Assessing Public Awareness of Bisphenols, Phthalates, and Parabens: A Scientific Review for Research and Drug Development

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence on public awareness and exposure to prevalent endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs)—bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens.

Assessing Public Awareness of Bisphenols, Phthalates, and Parabens: A Scientific Review for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence on public awareness and exposure to prevalent endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs)—bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational science behind these compounds, methodologies for assessing public awareness and exposure, strategies for improving risk communication, and comparative analyses of regulatory and health outcome data. The review highlights significant awareness gaps despite widespread exposure, underscores the role of human biomonitoring (HBM) in exposure assessment, and discusses the implications of emerging substitutes and mixture toxicity for future biomedical research and public health policy.

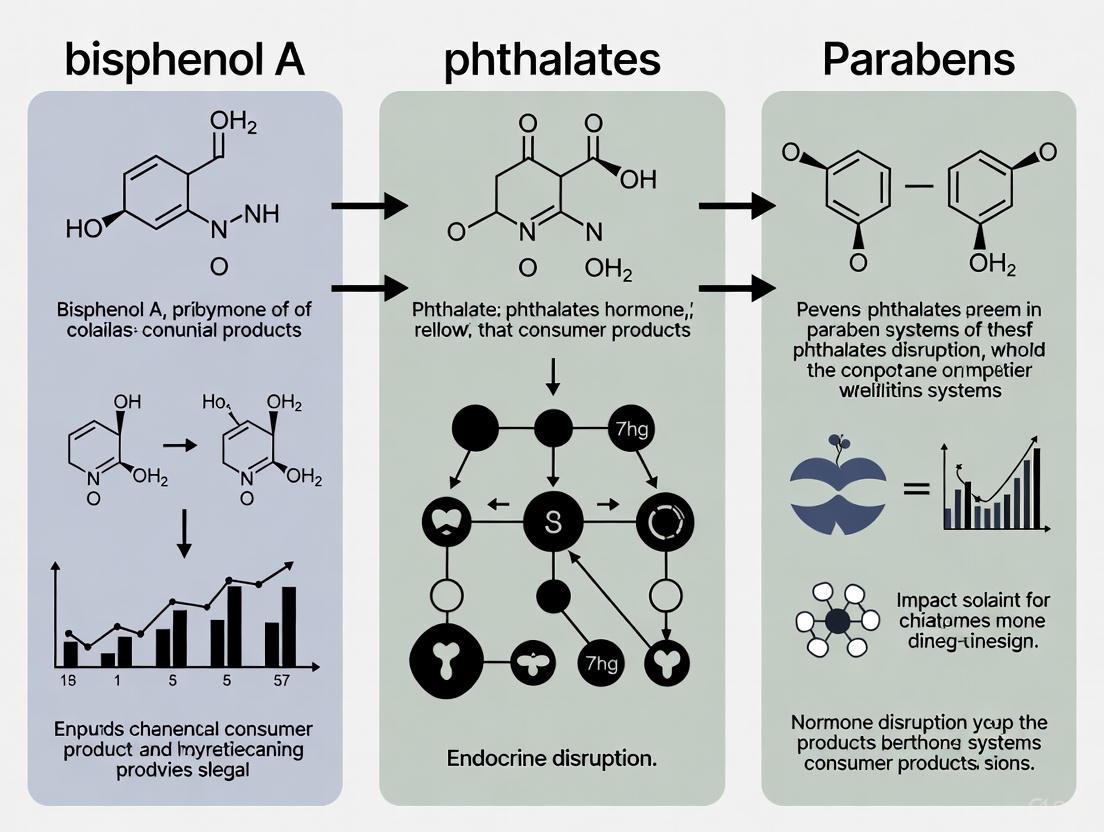

The Unseen Exposure: Foundational Science and Population Awareness of Common EDCs

Bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens represent three classes of synthetic chemicals that have become ubiquitous in modern industrial and consumer applications. Their widespread use as plasticizers, preservatives, and additives has led to pervasive environmental contamination and human exposure, raising significant concerns within the scientific and public health communities. Framed within a broader thesis on public awareness, this technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of these compounds, detailing their primary sources, environmental prevalence, analytical methodologies for their detection, and the molecular mechanisms underpinning their health impacts. Understanding the ubiquity and characteristics of these chemicals is a fundamental prerequisite for informed risk assessment and the development of effective mitigation strategies.

The following table delineates the core characteristics and common applications of bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens.

Table 1: Defining Bisphenols, Phthalates, and Parabens

| Chemical Class | Chemical Structure & Properties | Primary Functions & Uses | Common Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenols | Two hydroxyphenyl groups; key component in polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins [1]. | Production of polycarbonate plastics, epoxy resin linings for food/drink cans, thermal paper, medical devices, and dental sealants [2] [1]. | Bisphenol A (BPA), Bisphenol S (BPS), Bisphenol F (BPF), Bisphenol AF (BPAF), Bisphenol B (BPB), Bisphenol E (BPE) [1]. |

| Phthalates | Diesters of phthalic acid; not chemically bound to plastics, enabling leaching [3]. | Plasticizers to enhance flexibility, durability, and transparency of plastics (esp. PVC); also used as solvents and fragrance carriers [4] [5] [3]. | Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP), Diethyl phthalate (DEP), Di-isobutyl phthalate (DIBP), Benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP) [4] [3]. |

| Parabens | Esters of para-hydroxybenzoic acid; broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity [6] [7]. | Preservatives in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, food products, and personal care products to extend shelf-life [6] [7]. | Methylparaben (MeP), Ethylparaben (EtP), Propylparaben (PrP), Butylparaben (BuP) [6] [7] [8]. |

Environmental Ubiquity and Concentrations

The extensive use of these chemicals has resulted in their detection across diverse environmental matrices. The following tables summarize reported concentrations in aquatic environments, sediments, and human exposure markers.

Table 2: Environmental Concentrations of Bisphenols and Phthalates

| Matrix | Location | Chemical | Concentration Range | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Water | European freshwaters | Bisphenol A (BPA) | <0.03 ng/L - 588,000 ng/L (Median: 36 ng/L) | [9] |

| European saline waters | Bisphenol A (BPA) | <0.03 ng/L - 4,800 ng/L (Median: 22.2 ng/L) | [9] | |

| Turag River, Bangladesh (Rainy) | Bisphenol F (BPF) | 1.3950 - 7.2352 μg/L | [1] | |

| Turag River, Bangladesh (Winter) | Bisphenol F (BPF) | 1.1186 - 7.3094 μg/L | [1] | |

| Coastal Bushehr, Iran (Wastewater) | Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) | 19.67 - 39.75 μg/L | [4] | |

| Sediment | European freshwater | Bisphenol A (BPA) | <0.01 - 8,067 ng/g dry weight (Median: 78.5 ng/g) | [9] |

| Turag River, Bangladesh | Bisphenol F (BPF) | 27.2740 - 234.4540 μg/g dry weight | [1] | |

| Human Exposure | Urine Samples (General Population) | Bisphenol A (BPA) | [2] | |

| Urine Samples (General Population) | Bisphenol S (BPS) | [2] |

Table 3: Environmental Concentrations and Exposure of Parabens

| Matrix | Location | Chemical | Concentration / Level | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wastewater Influent | Various (Literature Review) | Total Parabens | 5460 - 10,000 ng/L (up to 79.6 μg/L) | [6] [7] |

| Groundwater | Rural Nigeria | Butylparaben (BuP) | Up to 400 μg/L | [8] |

| Human Exposure | Personal Care Product Users | Paraben Metabolites | Urinary levels 28-80% higher than non-users | [7] |

Detailed Analytical Methodologies

Accurate assessment of these contaminants requires robust and sensitive analytical protocols. The following section details specific experimental workflows cited in recent literature.

Analysis of Phthalate Esters (PAEs) and BPA in Wastewater

A study investigating contaminants in coastal wastewater employed the following protocol [4]:

- Sample Collection: Raw urban wastewater samples were collected in 100 mL pre-cleaned amber glass bottles and filtered through 0.45 μm nylon membrane filters to remove suspended particles.

- Extraction - Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE): For PAEs, 100 mL of filtered seawater was combined with 20 mL of dichloromethane and 20 μL of benzyl benzoate (internal standard) in a separatory funnel. The mixture was shaken vigorously to transfer PAEs into the organic phase.

