appetite or metabolism) |

| Ghrelin | Stomach | Before meal times [4] | Feeding-fasting cycle [4] | High (e.g., via drugs affecting appetite or motility) |

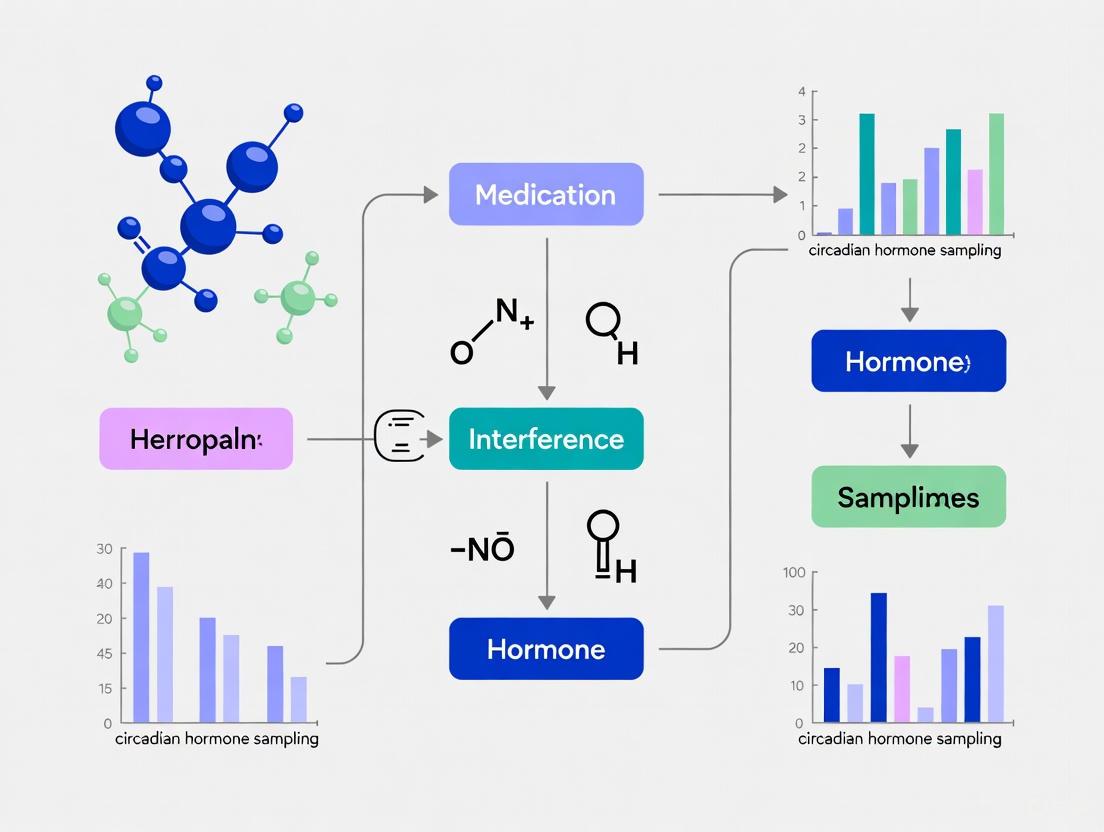

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Core Molecular Clock Feedback Loop

The following diagram illustrates the primary transcriptional-translational feedback loop of the mammalian circadian clock, which can be a direct target of pharmacological intervention.

Circadian Hormone Sampling Workflow

This diagram outlines the integrated experimental workflow for non-invasive circadian phase assessment in human subjects, suitable for drug study cohorts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Circadian Hormone Sampling Research

| Item | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Saliva Collection Kit (with RNA stabilizer) | Non-invasive collection and stabilization of RNA from saliva for gene expression studies. | High-frequency, at-home sampling of circadian phase in human subjects [2]. |

| Light Therapy Box / Metered Light Glasses | Provides controlled, bright light exposure for entrainment studies or as a standardized light stimulus. | Testing how a drug affects circadian phase shifts in response to light [5] [6]. |

| Melatonin ELISA or LC-MS Kit | Quantifies melatonin levels in saliva or plasma. Essential for determining DLMO, the gold standard phase marker. | Precisely measuring the timing of the circadian signal for sleep onset in medication trials [2]. |

| Cortisol ELISA Kit | Quantifies cortisol levels in saliva, serum, or plasma. | Assessing HPA axis rhythmicity and the impact of stress-related medications on circadian cortisol peaks [1] [2]. |

| qRT-PCR Assays for Core Clock Genes | Measures the expression rhythm of genes like ARNTL1 (BMAL1), PER2, and NR1D1 (REV-ERBα). | Determining if a drug acts directly on the molecular clockwork in peripheral tissues [2]. |

| Dexamethasone | A synthetic glucocorticoid used to synchronize cellular clocks in in vitro models. | Establishing a synchronized rhythm in fibroblast or cell-line cultures to test drug effects on period and phase [1]. |

Molecular Mechanisms of Medication Interference with Clock Gene Expression

The mammalian circadian clock is a cell-autonomous system governed by a network of core clock genes that form transcriptional-translational feedback loops (TTFLs) with a near-24-hour periodicity [7] [8]. The central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) coordinates rhythms throughout the body, but peripheral clocks exist in virtually all tissues [9]. These molecular clocks regulate the timing of physiological processes, including sleep-wake cycles, metabolism, hormone secretion, and immune function [8] [10].

Medications can interfere with clock gene expression through multiple molecular mechanisms: by directly binding to core clock components, altering post-translational modifications of clock proteins, affecting epigenetic regulation of clock genes, or disrupting the synchronizing signals that entrain circadian rhythms [11] [12]. Understanding these interference mechanisms is crucial for both predicting chronopharmacological interactions and developing novel circadian-targeted therapies.

Key Molecular Targets for Medication Interference

Core Clock Transcription Factors

The BMAL1-CLOCK heterodimer serves as the primary activator of circadian transcription, making it a prime target for pharmacological intervention [12].

Table 1: Core Clock Proteins as Direct Drug Targets

| Target Protein | Function in Circadian Clock | Known Pharmacological Modulators | Mechanism of Interference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMAL1 | Forms heterodimer with CLOCK; binds E-box elements to drive transcription of PER, CRY, REV-ERB, ROR genes | CCM (Core Circadian Modulator) [12] | Binds PAS-B domain, causing conformational changes that alter transcriptional activity |

| CLOCK | Heterodimerizes with BMAL1; histone acetyltransferase activity | CLK8 [12] | Binds bHLH segment, modulating transcriptional activity |

| REV-ERBα/β | Nuclear receptors that repress BMAL1 transcription | Synthetic ligands (e.g., SR9009, SR9011) [11] | Agonism enhances repression of BMAL1 transcription |

| RORα/γ | Nuclear receptors that activate BMAL1 transcription | Inverse agonists [11] | Suppress transcriptional activation of BMAL1 |

Recent research has demonstrated that the BMAL1 protein architecture is inherently configured to enable small molecule binding [12]. The development of CCM (Core Circadian Modulator), which targets the cavity in the PAS-B domain of BMAL1, represents a breakthrough in directly targeting core clock components. CCM binding causes the cavity to expand, leading to conformational changes in the PAS-B domain and altering BMAL1's function as a transcription factor [12].

Post-Translational Regulation Machinery

Casein kinase 1δ/ε (CK1δ/ε) regulates the stability and nuclear localization of PER proteins through phosphorylation [11] [8]. CK1δ/ε-mediated phosphorylation marks PER proteins for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system [11]. The F-Box proteins FBXL3 and FBXL21 target CRY proteins for proteasomal turnover [7] [8]. Mutations in human CK1δ (T44A) and PER2 (S662G) have been linked to Familial Advanced Sleep Phase Disorder (FASPD), highlighting the clinical importance of this regulatory mechanism [8].

