Beyond the Calendar: Addressing Methodological Challenges in Menstrual Cycle Endpoint Measurement for Robust Clinical Research

This article synthesizes current evidence and consensus recommendations to address the critical methodological challenges in measuring menstrual cycle endpoints for clinical and research applications.

Beyond the Calendar: Addressing Methodological Challenges in Menstrual Cycle Endpoint Measurement for Robust Clinical Research

Abstract

This article synthesizes current evidence and consensus recommendations to address the critical methodological challenges in measuring menstrual cycle endpoints for clinical and research applications. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational need for standardized measurement, critiques common methodological pitfalls like phase estimation, and presents rigorous verification tools from hormonal assays to wearable technology. It further provides a troubleshooting guide for optimizing study design and a comparative analysis of validation frameworks. The goal is to advance the quality and reliability of female-specific health research by promoting methodological rigor and transdisciplinary standardization in menstrual cycle science.

The Imperative for Precision: Why Standardized Menstrual Cycle Measurement is a Research Priority

FAQs: Methodological Challenges in Menstrual Cycle Research

FAQ 1: Why is it methodologically unsound to assume menstrual cycle phases based on calendar counting alone?

Assuming cycle phases based solely on the calendar day is considered "guessing" and lacks validity and reliability [1]. This approach fails to account for the high prevalence (up to 66% in exercising females) of subtle menstrual disturbances, such as anovulatory or luteal phase deficient cycles, which present with meaningfully different hormonal profiles despite normal cycle length [1]. Relying on a calendar-based method without hormonal confirmation risks linking research data to an incorrect hormonal milieu, leading to invalid conclusions about cycle-phase-dependent effects on health, training, or performance [1].

FAQ 2: What is the critical distinction between a 'eumenorrheic' cycle and a 'naturally menstruating' individual in research?

Terminology is critical [1]. A eumenorrheic cycle is confirmed through advanced testing (e.g., evidence of a luteinizing hormone surge and a sufficient progesterone profile in the luteal phase) and represents an ovulatory cycle with a characteristic hormonal profile [1]. In contrast, the term naturally menstruating should be applied when cycle regularity (21-35 days) is established through calendar-based counting, but no advanced testing confirms the hormonal profile [1]. In this case, the cycle can only be reliably split into menstruation and non-menstruation days, not into specific hormonal phases [1].

FAQ 3: What is the gold standard design for studying within-person effects of the menstrual cycle?

The menstrual cycle is fundamentally a within-person process [2] [3]. Therefore, repeated measures studies are the gold standard [2]. Treating the cycle or its phases as a between-subject variable conflates within-person variance with between-subject variance and lacks validity [2] [3]. For reliable estimation, a minimum of three observations per person across one cycle is suggested, though three or more observations across two cycles provides greater confidence in the reliability of between-person differences in within-person changes [2].

FAQ 4: How can researchers accurately identify the periovulatory and luteal phases for lab testing?

Scheduling lab visits for specific phases requires forward planning based on physiological markers, not just the calendar [2] [3].

- Predicting Ovulation: Use at-home urinary luteinizing hormone (LH) test kits. A positive test indicates the LH surge, with ovulation typically occurring 24-36 hours later [2] [3].

- Confirming the Luteal Phase: The luteal phase can be confirmed after ovulation via a rise in progesterone. This can be measured retrospectively from serum samples or quantitatively from urine as pregnanediol glucuronide (PDG) [2] [4]. The rise in basal body temperature (BBT) also provides a retrospective confirmation of ovulation [2] [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent or conflicting findings in cycle phase literature.

- Potential Cause: Use of assumed or estimated menstrual cycle phases without hormonal verification, leading to misclassification of participants' true hormonal status [1].

- Solution: Implement direct measurement of key hormonal endpoints to characterize cycle phases. For example, confirm ovulation via urinary LH surge kits and verify luteal phase viability with serum progesterone or urinary PDG [1] [2] [4]. Transparently report all methods and their limitations.

Problem 2: High variability in outcome measures within the same presumed cycle phase.

- Potential Cause: Failure to account for substantial between-person differences in sensitivity to hormonal changes (e.g., individuals with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)) or naturally occurring variations in follicular phase length [2] [3].

- Solution: Treat the cycle as a within-person variable and use study designs that allow for the assessment of individual differences. Increase the density of sampling (e.g., daily hormone measures) and use statistical models like multilevel modeling that can separate within-person and between-person effects [2] [3].

Problem 3: Participant drop-out due to the burden of intensive monitoring.

- Potential Cause: Traditional serum-based hormone monitoring is invasive and requires clinic visits, which can be burdensome [4].

- Solution: Leverage validated, quantitative at-home urine hormone monitors (e.g., Mira monitor) that track hormones like FSH, E1G, LH, and PDG [4]. These tools facilitate dense, longitudinal data collection in ecologically valid settings while providing research-grade information.

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Phase Verification

Protocol for Confirming Ovulation and Luteal Phase Function

Objective: To prospectively identify the ovulatory phase and retrospectively confirm a viable luteal phase. Materials: Urinary LH test kits, materials for serum collection (venipuncture), or a quantitative urinary hormone monitor capable of measuring PDG [2] [4].

| Step | Procedure | Measurement Endpoint |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Starting on ~cycle day 8-10, instruct participants to perform daily urinary LH tests each morning. | A positive LH test, indicated by a test line as dark as or darker than the control line. |

| 2. | Schedule a lab visit for 5-7 days after a positive LH test. | Collect a serum sample for progesterone analysis. |

| 3. | (Alternative) Use a quantitative urinary hormone monitor for daily tracking from cycle start. | Identify the LH peak and the subsequent sustained rise in PDG levels. |

Validation Criteria: A serum progesterone level of > 16 nmol/L (or ~5 ng/mL) is a common threshold to confirm that ovulation has occurred [1] [2]. For urinary PDG, the specific threshold should be validated against serum or ultrasound, but a sustained rise is indicative of luteal activity [4].

Protocol for Quantifying Hormonal Profiles Across the Cycle

Objective: To characterize the full hormonal trajectory of the menstrual cycle for precise phase classification. Materials: Quantitative at-home urine hormone monitor (e.g., Mira) and corresponding test wands (e.g., Mira Plus wands measuring FSH, E1G, LH, PDG) [4].

| Step | Procedure | Measurement Endpoint |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | From the first day of menstruation (cycle day 1), participants use the monitor to test first-morning urine daily. | The device provides quantitative values for FSH, E1G, LH, and PDG. |

| 2. | Data is synced to a companion app and/or research database. | Hormone profiles are plotted over time. |

| 3. | Phase determination is based on hormone patterns: - Late Follicular: Rising E1G, low PDG. - Ovulatory: LH surge, peak E1G. - Luteal: Sustained rise in PDG, followed by a perimenstrual decline. | The specific day of ovulation can be estimated from the LH peak, and luteal phase function is assessed via PDG levels. |

Gold Standard Validation: This protocol is currently being validated in research against serial transvaginal ultrasound (the gold standard for pinpointing ovulation) and serum hormone levels to establish its accuracy [4].

Flowchart for Phase Verification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials required for rigorous menstrual cycle phase determination in research settings [2] [3] [4].

Table: Essential Materials for Menstrual Cycle Phase Determination Research

| Item | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Urinary LH Test Kits | Predicts ovulation by detecting the luteinizing hormone surge in urine. | Cost-effective and practical for field-based or remote studies. Ideal for scheduling lab visits around the periovulatory phase. |

| Quantitative Urinary Hormone Monitor (e.g., Mira) | Provides quantitative daily values for FSH, E1G, LH, and PDG from urine to map the entire hormonal profile. | Enables dense, longitudinal data collection at home. Validated against serum and ultrasound is ongoing [4]. |

| ELISA Kits for Serum Progesterone | Precisely measures serum progesterone concentration to confirm ovulation and luteal phase function. | Considered a standard; requires a clinic visit for blood draw. A level >16 nmol/L is a common threshold for confirming ovulation [1] [2]. |

| Basal Body Temperature (BBT) Thermometer | Tracks the slight, sustained rise in resting body temperature that occurs after ovulation. | A low-cost method, but only provides retrospective confirmation of ovulation. Subject to confounding by illness, poor sleep, and alcohol [2] [5]. |

| Validated Daily Symptom Logs/Apps | Tracks participant-reported outcomes (mood, pain, bleeding) prospectively to avoid recall bias. | Critical for diagnosing conditions like PMDD. Retrospective recall of symptoms is highly unreliable and not recommended [2] [3]. |

Methodology and Outcome Relationship

In health research, particularly in the methodologically complex field of menstrual cycle science, measurement neglect poses a substantial threat to both scientific validity and public health. The systematic failure to implement rigorous measurement protocols generates cascading effects that compromise data quality, distort research findings, and ultimately erode public trust in scientific institutions. This technical support center document addresses these challenges within the specific context of menstrual cycle endpoint measurement, where biological complexity intersects with pressing clinical and research needs.

