Advancing Reproductive Health: Behavioral Strategies for Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical Avoidance and Intervention

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence and methodological approaches for understanding and promoting reproductive health behaviors aimed at reducing exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs).

Advancing Reproductive Health: Behavioral Strategies for Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical Avoidance and Intervention

Abstract

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence and methodological approaches for understanding and promoting reproductive health behaviors aimed at reducing exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the mechanistic foundations of EDC effects on reproductive systems, evaluates validated assessment tools and behavioral intervention strategies, addresses implementation challenges and knowledge gaps, and examines comparative effectiveness of different intervention models. The review emphasizes the critical importance of evidence-based behavioral interventions alongside pharmaceutical and regulatory approaches for protecting reproductive health across the lifespan.

Understanding the Threat: EDC Mechanisms and Reproductive Health Consequences

Environmental endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a broad class of synthetic and naturally occurring compounds that can interfere with the normal function of the endocrine system, posing a significant threat to reproductive health globally [1] [2]. These substances infiltrate our environment through industrial, agricultural, and consumer sources, leading to widespread human exposure through diet, inhalation, and dermal contact [1] [3]. The molecular mechanisms by which EDCs exert their effects are complex and multifaceted, involving direct receptor interactions, epigenetic modifications, and induction of cellular stress pathways [1]. Understanding these fundamental mechanisms is crucial for developing evidence-based avoidance behaviors and intervention strategies to mitigate the risks EDCs pose to reproductive health. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on the molecular underpinnings of endocrine disruption, with a specific focus on implications for reproductive health and the theoretical foundations for avoidance behaviors.

Core Molecular Mechanisms of Action

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals employ diverse strategies to interfere with hormonal signaling. The primary molecular mechanisms can be categorized into four key areas, each with distinct pathways and consequences.

Nuclear Receptor Interference

The most characterized mechanism of EDCs involves direct interaction with nuclear hormone receptors, particularly estrogen receptors (ERs) and androgen receptors (ARs). These interactions can either mimic or block the actions of endogenous hormones.

Receptor Agonism/Antagonism: EDCs such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates structurally mimic natural hormones like 17β-estradiol, enabling them to bind to estrogen receptors with high affinity [1]. This binding can initiate transcription of estrogen-responsive genes, leading to inappropriate activation of estrogenic pathways. Conversely, compounds like vinclozolin act as androgen receptor antagonists, blocking normal androgen signaling and impairing masculinization and reproductive development [1].

Receptor Cross-Talk: Beyond direct binding, EDCs can modulate receptor activity through cross-talk with other signaling pathways. For instance, certain EDCs activate membrane-associated estrogen receptors (e.g., GPER), which trigger rapid non-genomic signaling cascades that ultimately influence nuclear transcription [1] [4]. This cross-talk creates complex signaling networks that extend the disruptive potential of EDCs beyond classical receptor pathways.

Non-Receptor Mediated Pathways

EDCs also disrupt endocrine function through mechanisms that do not involve direct receptor binding, primarily by inducing oxidative stress and disrupting metabolic pathways.

Oxidative Stress Induction: Heavy metals like cadmium and lead, as well as various organic pollutants, promote excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [1]. This oxidative stress damages cellular macromolecules including lipids, proteins, and DNA, particularly affecting sperm membranes and viability. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles, for instance, induce ROS production with an ED50 of 150 mg/kg, resulting in significant sperm membrane damage [1].

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Many EDCs specifically target mitochondrial function, impairing energy production and further exacerbating oxidative stress. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) penetrate the blood-testis barrier and trigger inflammatory cascades that substantially impair sperm motility by compromising mitochondrial ATP production [1].

Epigenetic Modifications

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of EDC exposure is their ability to induce heritable changes through epigenetic mechanisms, potentially affecting multiple generations.

DNA Methylation Alterations: EDCs including BPA, phthalates, and persistent organic pollutants can alter DNA methylation patterns at critical gene regulatory regions [1]. These changes can silence or activate genes involved in hormonal signaling, gametogenesis, and reproductive development.

Transgenerational Inheritance: Animal studies provide compelling evidence that EDC-induced epigenetic modifications can be transmitted to subsequent generations without additional exposure [1]. For example, ancestral exposure to vinclozolin has been shown to impair fertility across multiple generations through stable changes in sperm DNA methylation patterns [1].

Table 1: Classification of Major Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Their Primary Molecular Targets

| Chemical Category | Representative EDCs | Primary Molecular Targets | Exposure Routes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals | Cadmium, Lead, Arsenic | Blood-testis barrier, Antioxidant systems, DNA integrity | Contaminated food/water, Occupational exposure |

| Synthetic Organics | BPA, Phthalates (DEHP) | Estrogen receptors, Androgen receptors, Epigenetic regulators | Food packaging, Personal care products, Plastics |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants | PCBs, Dioxins, PBDEs | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor, Thyroid hormone receptors, Androgen synthesis enzymes | Animal fats, Contaminated fish, Environmental persistence |

| Fluorinated Pesticides | Various fluorinated compounds | Estrogen receptors, Multiple nuclear receptors | Agricultural runoff, Food residues, Environmental contamination |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Advancements in research methodologies have been crucial for elucidating the complex mechanisms of endocrine disruption and identifying novel EDCs.

Traditional Toxicology Approaches

Traditional toxicological methods have established foundational knowledge about EDC effects through standardized testing protocols.

In Vivo Animal Studies: Rodent models have been extensively used to assess the reproductive effects of EDCs across the lifespan. These studies measure endpoints such as sperm quality, hormone levels, organ weights, and morphological changes [1]. For example, studies exposing rats to a common mixture of EDCs during gestation or infancy found altered food preferences and weight gain in adulthood, accompanied by physical changes in brain regions controlling food intake and reward [5].

Cell-Based Assays: Established cell lines provide controlled systems for investigating specific molecular pathways. These assays can examine receptor binding affinity, gene expression changes, and cellular responses to EDC exposure [4]. Cell models are particularly valuable for high-throughput screening of potential endocrine activity and for elucidating specific mechanisms of action at the cellular level [4].

Advanced Mechanistic Approaches

Emerging technologies are transforming EDC research by enabling more comprehensive and human-relevant assessments.

Transcriptomics and Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs): A novel approach combines RNA-sequencing of zebrafish embryos with structured AOP networks to predict endocrine-disrupting potential without traditional animal testing [6]. This method identifies gene expression changes following chemical exposure and links these molecular initiating events to potential adverse outcomes through established biological pathways [6]. The automated, data-driven approach helps structure and interpret complex transcriptomic data, connecting early molecular changes to potential health effects.

Epigenetic Mapping: Advanced sequencing technologies enable genome-wide mapping of epigenetic modifications induced by EDCs. These approaches can identify specific regions of the genome susceptible to EDC-induced methylation changes and correlate these alterations with functional outcomes [1].

Table 2: Key Experimental Models for Studying Endocrine Disruption Mechanisms

| Model System | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo (Rodent) | Developmental exposure studies, Transgenerational effects, Integrated physiological responses | Captures complex systemic interactions, Whole-organism context | Species differences, Time and cost intensive, Ethical considerations |

| Cell Lines | High-throughput screening, Specific pathway analysis, Receptor binding studies | Controlled environment, Mechanistic studies, Human cells possible | Limited tissue complexity, Does not capture systemic effects |

| Zebrafish Embryos | Rapid screening, Developmental toxicity, Transcriptomic analysis | Transparent embryos, High fecundity, Genetic tractability | Evolutionary distance from mammals, Different metabolic pathways |

| Computational/AOP Networks | Data integration, Predictive toxicology, Pathway analysis | Reduces animal use, Integrates diverse data types, Framework for prediction | Limited by existing knowledge, Validation challenges |

Research Reagent Solutions

Cutting-edge research on endocrine disruption mechanisms relies on specialized reagents and tools that enable precise investigation of molecular pathways.

Molecular Profiling Tools

RNA-Sequencing Kits: Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis kits are essential for identifying gene expression changes in response to EDC exposure. These tools were used in the zebrafish model study to analyze which genes were affected by cadmium and PCB-126 exposure and predict the biological processes involved [6].