Recent research has also identified SUMOylation as a novel layer of circadian regulation. SUMO modification of BMAL1 can enhance its transcriptional activation, while excessive SUMOylation promotes degradation through crosstalk with ubiquitination pathways [11]. SUMOylation of CLOCK influences its nuclear localization and stability, thereby fine-tuning circadian oscillations [11].

Figure 1: Core Circadian Clock Mechanism and Pharmacological Intervention Points. The diagram illustrates the transcriptional-translational feedback loop with key targets for medication interference.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Medication Interference

Protocol 1: Measuring Circadian Gene Expression in Peripheral Clocks

Objective: To evaluate the effects of test compounds on circadian gene expression rhythms in peripheral tissues or cultured cells.

Materials:

- CD14+ monocytes or other relevant cell types [13]

- RNA isolation kit (e.g., NucleoSpin RNA, Mini Kit) [13]

- Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) system

- Primers for core clock genes (PER1, PER2, PER3, NR1D1, NR1D2, CRY1, BMAL1, CLOCK) [13]

- Cell culture equipment and synchronization agents (dexamethasone, forskolin)

Methodology:

- Cell Isolation and Synchronization: Isolate CD14+ monocytes from whole blood using CD14+ microbeads and AutoMACS Pro separator [13]. Synchronize cells using 100 nM dexamethasone or 10 μM forskolin for 2 hours.

- Compound Treatment: Apply test compounds at various concentrations immediately after synchronization. Include vehicle controls.

- Time-Series Sampling: Collect samples every 4-6 hours over a 48-hour period. For human studies, multiple sampling timepoints are critical as single timepoint measurements may not detect phase shifts [13].

- RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Extract total RNA following manufacturer protocols. Assess RNA quality and concentration using spectrophotometry.

- RT-qPCR Analysis: Perform reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR using validated primer sets for core clock genes. Normalize to reference genes (GAPDH, ACTB).

- Data Analysis: Calculate relative expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method. Analyze rhythmic parameters (period, amplitude, phase) using specialized software (e.g., BioDare2, CircaCompare).

Troubleshooting: If rhythms are dampened quickly, consider lower compound concentrations or different application timing relative to synchronization.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening for BMAL1-Binding Compounds

Objective: To identify and characterize compounds that directly bind to core clock proteins.

Materials:

- Recombinant human BMAL1(PASB) protein [12]

- Fragment libraries for screening

- Protein thermal shift (PTS) assay reagents [12]

- Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) system

- Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) system

- Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) reagents

Methodology:

- Primary Screening: Use PTS assays to screen fragment libraries for compounds that stabilize BMAL1(PASB). Measure melting temperature (Tm) shifts ≥2°C as initial hits [12].

- Binding Affinity Determination: Confirm direct binding of hits using ITC and SPR. For CCM, Kd values of 1.99±0.38 μM (ITC) and 4 μM (SPR) were observed [12].

- Cellular Target Engagement: Validate binding in cellular contexts using CETSA with HiBiT-tagged BMAL1(PASB). CCM showed EC50 of 10.3 μM in cells [12].

- Selectivity Assessment: Evaluate binding selectivity against related PAS domains (BMAL2, ARNT, ARNT2) using CETSA [12].

- Functional Characterization: Assess effects on circadian oscillations using PER2::Luc reporter systems in U2OS cells. CCM induced dose-dependent alterations in PER2-Luc rhythms [12].

Troubleshooting: If cellular activity doesn't match biochemical binding affinity, check compound permeability and metabolic stability.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why don't we observe consistent clock gene expression changes in our human study samples?

Answer: Clock gene expression oscillates throughout the day, so single timepoint measurements may miss significant effects. Recent research demonstrates that individuals with early and late chronotypes may show similar gene expression at 7 a.m., despite having different circadian phases [13]. This suggests that:

- Multiple sampling timepoints are essential for detecting phase shifts or amplitude changes

- Chronotype assessment should be incorporated into study design using validated questionnaires (MCTQ, MEQ)

- Cell-type specific effects must be considered - analyze specific immune cell populations separately when possible

Solution: Implement a serial sampling design with at least 4 timepoints over 24 hours, stratify analysis by chronotype, and use cosinor analysis to detect rhythm parameter changes.

FAQ 2: How can we distinguish direct clock gene targeting from indirect effects?

Answer: Many medications affect circadian rhythms indirectly through neurotransmitter systems (melatonin, serotonin, GABA, dopamine) or metabolic pathways [11]. To establish direct mechanisms:

- Use in vitro binding assays (ITC, SPR) with recombinant clock proteins

- Perform cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) to demonstrate target engagement in living cells

- Test effects in genetic knockouts - if a compound requires specific clock genes for its effects, it likely acts directly on the clock machinery

- Evaluate phase-response curves - direct clock targets typically produce characteristic phase-dependent effects

Solution: Implement a tiered approach starting with binding assays, followed by target engagement studies, and finally functional assays in genetically modified systems.

FAQ 3: Our test compound affects circadian behavior in mice but not in cellular models. What could explain this discrepancy?

Answer: This common issue can arise from several factors:

- Metabolic activation: The compound may require metabolic conversion not occurring in cell culture

- Multi-tissue integration: Circadian behaviors emerge from SCN-peripheral clock interactions absent in isolated cells

- Neurohormonal pathways: The compound might act indirectly via glucocorticoid, melatonin, or autonomic signaling

- Concentration differences: Tissue distribution may result in different effective concentrations

Solution: Test metabolites in cellular assays, measure compound concentrations in brain tissue, use SCN slice cultures or organoid models that preserve tissue organization, and assess neuroendocrine markers.

Figure 2: Troubleshooting Workflow for Medication Interference Studies. This decision tree helps diagnose common experimental challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Studying Medication Interference with Clock Genes

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specific Application | Key Features | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| U2OS PER2::Luc cells | Reporter assay for circadian oscillations [12] | Stable PER2-promoter driven luciferase expression; robust rhythms | Requires serum shock or dexamethasone synchronization; measure bioluminescence for 5+ days |

| Recombinant BMAL1(PASB) | Direct binding studies [12] | Isolated PAS-B domain for structural and binding studies | May not fully recapitulate full-length protein behavior in cells |

| CEMs (Circadian Expression Microarrays) | Transcriptome-wide profiling of circadian gene expression [8] | Capture cycling transcripts beyond core clock genes | Requires 4+ timepoints over 48 hours for reliable rhythm detection |

| CD14+ monocytes | Human peripheral clock studies [13] | Accessible human peripheral clock model; relevant for immune-related drug effects | Expression levels vary by chronotype and sampling time; requires immediate processing |

| Synthetic REV-ERB ligands | Positive control for nuclear receptor targeting [11] | Well-characterized circadian period and phase effects | Can produce off-target effects at high concentrations |

| CK1δ/ε inhibitors | Positive control for post-translational regulation [8] | Modulate PER stability and degradation | Can affect multiple cellular pathways beyond circadian regulation |

Advanced Methodologies and Emerging Technologies

Nanomaterial-Enabled Drug Delivery for Circadian Medicine

Recent advances in nanotechnology offer innovative approaches for targeting circadian clocks. Various nanomaterials, including liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and mesoporous silica nanoparticles, enable sustained, targeted delivery of chronobiotics [10]. These systems address key challenges in circadian medicine:

- Temporal targeting: Programmed release at specific circadian times

- Tissue specificity: Functionalized nanoparticles can target specific peripheral clocks

- Combination therapy: Co-delivery of multiple compounds targeting different clock components

Smart drug delivery systems (SDDSs) that respond to physiological cues (temperature, pH, enzyme activity) represent a promising frontier for circadian medicine [10]. These systems could automatically deliver anti-inflammatory medications before daily inflammation peaks, as demonstrated in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis using genetically engineered stem cell implants [14].