- Extraction - Solid Phase Extraction (SPE): For BPA, 100 mL of acidified seawater (pH 2–3) was spiked with BPA-d16 (internal standard) and passed through pre-conditioned C18 cartridges.

- Instrumental Analysis - Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Analysis was performed using an Agilent 7890 GC/5975 MSD system with a J&W-5MS column. The oven temperature was programmed from 70°C (1 min hold) to 300°C at 10°C/min, with a 7 min final hold. Helium was used as the carrier gas at 1 mL/min.

Analysis of Bisphenol Analogues in River Water and Sediment

Research on an urban river system used this methodology for bisphenols [1]:

- Water Sample Extraction: A 500 mL water sample was salted with 150 g NaCl, acidified with HCl, and extracted with 20 mL of dichloromethane via mechanical shaking. The organic extract was dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and derivatized with BSTFA + 1% TMCS at 45°C for 30 minutes before GC-MS analysis.

- Sediment Sample Extraction: 10 g of homogenized sediment was extracted with 20 mL of DCM on an orbital shaker at 250 rpm for 60 minutes.

- Instrumental Analysis: The extracts were analyzed using GC-MS, with quantification performed against calibration curves of known bisphenol analogue standards.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing environmental contaminants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Environmental Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Amber Glass Bottles | Sample collection and storage; prevents photodegradation of target analytes. | Pre-cleaned with acetone, hexane, and methanol [4]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Extract and concentrate analytes from liquid samples. | C18 cartridges for BPA extraction [4]. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemically modify target analytes to improve volatility and detection for GC-MS. | BSTFA with 1% TMCS [1]. |

| Internal Standards | Correct for variability in extraction and analysis; enable accurate quantification. | Benzyl benzoate for PAEs; BPA-d16 for BPA [4] [1]. |

| Chromatography Columns | Separate complex mixtures of compounds within the instrument. | J&W-5MS ultra inert column (30 m × 0.25 mm I.D., 0.25 μm film) for GC-MS [4]. |

| Organic Solvents | Extraction and cleaning of samples. | Dichloromethane (DCM), acetone, hexane, methanol [4] [1]. |

Molecular Pathways and Health Significance

Epidemiological and toxicological studies have linked exposure to these chemicals with various adverse health outcomes, mediated through specific molecular pathways.

- Endocrine Disruption: Bisphenols and parabens can mimic natural estrogen by binding to estrogen receptors (ER), disrupting hormonal signaling [6] [7]. Phthalates are known to disrupt testosterone synthesis, which is a predictor of cardiovascular disease [5].

- Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: BPA exposure has been linked to childhood obesity by disrupting lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and inflammatory pathways [10]. Phthalates like DEHP contribute to heart disease by promoting inflammation in the coronary arteries [5].

- Specific Organ Toxicity: Phthalates accumulate in the kidneys, potentially causing renal inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer through mechanisms involving oxidative stress and activation of the PPARγ pathway [3]. Parabens have been detected in breast tumor tissues and are investigated for their potential role in breast cancer, possibly by interacting with the HER2 pathway [7].

Diagram 2: Key molecular pathways and health outcomes of chemical exposure.

Bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens are definitively established as ubiquitous environmental contaminants due to their extensive industrial and commercial applications. While European data suggests declining trends for BPA in some regions, the continued high levels found in other parts of the world and the increasing use of substitute compounds underscore a persistent and evolving issue. The health implications, driven by mechanisms such as endocrine disruption, oxidative stress, and inflammation, are supported by a growing body of scientific evidence. Enhancing public and professional awareness of the sources and prevalence of these chemicals is a critical first step toward mitigating exposure and informing future regulatory and research priorities.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), including bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens, have become ubiquitous in environment due to their widespread use in consumer products. Human exposure to these compounds is virtually unavoidable, occurring through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption [11]. These chemicals can interfere with the normal functioning of the endocrine system by mimicking, blocking, or altering the synthesis, transport, metabolism, or elimination of endogenous hormones such as estrogens, androgens, and thyroid hormones [12]. Understanding the routes of exposure and metabolic fate of these compounds is crucial for assessing health risks and developing public health strategies. This technical guide synthesizes current scientific knowledge on exposure pathways and bio-metabolism of these EDCs, providing researchers and public health professionals with essential information to advance both scientific understanding and public awareness.

Exposure Routes and Mechanisms

Dermal Absorption

Dermal exposure occurs when chemicals come into contact with skin and are absorbed into the bloodstream. The skin structure and chemical properties determine absorption efficiency.

- Mechanism: Dermal absorption is a two-step process involving contact between contaminant and skin, followed by absorption into the body. The amount absorbed represents what is available for interaction with target tissues or organs [13].

- Key Parameters: Dermal exposure depends on contaminant concentration in the contacted medium, timeframe of exposure, skin surface area exposed, and compound-specific permeability coefficients [13].

- Calculating Absorbed Dose: For inorganics in water, the internal absorbed dose can be calculated as: DAevent = Kp × C × t, where Kp is the permeability coefficient (cm/hr), C is the chemical concentration (mg/cm³), and t is contact time (hours/event) [13].

- Real-World Exposure: Feminine hygiene products have been identified as significant sources of EDC exposure in women, with panty liners containing the highest concentrations of dimethyl phthalate (median: 249 ng/g), diethyl phthalate (386 ng/g), dibutyl phthalate (393 ng/g), and di-iso-butyl phthalate (299 ng/g) [14]. Parabens are also frequently detected in bactericidal creams and solutions at parts per million levels [14].

Ingestion

Ingestion involves chemical absorption through the digestive tract, occurring both directly and indirectly.

- Direct Ingestion: Accidentally eating or drinking a chemical [15].

- Indirect Ingestion: Higher probability exposure occurs when food or drink is brought into contaminated environments or when people handle chemicals and then eat, drink, or smoke without proper hygiene [15].

- Primary Exposure Sources: Humans are mainly exposed to bisphenols through the diet, particularly from food packaging and canned food linings [16]. Some dairy products, fish, seafood, and oils have been found to contain high levels of phthalates [11].

- Vulnerable Populations: Infants are exposed to phthalates through breast milk from mothers exposed to DEHP and DiNP, and by sucking on toys containing DEHP, DBP, and BBP [11]. Phthalates can also cross the placenta-blood barrier, representing a major exposure route for the fetus [11].

Inhalation

Inhalation occurs when chemicals are absorbed through the respiratory tract (lungs), after which they can enter the bloodstream for distribution throughout the body.

- Forms Inhaled: Chemicals can be inhaled as vapors, fumes, mists, aerosols, and fine dust [15].

- Exposure Settings: Phthalates are semi-volatile organic compounds, with DEHP and DBP being the main compounds found in both indoor and outdoor air [11]. Residents living near phthalate manufacturing industries are particularly at risk through absorption of polluted air [11].

- Protection Measures: Laboratory workers can protect themselves through proper use of functioning fume hoods, dust masks, and respirators when fume hoods are not available [15].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Exposure Routes for Selected EDCs

| Chemical Class | Primary Exposure Routes | Common Sources | Vulnerable Populations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phthalates | Ingestion, Dermal, Inhalation | Plastic products, Personal care products, Food packaging, Medical devices | Fetuses, Infants, Children, Reproductive age adults [11] |

| Bisphenols | Primarily Ingestion | Canned food linings, Polycarbonate plastics, Thermal receipts | Pregnant women, Developing fetuses [16] |

| Parabens | Dermal, Ingestion | Cosmetics, Personal care products, Food packaging, Pharmaceuticals | Women (higher use of PCPs), Elderly [17] [16] |

Table 2: Concentration Ranges of EDCs in Various Exposure Media

| Exposure Medium | Phthalates | Parabens | Bisphenols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feminine Hygiene Products | DMP: 249 ng/g (median in panty liners); DEHP: 267 ng/g (median in tampons) [14] | MeP: 2840 ng/g; EtP: 734 ng/g; PrP: 278 ng/g (median in bactericidal creams) [14] | Not quantified in available studies |

| Human Serum | Not specified | MeP: 3.4 ng/mL (median in elderly) [17] | Not specified |

| Indoor Air | DEHP, DBP as main compounds [11] | Not specified | Not specified |

Metabolic Pathways and Fate

Phthalate Metabolism

Phthalates undergo rapid bio-metabolism in the human body, with short biological half-lives of approximately 12 hours [11]. The metabolic process occurs in two primary phases:

- Phase I Metabolism: The first step involves hydrolyzation after absorption into cells, where parent phthalate diesters are converted to their corresponding monoester metabolites [11].