The menstrual cycle represents a fundamental indicator of health and physiological function, often described as the "fifth vital sign" for individuals who menstruate [4]. Despite its significance, research in this domain remains fractured across disciplines and hampered by inconsistent methodologies [6]. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with targeted troubleshooting guidance to identify, diagnose, and resolve common measurement challenges in menstrual health research.

The Impact of Measurement Neglect: Evidence and Consequences

Documented Consequences of Poor Data Quality

Inadequate attention to measurement quality and data integrity produces demonstrable harm across multiple dimensions of health research and practice. The following table summarizes key documented impacts:

| Impact Area | Documented Consequence | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Public Health Policy | Misguided interventions based on inaccurate prevalence data | CDC's false COVID-19 cleaning practices report led to unnecessary public health recommendations [7] |

| Clinical Research Validity | Compromised findings from unvetted respondents | Inattentive respondents inflated dangerous behavior reports by nearly 20% in replication studies [7] |

| Menstrual Research Specificity | Limited generalizability and selection bias | Studies focusing only on women trying to conceive or with regular cycles miss critical population variability [8] |

| Measurement Precision | Inability to detect true physiological signals | Subjective "light" vs. "heavy" bleeding classifications show poor correlation with quantitative measures [8] |

| Trust in Institutions | Erosion of public confidence in scientific bodies | Media amplification of flawed data damages institutional credibility [7] |

Methodological Challenges in Menstrual Cycle Research

Menstrual cycle research faces particular methodological vulnerabilities that amplify the consequences of measurement neglect:

- Selection Bias: Studies frequently overrepresent White populations, women with regular cycles, and those attempting conception, limiting generalizability [8].

- Informative Cluster Size: In fertility studies, women with less fertile cycles contribute more data, potentially skewing characterizations of "normal" cycle patterns [8].

- Definitional Inconsistency: Variations in defining menses onset, bleeding intensity, and cycle parameters hinder cross-study comparisons [8] [6].

- Endpoint Measurement: Subjective assessments of bleeding intensity lack precision, with 40% of women with heavy menstruation considering it normal [8].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Measurement Challenges

Guide 1: Addressing Data Quality and Respondent Vetting Issues

Problem: Suspect data quality from inattentive or fraudulent survey respondents.

Symptoms:

- Unexpectedly high prevalence rates for rare behaviors

- Inconsistent response patterns within subjects

- Aberrant data distributions contradicting established literature

Diagnostic Steps:

- Implement attention checks: Incorporate instructional attention checks (e.g., "Select 'sometimes' for this item") and patterned responses to identify inattentive respondents [7].

- Analyze response distributions: Examine data for statistically improbable responses that may indicate fraudulent or inattentive participants.

- Compare with established benchmarks: Check findings against previously validated population estimates to identify significant deviations.

Resolution Protocols:

- Pre-study vetting: Implement behavioral and technical screening tools like Sentry to prevent problematic respondents from entering studies [7].

- Multi-measure validation: Combine attention checks with open-ended responses and analysis of response tendencies to identify quality issues [7].

- Provider accountability: Require sample providers to supply evidence of their screening methodologies and effectiveness data [7].

Guide 2: Resolving Menstrual Cycle Endpoint Measurement Errors

Problem: Inaccurate characterization of menstrual cycle parameters (bleeding, blood, pain, perceptions).

Symptoms:

- High within-woman variability in cycle phase length reporting

- Discrepancies between subjective bleeding assessments and quantitative measures

- Inability to compare findings across studies due to definitional differences

Diagnostic Steps:

- Audit measurement instruments: Review whether data collection tools have been validated against gold standards like quantitative blood loss measurement or urinary hormone monitoring [6] [4].

- Assess temporal precision: Evaluate how precisely cycle start dates and symptom onset are recorded, as participant recall introduces significant error [8].

- Check for objective correlates: Determine whether subjective measures are supplemented with objective indicators (e.g., product saturation, hormone levels) [8].

Resolution Protocols:

- Adopt standardized frameworks: Implement FIGO criteria for normal uterine bleeding parameters (frequency: 24-38 days; duration: ≤8 days; regularity: ±4 days) [6].

- Implement quantitative tools: Utilize validated instruments like the Mansfield-Voda-Jorgensen Menstrual Bleeding Scale for bleeding assessment [4].

- Incorporate hormonal verification: Where feasible, employ quantitative urine hormone monitors (e.g., Mira monitor measuring FSH, E13G, LH, PDG) to confirm ovulation and cycle phase [4].

Guide 3: Correcting Selection Bias and Generalizability Limitations

Problem: Research findings that cannot be generalized beyond the immediate study population.

Symptoms:

- Homogeneous participant demographics not representing target population

- Exclusion of participants with irregular cycles or specific health conditions

- Volunteer bias from participants with particular interest in menstrual cycle tracking

Diagnostic Steps:

- Analyze participant demographics: Compare study population characteristics with broader target population metrics.

- Review exclusion criteria: Assess whether exclusion criteria unnecessarily restrict participant diversity (e.g., limiting to "regular cycles" when studying cycle variability).

- Evaluate recruitment methods: Determine whether recruitment strategies systematically exclude certain subgroups.

Resolution Protocols:

- Purposive sampling: Implement strategies to ensure ethnically diverse samples reflective of target populations [4].

- Broad inclusion criteria: Where scientifically justified, include participants with irregular cycles, diverse ages, and varying pregnancy intentions [8].

- App-based data collection: Consider menstrual tracking apps to expand beyond typical volunteer populations, while acknowledging their limitations [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What defines an adequate sample size for menstrual cycle research? A: Avoid rules of thumb; calculate sample size based on specific parameters of interest. One ultrasound validation study targeted 50 participants over 3 cycles (150 total cycles) to detect differences of 0.5 days in ovulation timing with 80% power [4]. Always conduct power analyses specific to your research questions and account for anticipated dropout rates.

Q2: How can we accurately capture subjective menstrual experiences like pain and bleeding intensity? A: Use validated instruments that combine subjective reports with objective correlates. For bleeding intensity, implement pictorial blood loss assessment charts alongside qualitative descriptions. For pain, utilize standardized scales with clear anchors. Always document the specific instruments used to enable cross-study comparisons [6].

Q3: What are the ethical considerations in menstrual cycle app data collection? A: Key considerations include data privacy and security (several major apps have experienced data breaches), transparent informed consent regarding data usage, and appropriate representation of diverse populations in algorithm development. Ensure compliance with relevant regulations and consider implementing data anonymization protocols [4].

Q4: How does the "mere-measurement effect" impact menstrual cycle research? A: The mere-measurement effect describes how the act of measurement itself can influence participants' perceptions and behaviors. In menstrual research, repeatedly asking about symptoms may heighten awareness or change tracking behaviors. Mitigate this by considering control groups without intensive measurement and documenting potential measurement effects in limitations [9].

Q5: What strategies exist for handling missing menstrual cycle data? A: Methods like multiple imputation make strong assumptions but are often preferable to complete-case analysis, which makes even stronger assumptions. Choose handling methods based on the missing data mechanism (MCAR, MAR, MNAR) and conduct sensitivity analyses to assess robustness of findings to different approaches [10].

Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

The following table outlines key methodological approaches and their applications for robust menstrual cycle research:

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary Hormone Monitors | Mira monitor (FSH, E13G, LH, PDG) [4] | At-home ovulation prediction and confirmation | Correlate with serum values and ultrasound for validation |

| Bleeding Assessment Tools | Mansfield-Voda-Jorgensen Menstrual Bleeding Scale [4] | Standardized quantification of blood loss | Validated against direct measurement of fluid loss |

| Cycle Tracking Apps | Customized research applications with privacy protections [4] | Longitudinal data collection on multiple parameters | Ensure data security and validate against gold standards |

| Ultrasound Verification | Serial follicular tracking via endovaginal ultrasound [4] | Gold standard for ovulation confirmation | Resource-intensive but provides definitive phase identification |

| Serum Hormone Correlates | Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) for ovarian reserve [4] | Contextualizing cycle characteristics | Single values less valuable than dynamic patterns |

Visualizing the Trust Erosion Pathway in Data Quality Failures

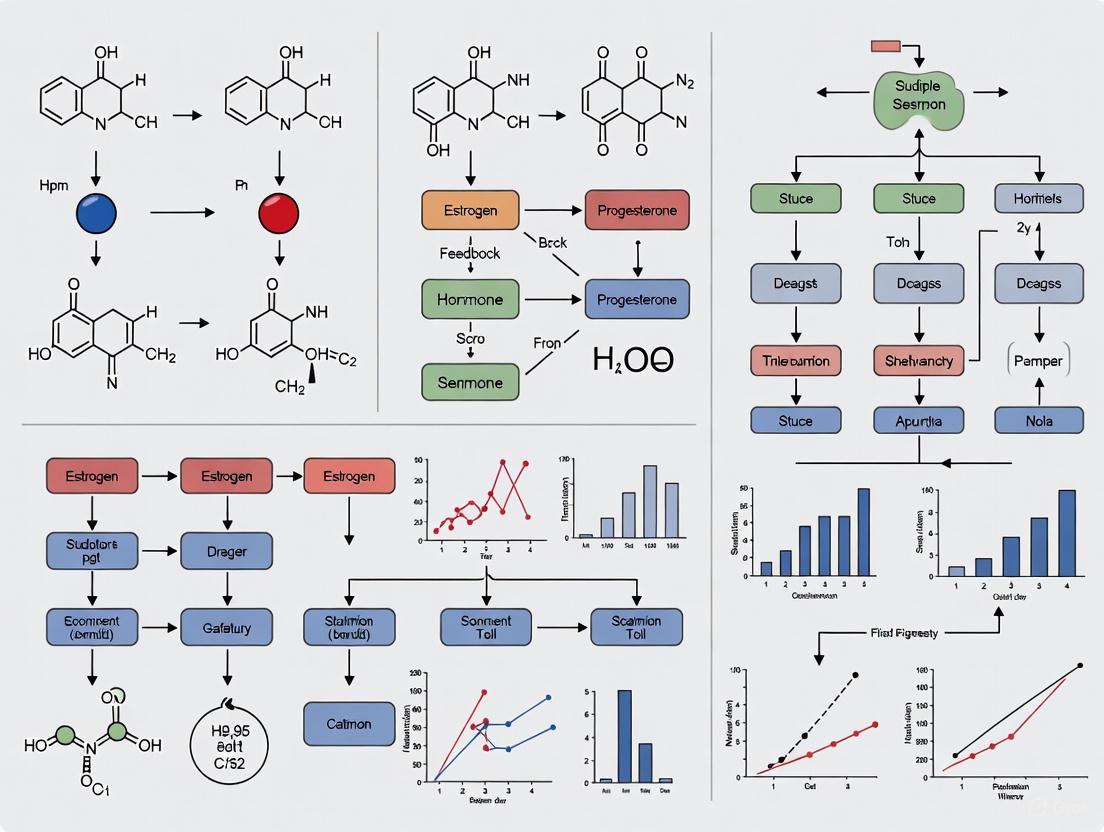

The following diagram illustrates how measurement neglect triggers a cascade of effects culminating in institutional trust erosion:

Visualizing the Menstrual Cycle Research Validation Pathway

This workflow depicts the integration of multiple validation methods for robust menstrual cycle measurement:

Addressing measurement neglect in menstrual cycle research requires concerted implementation of validated methodologies, vigilant data quality practices, and inclusive study designs. By adopting the troubleshooting approaches outlined in this technical support document, researchers can enhance the validity and impact of their work while contributing to the restoration of scientific trust. The development of transdisciplinary standards for menstrual cycle assessment represents a critical frontier in reproductive health research—one that demands methodological rigor equal to the biological complexity and societal importance of this fundamental physiological process.

The study of the menstrual cycle is inherently transdisciplinary, spanning fields from gynecology and sports physiology to psychology and public health. Despite its profound importance as a key indicator of health and wellbeing, research remains fractured across numerous disciplines, each with its own methodologies and terminologies. A recent systematic review highlighted this issue, finding that of 94 identified instruments for measuring menstrual changes, only three had good scores for both quality and utility for clinical trials [6]. This lack of standardization creates significant challenges for comparing results across studies, conducting systematic reviews, and accumulating knowledge about menstrual cycle function [2] [3]. The consequences extend beyond academic circles—during the introduction of COVID-19 vaccinations, the absence of systematic data collection on menstrual changes in vaccine trials led to confusion and eroded trust when people experienced cycle alterations [6]. This technical support center aims to bridge this disciplinary divide by providing standardized troubleshooting guides, methodologies, and frameworks for researchers across all fields studying menstrual endpoints.

Foundational Concepts: Understanding Menstrual Cycle Parameters

Defining Core Menstrual Cycle Characteristics

A eumenorrheic (healthy) menstrual cycle is characterized by predictable fluctuations in ovarian hormones, primarily estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4), which drive both reproductive and systemic effects throughout the body [2]. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) establishes four key parameters for normal uterine bleeding: frequency (every 24-38 days), duration (up to 8 days), regularity (cycle length variation of ± 4 days), and volume (defined as "normal" by the patient without quality of life interference) [6]. The average menstrual cycle lasts 28 days, but healthy cycles can vary between 21-37 days [2]. The follicular phase (day 1 until ovulation) typically lasts 15.7 days but shows considerable variability, while the luteal phase (post-ovulation until menstruation) is more consistent at approximately 13.3 days [2].

Hormonal Dynamics Across Cycle Phases

The menstrual cycle features complex hormonal interactions that can be divided into six distinct phases based on hormonal fluctuations: early follicular, late follicular, ovulation, early luteal, mid-luteal, and late luteal [11]. Estradiol rises gradually through the mid-follicular phase, spikes dramatically before ovulation, and exhibits a secondary peak during the mid-luteal phase. Progesterone remains low during the follicular phase but rises gradually after ovulation, peaking during the mid-luteal phase before declining rapidly if no fertilization occurs [2]. These hormonal fluctuations have systemic effects beyond reproduction, influencing metabolism, immune function, neural processing, and cardiovascular regulation [11] [2].

Table 1: Key Hormonal Fluctuations Across the Menstrual Cycle Phases

| Cycle Phase | Estradiol (E2) | Progesterone (P4) | Other Key Hormones |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Follicular | Low and stable | Low and stable | FSH begins to rise |

| Late Follicular | Rapid rise and peak | Low and stable | LH surge triggers ovulation |

| Ovulation | Sharp decline post-surge | Begins to rise | LH and FSH peak |

| Early Luteal | Secondary rise | Gradual increase | - |

| Mid-Luteal | Secondary peak | Peaks | - |

| Late Luteal | Decline | Sharp decline | - |

Common Methodological Challenges & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Determining Menstrual Cycle Phase

Q: What is the most accurate method for determining menstrual cycle phase in research settings?

A: The most rigorous approach involves a combination of methods rather than relying on a single indicator. The gold standard includes: (1) Forward-count and backward-count methods for cycle day calculation using menstrual start dates as anchor points; (2) Urinary luteinizing hormone (LH) testing to identify the pre-ovulatory surge; (3) Serum or salivary hormone measurement of estradiol and progesterone; and (4) Basal body temperature (BBT) tracking to confirm ovulation through the biphasic pattern [2] [3]. Quantitative urine hormone monitors that measure multiple hormones (FSH, E1G, LH, PDG) show promise for at-home monitoring while maintaining accuracy comparable to serum measurements [4].

Q: Why can't I rely solely on calendar counting or period-tracking apps for phase determination?

A: Calendar counting alone is insufficient because menstrual cycle length variability is primarily attributable to follicular phase variation [2]. Additionally, a significant percentage of cycles that appear regular by calendar tracking actually exhibit subtle menstrual disturbances such as anovulation or luteal phase deficiency [12]. One study found that when cycles are assessed solely based on regular menstruation, up to 66% of exercising females had undetected menstrual disturbances despite normal cycle lengths [12]. Most menstrual tracking apps have been shown to be inaccurate, with additional concerns about data privacy and security [4].

FAQ: Participant Selection and Characterization

Q: What criteria should I use to characterize participants as "eumenorrheic" in my study?