Epigenetic Modification Kits: Commercial kits for assessing DNA methylation patterns (e.g., bisulfite sequencing kits) and histone modifications enable researchers to map EDC-induced epigenetic changes across the genome, providing insights into potential transgenerational effects [1].

Specialized Assay Systems

Receptor Binding Assays: Fluorescence-based and radio-labeled ligand binding assays allow quantitative assessment of EDC interactions with nuclear receptors (ERα, ERβ, AR, TR). These assays provide critical data on binding affinity and potency for prioritization and risk assessment [4].

Oxidative Stress Detection Kits: Commercial kits for measuring reactive oxygen species, antioxidant capacity, and oxidative damage products (e.g., lipid peroxidation, 8-oxo-dG) are crucial for quantifying EDC-induced cellular stress [1].

Visualization of Molecular Mechanisms

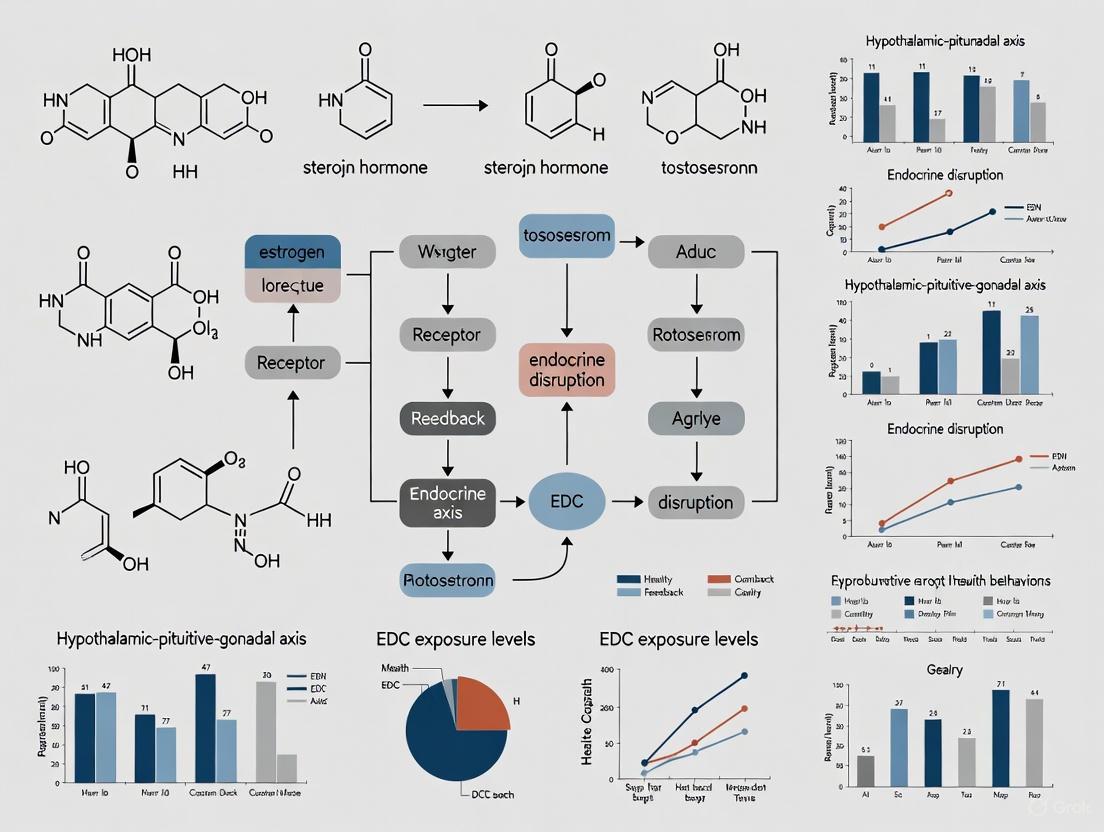

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows for studying endocrine disruption mechanisms.

Molecular Interference Pathways

Experimental Workflow for EDC Identification

The molecular mechanisms underlying endocrine disruption involve complex interactions at multiple biological levels, from direct receptor binding to epigenetic reprogramming. Understanding these mechanisms provides the scientific foundation for developing targeted avoidance behaviors and intervention strategies to protect reproductive health. Advanced research methods, particularly those integrating omics technologies with adverse outcome pathway frameworks, offer promising approaches for identifying EDCs and elucidating their mechanisms without exclusive reliance on animal testing. As research continues to uncover the subtle yet profound ways in which EDCs alter hormonal signaling, this knowledge must inform both public health recommendations and regulatory policies to reduce exposure and mitigate the risks to current and future generations.

The concept of "critical windows of vulnerability" posits that specific periods during development exhibit heightened sensitivity to environmental insults, with consequences that can persist across the lifespan. Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), nutritional deficiencies, and other stressors during these precise developmental phases can disrupt organogenesis, programming, and maturation processes, leading to long-term functional deficits and increased disease risk. Understanding the temporal specificity of these exposures is paramount for developing targeted intervention strategies, particularly within the framework of reproductive health behaviors and EDC avoidance theory. This review synthesizes evidence on critical windows from fetal development through adulthood, emphasizing quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and implications for public health and clinical practice.

Theoretical Framework: Critical Windows and Developmental Origins of Health and Disease

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis provides a foundational framework for understanding how environmental factors during sensitive developmental periods influence long-term health trajectories. Critical windows represent specific temporal phases when developing systems exhibit maximal susceptibility to perturbation due to rapid cell division, differentiation, and morphogenetic events. Exposure to stressors during these windows can induce permanent alterations in tissue structure and function through epigenetic reprogramming, changes in stem cell populations, and disruption of hormonal signaling.

Within reproductive health behavior research, EDC avoidance theory seeks to identify modifiable behaviors that reduce exposure during these critically vulnerable periods. The theory posits that knowledge of critical windows, combined with understanding of exposure routes and sources, can motivate and guide protective behaviors among vulnerable populations, particularly during preconception and gestational periods.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Critical Windows Across the Lifespan

| Developmental Stage | Critical Windows | Key Vulnerable Systems | Primary Environmental Stressors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal Development | Weeks 1-13 (Organogenesis) | Neural tube, cardiac system, foundational structures | Nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iron), EDCs, temperature extremes |

| Weeks 10-37 (System-specific maturation) | Auditory system, metabolic programming, growth | EDCs, temperature extremes, nutritional deficits | |

| Childhood | Early postnatal period | Brain maturation, immune system | EDCs, infectious agents, psychosocial stress |

| Adolescence | Pubertal transition | Reproductive system, brain remodeling | EDCs, psychosocial stress, substance use |

| Adulthood | Preconception period | Germ cell quality (sperm/oocyte) | EDCs, nutritional status, oxidative stress |

Critical Windows in Fetal Development: Experimental Evidence

Nutritional Insufficiencies: The Case of Iron Deficiency

Iron deficiency during pregnancy represents a well-characterized model for understanding critical windows of vulnerability. Animal models with precise dietary manipulation have demonstrated that the timing of iron restriction produces differential effects on fetal development.

Experimental Protocol: In a seminal rat model study, researchers established four distinct dietary-feeding protocols to induce iron deficiency during specific gestational stages [7]. Dams were provided a customized iron-deficient diet either prior to conception or during specific trimesters. Functional outcomes in offspring were assessed using Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) measurements at postnatal days 40-45, when the auditory system is fully developed.

Key Findings: Maternal iron restriction initiated prior to conception and during the first trimester was associated with profound neural impairment in offspring, evidenced by significantly increased ABR interpeak latencies across all frequencies tested (0.25±0.18 ms to 0.49±0.034 ms, p<0.0001) [7]. Iron restriction later in pregnancy produced less severe effects. Importantly, these impairments occurred even in the absence of severe maternal anemia, indicating that iron deficiency without anemia during critical windows can disrupt fetal CNS development.