Chronogenetic Approaches

The emerging field of "chronogenetics" involves engineering cells to respond to circadian signals for therapeutic purposes. Recent work has demonstrated that tissue implants incorporating genetically engineered stem cells can automatically deliver anti-inflammatory medications in response to circadian signals [14]. These implants effectively treated inflammatory flare-ups for up to a month in mice and rapidly resynchronized when the sleep schedule was reversed [14].

Single-Cell Circadian Analysis

Traditional circadian experiments measure population-level rhythms, potentially masking important cell-to-cell heterogeneity. Emerging single-cell technologies enable:

- Detection of circadian phase distributions in heterogeneous cell populations

- Identification of rare cell states with altered circadian parameters

- Characterization of circadian gene expression noise

These approaches are particularly valuable for understanding how medications might selectively affect specific subpopulations of cells within tissues.

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Quantitative Analysis of Circadian Parameters

When assessing medication interference with clock genes, quantify these key parameters:

- Period: The duration of one complete cycle (typically near 24 hours)

- Amplitude: The peak-to-trough difference in expression levels

- Phase: The timing of expression peaks relative to a reference point

- Damping rate: The rate at which rhythms diminish over time in constant conditions

Table 3: Statistical Methods for Analyzing Circadian Drug Effects

| Analysis Method | Application | Software Tools | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cosinor Analysis | Detecting rhythmicity in time-series data [13] | Cosinor, CircaCompare | Significant rhythm detected when p < 0.05 for cosine fit |

| JTK_CYCLE | Non-parametric rhythm detection | MetaCycle, BioDare2 | Robust to outliers; appropriate for noisy data |

| Oscillator Models | Modeling complex interactions between clock components | BioDare2, CellWare | Can predict effects of perturbations on system dynamics |

| Principal Component Analysis | Identifying patterns in high-dimensional circadian data | R, Python | Reveals compound-specific signatures of clock interference |

Integration with Omics Data

Modern circadian studies increasingly incorporate multiple data types:

- Transcriptomics: RNA-seq across multiple timepoints

- Proteomics: Assessment of clock protein abundance and modifications

- Phosphoproteomics: Analysis of rhythmic phosphorylation events

- Metabolomics: Measurement of circadian metabolites

Integrative analysis can reveal how medication interference at the clock gene level propagates through downstream regulatory networks to affect physiological outputs.

Impact of Drug Timing (Chronopharmacology) on Endocrine Rhythm Phase and Amplitude

Core Concepts in Chronopharmacology and Endocrine Rhythms

What are the fundamental principles of chronopharmacology that I must understand for endocrine research? Chronopharmacology is the study of how the effects of drugs vary with biological timing and endogenous periodicities, primarily the circadian rhythm. It is divided into two main areas: chronopharmacokinetics (how timing affects drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) and chronopharmacodynamics (how timing affects a drug's biochemical and physiological effects on the body) [15]. The endocrine system is under the control of central and peripheral circadian clocks, and its rhythmic secretions are influenced by both endogenous and environmental factors. Administering a drug can disrupt this delicate chrono-organization, altering the phase (timing of peaks/troughs) and amplitude (strength of oscillation) of hormonal rhythms, which is a critical source of interference in circadian hormone sampling research [16].

How is the circadian clock system hierarchically organized? The system is organized as a hierarchical network [17]:

- Master Clock: Located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. It is entrained primarily by the light-dark cycle and generates self-sustaining circadian rhythms [15] [18].

- Peripheral Clocks: Found in most cells throughout the body, including endocrine glands and target tissues. These are synchronized by the SCN through various signals, including autonomic nervous system output, hormonal rhythms (e.g., glucocorticoids, melatonin), and behavioral rhythms (e.g., feeding-fasting cycles) [17] [19]. Under normal conditions, these clocks are in phase harmony, but external perturbations like shift work or mistimed drug administration can cause internal desynchronization [17].

What is the molecular mechanism of the circadian clock? The core mechanism is a transcriptional-translational feedback loop involving key clock genes and proteins [17] [20] [19]:

- Activation: The CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins form a heterodimer that binds to E-box elements in the DNA, promoting the transcription of Period (Per) and Cryptochrome (Cry) genes.

- Repression: PER and CRY proteins accumulate, multimerize, and translocate back to the nucleus to inhibit the CLOCK:BMAL1 complex, repressing their own transcription.

- Cycle Renewal: The degradation of PER and CRY proteins allows the cycle to begin anew, with a period of approximately 24 hours. Auxiliary feedback loops involving genes like Rev-Erbα further stabilize this core oscillator [17].

The diagram below illustrates this core molecular machinery.

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

FAQ: My hormone assay results are highly variable despite controlled conditions. Could drug timing be a factor? Yes, this is a classic sign of unaccounted-for chronopharmacological interference. Variability can arise from:

- Chronopharmacokinetics: The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of your drug may vary with circadian time. For example, gastric pH and motility, liver enzyme activity (e.g., cytochrome P450 family), and renal blood flow all exhibit circadian rhythms, leading to time-dependent differences in drug concentration at the target site [15] [21].

- Chronesthesy: This refers to rhythmic changes in the susceptibility of a target system (e.g., a hormone-producing cell) to a drug. This can be due to circadian oscillation in receptor number/conformation, secondary messengers, or downstream metabolic pathways, independent of drug pharmacokinetics [21].

- Troubleshooting Action: Standardize the time of drug administration across all experimental subjects and ensure it is documented relative to the light-dark cycle or other synchronizing cues (e.g., feeding time).

FAQ: I have confirmed a drug alters cortisol rhythm. How can I determine if it's a direct effect on the adrenal gland versus an effect on the central SCN clock? Disentangling central vs. peripheral effects is a common challenge. The following experimental workflow can help you systematically identify the site of action.

FAQ: My animal model shows a blunted amplitude for a hormone rhythm after chronic drug treatment. Is this reversible? The reversibility of rhythm disruption depends on the drug, dose, and treatment duration. Amplitude dampening suggests a weakening of the underlying oscillatory system [20]. To assess reversibility:

- Implement a Drug Washout Period: Cease drug administration and continue to monitor hormonal profiles over multiple cycles.

- Reinforce Zeitgebers: During the washout, ensure a strong and consistent light-dark cycle and control feeding times, as these are potent synchronizers for peripheral clocks [16].

- Evaluate Recovery: Compare the mesor (average level), amplitude, and phase of the hormone rhythm post-washout to pre-treatment baselines. Full recovery suggests transient disruption, while persistent blunting may indicate more profound clock dysfunction that may require active chronotherapeutic intervention to reset [16].

Quantitative Data & Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Circadian Rhythm Parameters for Key Hormones Monitoring these parameters is essential for quantifying drug-induced interference.

| Hormone | Phase (Acrophase) | Amplitude (Representative) | Key Regulator / Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | Early morning, around wake-time (in diurnal humans) [19] | Peak-to-trough variation of 5-10 μg/dL (approx.) | HPA Axis; SCN via AVP; adrenal clock gating [19] |

| Melatonin | Night-time (peaks ~2-4 AM in darkness) [19] | Can increase >10-fold from daytime baseline [19] | SCN (light-inhibited, dark-activated) [19] |

| Growth Hormone (GH) | Major pulse at sleep onset [19] | - | Sleep-stage dependent (non-REM sleep) [19] |

| Testosterone | Early morning peak [16] | - | Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis [16] |

Table 2: Examples of Drug Chronopharmacodynamics Affecting Endocrine Parameters This table provides documented examples of how timing affects drug action.

| Drug Class / Example | Administration Time | Observed Chronopharmacodynamic Effect | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statins (HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors) [15] [22] | Evening / Night | Increased efficacy in lowering cholesterol | Human clinical practice; cholesterol synthesis peaks at night. |

| Beta-Blocker (Propranolol) [21] | 8 AM - 2 PM | Greater reduction in heart rate | Human study; aligns with high daytime sympathetic tone. |

| Immunotherapy (anti-PD-1/PD-L1) [23] [22] | Morning | Improved patient outcomes | Clinical trials; linked to circadian entry of lymphocytes into tumors in the morning. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Drug Impact on Corticosterone Rhythm in Rodents

This protocol is designed to systematically evaluate how a novel compound affects the phase and amplitude of a key glucocorticoid rhythm.