A: A eumenorrheic menstrual cycle should be characterized by: (1) cycle lengths ≥21 days and ≤35 days; (2) nine or more consecutive periods per year; (3) evidence of an LH surge; and (4) the correct hormonal profile with confirmed ovulation and sufficient progesterone during the luteal phase [12]. The term "naturally menstruating" should be used when cycle length criteria are met but no advanced testing confirms the hormonal profile. Transparent reporting of which criteria were used for participant characterization is essential for study interpretation and replication [12].

Q: How can I account for between-person differences in hormone sensitivity?

A: Between-person differences in hormone sensitivity are substantial and clinically meaningful. Approximately 3-8% of reproductive-aged people meet diagnostic criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD), indicating abnormal sensitivity to normal hormone changes [2]. Research demonstrates that beliefs about premenstrual symptoms can influence retrospective reports, so prospective daily monitoring for at least two consecutive cycles is required for accurate PMDD diagnosis [2]. The Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS) provides a standardized system for diagnosing PMDD and premenstrual exacerbation of underlying disorders based on daily symptom ratings [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Methodological Errors

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Methodological Challenges in Menstrual Cycle Research

| Problem | Potential Consequences | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Assuming/estimating cycle phases without hormonal verification | Misattribution of phase; inclusion of anovulatory cycles; inaccurate conclusions about hormone-outcome relationships | Implement multi-method verification (LH testing, BBT, hormonal assays); clearly report verification methods and limitations [12] |

| Between-subjects designs treating cycle as between-person variable | Conflating within-person and between-person variance; inability to detect true cycle effects | Use repeated measures designs with at least 3 observations per participant across the cycle; employ multilevel modeling [2] |

| Inconsistent endpoint measurement across studies | Inability to compare findings; limited utility for systematic reviews and meta-analyses | Adopt FIGO standards for bleeding parameters; use validated instruments with good quality and utility scores [6] |

| Failure to account for contraceptive use | Confounding of natural cycle patterns; inappropriate grouping of participants | Screen for and document all hormonal contraceptive use; consider contraceptive users as a separate group [8] |

| Retrospective symptom reporting | Recall bias; false positive reports of premenstrual symptoms | Implement prospective daily monitoring; use validated daily symptom rating tools [2] |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantitative Menstrual Cycle Monitoring With Hormone Verification

Objective: To precisely track menstrual cycle phases using a combination of hormonal verification methods and bleeding patterns.

Materials:

- Urinary luteinizing hormone (LH) test strips

- Basal body thermometer (digital preferred)

- Menstrual cycle tracking app or diary

- Optional: quantitative urine hormone monitor (e.g., Mira monitor)

- Optional: salivary or serum hormone testing kits

Procedure:

- Participant Training: Train participants in proper LH testing technique, BBT measurement (upon waking, before rising), and bleeding documentation.

- Cycle Day 1 Identification: Instruct participants to mark the first day of menstrual bleeding (full red flow) as Cycle Day 1.

- LH Surge Monitoring: Begin daily LH testing from approximately cycle day 7-10 until surge is detected. Testing should occur at similar times each day, with limited fluid intake beforehand.

- BBT Tracking: Measure and record BBT daily upon waking throughout the entire cycle.

- Bleeding Documentation: Record bleeding patterns daily using standardized categories (spotting, light, medium, heavy).

- Hormonal Verification: For increased precision, schedule laboratory visits during key phases (early follicular, periovulatory, mid-luteal) for serum hormone confirmation or use quantitative urine hormone monitors.

Validation Criteria:

- Ovulation Confirmation: Detected LH surge followed by sustained BBT elevation within 1-3 days that remains elevated for at least 10 days.

- Follicular Phase: From menstruation onset (Cycle Day 1) until day before LH surge.

- Luteal Phase: From day after LH surge until day before next menstruation.

This protocol combines the accessibility of at-home tracking with the precision of hormonal verification, balancing practical concerns with scientific rigor [4] [3].

Protocol: Standardized Menstrual Bleeding Assessment

Objective: To quantitatively and qualitatively assess menstrual bleeding patterns using validated instruments.

Materials:

- Validated pictorial blood loss assessment chart (PBLAC)

- Mansfield-Voda-Jorgensen Menstrual Bleeding Scale (MVJ)

- Daily bleeding diary

- Menstrual products for saturation assessment (if applicable)

Procedure:

- Bleeding Volume Assessment:

- Distribute PBLAC to participants at beginning of study

- Instruct participants to record number of sanitary products used each day and degree of saturation

- Provide standardized pictorial guides for saturation estimation

- Bleeding Pattern Documentation:

- Implement daily bleeding diaries using categorical ratings (none, spotting, light, medium, heavy)

- Use validated scales such as MVJ for consistent categorization

- Cycle Parameter Calculation:

- Calculate cycle length from Day 1 of bleeding to Day 1 of subsequent bleeding

- Document bleeding duration in days

- Assess regularity through cycle length variation across multiple cycles

Analysis:

- Apply FIGO standards for normal uterine bleeding parameters

- Calculate intermenstrual bleeding episodes separately from menstrual bleeding

- Document impact on quality of life and activities of daily living [6] [4]

Visualization: Experimental Workflows and Methodological Relationships

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Menstrual Cycle Research Methodology

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Instruments

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Standardized Menstrual Endpoint Measurement

| Tool Category | Specific Instruments/Assays | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone Verification | Urinary LH test strips | Detection of LH surge predicting ovulation | Test timing critical; false surges possible |

| Quantitative urine hormone monitors (e.g., Mira) | Measures multiple hormones (FSH, E1G, LH, PDG) | Emerging technology; requires validation [4] | |

| Serum hormone assays (E2, P4) | Gold standard hormone quantification | Resource-intensive; limited sampling frequency | |

| Salivary hormone kits | Non-invasive hormone measurement | Validation against serum required [3] | |

| Cycle Tracking | Basal body thermometer | Detection of post-ovulatory temperature shift | Requires consistent morning measurement |

| Menstrual bleeding diaries | Documentation of timing and intensity | Use validated scales (e.g., MVJ) [4] | |

| Pictorial blood loss assessment | Quantitative bleeding measurement | Correlates with actual blood loss [6] | |

| Symptom Assessment | Daily symptom rating scales | Prospective symptom monitoring | Essential for PMDD/PME diagnosis [2] |

| Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS) | Standardized PMDD/PME diagnosis | Available as worksheet, Excel, R, SAS macros [2] | |

| Data Analysis | Multilevel modeling software | Appropriate statistical analysis for repeated measures | Accounts for within-person variability [2] |

Standardizing menstrual endpoint measurement across disciplines requires concerted effort to adopt common methodologies, terminologies, and validation criteria. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and methodological frameworks outlined in this technical support center, researchers across diverse fields can contribute to a more coherent and cumulative science of menstrual health. The transdisciplinary need for standardized menstrual endpoints extends beyond academic consistency—it represents a fundamental requirement for advancing understanding of a key physiological process that influences nearly every aspect of health and wellbeing for half the global population. As research in this area accelerates, particularly in elite sport and pharmaceutical development, maintaining methodological rigor while developing pragmatic approaches for diverse research settings will be essential for generating valid, reliable, and actionable knowledge.

The study of the menstrual cycle is fraught with methodological inconsistencies that have significantly impeded scientific progress and the development of safe, effective treatments for people who menstruate. Despite decades of research, laboratories worldwide have failed to adopt consistent methods for operationalizing the menstrual cycle, leading to substantial confusion in the literature and frustrating attempts at systematic reviews and meta-analyses [2]. This problem is particularly acute in clinical trials, where the recent introduction of COVID-19 vaccinations highlighted critical gaps in data collection when vaccinated individuals reported menstrual changes that hadn't been systematically assessed during development [6]. The menstrual cycle represents a complex, dynamic system with profound implications for health, human rights, and sociocultural and economic wellbeing [6]. This technical support document establishes core parameters requiring quantification and provides standardized methodologies to advance rigorous, reproducible research on menstrual cycle endpoints.

Core Parameters for Quantification

Cycle Length and Regularity Parameters

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) has established clinical standards defining normal and abnormal uterine bleeding, providing a critical foundation for research parameterization [6] [13]. These parameters should form the baseline for all clinical and research assessments.