- Phase II Metabolism: The second step is conjugation to form hydrophilic glucuronide conjugates, catalyzed by the enzyme uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronyl transferase [11].

- Metabolic Patterns: Metabolic pathways differ by phthalate type. Short-branched phthalates are typically hydrolyzed to monoester phthalates and excreted in urine, while long-branched phthalates undergo more complex transformations including hydroxylation and oxidation before excretion in urine and feces as phase 2 conjugated compounds [11].

- DEHP Metabolism: As an example of complex metabolism, DEHP is hydrolyzed to mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), which can then be further metabolized to mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate, mono(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate, mono(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate (MECPP), mono(2-carboxymethylhexyl) phthalate (MCMHP), and other metabolites [11].

- Excretion: Most phthalates and their metabolites are excreted in urine and feces, though some compounds (e.g., DEHP) and metabolites can also be excreted in sweat [11].

- Age-Related Differences: Research indicates that oxidative metabolism of DEHP is age-related, with younger children (6-7 years) excreting more oxidative DEHP metabolites compared to adults [11].

Bisphenol and Paraben Metabolism

Bisphenols and parabens are also rapidly metabolized, contributing to continuous exposure needs to maintain body burdens.

- Rapid Metabolism: Like phthalates, bisphenols and parabens are quickly metabolized in the body and do not bioaccumulate, with most metabolites excreted within 24 hours [18].

- Measurement Challenges: Due to this rapid metabolism, studies relying on single spot urine analyses may not accurately reflect exposure, as concentrations vary throughout a day and over longer periods [18].

- Enzymatic Transformation: Parabens (alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid) undergo metabolic hydrolysis and conjugation similar to phthalates [16].

- Interindividual Variability: Metabolic efficiency varies between individuals, potentially explaining differential susceptibility to EDC effects.

Figure 1: Integrated Exposure and Metabolic Pathway of EDCs

Experimental Methods for Exposure Assessment

Biomarker Measurement in Biological Samples

Accurate assessment of EDC exposure relies on sophisticated analytical methods to measure chemicals or their metabolites in biological samples.

- Sample Collection: Studies typically collect urine samples as the primary matrix for assessing exposure to non-persistent EDCs. The Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study protocol asked participants to collect all voids over a 24-hour period, with samples kept cool and frozen at −80°C within 36 hours of collection [19] [18].

- Analytical Techniques: Advanced chromatographic methods are employed:

- BPA Analysis: Total BPA (free plus conjugated) measured after enzymatic hydrolysis of urine samples, with derivation using pentafluorobenzyl bromide, extraction with hexane/dichloromethane mixture, and analysis by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry operating in negative chemical ionization mode [18].

- Phthalate Metabolite Analysis: Urine samples enzymatically hydrolyzed, with resulting phthalate monoesters extracted by anion exchange solid phase or liquid-liquid technique using hexane/ethyl acetate mixture, followed by analysis using tandem mass spectrometry with electrospray ion source in negative mode [18].

- Paraben Analysis: Measured using online solid-phase extraction coupled with isotope dilution–high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry [19].

- Quality Control: Implementation of strict quality controls including blank samples, low/medium/high concentration quality control samples, and careful treatment of labware to eliminate contamination [18].

- Specific Gravity Adjustment: Urine dilution is accounted for using specific gravity measurements with digital refractometers, with adjusted concentrations calculated using the formula: Pc = Pi × [(SGm - 1)/(SGi - 1)], where Pc is the adjusted concentration, Pi is the observed concentration, SGi is the sample specific gravity, and SGm is the median specific gravity for the cohort [18].

Dermal Exposure Assessment Protocol

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has established standardized approaches for assessing dermal exposure [13].

- Exposure Calculation: The average daily dermal dose (ADD) is calculated as: ADDabs = DAevent × SA × EF × ED / (BW × AT), where:

- DAevent = Absorbed dose per event (mg/cm²-event)

- SA = Skin surface area available for contact (cm²)

- EF = Exposure frequency (events/year)

- ED = Exposure duration (years)

- BW = Body weight (kg)

- AT = Averaging time (days)

- Dose Characterization: Differentiation between:

- Potential dose: Amount applied to skin

- Applied dose: Amount at absorption barrier

- Internal dose: Amount absorbed into bloodstream

- Biologically effective dose: Amount interacting with target tissues

- Permeability Coefficients: Use of empirically derived Kp values specific to chemical and vehicle matrix.

Table 3: Key Parameters for Dermal Exposure Assessment

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Description | Source Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permeability Coefficient | Kp | cm/hour | Chemical-specific skin permeability constant | Chemical-specific literature |

| Skin Surface Area | SA | cm² | Body region-specific surface area values | EPA Exposure Factors Handbook |

| Exposure Frequency | EF | events/year | How often exposure occurs | Product use surveys |

| Exposure Duration | ED | years | Length of exposure period | Study population characteristics |

| Body Weight | BW | kg | Body weight of exposed individual | Cohort measurements |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for EDC Exposure Assessment

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for EDC Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-labeled Standards | Internal standards for quantification | Deuterated phthalate metabolites for mass spectrometry [18] |

| Enzymes for Hydrolysis | Deconjugation of metabolites | β-glucuronidase for hydrolyzing phase II metabolites [18] |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample clean-up and concentration | Anion exchange SPE for phthalate metabolite extraction [18] |

| UPLC-MS/MS Systems | High-sensitivity analyte detection | Quantification of phenol and phthalate biomarkers [19] |

| Digital Refractometer | Specific gravity measurement | Urine dilution adjustment for exposure quantification [18] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Quality assurance and method validation | Quality control samples at low, medium, high concentrations [18] |

Implications for Public Awareness and Regulatory Science

The scientific evidence summarized in this review has significant implications for public awareness and regulatory policy. Understanding exposure routes and metabolic handling of EDCs provides the foundation for:

- Targeted Exposure Reduction: Identifying primary exposure routes enables development of specific intervention strategies, such as reducing use of certain personal care products or modifying food packaging materials.

- Biomonitoring Programs: Data on metabolic patterns informs selection of appropriate biomarkers for population surveillance studies.

- Risk Assessment Refinement: Quantitative exposure data and metabolic fate information support more accurate risk assessment and establishment of evidence-based safety guidelines.

- Public Health Communication: Clear understanding of exposure pathways enables more effective communication of practical risk reduction strategies to the public.

Future research should address critical knowledge gaps regarding cumulative effects of mixture exposures, sensitive windows of vulnerability, and interindividual differences in metabolism that may affect susceptibility to EDC-mediated health effects.

Biomonitoring Evidence of Widespread Exposure in General and Vulnerable Populations

Biomonitoring studies reveal widespread human exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs)—particularly bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens—across general and vulnerable populations. Recent national research demonstrates that 96 different chemicals were detected in US preschoolers, with 34 compounds found in over 90% of children [20]. These exposures are linked to potentially serious health implications, including disrupted reproductive function, altered hormonal balance, and adverse developmental outcomes [12] [21] [22]. Vulnerable populations such as children, pregnant women, and adolescents face disproportionate exposure and susceptibility due to their unique physiological characteristics and exposure patterns [20] [23] [24]. This technical review synthesizes current biomonitoring evidence, detailed methodological approaches, and emerging health associations to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in toxicology and public health.