1. Objective To determine the effects of chronic administration of Drug X on the phase, amplitude, and mesor of the circadian corticosterone rhythm in a murine model.

2. Materials

- Animals: Adult male/female C57BL/6 mice (n=8-12 per group).

- Equipment: Standard light-controlled housing, HPLC-MS/MS system or ELISA kit for corticosterone, automated blood sampling system or equipment for serial saphenous vein sampling.

- Reagents: Drug X and vehicle control.

3. Methodology

- Animal Housing and Synchronization: House mice under a strict 12-hour light/12-hour dark (LD 12:12) cycle for at least two weeks prior to experimentation. Provide food and water ad libitum.

- Experimental Groups:

- Group 1 (Control): Administer vehicle at ZT (Zeitgeber Time) 2.

- Group 2 (Drug A.M.): Administer Drug X at ZT 2.

- Group 3 (Drug P.M.): Administer Drug X at ZT 14.

- Note: ZT0 is lights-on, ZT12 is lights-off.

- Dosing and Sampling: Administer drugs intraperitoneally for 7 consecutive days. On day 8, collect blood samples (e.g., ~20 μL via saphenous vein) from each animal at 4-hour intervals across the 24-hour cycle (e.g., ZT0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20). Use a cross-sectional design (different animals at each time point) to avoid stress from repeated sampling.

- Hormone Measurement: Process blood samples to plasma and measure corticosterone levels using a validated ELISA or MS/MS method according to manufacturer protocols.

- Data Analysis:

- Cosinor Analysis: Fit the 24-hour corticosterone data for each group to a cosine curve using the formula:

C(t) = M + A*cos(2π(t-φ)/τ), whereMis the mesor,Ais the amplitude,φis the acrophase, andτis the period (fixed at 24 hours). - Statistics: Compare the mesor, amplitude, and acrophase between groups using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., one-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests).

- Cosinor Analysis: Fit the 24-hour corticosterone data for each group to a cosine curve using the formula:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Chrono-Endocrine Research

| Item | Function / Application in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosterone / Cortisol ELISA Kit | Quantifies glucocorticoid levels in serum/plasma to assess HPA axis rhythm. | A high-sensitivity kit is crucial for detecting low trough levels. |

| Melatonin ELISA Kit / RIA | Measures melatonin in plasma/saliva to assess rhythm phase and amplitude; a marker of SCN function. | Requires careful handling due to melatonin's light sensitivity. |

| Antibodies (for IHC/WB): anti-BMAL1, anti-PER2 | Visualizes and quantifies core clock protein expression and localization in tissues (e.g., SCN, liver, adrenal). | Phospho-specific antibodies can assess post-translational regulation. |

| Bmal1-dLuc Reporter Cell Line | Real-time monitoring of molecular clock function in live cells after drug treatment. | Allows for high-throughput screening of clock-modifying compounds. |

| RNA Isolation Kit (Trizol-based) | Extracts high-quality RNA from tissues for qPCR analysis of clock gene expression (e.g., Per2, Rev-Erbα). | Ensure RNase-free conditions for rhythmic gene expression studies. |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Quantifies rhythmic mRNA expression of clock-controlled genes (CCGs) in target endocrine tissues. | Use geometric mean of multiple housekeeping genes for stable normalization. |

This guide provides technical support for researchers investigating how common drug classes disrupt circadian hormone rhythms. It covers documented case studies, core experimental methodologies, and troubleshooting for common challenges in this field.

Core Disruption Mechanism: Many drugs interfere with the Transcriptional-Translational Feedback Loop (TTFL) of the core circadian clock [4]. This molecular clock, governed by genes like CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, and CRY, regulates the rhythmic release of hormones such as cortisol and melatonin [24] [4]. Drug-induced disruption can alter the timing, amplitude, and phase of these hormonal rhythms, complicating research and therapeutic outcomes.

The diagram below illustrates this core molecular circuitry and the points where drug classes are known to cause interference.

Documented Case Studies & Data

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from studies on how common drug classes disrupt circadian hormone profiles.

Table 1: Documented Circadian Hormone Disruption by Drug Class

| Drug Class | Specific Drug(s) | Documented Circadian Disruption & Key Findings | Magnitude of Effect / Key Metrics | Primary Research Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | Various (General class) | Alters expression of core clock genes (CLOCK, Bmal1, Per); linked to treatment-emergent circadian side effects [24]. | - CRY1, NPAS2: Assoc. with unipolar depression [24].- CLOCK, VIP: Assoc. with bipolar disorder [24]. | Genetic association studies (SNP analysis), postmortem brain transcriptome analysis [24]. |

| Cholesterol-Lowering Agents | Atorvastatin | Circadian metabolism by liver enzyme CYP3A4 leads to varying production of toxic metabolites depending on administration time [25]. | Toxicity of atorvastatin was found to be significantly higher at specific times of day [25]. | In vitro testing using engineered human liver models [25]. |

| Analgesics | Acetaminophen (Tylenol) | Metabolism by CYP3A4 and other enzymes follows a circadian rhythm, affecting the production of the toxic metabolite NAPQI [25]. | Production of NAPQI varied by up to 50% based on the time of drug administration [25]. | In vitro testing using engineered human liver models [25]. |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | Nifedipine GITS, Verapamil COER/CODAS | Bedtime dosing demonstrated enhanced efficacy on blood pressure control and reduced side effects compared to morning dosing [26]. | Bedtime dosing was "more effective" for 24-hour BP control, with a "greater reduction in nocturnal BP" in non-dippers [26]. | Multicenter, double-blind, randomized clinical trials [26]. |

| Immunosuppressants / Chemotherapeutics | (Theoretical for many) | Drug metabolism pathways (e.g., involving CYP3A4) are under circadian control, suggesting a widespread potential for time-dependent efficacy/toxicity [25]. | The enzyme CYP3A4 metabolizes ~50% of all drugs and shows a clear circadian cycle [25]. | Gene expression analysis in engineered human livers; >300 liver genes identified with circadian rhythms [25]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Circadian Phase in Human Subjects

This is the gold-standard method for establishing an individual's endogenous circadian phase in a clinical or research setting.

- Objective: To determine the timing of an individual's circadian pacemaker by measuring the Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO) [27].

- Equipment & Reagents:

- Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO) testing kit (saliva collection kits).

- Salivary melatonin enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or radioimmunoassay (RIA).

- Access to a -20°C freezer for sample storage.

- FedEx or equivalent courier service for sample transport to a CLIA-certified lab [27].

- Pre-Test Conditions: Participants must avoid bright light for at least 2 hours prior to and throughout sample collection. They should refrain from using melatonin supplements for a period (consult lab guidelines) and avoid caffeine, alcohol, and brushing teeth immediately before sampling [27].

- Procedure:

- Begin collection in the early evening, approximately 4-6 hours before habitual bedtime.

- Collect 7 to 9 saliva samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 minutes).

- Participants must remain in dim light (< 10-30 lux) during the entire collection period.

- Samples are immediately frozen and shipped overnight on dry ice to the analytical lab.

- Data Analysis: The lab will provide a DLMO profile. The onset is typically defined as the time when melatonin concentration crosses a predetermined threshold (e.g., 3-4 pg/mL) or 2 standard deviations above the mean of the first three baseline samples [27].