Table 2: Effects of Timing of Iron Deficiency on Fetal Development in a Rat Model

| Timing of Iron Restriction | Embryonic Iron Concentration | Fetal Weight (E19) | ABR Interpeak Latency | Neural Impairment Severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-conception + 1st trimester | 44% of control at E15 | ~40% lighter at E15 | Significantly increased | Profound |

| Later gestation only | Progressive decrease from E15 | Moderately reduced | Moderately increased | Moderate |

| Adequate iron throughout | Normal developmental increase | Normal developmental pattern | Normal range | Minimal |

Temperature Extremes During Gestation

Ambient temperature exposure during pregnancy represents another environmental factor with time-dependent effects on fetal development.

Experimental Protocol: A retrospective cohort study of 1,129,572 singleton births in Wuhan, China (2011-2022) linked daily ambient temperature data at 1-km² resolution to maternal residential coordinates [8]. Researchers used extended distributed lag non-linear models combined with logistic regression to examine associations between weekly temperature exposure and small vulnerable newborn (SVN) outcomes, including preterm birth (PTB), small for gestational age (SGA), and low birth weight (LBW).

Key Findings: The research identified distinct critical windows for heat and cold exposure with remarkable weekly resolution. Heat exposure during weeks 10-23 and 34-37 increased PTB risk, peaking at week 37 (OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.09-1.13) [8]. Cold exposure during weeks 1-13 and 22-33 increased PTB risk, most notably at week 28 (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.07-1.10). For LBW, heat exposure during weeks 9-24 and 37-42 increased risks, strongest at week 42 (OR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.16-1.21). The exposure-response relationship exhibited U-shaped, J-shaped, or L-shaped patterns depending on the gestational week, demonstrating substantial heterogeneity in temperature sensitivity across development.

Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical Exposures

EDCs present a particularly insidious threat during critical developmental windows due to their ability to interfere with hormonal signaling at extremely low concentrations.

Experimental Protocol: The Reducing Exposures to Endocrine Disruptors (REED) study protocol outlines a randomized controlled trial testing a self-directed online interactive curriculum with live counseling sessions and individualized support to reduce EDC exposure among reproductive-aged men and women [9]. Participants provide urine samples before and after the intervention for biomonitoring of phthalates, bisphenols, parabens, and oxybenzone.

Key Findings: While longitudinal outcome data are forthcoming, baseline observations confirm the ubiquitous exposure to EDCs in reproductive-aged populations. Previous intervention studies demonstrate that personalized feedback on exposure levels combined with educational resources can significantly reduce urinary concentrations of certain phthalates (monobutyl phthalate decreased with p<0.001) and increase avoidance behaviors [9].

Methodological Approaches for Identifying Critical Windows

Animal Models for Precise Temporal Manipulation

Animal models remain indispensable for identifying critical windows due to the ability to precisely control the timing and intensity of exposures. The rat model of iron deficiency exemplifies this approach, with carefully controlled dietary regimens administered during specific gestational windows [7]. Key methodological considerations include:

- Dietary Control: Customized iron-deficient diets administered during precise gestational days

- Functional Assessment: ABR measurements as a sensitive functional readout of neural development

- Tissue Analysis: Atomic absorption spectroscopy for quantifying iron concentrations in embryonic tissues

Large-Scale Epidemiological Studies with Temporal Resolution

Large retrospective cohort studies with detailed exposure data enable the identification of critical windows in human populations. The temperature exposure study exemplifies this approach with several methodological strengths [8]:

- High-Resolution Exposure Data: Daily ambient temperature data at 1-km² resolution linked to maternal residential coordinates

- Weekly Analytical Framework: Extended distributed lag non-linear models examining associations with weekly resolution

- Population Scale: Over 1 million births providing substantial statistical power for detecting associations

Intervention Studies for Modifiable Behaviors

Randomized controlled trials of behavioral interventions provide evidence for reducing exposures during critical windows. The REED study incorporates several innovative methodological elements [9]:

- Personalized Report-Back: Individualized exposure reports with urinary levels, health effect information, and personalized recommendations

- Interactive Curriculum: Self-directed online modules with live counseling sessions

- Biomonitoring: Pre- and post-intervention urine testing to quantify exposure reduction

Diagram 1: Critical Windows of Vulnerability Across Gestation. Different developmental stages exhibit specific sensitivity to environmental stressors, with the timing of exposure determining potential adverse outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Studying Critical Windows

| Reagent/Methodology | Primary Application | Key Function in Vulnerability Research | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy | Quantification of elemental concentrations | Measures tissue iron levels in embryonic and postnatal tissues | Determining embryonic iron concentration in rat models [7] |

| Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) | Functional assessment of neural development | Non-invasive measurement of nerve conduction velocity in auditory system | Detecting neural impairment in iron-deficient offspring [7] |

| Distortion-Product Otoacoustic Emissions (DPOAE) | Assessment of peripheral auditory function | Exclusion of hair cell dysfunction as confounder for ABR measurements | Confirming central rather than peripheral neural deficits [7] |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry | Biomonitoring of EDCs | Quantification of urinary phthalate, phenol, and paraben metabolites | Measuring intervention effectiveness in EDC reduction studies [9] |

| Distributed Lag Non-Linear Models | Statistical analysis of time-varying exposures | Identification of critical exposure windows with high temporal resolution | Determining weekly temperature susceptibility windows [8] |

Implications for Public Health and Clinical Practice

Understanding critical windows of vulnerability has profound implications for developing targeted interventions and public health recommendations. The evidence suggests that:

- Preconception and Early Pregnancy Interventions may be most effective for preventing certain developmental impairments, as demonstrated by the profound effects of first-trimester iron deficiency [7].

- Time-Specific Recommendations for avoiding temperature extremes could potentially reduce adverse birth outcomes, with precise weekly guidance possible based on identified critical windows [8].

- Personalized EDC Reduction Strategies that provide specific, actionable recommendations based on individual exposure profiles can effectively reduce body burden of these chemicals during vulnerable life stages [9].

Educational interventions targeting reproductive-aged populations have shown promise in increasing knowledge and promoting avoidance behaviors. Studies demonstrate that greater knowledge of specific EDCs like phthalates and parabens significantly predicts chemical avoidance in personal care products [10]. However, significant knowledge gaps remain, with chemicals like triclosan and perchloroethylene being poorly recognized even among educated populations [10].

Diagram 2: Framework for Targeted Interventions Based on Critical Windows. Effective public health interventions require identification of exposure timing, development of targeted strategies, and rigorous evaluation of outcomes.

Critical windows of vulnerability represent discrete temporal phases during which developing systems exhibit heightened sensitivity to environmental perturbations. Evidence from studies of nutritional deficiencies, temperature extremes, and EDC exposures demonstrates that the timing of insult is often as important as the dose in determining long-term outcomes. The fetal period, particularly during organogenesis and system-specific maturation, presents multiple critical windows with potential lifelong consequences.

Future research directions should include: (1) refined temporal mapping of critical windows using high-resolution exposure assessment and modeling approaches; (2) elucidation of molecular mechanisms underlying developmental vulnerability, including epigenetic reprogramming and stem cell susceptibility; and (3) development of targeted interventions based on identified critical windows to maximize protective effects during the most vulnerable developmental periods. Integration of this knowledge into clinical practice and public health policy offers the promise of more effective strategies for protecting developmental health across the lifespan.

Reproductive health encompasses physical, mental, and social well-being in all matters relating to the reproductive system, not merely the absence of disease or disorders [11]. In recent decades, a growing body of evidence has identified concerning trends in reproductive health outcomes, including rising rates of infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), early puberty, and menopause acceleration. These conditions represent significant challenges to individual well-being, public health systems, and global demographic patterns.

This technical guide examines the complex interplay between environmental exposures, particularly to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), and their role in the pathogenesis of these reproductive health outcomes. Framed within the context of reproductive health behaviors and EDC avoidance theory, this review synthesizes current scientific evidence, provides detailed methodological approaches for studying these relationships, and offers a toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals working in this rapidly evolving field. The comprehensive analysis presented here aims to bridge laboratory research, clinical practice, and public health policy by providing mechanistic insights, standardized protocols, and evidence-based intervention strategies.