Population-Specific Biomonitoring Data

General Population Exposure Profiles

Table 1: Biomonitoring Evidence of Widespread Exposure in General and Vulnerable Populations

| Population Group | Sample Size & Source | Key Chemicals Detected | Detection Frequency & Concentrations | Primary Exposure Routes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Preschoolers (2-4 years) | 201 children from ECHO Cohort [20] | 111 chemicals including phthalates, bisphenols, parabens, pesticides, OPEs, PAHs | 96 chemicals in ≥5 children; 48 in >50%; 34 in >90%; 9 not in NHANES [20] | Hand-to-mouth contact, indoor dust, food packaging, personal care products [20] |

| Adults (NHANES) | 4,455 US women (2005-2014) [25] | BPA, triclosan, benzophenone-3, methyl/ethyl/propyl/butyl paraben | BPA detected in >70% population; Triclosan Q2: OR=2.33 (1.45-3.75) for breast cancer [25] | Personal care products, food containers, pharmaceuticals [25] |

| Women Undergoing ART | 144 follicular fluid samples [21] | Phthalate metabolites (mPAEs), bisphenols, parabens, OH-PAHs | mPAEs highest (6.14 ng/mL), parabens (2.17 ng/mL), bisphenols (1.33 ng/mL), OH-PAHs lowest [21] | Dietary ingestion, dermal absorption, respiratory inhalation [21] |

| Pregnant Taiwanese Women | TMICS Cohort (2012-2016) [24] | Methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, BPA | Positive association makeup use & paraben levels; Higher BPA in lowest income group [24] | Leave-on PCPs (makeup, lotion), rinse-off products, food packaging [24] |

| Korean Adolescent Girls | 112 participants (13-17 years) [23] [26] | Methyl/ethyl/propyl parabens, BPA, benzophenones | Frequent PCP use → higher paraben levels; BPA reduced 32.7% post-intervention [23] | Skincare, sunscreen, cosmetics, lip products [23] |

Temporal Trends and Demographic Disparities

Longitudinal data from 2010-2021 reveals concerning exposure trends. While levels of triclosan, parabens, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and most phthalates have decreased, alternative plasticizers and emerging pesticides show significant upward trends [20]. Di-iso-nonyl-cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylic acid (DINCH), neonicotinoid acetamiprid, pyrethroid pesticides, and the herbicide 2,4-D have all demonstrated increasing detection frequencies [20].

Substantial demographic disparities exist in EDC exposure. Research indicates that firstborn children have significantly lower chemical levels than their younger siblings, and chemical concentrations are typically higher in 2-year-olds compared to 3- or 4-year-olds [20]. Importantly, children from racial and ethnic minority groups demonstrate higher levels of parabens, several phthalates, and PAHs, highlighting environmental justice concerns [20].

Socioeconomic status significantly modifies exposure patterns. Research with pregnant Taiwanese women found that lower income groups had higher BPA concentrations, particularly with frequent product use [24]. Conversely, the strongest associations between personal care product use and paraben concentrations were observed in the highest education group (postgraduate), suggesting product use patterns may vary by socioeconomic factors [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Biomonitoring Workflow and Analytical Techniques

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for biomonitoring studies of endocrine-disrupting chemicals:

Biomonitoring Workflow for EDC Assessment

Specific Analytical Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Extraction

For follicular fluid analysis, researchers employed rigorous sample preparation protocols. Internal standards were added to 200μL follicular fluid samples, followed by enzymatic hydrolysis using β-glucuronidase at 37°C for 180 minutes to deconjugate phase II metabolites [21]. The mixture was subsequently loaded onto MAX solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges, with target compounds eluted using 1 mL of 2% formic acid in methanol [21]. This protocol achieved recovery rates of 77%-109% for phthalate metabolites (mPAEs), 74%-97% for parabens, 63%-108% for bisphenols, and 64%-105% for hydroxylated PAHs (OH-PAHs) [21].

Instrumental Analysis

Separation and quantification employed ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). Specific analytical conditions varied by compound class:

- Parabens and phthalate metabolites were analyzed using a gradient of Milli-Q water and acetonitrile

- Bisphenols and OH-PAHs were analyzed using a gradient of 2 mM ammonium acetate and methanol [21]

Chromatographic separation utilized a Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 2.7 μm particle diameter) [21]. This methodology enabled precise quantification of compounds at concentrations as low as 0.1-2.3 ng/mL, depending on the specific analyte [25].

Quality Assurance and Quality Control

Each sample batch included procedural blanks, reagent blanks, and matrix-spiked samples for recovery assessment and background contamination evaluation [21]. For measurements below the limit of detection (LOD), values were assigned using established protocols: concentrations below LOD were treated as half the LOD value, while values between LOD and LOQ were calculated as one-fourth of the LOQ when detection frequencies were below 50%, or as one-half of the LOQ when detection frequencies exceeded 50% [21] [24].

Molecular Mechanisms and Health Implications

Endocrine Disruption Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the molecular mechanisms through which bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens disrupt endocrine function:

Molecular Mechanisms of EDC Action

Key Health Endpoints and Epidemiological Evidence

Reproductive Health Outcomes

Substantial evidence links EDC exposure to impaired reproductive function in both males and females. Systematic reviews of epidemiological studies demonstrate consistent associations between EDC exposure and multiple adverse reproductive endpoints, including impaired semen quality, decreased ovarian reserve, infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and altered hormone levels [12]. Research involving women undergoing assisted reproductive technologies (ART) reveals that EDCs measured in follicular fluid—the microenvironment surrounding developing oocytes—directly associate with alterations in critical reproductive hormones including estradiol (E2) and progesterone [21].

The specific mechanisms underlying these reproductive effects include:

- Disruption of Steroidogenesis: BPA exposure downregulates genes involved in ovarian steroidogenesis, disrupting hormone production and ovarian function [22]

- Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: BPA-induced oxidative stress damages reproductive tissues, while inflammation disrupts normal physiological processes in ovaries and testes [22]

- Epigenetic Modifications: BPA exposure induces DNA methylation changes in genes critical for ovarian function and follicular development, potentially contributing to transgenerational effects [22]

Developmental and Long-Term Health Risks

Early-life exposure to EDCs presents particular concern due to the heightened vulnerability during critical developmental windows. Research demonstrates that children have higher levels of several chemicals than their mothers during pregnancy, including two phthalates, bisphenol S (BPS), and pesticide biomarkers 3-PBA and trans-DCCA [20]. These early exposures may have lifelong consequences, as developmental exposure to EDCs has been linked to increased susceptibility to disease later in life, including hormone-sensitive cancers [25] and metabolic disorders [12].

Research Reagents and Methodological Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Tools for EDC Biomonitoring

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application in Research | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards | Parabens (MeP, EtP, PrP, BuP, HeP, BzP); Bisphenols (BPA, BPS, BPF, BPB, BPAF, BPZ, BPP, BPAP); OH-PAHs (1-hydroxynathalene, 2-hydroxynathalene, etc.); Phthalate metabolites (mPAEs) | Quantification and identification in biological matrices; Quality control and calibration | Purity ≥95%; Isotope-labeled internal standards for accurate quantification [21] |

| Sample Preparation | β-glucuronidase enzyme; MAX solid-phase extraction cartridges; Formic acid; Methanol, acetonitrile; Ammonium acetate | Enzymatic deconjugation; Sample purification and concentration; Mobile phase components | SPE recovery: 63%-109% depending on analyte; Enzymatic hydrolysis at 37°C for 180 min [21] |

| Chromatography | Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 2.7 μm); UPLC systems; C18 guard columns | Compound separation; Analytical separation with high resolution | Particle size: 2.7μm; Gradient elution with water/acetonitrile or ammonium acetate/methanol [21] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Triple quadrupole mass spectrometers; Electrospray ionization sources; Tandem mass spectrometry | Compound detection and quantification; High sensitivity detection | Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode; LODs: 0.1-2.3 ng/mL depending on analyte [21] [25] |

| Quality Control | Certified reference materials; Pooled quality control samples; Matrix-spiked samples | Method validation; Accuracy and precision assessment | Background contamination monitoring; Batch-to-batch reproducibility [21] |

Emerging Research Frontiers and Methodological Innovations

Novel Exposure Assessment Approaches

Recent studies demonstrate innovative methodologies for capturing complex exposure scenarios. Research integrating 7-day time-activity diaries with individualized urinary biomonitoring identified previously overlooked exposure sources, including medical plasters, sheer tights, wallpapering, vinyl flooring installation, and food preparation with gloves [2]. This approach revealed that standard questionnaires alone miss capturing diverse bisphenol exposure pathways, highlighting the need for more comprehensive exposure assessment strategies.

Mixture Effects and Advanced Statistical Models

Growing recognition of the "cocktail effect" of chemical mixtures has driven the development of advanced statistical approaches. Studies increasingly employ Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR), Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) regression, and Quantile g-computation to assess the combined effects of multiple EDCs [21] [27] [25]. These methods help identify the most influential chemicals in mixtures and characterize potential synergistic or antagonistic interactions.

BKMR analysis generates posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) to quantify individual chemical contributions, with a PIP threshold of 0.50 considered statistically significant [21]. Complementary analysis using Quantile g-computation models determines chemical-specific weight contributions, providing robust assessment of mixture effects that more accurately reflects real-world exposure scenarios.

