A Comprehensive Protocol for Developing and Validating Reproductive Health Behavior Questionnaires

This article provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for developing and validating robust reproductive health behavior questionnaires.

A Comprehensive Protocol for Developing and Validating Reproductive Health Behavior Questionnaires

Abstract

This article provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for developing and validating robust reproductive health behavior questionnaires. Aimed at researchers and clinical professionals, it synthesizes current methodologies from foundational qualitative research and item generation to advanced psychometric validation and intervention optimization. The protocol covers essential stages including defining conceptual frameworks, conducting cognitive interviews, applying rigorous scale development techniques like exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, and utilizing modern optimization frameworks such as the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST). It also addresses troubleshooting common pitfalls and emphasizes the critical role of cross-cultural validation to ensure tools are reliable, valid, and applicable for diverse populations in both research and clinical settings.

Laying the Groundwork: Conceptual Frameworks and Initial Item Generation

Defining the Construct and Target Population

The initial phase of developing a reproductive health behavior questionnaire is foundational, setting the trajectory for all subsequent research and instrument validation. This stage involves the precise definition of the construct to be measured and the explicit specification of the target population from which data will be collected. A meticulously executed definition process ensures the questionnaire's content validity, guaranteeing that the instrument comprehensively captures the full spectrum of the reproductive health behaviors it intends to measure [1]. Within the broader thesis on questionnaire development protocol, this phase dictates the appropriateness of all future psychometric evaluations and the ultimate utility of the tool in research or clinical settings.

Framing the construct within a recognized theoretical model of health behavior is paramount. Furthermore, the definition must be culturally contextualized, reflecting the specific beliefs, norms, and healthcare access realities of the intended population, as a construct valid in one cultural setting may not hold in another [2]. This document outlines detailed application notes and experimental protocols for systematically defining the construct and target population for a reproductive health behavior questionnaire.

Conceptual Foundations and Literature Review

The Importance of a Clear Construct

In psychometrics, a "construct" refers to the abstract concept, theme, or behavior that the questionnaire aims to measure. A well-defined construct provides a clear framework for item generation and ensures that all questions are relevant to the research objective. For reproductive health, this is particularly critical due to the multifaceted nature of the field, which encompasses physical, mental, and social well-being [2] [3].

A shift from a deficit-based perspective to a well-being-focused framework is emerging in the field. Traditional metrics often focus on adverse outcomes like unintended pregnancy or disease rates. In contrast, a construct centered on Sexual and Reproductive Well-Being (SRWB) aims to capture whether people are living the sexual and reproductive lives they wish to, aligning with reproductive justice and human rights frameworks [3]. This positive, person-centered approach should be considered when defining the construct for a new questionnaire.

Core Components of a Reproductive Health Behavior Construct

The table below summarizes potential domains and their behavioral indicators relevant to defining a reproductive health behavior construct, synthesized from existing literature.

Table 1: Potential Domains and Behavioral Indicators for a Reproductive Health Construct

| Domain | Description | Example Behavioral Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Preventive Health-Seeking | Behaviors related to seeking information and services to maintain reproductive health. | Frequency of health check-ups; online health information-seeking [4]; contraceptive counseling uptake. |

| Risk Reduction & Management | Actions taken to minimize the risk of adverse reproductive health outcomes. | Consistent contraceptive use; STI testing behaviors; smoking or alcohol cessation during pregnancy [2]. |

| Fertility and Parenthood Behaviors | Behaviors related to achieving or avoiding pregnancy, and parenting. | Pregnancy planning activities; fertility treatment-seeking; prenatal care adherence [5]. |

| Partner and Sexual Communication | Interpersonal behaviors concerning sexual and reproductive health. | Communication with partners about sexual history, contraception, or reproductive desires [2]. |

| Health Literacy and Self-Care | Daily practices and knowledge application for self-management of reproductive health. | Adherence to medical regimens; engagement in healthy diet/exercise [2]; correct use of health products. |

Operational Definitions and Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Construct Elucidation via Qualitative Exploration

1. Objective: To explore and define the nuanced dimensions of the reproductive health behavior construct from the perspective of the target population.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Audio recording equipment

- Semi-structured interview guide

- Transcribed interview transcripts

- Qualitative data analysis software (e.g., NVivo, MAXQDA)

3. Experimental Workflow: This protocol employs a qualitative study design, typically using contractual or conventional content analysis, to generate items from the ground up [2] [5].