Reproductive Health Outcomes: Prevalence and Pathophysiology

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS represents one of the most common endocrine disorders affecting women of reproductive age, with an estimated global prevalence of 6-13% [12]. Despite its prevalence, up to 70% of affected women remain undiagnosed worldwide, creating a significant public health gap [12]. The condition is characterized by three cardinal features: oligo- or anovulation, clinical or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovarian morphology [13]. PCOS remains a leading cause of anovulatory infertility and represents the most common endocrine disturbance in reproductive-aged women [13] [12].

The pathophysiology of PCOS manifests across the female lifespan, beginning with early markers in infancy and continuing through menopause. Daughters of women with PCOS show increased anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels in infancy, early childhood, and prepubertally, suggesting an increased follicle complement and mild metabolic abnormalities compared with controls [14]. During adolescence, PCOS often presents with premature pubarche (development of pubic/axillary hair before age 8 years) and a wider age range at menarche [13] [14]. The transition through reproductive years is marked by a gradual decrease in the severity of PCOS features, though hyperandrogenism and menstrual irregularities often persist [14]. In menopause, women with a history of PCOS continue to manifest cardiovascular risk factors, though longitudinal studies on long-term outcomes remain limited [14].

Table 1: Diagnostic Features and Prevalence of PCOS Across the Lifespan

| Life Stage | Key Features | Prevalence/Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infancy/Childhood | Increased AMH levels (proxy for follicle number); mild metabolic abnormalities | Studied in daughters of women with PCOS; strong heritability component | [14] |

| Puberty/Adolescence | Premature pubarche; wider age range at menarche; hyperandrogenism; irregular menses | Diagnosis challenging due to overlap with normal puberty; hyperandrogenemia most reliable diagnostic criterion | [13] [14] |

| Reproductive Years | Oligo/anovulation; hyperandrogenism; polycystic ovarian morphology; insulin resistance | 6-13% of reproductive-aged women; leading cause of anovulatory infertility | [13] [12] |

| Menopause | Higher Ferriman-Gallwey scores; increased cardiovascular risk factors; possible later menopause | Limited longitudinal data; metabolic features may persist | [14] |

Infertility and Menstrual Dysfunction

Infertility represents a significant consequence of multiple reproductive health disorders, with PCOS being a predominant cause. Approximately 75-85% of women with PCOS experience irregular menstrual cycles due to ovulatory dysfunction [13]. The mechanisms of anovulation in PCOS involve disordered follicle development from the earliest phases through to the antral stages, with persistence and assumed arrest of larger antral follicles [13]. These "arrested" follicles comprise those that have already undergone terminal differentiation together with healthy follicles that have stopped growing due to suboptimal FSH stimulation [13].

The impact of PCOS on fertility varies with age. While pregnancy rates are similar amongst younger women with and without PCOS, older women with PCOS have been found to have lower numbers of deliveries overall, lower average number of children, and higher rates of infertility [13]. Pregnancy in women with PCOS is associated with higher risks of complications including miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, low birth weight, and gestational diabetes mellitus, particularly in those with obesity [13].

Early Puberty and Menopause Acceleration

Emerging evidence suggests that environmental factors, including EDC exposure, may influence the timing of pubertal onset and reproductive senescence. Early life exposures to EDCs have been associated with premature pubarche, which may be an early sign of PCOS and later reproductive dysfunction [13] [14]. The relationship between birth weight and pubertal timing appears complex, with both low and high birth weight associated with higher AMH levels in infancy, suggesting alterations in follicular development that may influence reproductive lifespan [14].

Women with PCOS appear to have a later age of menopause, though longitudinal studies are lacking and the experience of women with PCOS in peri/postmenopause remains poorly studied [13]. The benefits and risks associated with menopausal hormone replacement therapy in women with PCOS represent a significant knowledge gap in current literature.

EDCs and Reproductive Health

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are synthetic compounds that interfere with the normal function of the endocrine system through multiple mechanisms. Some EDCs directly bind to hormone receptors, such as estrogen, androgen, and thyroid hormone receptors, either mimicking or blocking their functions, thereby disrupting the body's normal physiological processes [11]. The reproductive system is particularly vulnerable to EDC exposure, as many EDCs exert estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects that can lead to reduced sperm count, smaller male reproductive organs, abnormal reproductive behaviors, and decreased fertility rates [11].

EDCs enter the body through various exposure routes, including food, air, and skin absorption, making them nearly unavoidable in daily life [11]. Women are disproportionately exposed to EDCs through personal care and household products (PCHPs), encountering an estimated 168 different chemicals daily [3]. This heightened exposure is particularly concerning during vulnerable life stages such as preconception, pregnancy, and lactation, when EDC exposures can have transgenerational effects.

Table 2: Common Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals, Sources, and Reproductive Health Impacts

| EDC | Common Sources | Primary Functions | Reproductive Health Impacts | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phthalates | Scented PCHPs; hair care products; lotions; cosmetics; household cleaners | Plasticizer, preservative | Estrogen mimicking/hormonal imbalances; reproductive effects/impaired fertility; antiandrogenic effects | [3] [9] |

| Parabens | Shampoos & conditioners; lotions; cosmetics; antiperspirants; household cleaners | Preservative | Carcinogenic potential; estrogen mimicking/hormonal imbalances; reproductive effects/impaired fertility | [3] |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) and analogs | Plastic packaging of PCHP; antiperspirants; detergents; conditioners; lotions | Plasticizer | Fetal disruptions/placental abnormalities; reproductive effects; mammary carcinogen | [3] [9] |

| Lead | Cosmetics (lipsticks, eyeliner); household cleaners | Color enhancer | Infertility; menstrual disorders; disturbances to fetal development; possibly carcinogenic | [3] |

| Triclosan | Toothpaste/mouth wash; body washes; dish soaps; bathroom cleaners | Antimicrobial | Miscarriage; impaired fertility; fetal developmental effects | [3] |

| Perchloroethylene (PERC) | Spot removers; floor cleaners; furniture cleaners; dry cleaning | Solvent | Probable carcinogen; reproductive effects/impaired fertility | [3] |

Mechanistic Insights: EDC Disruption of Reproductive Pathways

EDCs interfere with reproductive physiology through multiple interconnected mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates key pathways through which EDCs disrupt normal reproductive function:

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of EDC Disruption in Reproductive Health. EDCs interfere with multiple physiological pathways including the HPO axis, hormone receptor signaling, follicular development, and metabolic function, leading to diverse reproductive pathologies.

Methodological Approaches: Assessing EDC Exposure and Reproductive Outcomes

EDC Exposure Assessment Methodologies

Accurate assessment of EDC exposure represents a critical component of research on reproductive health outcomes. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for EDC exposure assessment and intervention evaluation:

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Workflow for EDC Exposure and Reproductive Health Research. This methodology integrates exposure assessment, health outcome measurement, intervention components, and statistical analysis to evaluate EDC-reproductive health relationships.

Validated Survey Instruments for EDC Exposure and Reproductive Health Behaviors

Several validated survey instruments have been developed to assess EDC-related knowledge, risk perceptions, and avoidance behaviors. Kim et al. (2025) developed and validated a 19-item survey assessing reproductive health behaviors to reduce EDC exposure through four factors: health behaviors through food, health behaviors through breathing, health behaviors through skin, and health promotion behaviors [11]. This instrument utilizes a 5-point Likert scale and has demonstrated acceptable reliability (Cronbach's alpha = 0.80) [11].

The Health Belief Model (HBM) has been successfully applied to understand and predict EDC avoidance behaviors. A Toronto-based study of 200 women in preconception and conception periods utilized a researcher-designed questionnaire based on the HBM to assess knowledge, health risk perceptions, beliefs, and avoidance behaviors regarding EDCs in personal care and household products [3]. The questionnaire demonstrated acceptable reliability in preliminary analyses and identified that greater knowledge of specific EDCs (lead, parabens, bisphenol A, and phthalates) significantly predicted chemical avoidance in PCHPs [3].