Intervention Studies and Exposure Reduction Strategies

Intervention research demonstrates the efficacy of exposure reduction approaches. A 2-day cosmetic restriction intervention among Korean adolescent girls resulted in substantial reductions in BPA (32.7%) and benzophenones (11.9%-22.8%) after excluding participants with no baseline personal care product use [23]. This highlights the importance of targeted behavioral interventions for reducing EDC exposure in vulnerable populations, while also revealing the challenges in achieving significant reductions across all participants.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous compounds that interfere with the normal functioning of the hormonal system by mimicking, blocking, or altering the synthesis, transport, metabolism, or elimination of natural hormones [28]. The endocrine system is exceptionally vulnerable to disruption during critical developmental windows, and even low doses of EDCs can precipitate significant developmental and biological effects due to the hormone-sensitive nature of physiological processes [28]. Bisphenols (including BPA, BPS, and BPF), phthalates, and parabens represent some of the most pervasive EDCs in our environment, found in countless consumer products from food packaging and cosmetics to pharmaceuticals and toys [29] [28]. This technical review synthesizes current evidence linking these chemical classes to endocrine disruption, inflammatory responses, and subsequent chronic disease risks, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of mechanisms, outcomes, and methodological approaches.

Global Burden and Key Epidemiological Data

The global health burden attributable to EDC exposure has reached alarming proportions. A temporal and cross-country comparative analysis from 2000 to 2024 revealed a dramatic increase in metabolic diseases linked to bisphenol exposure alone, with cases rising from 68 million in 2000 to 127 million in 2024 [30]. This total includes 72 million cases of obesity, 24 million cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and 31 million cases of metabolic syndrome (MetS), with corresponding global economic costs projected to exceed $1.1 trillion USD in 2024 [30]. The distribution of this burden is not uniform, with Asia bearing 45% of the global bisphenol-related disease burden, followed by North America and Europe [30].

Table 1: Global Burden of Bisphenol-Attributable Metabolic Disease (2024)

| Health Outcome | Attributable Cases (Millions) | Primary Contributors |

|---|---|---|

| Obesity | 72 | BPS, BPF, BPA |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 24 | BPA, BPS |

| Metabolic Syndrome | 31 | BPA, BPF |

| Total | 127 |

Regulatory actions targeting specific EDCs have demonstrated complex outcomes. BPA-specific bans in Europe successfully reduced BPA exposure by 33%, but this achievement was offset by a 47% increase in BPS levels and a 22% increase in BPF exposure due to analog substitution [30]. Consequently, BPS and BPF now account for 76% of the global bisphenol-related disease burden, highlighting the phenomenon of "regrettable substitution" and the limitations of chemical-specific rather than class-based regulation [30].

Bisphenols: Metabolic and Reproductive Toxicity

Mechanisms of Action and Health Outcomes

Bisphenol A (BPA) and its analogs (BPS, BPF) primarily exert their endocrine-disrupting effects through interaction with estrogen receptors, particularly ESR1 and ESR2 [31] [32]. These interactions can alter gene expression related to steroidogenesis and metabolic homeostasis. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis represents a key target for bisphenol disruption, with downstream effects on reproductive function and development [31].

Recent research has revealed that co-exposure to bisphenols and other environmental contaminants can produce synergistic effects that exceed the toxicity of individual compounds. A 2025 study demonstrated that polyethylene microplastics (PE-MPs) can adsorb BPA, enhancing its bioavailability and environmental persistence [31]. When combined, PE-MPs and BPA induced significantly greater toxicity in MLTC-1 cells (mouse Leydig tumor cells) and zebrafish models compared to single exposures, decreasing cell viability, increasing apoptosis rates, inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest, and reducing mitochondrial membrane potential [31].

Gene Expression Alterations

In vivo studies using zebrafish models have documented sex-specific transcriptional changes following co-exposure to PE-MPs and BPA. In male zebrafish brains, genes including Gnrh2, Esr1, and Ar were downregulated, while in female brains, Gnrh3, Esr1, and Ar also exhibited downregulation [31]. In male testes, Star, Cyp11a1, and Hsd11b2 were upregulated, whereas Cyp19a1a, Hsd3b, Hsd20b, and Hsd17b3 were downregulated. Female ovaries showed upregulation of Cyp11a1, Cyp17, Cyp11b, Hsd3b, Hsd20b, and Hsd17b3, while Cyp19a1a was downregulated [31]. These findings demonstrate the capacity of bisphenols to disrupt critical reproductive pathways in a sex-specific manner.

Phthalates: Inflammatory Pathways and Immune Dysregulation

Metabolites and Systemic Inflammation

Phthalate metabolites (mPAEs) have emerged as significant modulators of inflammatory responses, with recent evidence pointing to their association with novel systemic inflammatory indices. A 2025 cross-sectional analysis of NHANES data from 2013-2018, encompassing 2,763 U.S. adults, employed multiple analytical models (generalized linear models, weighted quantile sum regression, Bayesian kernel machine regression, and restricted cubic splines) to investigate relationships between nine urinary phthalate metabolites and systemic immune inflammation index (SII) and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) [33].

The study identified mono-n-butyl phthalate (MnBP), mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP), and monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP) as being positively associated with SII/SIRI in single-exposure analyses [33]. In mixed-exposure models, mPAEs collectively showed a positive association with SII/SIRI, with MBzP identified as the most significant contributor [33]. These inflammatory indices integrate multidimensional information from neutrophils (pro-inflammatory), lymphocytes (immune regulation), platelets (coagulation/inflammation), and monocytes (chronic inflammation), providing a more systematic assessment of immune-inflammatory balance compared to conventional single-marker approaches [33].

Susceptible Populations

Subgroup analyses revealed that associations between mPAEs and SII/SIRI were more pronounced in specific demographic groups: females, overweight/obese populations, young/middle-aged adults, and individuals with high intake of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) [33]. This pattern highlights the importance of considering effect modification by lifestyle and demographic factors in EDC risk assessment.

Parabens: Metabolic Disruption and Carcinogenic Potential

Metabolic Perturbations

Parabens, commonly used as preservatives in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and food products, demonstrate significant potential for metabolic disruption, particularly in vulnerable populations. A 2025 nontargeted metabolomics study investigating paraben exposure in geriatric serum found that methyl paraben (MeP) and propyl paraben (PrP) were detected at high rates and concentrations in elderly individuals, with median MeP concentrations reaching 3.4 ng/mL [17]. The analysis identified 160 metabolites associated with paraben exposure, with steroid hormone biosynthesis and fatty acid metabolism emerging as the most significantly enriched pathways [17].

Molecular docking studies provided mechanistic insights into these metabolic disruptions, revealing that parabens can bind to and potentially inhibit 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD), a key enzyme in steroid metabolism [17]. This interaction represents a plausible molecular initiating event in paraben-induced metabolic syndrome and reproductive toxicity.

Estrogenic Activity and Breast Cancer Risk

Network toxicology approaches integrating molecular docking have elucidated potential mechanisms linking paraben exposure to breast carcinogenesis. Parabens exhibit estrogenic activity by binding to estrogen receptors (ESR1 and ESR2), potentially disrupting hormonal homeostasis and increasing breast cancer risk [32]. Additional analyses identified SERPINE1 as another core target in paraben-associated breast cancer pathogenesis [32].

Immune infiltration analyses further revealed that in breast cancer contexts, ESR1 expression was negatively correlated with CD8+ T cells and macrophages, while ESR2 and SERPINE1 expressions showed positive correlations with these immune populations [32]. Molecular docking confirmed strong binding activities between parabens and these core targets, suggesting a multifactorial mechanism involving direct receptor binding and immune modulation [32].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for EDC Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| MLTC-1 Cells (Mouse Leydig Tumor Cells) | In vitro steroidogenesis assessment | Evaluating combined toxicity of PE-MPs and BPA [31] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Model | In vivo endocrine disruption studies | HPG axis gene expression analysis after 28-day exposure [31] |

| NHANES Biomonitoring Data | Epidemiological studies | Cross-sectional analysis of phthalate metabolites and inflammation indexes [33] |

| Raman Spectrometry | Microplastic characterization | Physical characterization of PE-MPs [31] |

| Non-targeted Metabolomics | Metabolic pathway disruption screening | Identifying paraben-associated metabolic changes in geriatric serum [17] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Mechanistic binding studies | Predicting paraben interactions with ESR1, ESR2 [32] |

| CCK-8 Assay Kit | Cell viability assessment | Measuring cytotoxicity of BPA and PE-MPs in MLTC-1 cells [31] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Combined Toxicity Assessment

A comprehensive protocol for assessing the combined toxicity of microplastics and bisphenols exemplifies contemporary approaches to EDC research [31]:

Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Maintain MLTC-1 cells in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

- Prepare stock solutions of PE-MPs (average diameter 20 μm) and BPA, with working solutions diluted in culture media.