4. Data Analysis: Data are analyzed inductively to identify meaning units, which are condensed into codes, grouped into subcategories, and finally organized into main themes or dimensions representing the construct [5]. The trustworthiness of data is ensured through credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability [5].

Protocol 2: Systematic Literature Review for Construct Dimension Identification

1. Objective: To systematically identify established and theoretically-grounded dimensions of reproductive health behavior to inform and complement the qualitative findings.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Access to scientific databases (e.g., PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science)

- Reference management software (e.g., EndNote, Zotero)

- Data extraction forms

3. Experimental Workflow: This protocol involves a systematic search of national and international literature to map the existing knowledge and tools related to the construct [6].

4. Data Analysis: Findings from the literature review are integrated with the results from the qualitative phase (Protocol 1). The goal is to create a comprehensive and comparative list of items and dimensions, ensuring the preliminary instrument is both culturally relevant (from qualitative data) and scientifically grounded (from literature) [2] [6].

Protocol 3: Operational Definition of the Target Population

1. Objective: To establish clear and justified inclusion and exclusion criteria for the target population.

2. Key Defining Parameters: The target population must be defined with precision to ensure the instrument's validity and future generalizability. The following parameters must be specified:

- Demographics: Age range, gender, socioeconomic status, education level, and ethnicity [2] [4].

- Clinical/Reproductive Status: Specific reproductive health experiences (e.g., women with premature ovarian insufficiency [6], women shift workers [5], men in reproductive age).

- Contextual Factors: Geographical location (urban vs. rural) [4], occupation, and cultural or religious background [2].

3. Justification: The rationale for each parameter must be documented. For example, studying women shift workers specifically is justified because shift work has documented effects on menstruation, sexual relationships, and pregnancy outcomes, requiring a tailored instrument [5].