Biomarker Assessment in EDC Research

Biomonitoring represents the gold standard for assessing internal EDC exposure. Phthalates, parabens, bisphenols, and other EDCs can be measured in urine, blood, saliva, and other biological matrices. The Million Marker program has pioneered mail-in urine testing kits for EDC biomonitoring, making exposure assessment more accessible for research and clinical applications [9]. These methods are particularly valuable given the short half-lives of many EDCs (6 hours to 3 days), which reflects recent exposure and enables researchers to track changes in exposure following interventions [9].

Recent advances have integrated clinical biomarker assessment with EDC intervention studies. The Reducing Exposures to Endocrine Disruptors (REED) study protocol includes testing for clinical biomarkers (via at-home Siphox tests) to evaluate whether EDC reduction interventions lead to improvements in health parameters such as metabolic markers, hormone levels, and inflammatory markers [9]. This approach addresses a critical gap in connecting EDC exposure reduction with measurable health improvements.

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EDC and Reproductive Health Research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Application/Function | Technical Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomonitoring | Urine collection kits; LC-MS/MS systems; ELISA kits; SPE cartridges | Quantification of EDCs and metabolites in biological samples | Consider short half-lives; measure multiple analogs; account for specific gravity | [9] |

| Clinical Biomarkers | Hormone panels (testosterone, estrogen, LH, FSH, AMH); metabolic panels (glucose, insulin, lipids); inflammatory markers (CRP, cytokines) | Assessment of reproductive and metabolic health status | AMH correlates with antral follicle count; consider menstrual cycle timing | [13] [9] |

| Survey Instruments | Validated EDC knowledge scales; Health Belief Model questionnaires; Readiness to Change assessments; Product use inventories | Measure knowledge, perceptions, behaviors related to EDC exposure | Ensure cultural adaptation; validate in specific populations; use consistent scaling | [3] [11] |

| Intervention Materials | Educational curricula on EDC sources; Product replacement kits; Counseling protocols; Digital health platforms | Implement and test EDC exposure reduction strategies | Personalized approaches show greater efficacy; combine with biomonitoring feedback | [9] [15] |

| Data Analysis | Statistical software (R, SPSS); Structural equation modeling; Mixed-effects models; Mediation analysis packages | Analyze complex exposure-outcome relationships; model behavioral change | Account for multiple comparisons; adjust for key covariates; consider non-monotonic dose responses | [3] [11] |

EDC Avoidance Theory and Intervention Strategies

Theoretical Frameworks for Behavior Change

The Health Belief Model has demonstrated utility in understanding and promoting EDC avoidance behaviors. According to this framework, women who perceive a heightened risk of health impacts from EDC exposure and understand the health implications become more concerned about chemical-based products [3]. If they believe that choosing EDC-free products can lower their risk, they are more likely to adjust their purchasing behavior accordingly [3]. Research has confirmed that higher risk perceptions of parabens and phthalates predict greater avoidance behaviors [3].

Educational interventions that increase EDC-related health literacy (EHL) have shown promising results in promoting behavior change. A previous intervention study found that after report-back of personal EDC exposure results, participants demonstrated increased EHL behaviors and women showed increased readiness to change their exposure behaviors [9]. Participants reported subsequently using non-toxic personal products (50%), using non-toxic household products (44%), dining out less (20%), eating less packaged food (32%), using less plastic (40%), and reading product labels more (48%) [9].

Effective Intervention Components

Evidence-based EDC reduction interventions typically incorporate several key components. Accessible web-based educational resources, targeted replacement of known toxic products, and personalization of the intervention through meetings and support groups represent the most promising strategies for reducing EDC concentrations [15]. The REED study protocol incorporates an online interactive curriculum with live counseling sessions and individualized support modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program [9].

Product replacement represents a particularly effective intervention strategy. Research has demonstrated that providing participants with alternatives to high-EDC products leads to significant reductions in urinary biomarkers of exposure. For example, replacing conventional personal care products with certified low-EDC alternatives for as little as three days can reduce urinary concentrations of certain phthalates, parabens, and phenols by 27-45% [15].

Global Family Planning and Reproductive Health Context

Reproductive health outcomes, including infertility and PCOS, must be understood within the broader context of global family planning needs. Current data indicate that 928 million women in low- and middle-income countries want to avoid pregnancy, yet 214 million are not using modern contraception [16]. Among those with unmet needs, 78 million women intend to use or would be open to using contraception in the future, representing a strategic target for family planning interventions [16].

Meeting the global need for sexual and reproductive health services requires significant investment. An estimated $104 billion annually is needed to meet all sexual and reproductive health needs in low- and middle-income countries, with $14 billion needed annually specifically to close the contraceptive gap alone [16]. These investments yield significant returns, with every additional $1 spent on contraceptive services saving $2.48 in maternal, newborn, and abortion care costs [16].

Family planning interventions also demonstrate important economic benefits beyond health outcomes. In Kenya and Nigeria, women's use of contraception led to a 10-12% increase in doing paid work the following year and a nearly 15% increase in control over use of wages [16]. In Burkina Faso, Kenya, and Niger, longer duration of contraceptive use was associated with women experiencing more years of paid employment with control over use of their earnings [16].

The intricate relationships between EDC exposure, reproductive health behaviors, and adverse reproductive outcomes represent a critical area of scientific inquiry with significant implications for clinical practice and public health policy. The evidence synthesized in this review demonstrates that EDCs contribute to the pathogenesis of infertility, PCOS, early puberty, and potentially menopause acceleration through multiple mechanistic pathways. Framed within the context of EDC avoidance theory, this guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with comprehensive methodological approaches, validated assessment tools, and evidence-based intervention strategies to advance this field.

Significant knowledge gaps remain that warrant further investigation. Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies tracking EDC exposures and reproductive outcomes across the lifespan, intervention trials testing the efficacy of EDC reduction strategies on clinical endpoints, and mechanistic studies elucidating the precise pathways through which EDCs disrupt reproductive function. Additionally, research should explore potential ethnic variations in EDC metabolism and susceptibility, develop more sensitive biomarkers of effect, and validate brief assessment tools for clinical identification of high-risk individuals.

As the field advances, collaboration across disciplines—including environmental health, reproductive endocrinology, epidemiology, and behavioral science—will be essential to translate scientific evidence into effective clinical and public health interventions. By integrating EDC exposure reduction strategies into reproductive healthcare and family planning services, we may mitigate the burden of adverse reproductive outcomes and improve health across generations.

Transgenerational Effects and Epigenetic Modifications from EDC Exposure

Environmental endocrine disruptors (EDCs) represent a class of widespread chemical contaminants that interfere with normal hormonal signaling, with growing evidence indicating they can induce heritable epigenetic changes affecting multiple generations [17]. The transgenerational inheritance of EDC-induced phenotypes represents a paradigm shift in understanding environmental impacts on health, moving beyond direct toxic effects to encompass germline epigenetic reprogramming that can manifest as disease susceptibility in subsequent generations. While epidemiological associations between EDC exposure and reproductive dysfunction are well-established, the mechanistic underpinnings of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance remain an area of intense investigation [17] [18].

This technical guide synthesizes current evidence on EDC-mediated transgenerational epigenetic effects, focusing on molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and implications for reproductive health across generations. The content is framed within the broader context of reproductive health behaviors and EDC avoidance theory, providing researchers with the conceptual frameworks and technical tools necessary to advance this critically important field.

Molecular Mechanisms of EDC-Induced Epigenetic Modifications

EDCs disrupt normal epigenetic programming through multiple interconnected pathways that can become permanently encoded in the germline, leading to transgenerational inheritance of reproductive abnormalities [17]. The primary molecular mechanisms include:

DNA Methylation Alterations

DNA methylation patterns, particularly at imprinted gene loci and metastable epialleles, are highly vulnerable to disruption by EDC exposure during critical developmental windows. The establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation marks during embryogenesis and germ cell development represent key periods of epigenetic vulnerability [17]. EDCs including bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and persistent organic pollutants have been demonstrated to induce hypermethylation or hypomethylation at specific genomic regions that control the expression of genes critical for reproductive development and function. These altered methylation patterns can be transmitted through the germline and maintained across generations, even in the absence of continued exposure [17].