- Ensure uniform distribution of PE-MPs by vortex mixing and brief sonication of stock solution prior to dilution.

- Maintain DMSO concentration below 0.1% in all treatments and include vehicle control with equivalent DMSO concentration.

Viability Assay:

- Seed cells at density of 1 × 10^5 cells/well in 96-well plates.

- Expose cells to varying concentrations of BPA (0, 1, 10, 100, 150, 200, and 250 μmol/L) and PE-MPs (0, 10, 100, 1000 μg/mL) for 24, 48, and 72 hours.

- Add 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent to each well and incubate for additional 2 hours.

- Measure absorbance at 450 nm using plate reader, normalizing relative optical density against untreated controls.

Gene Expression Analysis:

- Extract total RNA from treated cells or harvested zebrafish tissues using appropriate isolation kits.

- Conduct reverse transcription followed by quantitative real-time PCR.

- Analyze expression of key genes related to steroidogenesis (Star, Cyp11a1, Hsd3b) and hormonal receptors (Ar, Esr1, Esr2).

- Normalize expression to appropriate housekeeping genes and calculate relative expression using 2^(-ΔΔCt) method.

Statistical Analysis Framework for Epidemiological Studies

Recent phthalate research demonstrates sophisticated analytical approaches for complex EDC mixture data [33]:

- Employ generalized linear models (GLM) to assess single-chemical associations between phthalate metabolites and inflammatory indices.

- Utilize weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression to evaluate the overall effect of phthalate mixtures and identify major contributors.

- Implement Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) to capture potential nonlinear and interaction effects in mixed exposures.

- Apply restricted cubic splines (RCS) to visualize dose-response relationships.

- Conduct extensive sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses to assess robustness of findings across demographic and lifestyle factors.

Visualizing Molecular Pathways and Experimental Workflows

EDC Mechanisms and Inflammatory Signaling

Integrated EDC Research Workflow

The accumulating evidence unequivocally demonstrates that bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens contribute significantly to endocrine disruption, inflammatory pathogenesis, and chronic disease risk through multiple interconnected mechanisms. The global health burden attributable to these chemicals is substantial and continues to grow, with recent data indicating 127 million cases of metabolic disease linked to bisphenol exposure alone in 2024 [30]. Future research directions should prioritize the development of class-based regulatory strategies that address all bisphenol analogues rather than individual compounds [30], increased focus on mixture effects and synergistic interactions [31], implementation of advanced biomonitoring and epidemiological designs to capture long-term exposure effects, and translation of mechanistic insights into targeted therapeutic approaches for EDC-associated conditions. For drug development professionals, understanding these pathways creates opportunities for interventions that might mitigate EDC effects, particularly for populations with high exposure burden.

Identifying Critical Knowledge Gaps in Public Understanding

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), including bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and parabens, constitute a significant public health concern due to their pervasive presence in consumer products and potential to interfere with hormonal systems. A comprehensive thesis on public awareness must acknowledge that while scientific evidence linking these chemicals to adverse health outcomes continues to grow, significant disparities exist between scientific understanding and public knowledge. This technical guide systematically identifies and characterizes the critical gaps in public understanding of BPA, phthalates, and parabens, providing a structured framework for researchers and public health professionals to develop targeted interventions. The analysis presented herein is synthesized from current epidemiological studies, social science surveys, and experimental research, offering a multi-dimensional perspective on the public awareness landscape.

Quantitative Assessment of Public Knowledge Gaps

Recent studies across multiple countries have quantified awareness levels for specific EDCs, revealing substantial knowledge gaps within the general public and vulnerable populations. The data demonstrates significant variability in recognition of different chemical substances, with historical contaminants better recognized than those prevalent in personal care products.

Table 1: Public Awareness Levels for Specific EDCs Across Populations

| Chemical | Population Studied | Awareness Level | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead | Women in Toronto (age 18-35) | Among most recognized EDCs | [34] |

| Parabens | Women in Toronto (age 18-35) | Among most recognized EDCs | [34] |

| Triclosan | Women in Toronto (age 18-35) | Among least recognized EDCs | [34] |

| Perchloroethylene | Women in Toronto (age 18-35) | Among least recognized EDCs | [34] |

| EDCs (general) | Pregnant women/new mothers, Türkiye | 59.2% unfamiliar | [35] |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Pregnant women/new mothers, Türkiye | Significant portion never heard | [35] |

| Phthalates | Pregnant women/new mothers, Türkiye | Significant portion never heard | [35] |

| Parabens | Pregnant women/new mothers, Türkiye | Relatively higher awareness | [35] |

| Phthalates | Irish residents (non-experts) | Lower perceived harmfulness | [36] |

| Parabens | Irish residents (non-experts) | Lower perceived harmfulness | [36] |

| PFAS | Irish residents (non-experts) | Lower perceived harmfulness | [36] |

Table 2: Relationships Between Knowledge, Demographics, and Behavioral Outcomes

| Factor | Impact on Awareness/Behavior | Population | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Education | More likely to avoid lead | Women with chemical sensitivities | [34] |

| Greater Knowledge of Specific EDCs | Significantly predicted chemical avoidance | Women (preconception/conception) | [34] |

| Higher Risk Perceptions | Predicted greater avoidance of parabens, phthalates | Women in Toronto | [34] |

| Label Reading | Associated with mitigated exposure | Reproductive-aged women | [34] |

| Awareness of Health Risks | Did not consistently translate to avoidance | Reproductive-aged women (only 29% adopted avoidance) | [34] |

Critical Knowledge Domains with Significant Gaps

Understanding of Regulatory Frameworks and Exposure Pathways

A fundamental gap identified in recent research concerns public misunderstanding of chemical regulations and exposure mechanisms. A U.S. survey revealed that most participants held significant misconceptions about regulatory oversight, with 82% incorrectly believing that chemicals must be safety-tested before being used in products, 73% wrongly assuming that product ingredients must be fully disclosed, and 63% mistakenly thinking that restricted chemicals cannot be replaced by similar substitutes [37]. This "false security" perception creates a critical barrier to informed consumer decision-making and public support for stronger regulatory measures.

Additionally, understanding of exposure pathways remains incomplete. While participants demonstrated some awareness of exposure routes (58-86%), comprehensive knowledge of how EDCs migrate from products to the human body remains limited [37]. This includes insufficient understanding of dermal absorption from personal care products, leaching from food packaging, and indoor air contamination from household goods.

Awareness of Health Implications and Vulnerable Populations

The public demonstrates partial understanding of the health implications associated with EDC exposure. While major health effects like impaired fertility (90% awareness), cancer risk (90%), and child brain development impacts (84%) were reasonably recognized [37], knowledge of specific mechanistic pathways and endocrine disruption mechanisms remains limited.

Critical gaps exist in understanding the heightened vulnerability during specific life stages, including fetal development, puberty, and reproductive years. Although pregnant women and new mothers represent a particularly vulnerable population, 59.2% of these women in one study were unfamiliar with EDCs generally [35]. This is especially concerning given evidence that EDCs can disrupt reproductive function by altering hormone levels, including estradiol (E2), luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) [12] [21].

Disconnect Between Awareness and Behavioral Change

Perhaps the most significant gap identified is the disconnect between awareness and protective action. Research indicates that even when individuals possess knowledge of EDC risks, this infrequently translates into consistent avoidance behaviors. Among reproductive-aged women aware of risks, only 29% adopted avoidance behaviors [34]. This intention-behavior gap represents a critical challenge for public health interventions.

Consumer behavior research indicates that avoidance strategies are more effective for certain chemicals than others. Individuals who reported avoiding specific ingredient groups (parabens, triclosan, bisphenols, and fragrances) were twice as likely to be in the lowest quartile of cumulative exposure [38]. However, avoiding BPA alone was not effective for reducing overall bisphenol exposure, likely due to substitution with analogous chemicals like BPS and BPF [38].