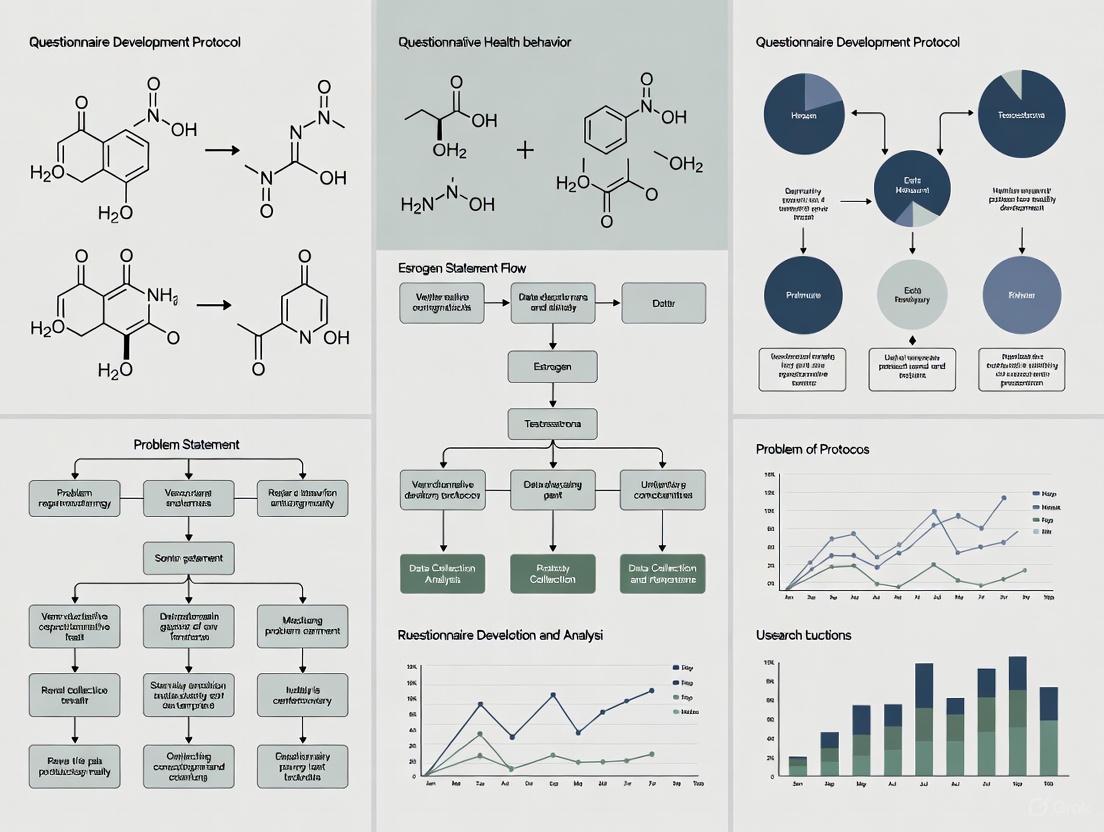

Diagram 1: Workflow for defining the construct and target population, integrating qualitative and literature-based methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Defining Construct and Population

| Research Reagent / Material | Function/Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guide | A flexible protocol to ensure key topics are covered while allowing participants to express their views freely, generating rich qualitative data [2] [5]. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo) | Facilitates the organization, coding, and thematic analysis of large volumes of textual interview data [5]. |

| Literature Search Strategy & Boolean Operators | A pre-defined, reproducible plan for searching scientific databases to ensure a comprehensive and unbiased literature review [6]. |

| Expert Panel | A group of specialists (e.g., in reproductive health, gynecology, psychology) who provide input on the relevance and comprehensiveness of the constructed dimensions, establishing content validity [5]. |

| Data Saturation Log | Documentation to track when no new information or themes are observed in qualitative data collection, signaling an adequate sample size [2]. |

Data Synthesis and Preliminary Validation

Integrating Findings into a Working Definition

The final output of this phase is a detailed, operational definition of the construct and the target population. The construct definition should clearly list the identified dimensions (e.g., motherhood, sexual relationships, general health) and their components [5]. The population definition should include finalized inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Logical Workflow for Population Stratification: The following diagram outlines the decision process for defining and stratifying the target population, which is crucial for ensuring the instrument's relevance and for planning subsequent psychometric testing.

Diagram 2: Logic flow for applying criteria to define and stratify the target population.

Output for the Next Phase

The conclusive deliverables from this stage form the direct input for the next phase of questionnaire development: Item Generation.

- A formal written Construct Definition.

- A finalized Target Population Profile with explicit criteria.

- A comprehensive list of Dimensions and Sub-Dimensions of the reproductive health behavior construct, ready to be translated into a pool of specific questionnaire items.

Conducting Formative Qualitative Research

Application Notes: The Role of Formative Qualitative Research in Questionnaire Development

Formative qualitative research is an indispensable preliminary phase in developing robust, contextually-grounded research instruments, particularly for complex fields like reproductive health. This exploratory process leverages in-depth qualitative methods to gain a nuanced understanding of the population's knowledge, attitudes, experiences, and vocabulary surrounding a health issue. These insights directly inform the content, structure, and language of subsequent quantitative survey instruments, ensuring they are comprehensive, culturally appropriate, and cognitively accessible to the target population.

Within a broader thesis on reproductive health behavior questionnaire development, formative research ensures that the final instrument accurately captures the salient beliefs, behaviors, and barriers specific to the population of interest. This methodology is especially critical when researching sensitive topics or working with diverse cultural groups, where researcher assumptions may not align with local realities. The application of these methods ensures the final questionnaire has high content validity and face validity, forming a solid foundation for psychometric testing and eventual deployment in larger-scale studies.