Protocol 2: Longitudinal Monitoring of Sleep-Wake Patterns

This protocol is critical for diagnosing circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders like Non-24 and for monitoring the effects of drugs on rest-activity cycles.

- Objective: To objectively track sleep-wake patterns over extended periods (weeks to months) to identify circadian periodicity and disruptions [28].

- Equipment: Actigraph – a wrist-worn, accelerometer-based device.

- Procedure:

- The actigraph is worn continuously on the non-dominant wrist for a minimum of 14 days, though 4-7 weeks may be necessary to observe the drifting pattern of Non-24 [28].

- Participants simultaneously maintain a sleep diary to record subjective sleep times, wake times, sleep quality, and daytime alertness. This diary is used to validate and calibrate the actigraphy data.

- Data Analysis:

- Actigraphy data is processed using specialized software to calculate sleep onset, offset, duration, and fragmentation.

- The data is plotted over time to visualize the sleep-wake cycle. A diagnosis of Non-24 is supported by a pattern where sleep onset and wake time progressively delay each day (e.g., by 1-2 hours), creating a cycle that rotates around the clock [28].

Protocol 3: Profiling Circadian Gene Expression in Models

This in vitro approach is used to mechanistically study how drugs directly interfere with the molecular clock.

- Objective: To quantify the rhythmic expression of core clock genes and clock-controlled genes (e.g., Bmal1, Per2, Cry1, CYP3A4) in response to drug treatment.

- Model System: Engineered human livers [25], primary cell cultures, or animal tissues.

- Synchronization: Cells or tissues must first be synchronized. This can be achieved with a pulse of a corticosteroid (e.g., dexamethasone) or by manipulating the serum concentration in the culture medium.

- Drug Treatment & Sampling:

- Apply the drug of interest at different circadian times (e.g., at the peak vs. trough of a target gene's expression).

- Collect samples (e.g., for RNA or protein extraction) at regular intervals (e.g., every 3-6 hours) over a period of at least 48 hours [25].

- Downstream Analysis:

- qRT-PCR: To measure mRNA expression levels of target genes.

- RNA-Seq: For an unbiased, genome-wide transcriptomic analysis to identify all cycling genes and affected pathways [25].

- Western Blot / Immunoassays: To confirm changes at the protein level (e.g., for metabolic enzymes like CYP3A4).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our clinical study results on a drug's effect on cortisol rhythm are inconsistent. What could be the cause? A: Inconsistencies often stem from uncontrolled biological variables.

- Cause 1: Unaccounted for Circadian Time. The effect of a drug can vary dramatically based on the circadian time of administration [26] [25]. Administering a drug at different times across your cohort can introduce significant noise.

- Troubleshooting: Standardize drug administration time for all participants relative to their DLMO or wake time. In animal studies, control for Zeitgeber Time (ZT).

- Cause 2: Underlying Circadian Phase Differences. Participants with advanced, delayed, or misaligned circadian phases will show different hormonal responses [27].

- Troubleshooting: Measure and account for the baseline circadian phase (e.g., via DLMO) of each subject before starting the drug intervention.

Q2: We suspect our drug candidate causes circadian disruption in our animal model. What is the first experiment to confirm this? A: Begin with longitudinal actigraphy monitoring.

- Protocol: House animals with running wheels and monitor their voluntary activity under constant darkness (DD) conditions before, during, and after drug treatment [29].

- Expected Outcome: In DD, the animal's endogenous circadian period (tau) will manifest. A drug that directly perturbs the core clock mechanism will cause a measurable change in the free-running period (tau) or a reduction in the robustness (amplitude) of the activity rhythm.

Q3: How can we determine the best time of day to administer a drug to minimize toxicity? A: Employ in vitro models that recapitulate human circadian metabolism.

- Protocol: Use engineered human liver models that exhibit robust circadian rhythms in drug-metabolizing enzymes like CYP3A4 [25].

- Procedure: Treat these models with your drug at different circadian time points (simulated by the in vitro cycle) and measure the production of toxic metabolites or markers of cellular stress (e.g., NAPQI for acetaminophen) [25]. This approach can identify a toxicity window and a safer administration window.

Q4: How do we distinguish a drug's direct effect on the clockwork versus its indirect effect through altering behavior (e.g., sleep)? A: This requires a carefully designed experimental separation.

- For direct effects: Use in vitro systems (synchronized cells). Any change in the rhythmicity of clock gene expression is a direct effect on the cellular molecular clock [25].

- For indirect effects: In in vivo studies, control for behavioral confounders. For example, if a drug causes sedation, it might disrupt sleep, which in turn can shift the circadian clock. Using pair-fed controls or controlling for activity levels can help isolate the drug's direct effect.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Circadian Disruption Research

| Item / Reagent | Critical Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Salivary Melatonin Assay Kits | Quantifying melatonin concentration in saliva samples for DLMO phase assessment [27]. | Determining the circadian phase of human subjects before and after a drug intervention. |

| Actigraph Devices | Objective, long-term monitoring of rest-activity and sleep-wake cycles in vivo [28]. | Diagnosing Non-24 Sleep-Wake Disorder or monitoring the stability of circadian behavior in animal models and humans. |

| Circadian Reporter Cell Lines | Real-time, non-invasive monitoring of molecular clock activity in live cells (e.g., Bmal1-luciferase). | Screening for drugs that directly alter the period, phase, or amplitude of the core circadian oscillator in vitro. |

| Engineered Human Liver Models | Studying human-specific circadian metabolism and time-dependent drug toxicity in vitro [25]. | Identifying the time of day when metabolism of a drug candidate produces the highest level of toxic metabolites. |

| qPCR Assays for Clock Genes | Profiling the expression levels of core clock genes (e.g., Bmal1, Per1/2, Cry1/2, Rev-erbα). | Validating that a drug treatment alters the molecular clockwork in tissues or cells. |

| Dexamethasone | A synthetic corticosteroid used to synchronize the circadian clocks in cell cultures for in vitro studies. | Creating a synchronized population of cells to study the direct, cell-autonomous effects of a drug on the molecular clock. |

Key Signaling Pathways & Workflow Diagram

The following diagram integrates the core circadian pathway with the experimental workflows for assessing drug-induced disruption, highlighting the logical relationship between molecular mechanisms, investigative methods, and observed outcomes.

Light-Dark Cycles, Feeding Patterns, and Sleep as Confounding Variables in Hormone Sampling

FAQ: Understanding Confounding Variables

What are confounding variables in the context of circadian hormone research?

A confounding variable is a factor other than the one being studied that is associated with both the exposure (e.g., an experimental medication) and the outcome (e.g., hormone levels) [30]. In circadian hormone sampling, if a factor like sleep timing influences both the drug's metabolism and the natural hormone rhythm, it can distort or mask the true relationship between the medication and the hormonal outcome [31] [30].

Why are light-dark cycles considered a major confounder in hormone studies?

The body's master clock, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), uses light-dark cues to synchronize circadian rhythms [32]. Light exposure directly regulates the secretion of hormones like melatonin [32] [33]. Artificial Light at Night (ALAN) can suppress nocturnal melatonin synthesis, disrupting circadian homeostasis and introducing significant variability in hormone measurements if not controlled [32]. This is a critical consideration when assessing a drug's potential impact on melatonin-related pathways.

How can feeding patterns confound hormone sampling?

Meal timing is a powerful "zeitgeber" (time cue) for peripheral clocks in metabolic tissues like the liver [34]. Consuming meals during the circadian night (when melatonin is high) has been correlated with impaired glucose tolerance [34]. In research, if a medication alters appetite or feeding behavior, or if feeding schedules are inconsistent across study subjects, it becomes nearly impossible to disentangle the drug's direct effects from the metabolic consequences of mistimed feeding on hormones like insulin, ghrelin, and leptin [34] [33].

What is the specific risk of uncontrolled sleep patterns?