Histone Modifications

EDC exposure can profoundly alter the post-translational modification landscape of histones, including methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation changes that regulate chromatin accessibility and gene expression. These histone modifications serve as epigenetic marks that can be propagated during cell division and potentially transmitted across generations. Specific EDCs have been shown to modulate the activity and expression of histone-modifying enzymes such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone methyltransferases, leading to lasting changes in chromatin states that influence gene expression programs in reproductive tissues [17].

Non-Coding RNA Regulation

Small non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs and piwi-interacting RNAs, have emerged as important mediators of EDC-induced transgenerational epigenetic effects. These regulatory RNAs can be altered in the germline following EDC exposure and contribute to the transmission of epigenetic information across generations. The dysregulation of non-coding RNA networks can result in persistent changes in gene expression that manifest as reproductive pathologies in subsequent generations, even without direct exposure [17].

Table 1: Primary Epigenetic Mechanisms of EDC Action

| Mechanism | Key EDCs Involved | Molecular Consequences | Transgenerational Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Alterations | BPA, Phthalates, Vinclozolin | Hypermethylation of hormone response genes; Hypomethylation of repetitive elements | Confirmed in animal models across multiple generations [17] |

| Histone Modifications | Persistent Organic Pollutants, Heavy Metals | Altered histone acetylation/methylation patterns at promoters of steroidogenic genes | Demonstrated in animal studies; human evidence emerging |

| Non-Coding RNA Regulation | Plasticizers, Pesticides | Dysregulation of miRNA expression profiles in sperm and germ cells | Experimental evidence in animal models |

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected molecular pathways through which EDC exposure leads to transgenerational epigenetic effects:

Experimental Evidence for Transgenerational Inheritance

Animal Model Studies

Compelling evidence for EDC-induced transgenerational epigenetic effects comes from well-controlled animal studies that have demonstrated the inheritance of reproductive abnormalities across multiple generations. These studies typically expose pregnant females during critical periods of germline epigenetic reprogramming in the developing fetus, then track phenotypic and epigenetic changes in subsequent generations (F1-F3) without additional exposure [17]. The F3 generation represents the first truly transgenerational cohort when exposure occurs during gestation, as the F1 generation fetus and F2 generation germline are directly exposed, while the F3 generation is the first without direct exposure [17].

Research has shown that EDCs including vinclozolin, methoxychlor, BPA, and phthalates can induce transgenerational inheritance of disease states, particularly affecting male reproductive function. Documented effects include reduced sperm motility and concentration, increased sperm apoptosis, and morphological abnormalities in reproductive tissues [17]. These phenotypic changes are associated with transcriptional alterations in the testis and specific epigenetic modifications in sperm, including differential DNA methylation regions and changes in non-coding RNA expression [17].

Human Evidence and Epidemiological Studies

While animal studies provide compelling mechanistic evidence for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, human evidence remains limited due to the extended timeframes required for multigenerational studies and practical challenges of maintaining long-term cohorts across decades [17]. However, some epidemiological studies have suggested transgenerational effects through analysis of generational exposures and disease incidence patterns.

The available human evidence primarily comes from retrospective cohort studies and analysis of historical exposure events, which suggest potential transgenerational effects of EDCs on reproductive health. These studies face significant methodological challenges, including accurate exposure assessment across generations, controlling for confounding factors, and the long latency between exposure and phenotypic manifestation [17].

Table 2: Transgenerational Effects of Select EDCs in Animal Models

| EDC Class | Specific Compound | Exposure Window | F1 Generation Effects | F3 Generation Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungicide | Vinclozolin | Gestational days 8-15 | 20% reduction in sperm motility; 30% increase in apoptosis | 50% reduction in sperm motility; 70% of males infertile |

| Plasticizer | BPA | Gestational days 10-18 | 15% decrease in sperm concentration; altered sexual behavior | 25% decrease in sperm concentration; social behavior deficits |

| Phthalate | DEHP | Gestational days 10- birth | 18% reduction in testosterone; testicular abnormalities | 30% reduction in sperm count; 40% increase in pubertal abnormalities |

| Insecticide | Methoxychlor | Gestational days 8-15 | 25% reduction in sperm viability; kidney disease | 60% disease incidence; 90% of males have spermatogenic defects |

Methodological Approaches for Transgenerational EDC Research

Experimental Design Considerations

Robust investigation of transgenerational epigenetic effects requires carefully controlled experimental designs that account for the unique challenges of multigenerational studies. Key considerations include:

Exposure Timing: The developmental stage during EDC exposure is critical, as windows of germline epigenetic reprogramming represent periods of heightened vulnerability. In mammalian models, gestational exposure during primordial germ cell development and gonadal sex determination is particularly effective at inducing transgenerational effects [17].

Dose Selection: Environmental relevance of exposure doses should be prioritized, with consideration of non-monotonic dose responses that are characteristic of many EDCs. Studies should include multiple dose levels when possible, including human-relevant exposure levels [17].

Generational Analysis: Proper experimental design must distinguish between direct multigenerational effects (F0-F2) and true transgenerational inheritance (F3 and beyond) when exposure occurs during gestation [17].

Epigenetic Analysis Techniques

Comprehensive assessment of EDC-induced epigenetic changes requires multimodal approaches that capture different layers of epigenetic regulation:

DNA Methylation Analysis: Genome-wide approaches include whole-genome bisulfite sequencing for comprehensive methylation mapping and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing for cost-effective assessment of CpG-rich regions. Locus-specific methods such as pyrosequencing provide high-precision quantification of methylation at candidate regions [17].

Histone Modification Profiling: Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) enables genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites. Antibody specificity and chromatin quality are critical factors for reproducible results [17].

Non-Coding RNA Analysis: Small RNA sequencing provides comprehensive profiling of miRNA and other small non-coding RNAs, with special considerations for the unique biogenesis and stability of different RNA classes [17].

The following diagram outlines a standardized experimental workflow for transgenerational EDC research:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transgenerational EDC Research

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDC Reference Standards | Bisphenol A (BPA), Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), Vinclozolin | Controlled exposure studies; analytical standard for exposure verification | Purity >99%; stable isotope-labeled versions for exposure quantification |

| Epigenetic Analysis Kits | EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit, EpiQuik HDAC Activity Assay, Magna ChIP Kit | DNA methylation analysis; histone modification assessment; chromatin immunoprecipitation | Batch-to-batch consistency; minimal DNA degradation during processing |

| Antibodies for Histone Modifications | H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac | ChIP-seq; immunohistochemistry; western blotting | Specificity validation for species; lot-to-lot consistency |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | TruSeq DNA Methylation, Small RNA Library Prep, ChIP-seq Library Prep | Genome-wide epigenetic profiling | Compatibility with sequencing platform; optimization for input material |

| Germ Cell Isolation Reagents | Collagenase IV, Trypsin-EDTA, Percoll gradients, Fluorescent-activated cell sorting buffers | Isolation of specific germ cell populations | Maintenance of cell viability; preservation of epigenetic marks |

| Quality Control Assays | Bioanalyzer/Tapestation, Qubit Fluorometric Quantitation, Bisulfite Conversion Efficiency | Assessment of nucleic acid quality and quantity | Accurate quantification of low-input samples; verification of complete bisulfite conversion |

Implications for Reproductive Health and EDC Avoidance Theory

The transgenerational epigenetic effects of EDCs have profound implications for reproductive health behaviors and public policy. Understanding that current exposures may impact multiple future generations strengthens the imperative for preventative approaches to EDC exposure [17] [9]. This evidence supports the development of comprehensive EDC avoidance strategies targeting susceptible populations, particularly during critical developmental windows such as pregnancy and early childhood [9].

Recent intervention studies demonstrate that personalized exposure reduction programs can significantly decrease body burdens of EDCs, supporting the potential for breaking cycles of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [9]. These interventions combine biomonitoring approaches with educational components to empower individuals to reduce exposures through behavioral modifications, demonstrating significant reductions in EDC metabolites following targeted interventions [9].