Experimental Protocols for Formative Qualitative Research

This section provides a detailed methodological framework for conducting formative qualitative research to inform a reproductive health behavior questionnaire.

Protocol Phase 1: Foundational Scoping

Objective: To define the core domains of inquiry and develop a preliminary understanding of the research landscape.

Detailed Methodology:

- Systematic Literature Review: Conduct a structured review of peer-reviewed literature and existing instruments to conceptualize key dimensions. As demonstrated in the development of an integrated oral, mental, and sexual reproductive health tool for adolescents, this involves defining dimensions a priori (e.g., sexual practices, health outcomes) and systematically searching databases like PubMed and ScienceDirect to identify relevant conceptualizations and measurement items [7].

- Domain Identification: Thematically analyze retrieved articles to extract information on relevant domains and subscales. The goal is to identify constructs that are statistically or conceptually associated with your core research interest [7].

- Expert Consultation: Engage a multi-disciplinary panel of experts (e.g., subject matter specialists, clinical professionals, language experts) to verify the identified domains and assess the content validity of initial concepts. The Content Validity Index (CVI) can be used quantitatively to retain items meeting a predefined threshold (e.g., I-CVI > 0.80) [8].

Protocol Phase 2: Primary Qualitative Data Collection

Objective: To gather rich, contextual data directly from the target population and key stakeholders.

Detailed Methodology: Adopt a qualitative research design guided by grounded theory principles, aiming to develop a theory or deep understanding characterized by the population's own perspectives and experiences [9]. Data collection should involve multiple activities to triangulate findings.

In-Depth Interviews (IDIs):

- Participant Selection: Purposively select participants to reflect a range of characteristics (e.g., gender, age, location, socioeconomic status) known to affect the delivery and experience of the health issue [9].

- Procedure: Conduct semi-structured interviews using a pre-tested interview guide. The guide should explore perceptions, experiences, unmet needs, and the acceptability of potential interventions or measurement approaches. For a study on digital diabetes solutions, interviews explored how digital solutions may improve care and assessed digital readiness [9]. All interviews should be audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and, if necessary, translated.

Contextual and Clinical Observations:

- Procedure: Have trained researchers shadow practitioners in their care environment for a full shift. One researcher (a trained clinician) can observe clinical competencies using a validated tool, while a second researcher observes the environment, duties, and interpersonal interactions [9]. This method provides insight into real-world practices and how the care environment influences service delivery.

- Data Recording: Use a structured observation guide to record detailed field notes. A brief semi-structured interview with the practitioner can follow the observation session to clarify observations [9].

Structured Workshops:

- Procedure: Conduct separate workshops with different stakeholder groups (e.g., practitioners, patients, family members). The aim is to collaboratively identify and prioritize advantages, challenges, and practical recommendations for the intervention or, in this context, the questionnaire's design and implementation [9].

- Facilitation: Use facilitation techniques to encourage open discussion and consensus-building on key design considerations.

Table 1: Data Collection Methods for Formative Qualitative Research

| Method | Primary Objective | Participant Profile | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-Depth Interviews (IDIs) | Explore individual experiences, perceptions, and beliefs in depth. | Patients, family members, healthcare providers. | Rich, narrative data on personal views and lived experiences. |

| Contextual Observations | Understand behaviors and practices within their natural setting. | Healthcare providers in clinical settings. | Insights into real-world workflows, environmental constraints, and unspoken practices. |

| Structured Workshops | Generate consensus and gather diverse perspectives on specific topics. | Separate groups of practitioners, patients, and family members. | Prioritized list of needs, design requirements, and potential implementation challenges. |

Protocol Phase 3: Qualitative Analysis and Item Generation

Objective: To analyze qualitative data and translate findings into a draft questionnaire.