Sleep directly regulates the secretion of numerous hormones. For example, growth hormone (GH) release is strongly linked to slow-wave sleep (SWS), and cortisol follows a circadian pattern that is influenced by sleep-wake cycles [33] [35]. Sleep deprivation or disruption activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated cortisol levels [35]. Uncontrolled sleep patterns can therefore be a potent confounder, making it appear that a medication is affecting cortisol or GH levels when the effect is actually due to poor sleep hygiene among participants.

What is "time-varying confounding" and when does it occur?

A time-varying confounder is a factor that changes over the course of a study and continues to influence both the likelihood of an outcome and the exposure status at different time points [36]. In a longitudinal study where participants may start or stop a medication, a variable like stress level is a classic example. Stress can influence the decision to take a medication, is affected by prior medication use, and is independently a risk factor for the outcome (e.g., a specific hormone level). Standard statistical adjustment fails in this scenario because the confounder is also a mediator on the causal pathway [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Hormone Measurements Across Study Cohorts

Potential Cause: Uncontrolled light exposure among participants, leading to misaligned central circadian clocks and hormone rhythms [32].

Solutions:

- Protocol Design: Implement a strict "constant routine" protocol in a lab setting to control for light, posture, and feeding [32]. For field studies, provide participants with actigraphs with light sensors to monitor compliance.

- Participant Guidance: Issue standardized instructions mandating avoidance of bright light, especially blue-wavelength light, for 2-3 hours before target bedtime and during nocturnal samplings.

- Statistical Control: Measure and record the timing of light exposure for use as a covariate in statistical models.

Problem: High Variability in Metabolic Hormone Readouts (e.g., Insulin, Glucose)

Potential Cause: Unstandardized feeding patterns and meal timing relative to participants' sleep-wake cycles [34].

Solutions:

- Standardize Meals: Provide all participants with identical, pre-packaged meals for a defined period (e.g., 24-72 hours) prior to sampling.

- Implement Time-Restricted Feeding (TRF): Confine all caloric intake to a specific and biologically appropriate window, such as an 8-10 hour period during the daytime. Early time-restricted eating has been shown to improve glucose levels and substrate oxidation [34].

- Document Thoroughly: Meticulously record the clock time, macronutrient composition, and size of every meal consumed before and during the sampling period.

Problem: Hormone Levels Do Not Follow Expected Circadian Patterns

Potential Cause: Poorly controlled or documented sleep-wake schedules, leading to circadian disruption or misalignment [33] [35].

Solutions:

- Verify Sleep: Use polysomnography (PSG) or actigraphy to objectively verify sleep timing, duration, and architecture (e.g., SWS, REM) during the study period, rather than relying on self-report [33].

- Stabilize Schedules: Require participants to maintain a fixed sleep-wake schedule (e.g., +/- 30 minutes) for at least one week prior to sampling, verified by actigraphy and sleep diaries.

- Account for Chronotype: Assess participants' innate chronotype (morningness/eveningness) using standardized questionnaires and consider it as a stratifying variable in the analysis [37] [38].

Problem: Suspected Confounding by an Unmeasured Variable

Potential Cause: A factor that influences both the independent and dependent variable was not identified or recorded, making statistical control impossible [31] [30].

Solutions:

- Design Phase: Use restriction by enrolling a homogenous population (e.g., narrow age range, same sex) to eliminate confounding by those factors [31]. For drug studies, use an active comparator design instead of a placebo/no-treatment group to mitigate confounding by indication [31].

- Analysis Phase: Employ propensity score methods (matching or weighting) to create a balanced pseudo-population where treated and untreated subjects have similar distributions of measured confounders [31]. For complex time-varying confounding, advanced methods like G-methods (e.g., inverse probability of treatment weighting) may be necessary [31] [36].

Experimental Protocols for Controlling Confounders

Protocol 1: Controlled Laboratory Sampling for Circadian Hormone Profiles

This protocol is designed to isolate endogenous circadian rhythms from masking effects.

1. Pre-Study Stabilization (7-10 Days at Home): * Participants maintain a fixed 8-hour sleep schedule aligned with their habitual timing. * Adherence is monitored via wrist actigraphy and call-in time stamps. * Meals are standardized and consumed at the same clock times each day.

2. Laboratory Admission (≥ 24 Hours Before Sampling): * Participants enter a laboratory environment free from time cues ("temporal isolation"). * The light-dark cycle is controlled and set to the participant's habitual schedule.

3. Constant Routine Protocol (Initiated for ≥ 18 Hours): * Participants remain in a semi-recumbent posture. * Wakefulness is maintained under dim light conditions (< 10 lux). * Nutritional intake is distributed evenly across the protocol in the form of small, isocaloric snacks every hour. * This protocol unmasking the endogenous circadian rhythm by holding constant the behavioral and environmental factors that normally mask it [32].

4. Hormone Sampling: * Blood samples are drawn frequently (e.g., every 60 minutes) via an indwelling catheter. * Key hormones to assay: Melatonin, Cortisol, GH, TSH, Leptin, Ghrelin [33].

Protocol 2: Standardized Field-Based Sampling for Medication Studies

This protocol maximizes ecological validity while imposing key controls to minimize confounding.

1. Participant Selection and Stratification: * Recruit participants based on similar chronotypes (e.g., intermediate types only) [38]. * Stratify randomization by age, sex, and BMI.

2. Pre-Sampling Control Period (5-7 Days): * Sleep: Fixed sleep-wake schedule (± 1 hour), verified by actigraphy. * Light: Instructions to avoid bright light after sunset and use blue-light blocking glasses if using electronic devices. * Feeding: Consume all calories within a consistent 10-12 hour daytime window (e.g., 08:00 a.m. to 07:00 p.m.). The final meal before sampling should be standardized.

3. Sampling Day: * Time Stamping: Record the exact clock time of every sample. * Context Recording: Document recent activity, posture, and food intake prior to each sample. * Wake-Time Sampling: For morning cortisol, sample immediately upon waking (while still in bed) and again at 30-minute intervals.

Data Presentation: Circadian Hormone Reference Ranges

Table 1: Peak Secretion Timing of Key Hormones Under Controlled Conditions This table summarizes the typical circadian phase of hormone peaks, which serves as a baseline for detecting deviations caused by experimental manipulations or confounders. [33]

| Hormone | Typical Peak Time (Circadian Phase) | Primary Regulator (Circadian/Sleep) | Key Confounding Variables to Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin | 02:00 - 04:00 a.m. (Biological night) | Circadian (Darkness) | Light exposure, posture |

| Cortisol | ~30 mins after wake-time (Biological morning) | Circadian (ACTH surge) | Sleep timing, stress, wake time |

| Growth Hormone (GH) | Early part of nocturnal sleep | Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS) | Sleep depth/architecture, age |

| Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) | Middle of the biological night | Circadian | Sleep deprivation, SWS |

| Testosterone (TT) | Early morning hours | REM Sleep | Sleep structure, age |

| Leptin | Biological night | Circadian/Sleep | Meal timing, energy balance |

| Prolactin (PRL) | During sleep | Sleep-Wake Cycle | Sleep duration |

Table 2: Common Confounding Variables and Methodological Controls

| Confounding Variable | Impact on Hormone Sampling | Recommended Control Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Light at Night | Suppresses melatonin; disrupts central clock timing [32]. | Dim light conditions before/during sampling; actigraphs with light sensors. |

| Irregular Meal Timing | Desynchronizes peripheral clocks; alters glucose, insulin, ghrelin [34]. | Time-restricted feeding; standardized meal composition. |

| Sleep Deprivation / Disruption | Elevates cortisol; blunts GH amplitude; alters TSH [33] [35]. | Actigraphy/PSG; fixed sleep schedules; controlled lab environment. |

| Posture & Activity | Affects plasma volume and hormone concentration. | Controlled posture (semi-recumbent) during sampling in lab studies. |

| Chronotype | Causes phase shifts in rhythms (e.g., earlier in morning types) [38]. | Chronotype assessment; stratification in analysis. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis and Key Confounders