Methodological Approaches for Assessing Knowledge Gaps

Survey-Based Assessment Protocols

Standardized questionnaires represent the primary methodology for quantifying public knowledge gaps. The Health Belief Model (HBM) has been effectively employed to structure assessments of knowledge, health risk perceptions, beliefs, and avoidance behaviors [34]. A typical implementation includes:

Instrument Design: Developing structured questionnaires with sections on:

- Sociodemographic characteristics

- Knowledge assessment (access to resources, perceived sufficiency of knowledge)

- Health risk perceptions (perceived susceptibility and severity)

- Beliefs about health impacts

- Avoidance behaviors and purchasing practices

Measurement Scales: Utilizing Likert scales (typically 5- or 6-point) ranging from "Strongly Agree" to "Strongly Disagree" for knowledge, perceptions, and beliefs, and frequency scales ("Always" to "Never") for avoidance behaviors [34].

Sampling Strategy: Targeting specific populations (e.g., women aged 18-35 for reproductive health studies) with inclusion/exclusion criteria based on age, gender, and language proficiency [34]. Sample sizes should be calculated for adequate statistical power, with typical studies requiring 300-400 participants to detect awareness frequencies with 95% power and 5% alpha [35].

Implementation: Administration through both in-person recruitment (e.g., at relevant public events) and online platforms (e.g., Google Forms) to enhance participation diversity [34].

Biomonitoring-Coupled Behavioral Assessment

Innovative methodologies combine biological exposure monitoring with behavioral surveys to objectively measure the effectiveness of avoidance behaviors:

Study Design: Crowdsourced biomonitoring approaches recruit participants through open enrollment, targeting diverse populations without restrictive criteria [38].

Exposure Assessment: Collection of urine samples analyzed using:

- Solid-phase extraction combined with high-performance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS)

- Creatinine correction to normalize metabolite concentrations

- Lower limits of detection (LLODs) typically ranging from 0.10-2.30 ng/mL depending on the compound and analytical year [25]

Behavioral Correlation: Survey instruments capturing:

- Consumer product usage patterns

- Cleaning habits

- Specific chemical avoidance behaviors

- Ingredient label reading practices

Data Analysis: Multivariable regression models examining associations between 68+ self-reported exposure behaviors and urinary concentrations of ten+ target chemicals [38]. Evaluation of whether associations are modified by intention to avoid exposures.

Focus Group and Mental Models Approach

Qualitative methodologies provide depth and context to quantitative findings:

Focus Group Convening: Assembling community-engaged research teams (n=38) to define targets for public understanding [37].

Mental Models Approach: Structured facilitation including:

- Transcript coding and thematic analysis

- Causal pathway mapping of factors influencing EDC exposures and health outcomes

- Identification of key communication priorities based on expert consensus

Knowledge Gap Identification: Comparison between expert mental models and public knowledge through subsequent quantitative surveys to identify specific misconceptions and understanding gaps [37].

Experimental Workflows and Analytical Techniques

Biomarker Analysis in Biological Matrices

Advanced analytical techniques enable quantification of EDCs and their metabolites in various biological matrices to assess exposure levels:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EDC Analysis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Specification Example |

|---|---|---|

| MAX Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Extract and purify target analytes from complex biological matrices | 10 mg/1 mL capacity [21] |

| UPLC-Tandem Mass Spectrometry | Separate, identify, and quantify chemical concentrations | Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 2.7 μm) [21] |

| β-glucuronidase | Enzymatic deconjugation of phase II metabolites | Incubation at 37°C for 180 min [21] |

| Internal Standards | Isotope-labeled analogs for quantification accuracy | Deuterated compounds for each analyte class [21] |

| Mobile Phases | Chromatographic separation | Milli-Q water, acetonitrile, 2mM ammonium acetate, methanol [21] |

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Addition of Internal Standards: Spike samples with isotope-labeled internal standards for quantification accuracy [21]

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Incubate with β-glucuronidase at 37°C for 180 minutes to deconjugate metabolites [21]

- Solid-Phase Extraction: Load samples onto MAX SPE cartridges, elute targets using 1 mL of 2% formic acid in methanol [21]

- Chromatographic Separation: Utilize gradient elution with specific mobile phase combinations tailored to analyte classes [21]

- Mass Spectrometric Detection: Employ multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for sensitive and specific quantification [21]

Quality Assurance/Control Measures:

- Include procedural blanks, reagent blanks, and matrix-spiked samples in each batch

- Acceptable recovery rates: 63%-109% depending on analyte class [21]

- Values below LOD handled through standardized imputation protocols [25]

Mixture Risk Assessment Methodologies

Modern exposure science has developed sophisticated approaches to assess the effects of chemical mixtures:

Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR):

- Models complex exposure-response relationships for mixtures

- Generates posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) to quantify individual chemical contributions (PIP > 0.50 significant) [21]

- Allows visualization of multivariable exposure relationships

Quantile g-Computation (Qgcomp):

- Determines chemical-specific weight contributions in mixtures

- Estimates overall mixture effect direction and magnitude [27]

Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) Regression:

- Identifies potentially influential chemicals in mixtures

- Handles high correlation between exposures [27]

Figure 1: EDC Mixture Risk Assessment Workflow

Implications for Public Health Intervention and Research

The identified knowledge gaps present both challenges and opportunities for public health initiatives. Research indicates that current regulatory labeling practices insufficiently protect consumers, as terms like "fragrance" or "parfum" can mask dozens to hundreds of undisclosed chemical ingredients, even in products marketed as "green" or "eco-friendly" [34]. This underscores the need for enhanced ingredient transparency alongside educational efforts.

Effective intervention strategies should address the specific gaps identified in this analysis:

- Targeted Educational Campaigns: Focus on chemicals with lowest recognition (triclosan, perchloroethylene) and populations with identified vulnerabilities [34]

- Regulatory Knowledge Integration: Address misconceptions about chemical regulation and safety testing [37]

- Behavioral Implementation Strategies: Bridge the awareness-behavior gap through practical guidance on effective avoidance strategies [38]

- Knowledge Translation Tools: Develop mobile applications and educational toolkits with features including accessibility, information simplicity, personalization, and clear knowledge sharing [39]

Future research directions should prioritize longitudinal studies to assess knowledge evolution over time, evaluation of intervention effectiveness, and investigation of knowledge-behavior relationships across diverse socioeconomic and cultural contexts. Furthermore, integration of public perception data into chemical prioritization processes for biomonitoring programs represents a promising approach for aligning scientific and public health priorities [36].

From Urine to Survey: Methodological Approaches in Exposure and Awareness Assessment

Human Biomonitoring (HBM) serves as a gold-standard method for assessing human exposure to environmental chemicals by quantitatively measuring the parent compounds, their metabolites, or reaction products in biological tissues and fluids. For endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens—substances of significant public concern due to their prevalence in personal care products and food packaging—HBM provides critical data for linking exposure to health risks. This technical guide details the advanced analytical techniques, including liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), that enable the precise identification and quantification of these compounds at trace levels. It further explores the role of HBM data in elevating public awareness by translating complex exposure science into actionable evidence for policymakers and consumers, thereby informing risk assessment and regulatory strategies aimed at protecting vulnerable populations.

Human Biomonitoring (HBM) is a critical public health tool that directly measures the concentration of environmental chemicals or their metabolites in human biological specimens, such as urine, blood, and serum. By providing an integrated measure of exposure from all routes—including ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption—HBM offers an accurate and individualized assessment of a person's or population's internal dose of specific chemicals [40] [36]. This approach is widely regarded as the gold standard for exposure assessment because it accounts for variations in physiology, behavior, and multiple exposure pathways that indirect environmental monitoring cannot capture.

The application of HBM is particularly vital for assessing exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), such as bisphenols, phthalates, and parabens. Public awareness of the potential health risks from these chemicals, which are ubiquitous in consumer products, has grown significantly. HBM data transforms this awareness from a theoretical concern into an evidence-based one. For instance, national surveys like the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) have detected numerous EDCs in a majority of participants, providing tangible proof of widespread exposure that commands public and regulatory attention [20] [25]. Furthermore, HBM initiatives such as the European HBM4EU project have prioritized these substance groups, systematically evaluating exposure biomarkers and analytical methods to generate comparable data across borders, which is essential for effective public health policy [41].

Analytical Techniques for Major EDC Classes

The accurate quantification of EDCs and their metabolites in complex biological matrices requires sophisticated instrumentation and meticulously optimized methods. The following sections and tables detail the standard analytical approaches for the major classes of EDCs, highlighting the targeted biomarkers, preferred biological matrices, and key instrumental parameters.