Detailed Methodology:

- Qualitative Data Analysis: Employ a thematic analysis approach. This involves a progression from (a) identifying surface-level codes to (b) grouping similar codes to develop themes.

- Coding: Systematically code transcript excerpts and field notes to label key concepts.

- Theme Development: Examine codes for commonalities and group them into meaningful themes that answer the research questions. Qualitative analysis software (e.g., NVivo, MAXQDA) provides organizational tools for this process, though the analysis itself remains a human, interpretive task [10].

- Item Generation: Use a deductive method, or logical partitioning, to generate questionnaire items based on the defined constructs and themes identified from the literature and primary data [7].

- Source Material: Derive measurement items from validated tools and the unique themes from your qualitative data. Most items should retain their original response scales, though some can be adjusted for clarity and cultural appropriateness [7].

- Compilation: Draft a preliminary questionnaire by organizing items into logical sections (e.g., socio-demographics, knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, service utilization) [7].

Table 2: Translating Qualitative Findings into Questionnaire Items

| Qualitative Data Source | Analytic Activity | Output for Questionnaire Development |

|---|---|---|

| Interview & Workshop Transcripts | Thematic Analysis -> Initial Coding | List of emergent codes (e.g., "fear of judgment," "prioritization of convenience"). |

| Grouped Codes | Thematic Analysis -> Theme Development | Overarching themes and subthemes (e.g., "Barriers to Service Access," "Sources of Health Information"). |

| Established Themes & Constructs | Deductive Item Generation [7] | Draft survey items measuring each theme. E.g., the theme "Stigma" generates items about comfort discussing reproductive health. |

| Validated Tools & Literature | Item Compilation & Adaptation [7] | Pool of validated questions, rephrased for context, integrated with newly generated items. |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram visualizes the end-to-end protocol for using formative qualitative research in questionnaire development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Formative Qualitative Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | A predefined set of open-ended questions and prompts that ensure key topics are covered across all interviews while allowing flexibility to explore participant-specific issues in depth [9]. |

| Structured Observation Guides | A tool used during contextual observations to systematically record data on practitioner competencies, environmental factors, workflows, and interactions, ensuring consistency across different observers and settings [9]. |

| Digital Audio Recorders | Essential for capturing verbatim accounts of in-depth interviews and workshop discussions for accurate transcription and analysis. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo, MAXQDA) | Software that provides organizational tools to manage, code, and retrieve qualitative data efficiently. It aids in the coding process and visualization of relationships in the data but does not perform the analysis itself [10]. |

| Participant Information Sheets & Consent Forms | Ethically mandatory documents that clearly explain the study's purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and confidentiality measures in language accessible to the participant, ensuring informed consent is obtained. |

| Workshop Facilitation Kits | Materials including agendas, prompts, large writing surfaces (whiteboards/flipcharts), and note-taking materials to structure group discussions and effectively capture collective insights [9]. |

| Validated Cognitive Testing Protocols | A set of procedures (e.g., "think-aloud" techniques, verbal probing) used in pilot testing to evaluate if the draft questionnaire items are understood as intended by the target population. This is a critical step for refining items before validation [11]. |

Developing a Conceptual Model and Initial Domains

The development of a robust reproductive health behavior questionnaire is a critical step in addressing nuanced public health challenges. Such tools enable researchers to gather standardized, quantifiable, and comparable data on the factors that influence health behaviors and outcomes. The process is methodologically rigorous, requiring a structured approach to ensure the instrument is both valid—meaning it measures what it intends to—and reliable—meaning it produces consistent results [12]. This document outlines a detailed protocol for the initial stages of questionnaire development: establishing a conceptual model and defining the initial domains, framed within a broader research context. The guidance provided is designed for researchers, scientists, and professionals engaged in health instrument development, with a specific focus on reproductive health.

Establishing the Conceptual Foundation

A strong conceptual model provides the theoretical backbone for the questionnaire, guiding item generation and ensuring that the final instrument comprehensively addresses the constructs of interest.