This diagram illustrates the pathway of cortisol regulation and where major confounding variables can interfere, potentially creating the illusion of medication interference.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Controlling Confounders

This flowchart outlines a systematic experimental workflow to identify and control for key confounding variables in circadian hormone sampling research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Confounder-Controlled Circadian Research

| Item | Function & Importance in Controlling Confounders |

|---|---|

| Actigraphs | Worn like a watch to objectively monitor sleep-wake cycles, rest/activity patterns, and (if equipped with light sensors) ambient light exposure. Critical for verifying participant compliance with stabilization protocols outside the lab [37]. |

| Portable Polysomnography (PSG) | The gold standard for objective measurement of sleep architecture (SWS, REM). Essential for studies where the outcome hormone is tightly linked to a specific sleep stage (e.g., GH and SWS) [33] [35]. |

| Dim-Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO) Kit | A standardized protocol to assess the timing of the central circadian clock. Involves serial saliva or plasma sampling under dim light conditions. Used to establish a baseline circadian phase for each participant [32]. |

| Chronotype Questionnaires (e.g., MEQ) | Self-report tools like the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) to categorize participants' innate circadian phase preferences. Allows for stratification in analysis to avoid confounding by phase differences [37] [38]. |

| Controlled Light Environments/Boxes | Light boxes that can deliver specific light intensities and spectra. Used in lab studies to provide a standardized light stimulus or to create a controlled photoperiod, eliminating confounding from variable environmental light [32]. |

| Standardized Meal Kits | Pre-portioned, nutritionally defined meals and snacks. Eliminates confounding from variations in meal size, composition, and timing, ensuring that feeding is a controlled variable, not a confounder [34]. |

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) / ELISA Kits | Specific kits for assaying hormone levels from blood, saliva, or urine. High-sensitivity and low-cross-reactivity kits are essential for accurately measuring the low concentrations and pulsatile secretion of many circadian hormones [33]. |

Protocol Design and Sampling Strategies for Reliable Circadian Data

Gold-Standard Biomarkers for Circadian Phase Assessment in Clinical Trials

Biomarker Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of established and emerging biomarkers for circadian phase assessment.

Table 1: Gold-Standard and Emerging Biomarkers for Circadian Phase Assessment

| Biomarker | Biological Matrix | Key Measured Analytes | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Sources of Interference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO) [18] [27] | Saliva, Plasma | Melatonin | Considered the gold standard; directly reflects the timing signal from the central pacemaker (SCN) [18]. | Requires strict dim-light conditions and frequent sampling over 5-6 hours; inconvenient for large-scale studies [39] [18]. |

| Core Body Temperature (CBT) [18] | Rectal, Gastrointestinal | Core Body Temperature | Robust rhythm generated by the SCN [18]. | Rhythm is easily masked by activity, sleep-wake cycles, and food intake [18]. |

| Transcriptomic Biomarkers (e.g., BodyTime) [39] | Blood (Monocytes) | Expression of a small gene set (e.g., 12 genes) | Requires only a single blood sample; high accuracy comparable to DLMO [39]. | Performance can be affected by the specific training set and experimental conditions used for development [40]. |

| Blood Clock Correlation Distance (BloodCCD) [41] | Blood (Whole Blood) | Expression correlation of 42 circadian-related genes | Provides a single score for circadian disruption; not dependent on time of sample collection [41]. | Novel method requiring further validation; performance in various disease and medication contexts is under investigation [41]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO) Assessment

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for determining DLMO from saliva, which is critical for defining an individual's circadian phase in research and clinical trials [18] [27].

- Primary Materials: Saliva collection kits (salivettes), freezer (-20°C or lower), portable cooler, pre-paid shipping materials [27].

- Sample Collection:

- Begin collection 6-8 hours before habitual bedtime [27].

- Collect 7 to 9 saliva samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) [18] [27].

- Maintain strict dim-light conditions (<10-30 lux) before and during the entire collection period. Participants should avoid overhead lights and use dim, indirect light if necessary.

- Participants should refrain from eating, drinking (except water), brushing teeth, or smoking for at least 30 minutes before each sample.

- Sample Handling:

- Freeze samples immediately after collection.

- Ship frozen on dry ice to a CLIA-certified laboratory for analysis [27].

- Data Analysis:

- Melatonin concentration is typically determined by immunoassay.

- DLMO is calculated as the time point when melatonin concentration crosses a predefined threshold (often 3-4 pg/mL) or a certain percentage above the baseline mean [18].

Blood-Based Transcriptomic Phase Assessment (BodyTime Assay)

This protocol describes a method for estimating internal circadian time from a single blood draw using a targeted gene expression panel [39].

- Primary Materials: PAXgene Blood RNA tubes, RNA extraction kit (e.g., Qiagen PAXgene Blood RNA Kit), globin RNA depletion kit (e.g., GLOBINclear), NanoString nCounter platform and reagents, multiplexed gene expression codeset for the target genes [39] [41].

- Sample Collection and Processing:

- Gene Expression Profiling:

- Use the NanoString nCounter platform for multiplexed gene expression analysis without the need for reverse transcription or amplification [39].

- Hybridize the extracted RNA to the reporter codeset for the specific biomarker genes (e.g., the 12-gene panel from the BodyTime assay) and the capture probeset overnight.

- Data Analysis and Phase Prediction:

- Count the fluorescent barcodes on the nCounter system.

- Normalize the raw data using internal positive controls and housekeeping genes.

- Input the normalized gene expression data into a pre-trained algorithm (e.g., based on ZeitZeiger) to compute the predicted internal circadian time [39].

Diagram 1: Transcriptomic biomarker workflow from sample to result.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Immunoassay and Multiplex Assay Performance

Problem: High variability or low signal in immunoassays (e.g., melatonin or cytokine detection).

- Cause & Solution: Improper sample handling and preparation.

- Action: Always vortex and centrifuge thawed samples at 10,000 × g for 5-10 minutes to remove debris and lipids. For viscous samples like plasma, repeat centrifugation if needed [42].

- Cause & Solution: Inconsistent pipetting technique.

- Action: Use calibrated pipettes, hold the pipette at a consistent angle, and employ reverse pipetting for more precise fluid additions [42].

- Cause & Solution: Incomplete or inconsistent plate washing.

- Action: Use a magnetic separation block and ensure the plate is firmly attached. For manual washing, decant and blot the plate gently. Use the wash buffer provided in the kit [42].

- Cause & Solution: Low bead counts in multiplex bead-based assays (e.g., Luminex).

- Action: Resuspend beads in Wash Buffer (instead of Sheath Fluid) just before reading to prevent clumping. Ensure the instrument is regularly cleaned and calibrated [42].

Problem: Suspected medication interference with hormone (e.g., melatonin) immunoassay.

- Cause & Solution: Cross-reactivity of the drug or its metabolites with the assay antibody.

- Action: Consult the assay manufacturer's data sheet for known cross-reactivities. If possible, use a more specific method like LC-MS/MS for confirmation. Note the medication and dosing schedule of participants as a potential confounding variable.

Transcriptomic Assay Performance

Problem: Poor performance of a transcriptomic biomarker when applied to a new study cohort.

- Cause & Solution: The biomarker was trained on data from experimental conditions (e.g., baseline sleep) that do not match the new study's conditions (e.g., sleep deprivation, shift work).

- Action: Ensure the biomarker has been validated for the specific population and condition of your study. Performance can be significantly degraded when applied to protocols that mimic real-world scenarios like shift work [40].

- Cause & Solution: Overfitting due to a small training set size during biomarker development.