Table 1: Core Menstrual Cycle Parameters and FIGO Definitions

| Parameter | FIGO Normal Range | Abnormal Classification | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle Frequency | Every 24-38 days | Short (<24 days) or long (>38 days) cycles | First day of one menses to first day of next |

| Bleeding Duration | ≤8 days | >8 days | Self-reported bleeding days |

| Cycle Regularity | Variation of ≤7-9 days between cycles | Variation >7-9 days | Standard deviation of consecutive cycle lengths |

| Bleeding Volume | "Normal" per patient assessment; no quality of life interference | Heavy (increases anemia risk) or light | Qualitative assessment; pictorial blood loss charts |

The follicular phase demonstrates substantially greater variability (15.7 ± 3 days; 95% CI: 10-22 days) compared to the luteal phase (13.3 ± 2.1 days; 95% CI: 9-18 days) [2]. Research indicates that 69% of variance in total cycle length is attributable to follicular phase variance, while only 3% stems from luteal phase variance [2]. This variability has profound implications for study design, particularly when testing interventions hypothesized to have phase-dependent effects.

Hormonal Parameters

Hormonal fluctuations represent the primary drivers of menstrual cycle changes, yet their measurement presents significant methodological challenges. The characteristic patterns of estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) across phases provide the biochemical foundation for cycle phase determination.

Table 2: Hormonal Parameters Across Menstrual Cycle Phases

| Cycle Phase | Estradiol (E2) Profile | Progesterone (P4) Profile | LH/FSH Status | Key Physiological Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Follicular | Low and stable | Consistently low | Baseline FSH | Menstrual bleeding |

| Late Follicular | Gradual rise then pre-ovulatory spike | Remains low | LH surge initiation | Cervical mucus changes |

| Ovulation | Dramatic peak | Begins gradual rise | LH peak, ovulation | Temperature shift onset |

| Early Luteal | Initial drop then gradual rise | Gradually rising | Post-surge decline | Sustained temperature elevation |

| Mid-Luteal | Secondary peak | Peaking levels | Low levels | Peak progesterone effects |

| Late Luteal | Rapid decline | Rapid decline | Low levels | Premenstrual symptoms |

Recent technological advances now enable more precise hormone monitoring through at-home urine tests that quantitatively track luteinizing hormone (LH) and pregnanediol-3-glucuronide (PdG), a urinary progesterone metabolite [14]. These methods represent significant improvements over traditional qualitative ovulation predictor kits.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Phase Verification and Ovulation Confirmation

Gold Standard Protocol for Phase Determination

For research requiring precise phase identification, the following multi-modal approach is recommended:

Initial Cycle Day Tracking: Document first day of menstruation (Cycle Day 1) through daily self-report.

Urinary Hormone Monitoring:

- Collect daily first-morning urine samples

- Quantify LH to detect the preovulatory surge (threshold: ≥2.5 times baseline)

- Measure PdG to confirm ovulation (threshold: ≥5 μg/mL for 3 consecutive days post-LH peak) [14]

Basal Body Temperature (BBT) Tracking:

- Measure immediately upon waking before any physical activity

- Document sustained temperature rise (≥0.3°C) for 3+ days confirming ovulation

Serum Hormone Validation (Optional):

- Draw serum samples 7-9 days post-LH surge for progesterone

- Threshold: P4 ≥10 nmol/L confirms ovulatory cycle [11]

Emerging Automated Methods

Machine learning approaches using wearable device data show promise for reducing participant burden in phase tracking. One recent methodology achieved 87% accuracy classifying three phases (period, ovulation, luteal) using random forest models with physiological signals including skin temperature, electrodermal activity, interbeat interval, and heart rate [15]. Another approach utilizing circadian rhythm-based heart rate (minHR) with XGBoost algorithms demonstrated particular robustness in individuals with high variability in sleep timing, outperforming BBT-based methods by reducing ovulation detection errors by 2 days [16].

Statistical Considerations for Menstrual Cycle Data

The menstrual cycle represents a fundamentally within-person process that must be treated as such in statistical modeling. Between-subject designs comparing groups in different cycle phases conflate within-subject variance (attributable to changing hormone levels) with between-subject variance (attributable to each person's baseline symptoms), producing invalid results [2].

Minimum Design Standards:

- Repeated Measures: At least 3 observations per person across one cycle to estimate random effects

- Multi-Cycle Assessment: 3+ observations across two cycles for reliable estimation of between-person differences in within-person changes

- Phase-Specific Sampling: Strategic assessment timing based on hormonal hypotheses (e.g., mid-follicular, periovulatory, mid-luteal for E2/P4 interaction effects)

Recommended Analytical Approaches:

- Multilevel modeling (random effects modeling) to account for nested data structure

- Circular statistics or harmonic regression for cyclic patterns

- Time-varying effect models for dynamic hormone-outcome relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Technologies for Menstrual Cycle Research

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application Notes | Evidence Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary LH Test Strips | Qualitative detection of LH surge | Inexpensive; limited to surge detection only | Well-validated for ovulation timing |

| Quantitative Urine Hormone Monitors (e.g., Oova, Mira) | Measures actual LH/PdG concentrations | Provides continuous hormone data; requires validation | Emerging evidence [14] [17] |

| Basal Body Temperature (BBT) Devices | Detects post-ovulatory progesterone rise | Affordable; confounded by sleep disturbances | Established but limited reliability |

| Wearable Sensors (e.g., Oura Ring, Empatica) | Continuous physiological monitoring (HR, HRV, temperature) | Reduces participant burden; machine learning analysis | Validation ongoing [15] |

| Menstrual Cycle Tracking Apps | Digital symptom and cycle day logging | Variable accuracy; depends on algorithm quality | Mixed validation results [17] |

| FIGO Bleeding Assessment Tool | Standardized bleeding characteristic documentation | Critical for uniform parameter assessment | Clinical gold standard [6] |

| Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS) | Diagnoses PMDD/PME from daily ratings | Eliminates retrospective recall bias | Validated against DSM-5 criteria [2] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do we accurately identify menstrual cycle phases in participants with irregular cycles?

Irregular cycles present significant methodological challenges. The recommended approach involves:

- Extending the data collection period to capture multiple cycles

- Implementing frequent (daily) hormone monitoring rather than phase-based sampling

- Using within-person standard deviations of cycle length to quantify irregularity

- Considering machine learning approaches that may be more adaptable to irregular patterns [15]

- Documenting potential causes of irregularity (energy balance, stress, medical conditions) [11]

Q2: What is the minimum number of cycles we should assess for reliable data?

The optimal number depends on research questions and outcome variability:

- For between-person differences in within-person changes: ≥2 cycles with 3+ observations each [2]

- For cycle characteristic stability (e.g., cycle length): ≥3 cycles to establish patterns

- For premenstrual disorder diagnosis: ≥2 symptomatic cycles required by DSM-5 [2]

Q3: How can we mitigate participant burden in intensive longitudinal designs?

- Utilize wearable technologies that passively collect physiological data [15]

- Implement smart notification systems rather than fixed-interval assessments

- Provide clear rationales for intensive sampling to enhance adherence

- Consider measurement-burst designs with intensive periods followed by rest

Q4: What validation methods are recommended for emerging menstrual tracking technologies?

- Conduct correlation studies with serum hormone measurements

- Compare phase identification against the multi-method gold standard

- Assess accuracy in diverse populations (including those with irregular cycles)

- Evaluate performance across the lifespan and in various health conditions [17]

Q5: How should we handle the confounding effects of hormonal contraceptives?

- Clearly document contraceptive type, formulation, and duration of use

- Consider excluding combined oral contraceptive users for studies of endogenous hormones

- For progestin-only methods, assess bleeding patterns rather than cycle phases

- Stratify analyses by contraceptive status when appropriate

Substantial methodological challenges persist in menstrual cycle research, including selection bias in study populations, measurement inconsistencies across studies, and insufficient attention to the within-person nature of cycle effects [8]. The parameters and methodologies outlined in this document provide a foundation for standardized approaches that will enhance cross-study comparability and accelerate knowledge generation. As the field advances, researchers must prioritize transparent reporting of methodological decisions, validation of emerging technologies, and inclusion of diverse populations to ensure findings generalize across the spectrum of menstrual experiences. Only through rigorous, standardized quantification of core menstrual cycle parameters can we overcome historical research gaps and advance both scientific understanding and clinical care for people who menstruate.

From Assumptions to Assays: A Toolkit for Direct Menstrual Cycle Phase Verification

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Category 1: Ultrasonography Challenges

Q: During follicle tracking, what does it mean if a dominant follicle is identified but then regresses without rupture?