Theoretical Frameworks for Behavioral Questionnaires

A well-defined theoretical framework helps in hypothesizing relationships between variables and provides a structure for organizing questionnaire domains. Several established models are applicable to reproductive health behavior research.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is a prominent framework used in reproductive health research. It posits that behavioral intention, the most immediate predictor of behavior, is influenced by three factors: Attitude (the individual's positive or negative evaluation of performing the behavior), Subjective Norms (the perceived social pressure from important others to perform or not perform the behavior), and Perceived Behavioral Control (the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior, which can also directly influence the behavior itself) [13]. This model effectively predicts intention and can be extended by integrating distal variables such as demographic factors or parental control, providing a robust structure for a conceptual model [13].

A Mixed-Methods Approach to model development, which combines qualitative and quantitative data, is highly recommended for ensuring cultural and contextual relevance. This approach involves two key phases [14] [5]:

- Qualitative Exploration: In-depth understanding of the concept is achieved through interviews and focus group discussions with the target population until data saturation is reached. For instance, one study conducted 21 interviews with women shift workers to explore the concept of reproductive health in their specific context [5]. This phase ensures the model is grounded in the lived experiences of the population.

- Item Generation: The qualitative data are analyzed (e.g., using conventional content analysis) to identify key themes and components. These components are then used to generate an initial pool of questionnaire items, often supplemented by a review of existing literature and instruments [14] [5].

Defining Initial Domains and Constructs

Domains are the broad conceptual categories that the questionnaire aims to measure. Based on the theoretical framework and qualitative research, initial domains can be defined. The table below summarizes example domains identified in relevant reproductive health questionnaire studies.

Table 1: Example Domains from Reproductive Health Questionnaire Studies

| Domain / Factor Name | Description | Source Study Population |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards reproductive health behavior | The individual's evaluation (positive or negative) of behaviors that preserve reproductive health. | Female adolescents in Iran [13] |

| Subjective Norms | The perceived social pressure from important people (e.g., parents, peers) regarding reproductive health. | Female adolescents in Iran [13] |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | The individual's perception of their ability to perform reproductive health behaviors. | Female adolescents in Iran [13] |

| Disease-related Concerns | Worries and anxieties specific to living with a health condition that affects reproductive choices. | HIV-positive women [14] |

| Sexual Relationships | Aspects related to sexual function, satisfaction, and behaviors within partnerships. | Women shift workers [5] |

| Motherhood | Issues pertaining to pregnancy, breastfeeding, and maternal health. | Women shift workers [5] |

| Menstruation | Health and regularity of the menstrual cycle. | Women shift workers [5] |

| Need for Self-Management Support | The perceived need for external help or resources to manage one's health condition. | HIV-positive women [14] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for establishing the conceptual model and initial domains, integrating both theoretical and empirical elements.

Figure 1: Workflow for developing a conceptual model and initial domains.

Experimental Protocols for Domain Validation

Once an initial item pool is generated from the conceptual model, rigorous quantitative protocols are employed to validate the proposed domain structure.

Protocol for Assessing Content Validity

Objective: To ensure the questionnaire's items are relevant, clear, and comprehensive for the intended construct and population. Materials: Preliminary item pool, panel of experts (typically 10-13), standardized rating forms. Method:

- Convene Expert Panel: Assemble a multidisciplinary panel of experts in relevant fields (e.g., reproductive health, psychology, instrument development) [13] [5].

- Quantitative Assessment:

- Content Validity Ratio (CVR): Experts rate each item on its essentiality to the construct using a 3-point scale (e.g., "essential," "useful but not essential," "not essential"). The CVR is calculated for each item, and items falling below a critical value (e.g., 0.62 for 10 experts) are removed [13] [14].

- Content Validity Index (CVI): Experts rate each item on relevance, clarity, and simplicity using a 4-point scale. The CVI is calculated, and items with a value below 0.79 should be revised or eliminated [13] [14].