- Action: Select biomarkers developed with established validation concepts and large, diverse training sets to ensure generalizability [40].

Medication Interference in Circadian Hormone Sampling

Many classes of drugs can directly or indirectly interfere with the accurate measurement of circadian hormones, potentially confounding research results.

Table 2: Common Medication Interferences with Circadian Biomarkers

| Medication Class | Example Drugs | Target Circadian Biomarker | Nature of Interference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-Blockers | Propranolol, Atenolol | Melatonin | Suppresses nocturnal melatonin production by blocking adrenergic receptors in the pineal gland [43]. |

| Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) | Ibuprofen, Aspirin | Melatonin | May suppress melatonin synthesis by inhibiting the enzyme N-acetyltransferase [43]. |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) | Fluoxetine, Sertraline | Melatonin, Cortisol | Can alter melatonin synthesis and secretion rhythms; impacts HPA axis and cortisol dynamics [43] [44]. |

| Benzodiazepines | Lorazepam, Diazepam | Cortisol | Can blunt the cortisol awakening response and suppress HPA axis activity [43]. |

| Exogenous Glucocorticoids | Prednisone, Dexamethasone | Cortisol | Directly suppresses endogenous cortisol production via negative feedback on the HPA axis [43]. |

| Catecholamines | --- | Core Clock Genes | Can directly reset peripheral clocks (e.g., in the liver) through signaling pathways, altering circadian gene expression [43]. |

Diagram 2: Mechanisms of medication interference with circadian biomarkers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is DLMO considered the gold standard when it is so burdensome?

DLMO is considered the gold standard because melatonin secretion is directly controlled by the central circadian pacemaker, the SCN, and is less susceptible to masking by non-circadian factors like sleep or posture compared to other markers like core body temperature [18]. It provides a direct readout of the central clock's phase.

Q2: Can I use a transcriptomic biomarker to assess circadian phase in shift workers or individuals with irregular sleep schedules?

Caution is advised. The performance of blood-based biomarkers depends heavily on the conditions of the training data. Biomarkers developed under baseline conditions may not translate accurately to protocols involving sleep restriction or desynchronization, such as shift work [40]. Always check the validation scope of the specific biomarker.

Q3: What is the most critical step in the DLMO protocol to ensure accurate results?

Maintaining strict dim-light conditions is paramount. Even brief exposure to ordinary room light can suppress melatonin secretion and dramatically shift or obscure the DLMO, leading to incorrect phase assessment [27].

Q4: How can I control for the effects of medications in my circadian research?

- Documentation: Meticulously record all medications, including dosage and timing, for all participants.

- Exclusion Criteria: Consider excluding participants on medications known to strongly interfere with your primary circadian biomarkers (see Table 2).

- Statistical Control: For medications that cannot be excluded, plan to include them as covariates in your statistical models.

- Pilot Testing: If a participant is on a critical medication, consider running a pilot assay to check for obvious interference.

Q5: Are there emerging biomarkers that could replace DLMO in the future?

Yes, methods like the BodyTime assay (transcriptomic) [39] and BloodCCD (correlation-based) [41] show great promise. Their key advantage is requiring only one or a few samples, greatly reducing participant burden. However, they are still being validated across diverse populations and conditions and are not yet considered a universal replacement for DLMO [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Circadian Phase Assessment Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Salivettes | Hygienic collection and stabilization of saliva samples for hormone (melatonin, cortisol) analysis [27]. | Sarstedt Salivette |

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Collect and stabilize intracellular RNA from whole blood for transcriptomic biomarker analysis [39] [41]. | BD PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Purify high-quality total RNA from stabilized blood samples. | Qiagen PAXgene Blood RNA Kit [41] |

| Globin RNA Depletion Kit | Improve detection of non-globin transcripts in whole blood RNA-seq by removing highly abundant globin mRNAs [41]. | Thermo Scientific GLOBINclear Kit |

| NanoString nCounter Platform | Multiplexed digital quantification of gene expression without amplification, used in validated transcriptomic assays [39]. | NanoString nCounter SPRINT/FLEX |

| Luminex xMAP Technology | Multiplexed quantification of soluble analytes (e.g., cytokines) using magnetic beads and fluorescent detection [42]. | MILLIPLEX MAP Assays |

| Handheld Magnetic Separator | Efficiently separate magnetic beads from solution during wash steps in immunoassays [42]. | EMD Millipore Magnetic Separator Block |

| Chloronaphthol (4-CN) | Substrate for horseradish peroxidase (HRP) used in enzymatic signal enhancement assays on some biosensor platforms [45]. | 4-Chloro-1-naphthol |

Optimal Sampling Frequencies and Timing for Capturing Endocrine Rhythms

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Inconsistent Circadian Phase Estimates

Problem: Measurements from different biomarkers (e.g., melatonin vs. cortisol) provide conflicting estimates of a subject's circadian phase.

Explanation: Different circadian outputs can be influenced by varying masking factors. For instance, cortisol is strongly affected by stress and posture, while melatonin is more robust but requires strict dim light conditions [46] [2]. The peripheral clocks in different tissues may also show slight phase variations [47] [2].

Solution:

- Prioritize Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO): When possible, use DLMO as the primary phase marker, as it is considered the gold standard and is less susceptible to non-photic masking [46].

- Control conditions strictly: For all biomarkers, implement strict protocols regarding posture, light exposure, and meal timing during sampling [46].

- Use a constant routine protocol: If feasible and ethically permissible, use a constant routine protocol to unmask the endogenous circadian rhythm by keeping participants in a constant environment of wakefulness, posture, and caloric intake [46].

- Cross-validate with a second marker: In clinical settings, if DLMO is not possible, use a combination of markers (e.g., wrist temperature and cortisol) and compare the results to identify potential masking effects [48] [2].

Guide 2: Addressing High Participant Burden in Dense Sampling

Problem: Frequent sampling over a 24-48 hour period leads to poor participant compliance and increased dropout rates.

Explanation: Capturing the full profile of a circadian rhythm traditionally requires sampling every 1-2 hours for at least 24 hours, which is burdensome [2]. This is often necessary for robust curve fitting and accurate determination of rhythm parameters like acrophase (peak time) and amplitude.

Solution:

- Optimize sampling strategy: Recent research suggests that with advanced computational methods, fewer time points may be sufficient. One study indicates that as few as 3-4 strategic time points per day over 2 days can be used to assess circadian gene expression in saliva [2].

- Choose less invasive methods: Utilize non-invasive sampling materials like saliva, which participants can collect themselves at home, rather than repeated blood draws [2].

- Implement careful timing: Schedule sampling times to capture key phases of the rhythm, such as the anticipated rise, peak, and decline of the hormone of interest, rather than equidistant intervals [46].

Guide 3: Mitigating Medication Interference on Circadian Biomarkers

Problem: The very medications being studied are suspected of altering the circadian rhythms you are trying to measure.

Explanation: Many medications, including antipsychotics and antidepressants, can directly or indirectly affect the circadian system. They may alter the expression of core clock genes (e.g., CLOCK, BMAL1, PER), shift sleep-wake cycles, or modify the levels of circadian hormones like melatonin and cortisol [24]. This creates a confounding loop in research.

Solution:

- Establish a baseline: If ethically possible, measure circadian parameters (e.g., DLMO, actigraphy) in a medication-free baseline period before administering the drug [24] [46].

- Monitor clock gene expression: In addition to hormones, track the expression of core clock genes in accessible tissues like saliva or blood cells. This can provide a more direct measure of the medication's impact on the molecular clock [24] [2].

- Use a control group: Include a matched control group that does not receive the medication but undergoes identical sampling and monitoring procedures.

- Longitudinal sampling: Design studies with multiple sampling time points over weeks to track the evolution of circadian changes in response to medication, rather than relying on a single snapshot [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the minimum number of sampling time points needed to reliably estimate a circadian rhythm?