- A: This is a classic sign of Luteinized Unruptured Follicle (LUF) Syndrome, a known methodological challenge in endpoint confirmation. The follicle matures and even begins luteinization (as evidenced by a subsequent progesterone rise) but fails to release the oocyte. This can lead to false-positive ovulation calls if relying solely on hormone data. Confirm with serum progesterone and ensure the ultrasound protocol continues until a corpus luteum (with its characteristic "ring of fire" on color Doppler) is visualized or menstruation occurs.

Q: Our ultrasound measurements of follicle size are inconsistent between operators. How can we standardize this?

- A: Inter-operator variability is a significant source of error. Implement this protocol:

- Training: Ensure all sonographers are trained to measure the mean diameter in the sagittal and transverse planes.

- Blinding: Operators should be blinded to the participant's cycle day and previous measurements when performing a scan.

- Calibration: Regularly calibrate ultrasound equipment.

- SOP: Use a strict Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) stating that follicle size is the average of three perpendicular diameters (longitudinal, anteroposterior, and transverse).

- A: Inter-operator variability is a significant source of error. Implement this protocol:

Category 2: Serum Hormone Profiling Issues

Q: We see an LH surge in our serum profiles, but no subsequent rise in progesterone. What is the likely cause?

- A: This pattern suggests an inadequate luteal phase or an anovulatory cycle. The hypothalamic-pituitary axis triggered an LH surge, but the resulting corpus luteum is failing to produce sufficient progesterone. This highlights the critical need for multi-parameter confirmation; an LH surge alone is not a definitive endpoint for a fertile ovulatory event. Review the entire hormone profile in context.

Q: Our assay for progesterone is producing high inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV), making it hard to define the post-ovulatory rise. How can we improve reliability?

- A: High CVs undermine data integrity. Troubleshoot as follows:

- Reagent Stability: Ensure all reagents, calibrators, and controls are within their expiration dates and have been stored correctly.

- Plate Layout: Use a randomized plate layout to avoid systematic bias. Include multiple internal controls across the plate.

- Sample Integrity: Confirm samples are not repeatedly thawed and refrozen. Use single-use aliquots.

- Assay Validation: Prior to the study, validate the assay for the specific matrix (e.g., serum) and expected concentration range.

- A: High CVs undermine data integrity. Troubleshoot as follows:

Category 3: Data Integration & Endpoint Definition

- Q: How do we definitively assign the day of ovulation (DOO) when hormone and ultrasound data are slightly discordant?

- A: There is no universal consensus, which is a core methodological challenge. You must pre-define a primary endpoint in your statistical analysis plan. The most common integrated definition is:

- The day of follicle disappearance (or a sudden decrease in size) is assigned as the DOO, provided it occurs within 24-48 hours after the LH peak. If the follicle disappears before the LH peak or more than 48 hours after, the cycle may be considered anovulatory or LUF for the study's purposes.

- A: There is no universal consensus, which is a core methodological challenge. You must pre-define a primary endpoint in your statistical analysis plan. The most common integrated definition is:

Table 1: Expected Hormone Levels Across the Peri-Ovulatory Period

| Cycle Phase | Luteinizing Hormone (LH) | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) | Estradiol (E2) | Progesterone (P4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late Follicular | Baseline (5-15 IU/L) | Baseline (5-10 IU/L) | Peak (>200 pg/mL) | Low (<1 ng/mL) |

| LH Surge | Surge (>25 IU/L) | Small parallel surge | Sharp decline | Begins to rise |

| Post-Ovulation | Drops to baseline | Drops to baseline | Low | Sustained rise (>3 ng/mL) |

Table 2: Follicular Growth and Morphological Changes via Ultrasonography

| Structure | Typical Size & Characteristics | Timing Relative to Ovulation |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant Follicle | Grows ~1.5-2.5 mm/day, reaches 17-28 mm before ovulation | -5 to -1 days before |

| Pre-Ovulatory Follicle | "Cumulus complex" may be visible on the wall. | -1 to 0 days before |

| Ovulation | Follicle suddenly collapses or disappears. Free fluid in pouch of Douglas may be seen. | Day 0 |

| Corpus Luteum | Irregular, cystic structure with "ring of fire" on color Doppler. | +1 to +2 days after |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Serial Transvaginal Ultrasonography for Follicle Tracking

- Participant Preparation: Participants should have an empty bladder for optimal visualization. Obtain informed consent.

- Equipment: Use a high-frequency transvaginal transducer (e.g., 5-9 MHz). Set machine to pre-defined gynecological settings.

- Scanning Procedure:

- Perform a systematic survey of the uterus and adnexa in both the sagittal and coronal planes.

- Identify and measure all follicles >10 mm in diameter in both ovaries.

- Measure each follicle in three perpendicular dimensions (longitudinal, anteroposterior, transverse). Record the mean diameter.

- Document the appearance of the follicle wall and the presence of any internal echoes or cumulus oophorus.

- Note the presence of free fluid in the pouch of Douglas.

- Frequency: Begin scans on cycle day ~8-10. Continue daily once a dominant follicle (>14 mm) is identified, until follicle rupture is confirmed.

Protocol 2: Serum Hormone Profiling via Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA)

- Sample Collection: Collect venous blood samples daily, synchronized with ultrasound scans. Allow blood to clot, then centrifuge to separate serum. Aliquot and freeze at -80°C.

- Assay Principle: The assay uses a biotinylated monoclonal antibody and a ruthenium-complex-labeled monoclonal antibody against the target hormone (e.g., LH, FSH, P4, E2). Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads capture the complex.

- Procedure:

- Thaw samples and reagents, bring to room temperature.

- Pipette 20 µL of calibrator, control, or sample into designated wells.

- Add the specific reagent mixture (biotinylated antibody + labeled antibody).

- Incubate for 9-18 minutes (time is assay-dependent).

- Apply a voltage to the electrode, inducing electrochemiluminescence.

- Measure light emission with a photomultiplier. Intensity is proportional to hormone concentration.

- Data Analysis: Use a 4- or 5-parameter logistic curve to interpolate concentrations from the calibrators.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: HPO Axis & Ovulation Pathway

Diagram 2: Ovulation Confirmation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Transvaginal Ultrasound Probe | High-frequency transducer for high-resolution imaging of ovarian follicles and endometrial lining. |

| ECLIA Reagent Kits (LH, FSH, P4, E2) | Ready-to-use kits for quantitative hormone analysis in serum, known for high sensitivity and wide dynamic range. |

| Biotinylated & Ruthenium-labeled Antibodies | Core components of the ECLIA; form the immunocomplex for specific hormone detection. |

| Streptavidin-coated Magnetic Beads | Solid phase for capturing the biotinylated antibody-hormone complex in the ECLIA. |

| Serum Separator Tubes (SST) | Tubes for blood collection that contain a gel separator for efficient serum recovery after centrifugation. |

| Hormone Calibrators & Controls | Essential for assay calibration and quality control to ensure inter-assay precision and accuracy. |

FAQ: Why use urinary metabolites like LH and PdG instead of serum hormones for menstrual cycle research?

Urinary hormone metabolites offer a non-invasive, practical method for field-based and at-home testing, enabling longer-term studies with higher compliance. Luteinizing Hormone (LH) in urine reliably detects the pre-ovulatory surge, while Pregnanediol Glucuronide (PdG), the primary urinary metabolite of progesterone, confirms ovulation has occurred [18]. Quantitative home-use devices can predict urinary hormone values that show high correlation with serum concentrations, providing a valid proxy for serum measurements in research settings [19].

FAQ: What are the primary methodological challenges in validating at-home hormone tests?

Key challenges include ensuring test-retest reliability and managing unexpected instrumentation failure [20]. Furthermore, menstrual cycle research itself faces inherent methodological issues such as selection bias (e.g., over-representation of women trying to conceive), cycle phase misclassification when using self-report alone, and a lack of standardization in endpoint measurements across studies [8] [21]. Validation requires demonstrating that the at-home tool can accurately capture hormone trends and defined cycle endpoints despite this variability.