Table 1: Analytical Techniques for Bisphenols, Phthalates, and Parabens

| EDC Class | Primary Biomarkers | Preferred Biological Matrix | Core Analytical Technique | Key Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenols | BPA, BPS, BPF (parent compounds) | Urine | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) | Often requires enzymatic deconjugation of glucuronidated metabolites; high sensitivity required for low ng/mL levels [41] [25]. |

| Phthalates | Monoester metabolites (e.g., MEP, MnBP, MEHHP, MEOHP) | Urine | LC-MS/MS | Measures metabolites to avoid contamination; specific metabolites like MEP are key biomarkers for personal care product exposure [41] [42]. |

| Parabens | Methylparaben (MPB), Ethylparaben (EPB), Propylparaben (PPB), Butylparaben (BUP) | Urine | LC-MS/MS | Typically analyzed as free compounds; creatinine correction is essential for normalizing urinary dilution [25] [24]. |

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Other Priority Chemicals

| EDC / Chemical Class | Primary Biomarkers | Preferred Biological Matrix | Core Analytical Technique | Key Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) | Parent compounds (e.g., PFOA, PFOS) | Serum | LC-MS/MS | Protein-binding chemicals require serum; methods require high sensitivity to detect pg/mL to ng/mL levels [41]. |

| Organophosphate Flame Retardants (OPFRs) | Metabolites (e.g., BDCPP from TDCPP) | Urine | LC-MS/MS with APCI or ESI | Metabolite measurement is specific for exposure assessment; BDCPP is a unique biomarker for TDCPP [41] [43]. |

| Metals (e.g., Cd, Cr) | Cadmium (Cd), Chromium (Cr) | Blood, Urine, Erythrocytes | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Measurement in erythrocytes is preferred for Cr(VI) exposure; requires careful method optimization to avoid interferences for Cd [41]. |

| Halogenated Flame Retardants (HFRs) | Parent compounds (e.g., HBCDD) | Serum | GC-MS with ECNI or LC-MS/MS | Technique selection depends on the specific compound; GC-MS/MS is an emerging alternative [41]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: LC-MS/MS Analysis of Urinary Parabens and Bisphenols

The following protocol, adapted from NHANES and cohort study methodologies, outlines a standard procedure for the simultaneous quantification of parabens and bisphenols in urine [25] [24].

1. Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect spot urine samples in pre-cleaned containers without preservatives.

- Freeze samples at -20°C or lower immediately after collection and maintain this temperature until analysis to prevent degradation.

- Thaw samples overnight at 4°C and vortex thoroughly to ensure homogeneity.

2. Hydrolysis and Deconjugation:

- Pipette 1 mL of urine into a centrifuge tube.

- Add an appropriate volume of an enzyme solution containing β-glucuronidase/sulfatase (e.g., from Helix pomatia) to hydrolyze the conjugated metabolites back to their free forms.

- Incubate the mixture for several hours (e.g., 12-16 hours) at 37°C in a shaking water bath.

3. Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE):

- Dilute the hydrolyzed urine sample with a buffer (e.g., ammonium acetate, pH 6.5).

- Condition a reversed-phase C18 SPE cartridge sequentially with methanol and the dilution buffer.

- Load the diluted urine sample onto the cartridge, wash with a water/methanol mixture, and elute the target analytes with pure methanol.

- Evaporate the eluent to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen and reconstitute the residue in a mobile phase compatible with LC-MS/MS (e.g., water/methanol).

4. Instrumental Analysis via LC-MS/MS:

- Chromatography: Separate the analytes using a reversed-phase UHPLC system. A C18 column (e.g., 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.8 µm) is typically used. The mobile phase consists of (A) water and (B) methanol, both with 0.1% formic acid, using a gradient elution from 20% B to 95% B over 10-15 minutes.

- Mass Spectrometry: Utilize an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in negative ion mode. Detection is performed via multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). Example transitions include:

- Methylparaben: 151 → 136

- Bisphenol A: 227 → 212

- Quantification is achieved using isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., ¹³C-BPA, D4-Methylparaben) for each analyte to correct for matrix effects and recovery losses.

5. Quality Assurance/Quality Control (QA/QC):

- Include calibration standards, reagent blanks, and quality control materials (pooled urine spiked at low and high concentrations) in each analytical batch.

- Report results with creatinine correction to account for urinary dilution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful HBM analysis relies on a suite of high-purity reagents and specialized materials. The following table details the essential components of a researcher's toolkit for quantifying EDCs.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HBM of EDCs

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Quantification and correction for matrix effects. | Examples: ¹³C-Bisphenol A, D4-Monoethyl phthalate (D4-MEP). Crucial for achieving high accuracy in mass spectrometry [43] [44]. |

| β-Glucuronidase/Sulfatase Enzyme | Enzymatic deconjugation of phase-II metabolites in urine. | Releases the free, aglycone form of the analyte for measurement, essential for assessing total body burden [25]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Sample clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes. | Reversed-phase C18 or mixed-mode sorbents are commonly used to remove interfering compounds from the biological matrix [25]. |

| Chromatography Columns | Separation of analytes prior to mass spectrometric detection. | UHPLC columns with sub-2µm particle size (e.g., C18, 100 mm x 2.1 mm) provide high-resolution separation, reducing ion suppression [43]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation and quality control. | Used to establish accuracy and traceability of measurements; available from organizations like NIST [40]. |

HBM Workflow: From Sample to Public Awareness

The journey of HBM from a biological sample to a catalyst for public awareness and policy involves a meticulously structured workflow. The following diagram illustrates the key stages of this process.

Human Biomonitoring stands as an indispensable scientific tool, providing the most direct and definitive evidence of human exposure to bisphenols, phthalates, parabens, and other EDCs. The sophistication of analytical techniques like LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS enables the precise quantification of these chemicals at trace levels, generating the robust data required for credible health risk assessments. This technical capability is the foundation upon which public awareness is built and validated. By translating abstract concerns about "chemicals in the environment" into concrete, measurable data on "chemicals in our bodies," HBM empowers individuals, informs public discourse, and provides policymakers with the evidence needed to enact protective regulations. As analytical methods continue to advance towards greater sensitivity and efficiency, HBM will undoubtedly play an even more critical role in bridging the gap between scientific evidence and public health action, ensuring that awareness leads to tangible reductions in exposure and risk.

Within the context of public awareness research on endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and parabens, the ability to accurately measure public perceptions is paramount [28] [12]. These environmental contaminants, prevalent in consumer products and linked to adverse health outcomes including reproductive issues and metabolic disorders, represent a significant public health concern [12] [45]. Social surveys employing well-designed questionnaires and Likert scales serve as critical methodological tools for quantifying public understanding, risk perception, and perceived harmfulness of these chemicals [36]. This technical guide provides researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework for developing, implementing, and analyzing surveys aimed at capturing reliable data on chemical risk perceptions, with specific application to EDC research.

Likert Scale Fundamentals and Design Considerations

A Likert scale is a psychometric measurement tool used to quantify attitudes, opinions, or perceptions through a series of structured response options [46] [47]. Typically, respondents indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with a specific statement along a symmetric continuum, often with five or seven points [48]. The fundamental strength of Likert scales lies in their ability to transform subjective qualitative perceptions into quantifiable ordinal data suitable for statistical analysis [47].

Scale Structure and Response Options

The design of response options significantly impacts data quality and respondent experience. Key considerations include the number of scale points and the framing of responses [46] [48].

- Number of Scale Points: While 5-point and 7-point scales are most common, the optimal choice depends on the desired balance between granularity and respondent burden [48]. Odd-numbered scales typically include a neutral midpoint, while even-numbered scales force respondents toward a positive or negative direction [46].

- Bipolar vs. Unipolar Scales: Bipolar scales measure two opposing attributes along a single continuum (e.g., "Extremely harmful" to "Not at all harmful"), whereas unipolar scales measure the intensity of a single attribute (e.g., "Not at all harmful" to "Extremely harmful") [46]. For perceived harmfulness, a unipolar approach often provides more precise measurement.

Table 1: Common Likert Response Formats for Measuring Perceived Harmfulness

| Scale Type | Number of Points | Response Options | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | 5 or 7 | Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree | Assessing agreement with specific risk statements |

| Perceived Harm | 5 | Not at all harmful, Slightly harmful, Moderately harmful, Very harmful, Extremely harmful | Direct measurement of harm perceptions |

| Frequency | 5 | Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always | Measuring frequency of risk-avoidance behaviors |

| Importance | 5 | Not at all important to Extremely important | Gauging importance of regulatory actions |

Crafting Effective Likert Items