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, critical knowledge gaps remain in understanding EDC-induced transgenerational epigenetic effects. Key research priorities include:

Mixture Toxicology: Most studies examine individual EDCs, while real-world exposure involves complex mixtures. Research on interactive effects of EDC mixtures on epigenetic programming is needed [17].

Human Translation: Bridging the gap between compelling animal model data and human evidence requires innovative epidemiological approaches and potential analysis of human germline epigenetic changes [17].

Mechanistic Resolution: Deeper understanding of how specific epigenetic marks are established, maintained, and transmitted across generations will clarify the fundamental principles of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [17].

Intervention Strategies: Development of evidence-based interventions to prevent or reverse EDC-induced epigenetic changes represents a critical frontier for protecting reproductive health across generations [9].

The emerging evidence for transgenerational epigenetic effects of EDCs underscores the urgency of addressing environmental chemical exposures as a matter of intergenerational justice, with implications for regulatory policy, clinical practice, and individual lifestyle choices aimed at preserving reproductive health for future generations.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a significant and growing concern in public health, particularly regarding reproductive outcomes. This whitepaper provides a technical overview of five major EDC classes—bisphenols, phthalates, parabens, pesticides, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—focusing on their mechanisms of action, reproductive toxicity, and methodologies for their study. Mounting epidemiological and experimental evidence links exposure to these compounds with adverse reproductive health effects in both males and females, including reduced sperm quality, altered steroidogenesis, diminished ovarian reserve, and increased risk of conditions like endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome. Understanding the specific pathways through which these chemicals exert their effects is crucial for developing targeted therapeutic interventions and informing public health policies aimed at exposure reduction. This document serves as a technical primer for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of environmental toxicology and reproductive medicine.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are exogenous substances or mixtures that alter function(s) of the endocrine system and consequently cause adverse health effects in an intact organism, or its progeny, or (sub)populations [19]. The global decline in human fertility rates has occurred concurrently with increased production and environmental release of synthetic chemicals, suggesting a potential link that has prompted intensive research efforts [19]. EDCs can interfere with hormonal action through multiple mechanisms, including mimicking natural hormones, blocking hormone receptors, and altering the production, transport, metabolism, or elimination of natural hormones [19]. The reproductive system is particularly vulnerable to EDC exposure during critical developmental windows, such as fetal development, puberty, and reproductive adulthood, with effects that may manifest immediately or decades later [19].

Bisphenols

Bisphenol-A (BPA) is a high-production-volume chemical primarily used in the manufacture of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins. These materials are found in numerous consumer goods, including food and beverage containers, dental materials, and thermal receipt paper [20] [21]. BPA monomers can leach from these products, especially when heated or damaged, leading to widespread human exposure through dietary intake, dermal absorption, and inhalation [21].

Mechanisms of Reproductive Toxicity

BPA exerts its endocrine-disrupting effects through both genomic and non-genomic pathways. Structurally similar to estradiol, BPA can bind to estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), acting as a xenoestrogen and mimicking the effects of natural estrogens [20] [21]. Additionally, BPA can interfere with other nuclear receptors, including androgen and thyroid hormone receptors [21]. Non-genomic effects include interference with cellular signaling pathways and epigenetic modifications that can alter gene expression patterns critical for reproductive development and function [21].

Bisphenol-A (BPA) Signaling Interference Pathways

Experimental Approaches for BPA Research

In vitro models utilizing cell lines derived from reproductive tissues (e.g., granulosa cells, Sertoli cells) are employed to study the direct effects of BPA on cellular function. Typical experimental protocols involve exposing these cells to varying concentrations of BPA (ranging from nM to μM) across different time courses, followed by assessment of gene expression, hormone production, and cell viability [22]. For endocrine disruption screening, reporter gene assays in ER-transfected cell lines quantify the estrogenic activity of BPA. In vivo studies often utilize perinatal exposure paradigms in rodent models to examine the long-term reproductive effects of developmental BPA exposure. These studies administer BPA via drinking water or diet at environmentally relevant doses (2-50 μg/kg/day) and assess outcomes including pubertal onset, ovarian follicle counts, sperm parameters, and hormone levels throughout the lifespan [20] [21].

Key Research Reagents for BPA Studies

| Research Reagent | Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| ERα/ERβ Reporter Cell Lines | In vitro screening | Detect estrogenic activity via luciferase expression |

| Anti-17β-HSD1 Antibody | Enzyme activity assays | Quantify expression of estrogen-activating enzyme |

| BPA Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Sample purification | Selective extraction of BPA from biological matrices |

| LC-MS/MS Standards (deuterated BPA) | Analytical quantification | Internal standard for precise biomonitoring |

| DNA Methylation Kits | Epigenetic analysis | Assess BPA-induced changes in methylation patterns |

Phthalates

Phthalates are a class of chemicals primarily used as plasticizers to increase the flexibility and durability of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics. Common phthalates include diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), diethyl phthalate (DEP), di-isononyl phthalate (DiNP), and di-iso-decyl phthalate (DiDP) [23]. These compounds are not covalently bound to the plastic matrix and can readily leach into the environment. Human exposure occurs primarily through ingestion of contaminated food and water, inhalation of indoor air, and dermal absorption from personal care products and medical devices [23]. Phthalates are rapidly metabolized in the human body, with monoester metabolites and secondary oxidative metabolites excreted in urine and feces, making these metabolites useful biomarkers for exposure assessment [23].

Mechanisms of Reproductive Toxicity

Phthalates exert anti-androgenic effects through multiple mechanisms, primarily by reducing testosterone synthesis in Leydig cells through suppression of gene expression encoding steroidogenic enzymes [23]. They also induce oxidative stress in germ cells and disrupt the blood-testis barrier by degrading intercellular junctions between Sertoli cells [23] [24]. In females, phthalates can interfere with folliculogenesis and steroid hormone production, potentially leading to reduced ovarian reserve and hormonal imbalances [19]. Some phthalates have also been shown to affect gene expression through epigenetic modifications, including altered DNA methylation status of imprinted genes involved in reproductive function [23].

Phthalate Metabolic Pathways and Toxicity Mechanisms

Experimental Approaches for Phthalate Research

A standard methodology for assessing phthalate exposure involves measuring urinary metabolites using liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). This biomonitoring approach typically includes enzymatic deconjugation of phase II metabolites, solid-phase extraction, and quantification using isotope-labeled internal standards [23]. For mechanistic studies, in vitro models utilize primary cultures of Leydig cells or human granulosa cell lines (e.g., COV434) exposed to phthalate metabolites like mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) to examine effects on steroid hormone production and gene expression [23] [22]. Animal studies often employ developmental exposure protocols where pregnant rodents receive phthalates in their diet (50-1000 mg/kg/day) during critical windows of reproductive tract development, with offspring assessed for anomalies in reproductive organ development, sperm parameters, and fertility in adulthood [23].

Key Research Reagents for Phthalate Studies

| Research Reagent | Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Phthalate Metabolites | LC-MS/MS analysis | Internal standards for quantitative accuracy |

| Anti-StAR Antibody | Steroidogenesis assays | Detect expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein |

| Oxidative Stress Assay Kits | Cellular stress measurement | Quantify ROS production in germ cells |

| Tight Junction Protein Antibodies | Histological analysis | Visualize blood-testis barrier integrity |

| CYP17A1 Inhibitors | Enzyme activity studies | Compare with phthalate effects on steroidogenesis |

Parabens

Parabens are alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid widely used as preservatives in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and processed foods due to their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, low cost, and chemical stability [22]. Common parabens include methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben, often used in combination to enhance preservative efficacy. Human exposure occurs primarily through dermal absorption from personal care products and to a lesser extent via dietary intake [22]. Although parabens are rapidly metabolized by esterases in the liver and skin to p-hydroxybenzoic acid and excreted in urine as conjugates, continuous exposure from multiple sources leads to persistent body burdens [22].