Validation Data & Performance Tables

Independent studies have validated the performance of various at-home hormone monitoring systems. The data below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Correlation between Urinary Metabolites and Serum Hormones [19]

| Urinary Metabolite | Serum Hormone | Correlation (R²) | Sample Size (Data Points) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrone-3-glucuronide (E3G) | Estradiol (E2) | 0.96 | 73 |

| Pregnanediol Glucuronide (PdG) | Progesterone (P4) | 0.95 | 73 |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) | Serum LH | 0.98 | 73 |

Table 2: Ovulation Detection Rates in a Pilot Comparative Study [22]

| Monitoring System | Cycles with Detected LH Surge | Correlation with CBFM Peak Fertility |

|---|---|---|

| Clearblue Fertility Monitor (CBFM) | 94% | Benchmark |

| Premom LH Test System | 82% | R = 0.99 |

| Easy@Home (EAH) LH Test System | 95% | R = 0.99 |

Table 3: Assay Precision of a Novel Smartphone-Based Reader [23]

| Analyte | Average Coefficient of Variation (CV) |

|---|---|

| Pregnanediol Glucuronide (PdG) | 5.05% |

| Estrone-3-glucuronide (E3G) | 4.95% |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) | 5.57% |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To establish correlation between urinary metabolite concentrations measured by a home-use device and serum hormone levels.

Methodology:

- Participants: Recruit women of reproductive age (21-45) with regular cycle lengths (23-45 days). Exclude users of hormonal contraception, infertility medications, or those who are recently pregnant/breastfeeding.

- Sample Collection:

- Blood: Collect 2 ml venous blood samples in EDTA-coated vacutainers during assigned phases (early follicular, late follicular, luteal). Maintain a 10-12 hour fasting period prior. Analyze serum E2, P4, and LH using chemiluminescent immunoassays.

- Urine: Participants test first-morning urine at home using the fertility monitor on the same day as blood collection. Record test timings precisely.

- Data Analysis: Perform linear regression analysis to correlate serum hormone levels with device-predicted urinary metabolite values.

Objective: To compare the beginning, peak, and length of the fertile window as determined by a new LH tracking app versus an established fertility monitor.

Methodology:

- Design: Prospective, randomized pilot study.

- Participants: Women aged 18-42 with regular cycles, not using hormonal contraception or known to have fertility problems.

- Procedure:

- Randomize participants into groups using different LH test strips (e.g., quantitative Premom vs. qualitative Easy@Home).

- Instruct participants to test first-morning urine from cycle day 6 for 20 days over three cycles.

- On each test day, consecutively test urine with the CBFM test strip followed by the assigned LH test strip.

- Record results (low/high/peak for CBFM; quantitative/ratio for app-based strips) on a charting sheet.

- Analysis: Use Pearson correlation to compare the peak fertility day identified by the app systems with the CBFM peak day.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Erratic Hormone Readings

- Action 1 (Gather Information): Thoroughly document the unexpected readings. Check for participant compliance with testing protocols (e.g., first-morning urine, proper strip dipping time). Review any error logs or messages from the device [20].

- Action 2 (Identify Root Cause): Analyze potential sources. Common causes include diluted urine samples, improper test strip storage, device software glitches, or user error in reading results [22] [20].

- Action 3 (Resolve):

- Re-train participants on standardized collection procedures.

- Ensure test strips are stored in a cool, dry place and are not expired.

- Update device firmware or application software.

- For visual test strips, use a smartphone app for objective quantification to reduce user interpretation error [22].

Problem: Failure to Detect an LH Surge or PdG Rise

- Action 1 (Gather Information): Confirm the participant's cycle length and testing window. Review the complete cycle's data for any subtle shifts. Check if the participant has conditions like PCOS, which can cause multiple LH surges or anovulation [18].

- Action 2 (Identify Root Cause): The root cause could be a short LH surge that was missed between tests, an anovulatory cycle, or a PdG rise that is below the detection threshold of the test [18] [21].

- Action 3 (Resolve):

- Recommend testing twice daily (mid-morning and evening) as the LH surge approaches.

- Use a combination of methods (LH, PdG, BBT) to build a complete picture. A sustained BBT rise may indicate ovulation even if PdG is low, or a positive PdG test can confirm ovulation even if the LH surge was missed [18].

- If anovulation is suspected across multiple cycles, recommend clinical evaluation.

Problem: Suspected Instrument Malfunction

- Action 1 (Gather Information): Replicate the problem with a new test strip and a control solution if available. Document any error codes [24].

- Action 2 (Identify Root Cause): Follow a step-by-step approach. Isolate variables: try a different smartphone (for app-based devices), different batch of test strips, or different user [20] [24].

- Action 3 (Resolve):

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Validating Urinary Hormone Metabolites

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Quantitative LH Test Strips | Measures the surge of Luteinizing Hormone in urine to predict impending ovulation. Provides quantitative data for trend analysis [22]. |

| PdG (Pregnanediol Glucuronide) Test Strips | Confirms ovulation by detecting the rise in the primary urinary metabolite of progesterone during the luteal phase [23] [18]. |

| E3G (Estrone-3-glucuronide) Test Strips | Tracks the rise of estrogen in the follicular phase, helping to identify the start of the fertile window [23]. |

| Smartphone-Connected Reader / App | Provides objective, quantitative readouts of test strips, reducing user interpretation error and enabling digital data collection for analysis [22] [23]. |

| Electronic Hormonal Fertility Monitor (e.g., CBFM) | An established research tool that measures E3G and LH to provide "low," "high," and "peak" fertility readings, used as a benchmark for validation studies [22]. |

| Reference Standards (for E3G, PdG, LH) | Purified metabolites used to generate calibration curves for assay validation and to determine the accuracy and recovery percentage of testing systems [23]. |

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

Research Troubleshooting Logic Flow

Urinary Hormone Validation Workflow

For researchers and drug development professionals, the accurate measurement of menstrual cycle endpoints presents a significant methodological challenge. The menstrual cycle is a dynamic process characterized by complex, individual-specific hormonal fluctuations. Relying on assumed or estimated cycle phases, rather than direct physiological measurements, introduces substantial variability and risks generating low-quality evidence [1]. This technical resource center outlines how wearable devices and apps can provide objective, continuous data to overcome these challenges, while also addressing the practical troubleshooting issues that arise in a research setting.

Technical Support & FAQs for Research-Grade Wearables

Q1: Our research team is encountering low signal quality from wrist-worn PPG sensors. What steps can we take to improve data fidelity?

- A: Low photoplethysmography (PPG) signal quality is a common issue that can compromise heart rate and heart rate variability data. Implement the following protocol:

- Device Fit: Ensure the device is snug but not constricting. It should not slide on the wrist. For studies involving prolonged wear, use adjustable, hypoallergenic bands.

- Sensor Placement: The sensor must maintain consistent skin contact. Position it on the top of the wrist, proximal to the ulnar styloid process. Provide participants with clear pictorial guides.

- Activity Logging: Instruct participants to log periods of high-motion activity (e.g., typing, vigorous exercise) as these can introduce motion artifact. This metadata is crucial for post-processing and data cleaning.

- Data Quality Checks: Implement automated checks for signal-to-noise ratio. Define exclusion criteria a priori, such as segments where more than 20% of data is lost to artifact.

Q2: How can we validate that a wearable is accurately capturing menstrual cycle phases and not just sleep/wake cycles or activity patterns?

- A: Validation is a multi-step process requiring a combination of device data and gold-standard references:

- Multi-Modal Sensing: Utilize devices that capture multiple parameters (e.g., resting heart rate, heart rate variability, skin temperature, sleep data). Correlated fluctuations across several parameters strengthen the phase prediction [25] [15].

- Ground Truthing: For a subset of your cohort or a validation cycle, correlate wearable data with direct hormonal assays. This includes urinary luteinizing hormone (LH) tests to pinpoint ovulation and serum (or validated salivary) progesterone levels to confirm luteal phase status [1].

- Algorithm Transparency: When selecting a device or platform, inquire about the machine learning model used for phase prediction (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) and the features it relies on. Models using a combination of circadian-based heart rate features and cycle day have shown high accuracy [16].

Q3: What is the best practice for handling data from participants with irregular sleep patterns or shift work?

- A: Irregular sleep timing is a known confounder for metrics like Basal Body Temperature (BBT). Wearables can offer more robust solutions.

- Circadian Metrics: Leverage features that are less dependent on sleep timing. One study developed a model using the heart rate at the circadian rhythm nadir (

minHR), which significantly outperformed BBT in participants with high sleep timing variability, reducing ovulation day detection errors by two days [16]. - Sleep Stage Data: Use the device's sleep staging (awake, light, deep, REM) to identify the most quiescent periods for analysis, rather than relying on arbitrary clock times.

- Stratified Analysis: Plan to stratify your analysis based on sleep regularity metrics, which can be derived from the wearable data itself.

- Circadian Metrics: Leverage features that are less dependent on sleep timing. One study developed a model using the heart rate at the circadian rhythm nadir (

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent large-scale studies on cardiovascular fluctuations across the menstrual cycle, providing reference values for researchers.