Mechanisms of Reproductive Toxicity

Parabens can disrupt endocrine function through multiple mechanisms. They exhibit weak estrogen receptor agonist activity and can inhibit estrogen-synthesizing (17β-HSD1) and estrogen-inactivating (17β-HSD2) enzymes in a structure-dependent manner [22]. Longer-chain parabens (hexyl- and heptylparaben) more potently inhibit 17β-HSD1, which converts estrone to the more biologically active estradiol, thereby potentially reducing local estrogen concentrations [22]. Conversely, shorter-chain parabens like ethylparaben inhibit 17β-HSD2, which inactivates estradiol, potentially increasing local estrogen concentrations [22]. This differential inhibition of estrogen-regulating enzymes can disrupt the delicate balance of estrogen signaling in reproductive tissues.

Experimental Approaches for Paraben Research

In vitro screening for paraben activity typically involves enzyme inhibition assays using recombinant 17β-HSD1 and 17β-HSD2. The standard protocol incubates the enzyme with its substrate (estrone for 17β-HSD1, estradiol for 17β-HSD2) and cofactor (NADPH for 17β-HSD1, NAD+ for 17β-HSD2) in the presence of varying concentrations of paraben test compounds [22]. Reaction products are quantified using HPLC or LC-MS/MS, and IC₅₀ values are calculated from dose-response curves. Cellular models include human granulosa COV434 cells endogenously expressing 17β-HSD1 to confirm enzyme inhibition in intact cells [22]. Molecular docking studies using crystal structures of target enzymes (e.g., PDB code: 1FDT) help predict binding modes and structure-activity relationships [22].

Key Research Reagents for Paraben Studies

| Research Reagent | Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant 17β-HSD1/2 | Enzyme inhibition assays | Target proteins for screening paraben effects |

| NADP+/NADPH Cofactors | Enzyme activity measurements | Essential cofactors for HSD enzyme reactions |

| Estrone/Estradiol Standards | HPLC/LC-MS quantification | Reference standards for steroid quantification |

| Paraben Analytical Standards | Exposure assessment | Calibration standards for bio-monitoring |

| Molecular Docking Software | Structure-activity studies | Predict paraben-enzyme binding interactions |

Pesticides

Pyrethroids constitute an important class of extensively used insecticides identified as EDCs. Permethrin is one of the most commonly used pyrethroids and exists in multiple stereoisomeric forms due to two chiral centers in its structure [25]. These compounds are widely applied in agricultural and household settings, leading to human exposure through dietary residues, inhalation, and dermal contact. Despite their relatively low environmental persistence compared to organochlorine pesticides, pyrethroids are ubiquitous in the environment due to high-volume applications, and they have been detected in human biomonitoring studies [25].

Mechanisms of Reproductive Toxicity

Pyrethroids can interfere with reproductive function through multiple pathways. They have been shown to act as androgen receptor antagonists, potentially disrupting androgen signaling critical for male reproductive development and function [25]. Structural binding studies indicate that permethrin stereoisomers can compete with native ligands for binding to the androgen receptor ligand-binding domain, with potential to interfere with AR function [25]. Pyrethroid exposure has also been associated with altered serum levels of gonadotropins and testosterone in animal studies, suggesting disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis [25]. Additionally, some pyrethroids have demonstrated estrogenic activity in screening assays, indicating potential for mixed endocrine-disrupting effects.

Experimental Approaches for Pesticide Research

Computational approaches include induced fit docking simulations to study the structural binding characteristics of pesticide stereoisomers with nuclear receptors like the androgen receptor (PDB code: 2AM9) [25]. The methodology involves protein preparation (addition of hydrogens, optimization of hydrogen bond networks, energy minimization), ligand preparation (generation of stereoisomers), and induced fit docking that allows flexibility in both receptor and ligand [25]. In vitro validation utilizes reporter gene assays in AR-transfected cells to confirm antagonistic activity. Animal studies typically administer pesticides to rodents during critical developmental periods (e.g., gestational days 14-18) and assess reproductive outcomes in adulthood, including anogenital distance, sperm parameters, and reproductive organ weights [25].

Key Research Reagents for Pesticide Studies

| Research Reagent | Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| AR Reporter Cell Lines | Receptor activity screening | Detect AR antagonistic activity |

| Crystallized AR Protein | Structural studies | Reference structure for docking studies |

| Deuterated Pesticide Standards | Analytical quantification | Internal standards for exposure assessment |

| Stereoisomerically Pure Pesticides | Mechanistic studies | Test enantiomer-specific effects |

| Testosterone ELISA Kits | Hormone measurement | Quantify endocrine effects in vivo |

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of synthetic chemicals characterized by strongly fluorinated alkyl chains that confer exceptional stability and persistence in the environment. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) are two well-studied representatives of this class [24]. These compounds have been widely used in industrial and consumer products, including non-stick cookware, food packaging, stain-resistant fabrics, and fire-fighting foams. Due to their environmental persistence and bioaccumulation potential, PFAS are detected globally in human populations, with elimination half-lives of approximately 3.5 years for PFOA and 5.4 years for PFOS in humans [24].

Mechanisms of Reproductive Toxicity

PFAS compounds disrupt reproductive function through multiple interconnected mechanisms. In males, they induce apoptosis and autophagy in spermatogenic cells, disrupt Leydig cell function, cause oxidative stress in sperm, degrade intercellular junctions between Sertoli cells, and alter hypothalamic metabolome [24]. In females, PFAS exposure damages oocytes through oxidative stress, inhibits corpus luteum function, disrupts steroid hormone synthesis, impairs gap junction intercellular communication in follicles, and inhibits placental function [24]. These mechanisms collectively contribute to the observed adverse reproductive outcomes in both epidemiological studies and experimental models.

PFAS Reproductive Toxicity Mechanisms

Experimental Approaches for PFAS Research

Epidemiological studies typically employ cross-sectional or longitudinal designs measuring serum PFAS concentrations in relation to reproductive endpoints such as semen quality, reproductive hormone levels, and time-to-pregnancy [24]. Laboratory-based approaches include in vitro models using primary granulosa cells or placental cell lines to examine the effects of PFAS on steroidogenesis and cell viability, with typical exposure concentrations ranging from 0.1-100 μM [24]. Animal studies often use oral administration of PFAS (1-20 mg/kg/day) during critical developmental windows to assess long-term reproductive effects. Mechanistic studies focus on specific pathways, such as measuring oxidative stress markers, apoptosis assays, and gap junction communication in relevant cell types [24].

Key Research Reagents for PFAS Studies

| Research Reagent | Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| PFAS Analytical Standards | Exposure assessment | Quantification in environmental/biological samples |

| Oxidative Stress Assay Kits | Mechanism studies | Measure ROS production in gametes |

| Gap Junction Communication Dyes | Functional assays | Assess cell-to-cell communication in follicles |

| Apoptosis/Caspase Assay Kits | Cell death analysis | Quantify germ cell apoptosis |

| Steroid Hormone Antibodies | Immunoassays | Detect alterations in hormone production |

Comparative Analysis of EDC Classes

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key EDC Parameters

| EDC Class | Representative Compounds | Primary Exposure Routes | Half-Life in Humans | Key Reproductive Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenols | BPA | Dietary, dermal, inhalation | Hours | Sperm alterations, testicular atrophy, hormonal imbalances, reduced ovarian reserve |

| Phthalates | DEHP, DBP, DiNP | Dietary, inhalation, dermal | ~12 hours | Reduced testosterone, sperm DNA damage, ovarian dysfunction, folliculogenesis disruption |

| Parabens | Methylparaben, Ethylparaben, Butylparaben | Dermal, dietary | Hours (rapid metabolism) | Estrogenic effects, inhibition of 17β-HSD enzymes, potential breast cancer links |

| Pesticides | Permethrin, Pyrethroids | Dietary, dermal, inhalation | Days | AR antagonism, altered gonadotropin levels, sperm quality reduction |

| PFAS | PFOA, PFOS | Dietary, drinking water | 3.5-5.4 years | Sperm count reduction, testicular hormone disruption, ovarian damage, placental dysfunction |

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for EDC Research

| EDC Class | Typical In Vitro Concentrations | Typical In Vivo Doses (Rodent) | Key Molecular Targets | Standard Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenols | 1 nM - 100 μM | 2-50 μg/kg/day (low dose) | ERα/ERβ, steroidogenic enzymes | Reporter assays, LC-MS, histological analysis |