Table 1: Population-Level Cardiovascular Metrics Across the Menstrual Cycle in Naturally Cycling Individuals (n=11,590) [25]

| Metric | Nadir (Lowest Point) | Offset from Cycle Mean | Peak (Highest Point) | Offset from Cycle Mean | Average Amplitude (Peak-Nadir) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting Heart Rate (RHR) | Day 4.81 | -1.83 BPM | Day 26.44 | +1.64 BPM | 2.73 BPM |

| HRV (RMSSD) | Day 27.13 | -3.22 ms | Day 4.81 | +3.57 ms | 4.65 ms |

Table 2: Performance of Machine Learning Models in Menstrual Phase Classification [16] [15]

| Study Model | Input Features | Classification Task | Accuracy | Key Validation Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost [16] | Cycle day + Heart Rate at Circadian Nadir (minHR) |

Luteal Phase vs. Follicular Phase | High (Specifics not given) | Outperformed BBT in high sleep variability; reduced ovulation error by ~2 days. |

| Random Forest (Fixed Window) [15] | HR, IBI, EDA, Temperature | 3 Phases (Period, Ovulation, Luteal) | 87% | AUC-ROC: 0.96; Leave-last-cycle-out cross-validation. |

| Random Forest (Sliding Window) [15] | HR, IBI, EDA, Temperature | 4 Phases (Period, Follicular, Ovulation, Luteal) | 68% | AUC-ROC: 0.77; Simulates real-world daily tracking. |

Experimental Protocols for Wearable-Based Endpoint Measurement

Protocol 1: Validating Menstrual Cycle Phase Classification

Objective: To establish a robust methodology for classifying menstrual cycle phases in a research cohort using wearable-derived data, validated against hormonal markers.

Materials: Research-grade wearable devices (e.g., Oura Ring, Empatica Embrace, Garmin watch) capable of continuous PPG and skin temperature monitoring; urinary LH test kits; saliva collection kits for progesterone assay; a digital platform for participant symptom logging.

Methodology:

- Participant Onboarding: Recruit participants meeting inclusion criteria (e.g., premenopausal, naturally menstruating). Define "naturally menstruating" as cycle lengths of 21-35 days, with no confirmed hormonal status, and "eumenorrheic" as meeting the same criteria with confirmed ovulation and sufficient progesterone [1].

- Data Collection: Continuous physiological data is collected via the wearable device for the duration of the study (minimum two complete cycles). Participants self-administer urinary LH tests daily from cycle day 10 until a surge is detected. Saliva samples for progesterone assay are collected in the mid-luteal phase (e.g., days 19-22).

- Phase Determination:

- Ovulation: The day after the positive urinary LH test is designated as ovulation day.

- Luteal Phase: Defined as the period from post-ovulation to the onset of next menses, confirmed by elevated progesterone levels in saliva.

- Follicular Phase: Defined as the period from menses onset to ovulation.

- Data Analysis: Machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest) are trained using features extracted from the wearable data (e.g.,

minHR, nightly average skin temperature, HRV). The model's phase classification output is validated against the ground-truth hormonal phase labels.

Protocol 2: Calculating Cardiovascular Amplitude as a Novel Endpoint

Objective: To derive and analyze the "cardiovascular amplitude" metric for investigating the magnitude of physiological fluctuation and its association with factors like age and hormonal birth control use.

Materials: Wrist-worn wearable device with PPG capabilities; a validated menstrual cycle tracking app.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Collect continuous RHR and RMSSD data across multiple complete menstrual cycles.

- Cycle Alignment: Align all cycle data to a standardized length (e.g., 28 days) or use the participant's actual cycle length, clearly stating the method.

- Amplitude Calculation:

- RHR Amplitude (RHRamp): For each cycle, calculate the mean RHR during the early cycle window (days 2-8, centered on the population nadir at day 5). Subtract this from the mean RHR during the late luteal window (the final 7 days of the cycle) [25].

- RMSSD Amplitude (RMSSDamp): Perform the same calculation for RMSSD (mean days 2-8 minus mean final 7 days).

- Cohort Analysis: Calculate the average RHRamp and RMSSDamp for each participant. Use generalized linear models to test for associations with age, BMI, and birth control status. As demonstrated, birth control pill use is associated with a significant attenuation of cardiovascular amplitude [25].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Wearable-Based Studies

Table 3: Key Materials and Tools for Menstrual Cycle Research Using Digital Technology

| Item | Function in Research | Example Products / Models |

|---|---|---|

| Research-Grade Wearables | Continuous, raw data collection of physiological signals (PPG, accelerometry, EDA, temperature). | Empatica EmbracePlus, E4 Wristband [15], Oura Ring [26] |

| Medical-Grade Wearables | FDA-approved devices for clinical endpoint monitoring (ECG, respiratory rate). | VitalPatch [26], BioBeat wearables [26] |

| Hormonal Assay Kits | Provide gold-standard validation for ovulation (LH) and luteal phase confirmation (Progesterone). | Urinary LH test kits (OTC), Salivary Progesterone ELISA Kits |

| Digital Logging Platforms | Secure collection of participant-reported outcomes (symptoms, medication) and ground-truth labels (menses onset). | Custom REDCap surveys, Commercial FDA-cleared apps |

| Data Analysis Software | Machine learning model training, statistical analysis, and data visualization. | Python (scikit-learn, XGBoost), R, MATLAB |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Research Workflow for Wearable-Based Endpoint Measurement

Wearable Data Processing for Research Endpoints

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core terminology change recommended for discussing menstrual changes in clinical trials? The consensus recommends a shift to patient-centered and accessible language. The term "Contraceptive-Induced Menstrual Changes (CIMCs)" should be prioritized to accurately describe the full range of user experiences, moving away from technical or potentially stigmatizing terms like "bleeding patterns." This ensures the language in trial protocols, data collection tools, and eventual product labeling is clear and meaningful to patients [27] [28].

Q2: How should we select a Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (PROM) for CIMCs? The selection process must be scientifically rigorous. The chosen PROM must be a validated instrument designed to measure a specific concept, such as symptoms or impacts on daily life [29]. For CIMCs, a disease-specific (in this case, condition-specific) PROM is strongly recommended over a generic one. This ensures the tool is relevant and responsive to the specific changes caused by contraceptives, includes items that matter to users, and avoids irrelevant questions that can lead to poor data quality [29]. The instrument should have evidence of proper development, validation, and testing for the intended population [29].

Q3: What are the key considerations for designing the data collection strategy? The consensus emphasizes standardized data collection of primary CIMC and acceptability outcomes [28]. Key recommendations include:

- Accounting for Confounders: The study design and recruitment strategy must consider intrinsic (e.g., age, BMI) and extrinsic factors (e.g., concomitant medications) that could influence menstrual outcomes [28].

- Harmonized Analysis: Pre-specify statistical analysis plans that use harmonized approaches, including how to handle the common challenge of missing data [28].

- Standardized Data Elements: Using Common Data Elements (CDEs), as demonstrated in other fields like circadian rhythm and stroke research, provides a framework for aggregation and comparison across studies [30].

Q4: Our trial uses electronic data capture. Are there standards for structuring this data? Yes. For regulatory submissions, implementing CDISC Foundational and Therapeutic Area Standards is often required. These standards provide models and specifications for data representation, facilitating data sharing, improving quality, and streamlining regulatory review [31]. This ensures your data on CIMCs and PROs is structured in a consistent, predictable format.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Endpoint Reporting Across Trial Sites

Problem: Investigator-reported events of abnormal bleeding or other CIMCs are inconsistent, with varying interpretations of definitions across different clinical sites, potentially introducing bias.

Solution: Implement a Central Endpoint Adjudication Committee (CAC).

- Background: Central adjudication is a standardized process for the independent, blinded assessment of safety and efficacy endpoints in clinical trials. It aims to achieve consistency and accuracy, reducing variability from site-based assessments [32].

- Procedure:

- Develop a Charter: Create a detailed charter that specifies the CAC's composition (e.g., clinical specialists in gynecology), operating procedures, and, most critically, the precise endpoint definitions for all CIMCs [32].

- Define Endpoints: Establish clear, objective criteria for different types of menstrual changes (e.g., amenorrhea, frequent bleeding, heavy bleeding) based on the consensus recommendations [28].

- Collect Source Documents: The Endpoint Office (EPO) collects relevant source documents (e.g., patient diaries, PRO questionnaires, clinical notes) for each potential event [32].