- Qualitative Assessment: Experts provide open-ended feedback on grammar, wording, item allocation, and scaling, which is used to refine the items [13] [5].

- Pilot with Target Population: A small sample from the target population completes the questionnaire and is interviewed to identify any difficulties with interpretation, wording, or phrasing, establishing face validity [13] [5].

Protocol for Assessing Construct Validity via Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Objective: To empirically uncover the underlying factor structure (domains) of the questionnaire and assess how well items load onto their intended constructs. Materials: Refined item pool from content validity, statistical software (e.g., SPSS, R), a sample of participants from the target population (minimum N=300 is a common rule of thumb) [5]. Method:

- Data Collection: Administer the refined questionnaire to a sufficiently large sample.

- Data Suitability Checks: Before performing EFA, check the suitability of the data using:

- Factor Extraction: Use maximum likelihood or principal axis factoring to extract factors. The number of factors to retain can be determined by eigenvalues (>1.0) and scree plots [13] [12].

- Factor Rotation: Apply a rotation method (e.g., Varimax) to simplify the factor structure and enhance interpretability.

- Interpretation: Examine the factor loadings for each item. Loadings equal to or greater than |0.3| are typically considered acceptable for retaining an item within a factor [13] [14]. The factors are then named based on the themes of the items that load onto them.

Table 2: Key Psychometric Properties from Sample Validation Studies

| Psychometric Property | Target Value | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Content Validity | ||

| Content Validity Ratio (CVR) | > 0.62 (for 10 experts) | Mean CVR of 0.64 [13] |

| Content Validity Index (CVI) | > 0.79 per item | 104 items had CVI ≥ 0.79 [13] |

| Construct Validity | ||

| KMO Measure | > 0.8 | KMO value was acceptable [13] |

| Total Variance Explained | > 50% | Six factors accounted for 67% of variance [13] |

| Reliability | ||

| Cronbach's Alpha (Internal Consistency) | > 0.7 | Alpha = 0.92 [13]; Alpha = 0.713 [14] |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) - Test-Retest | > 0.7 (Good) | ICC = 0.86 (Total Scale) [13]; ICC = 0.952 [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Essential Materials

This section details key resources required for the experimental protocols described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Questionnaire Development and Validation

| Item / Solution | Function in Protocol | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Expert Panel | To provide qualitative and quantitative assessments of content validity. | Should include 10-13 multidisciplinary experts in relevant fields (e.g., health education, reproductive health, psychology) [13] [5]. |

| Target Population Sample | To participate in qualitative phases and pilot testing for face validity. | Participants should meet specific inclusion criteria (e.g., age, health status, experience) relevant to the research objective [14] [5]. |

| Statistical Software | To perform data management, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and reliability analysis. | Common platforms include SPSS, R (with packages like 'psych' for EFA and 'irr' for ICC), and AMOS for Confirmatory Factor Analysis [13] [15]. |

| Standardized Rating Forms | To collect structured feedback from experts during content validity assessment. | Forms should be designed for 3-point (CVR) and 4-point (CVI) Likert scales as per established guidelines [13] [14]. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Guide | To conduct in-depth qualitative exploration of the research concept. | Includes open-ended questions and probes to explore participants' experiences and perceptions until data saturation is achieved [5]. |

Generating the Preliminary Item Pool

This application note details the methodology for generating a preliminary item pool, a critical first step in developing a valid and reliable reproductive health behavior questionnaire. The process outlined below employs a sequential exploratory mixed-method design, which integrates qualitative and literature-driven approaches to ensure the item pool is both comprehensive and grounded in the lived experiences of the target population [2] [5] [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Qualitative Item Generation via Thematic Analysis

This protocol aims to generate novel items directly from the target population's narratives and experiences [2] [5].

1.1 Participant Recruitment and Sampling:

- Sampling Method: Employ purposive sampling with maximum variation to capture a wide spectrum of experiences. Key demographic and experiential characteristics for stratification include age, socioeconomic status, educational level, and clinical history (e.g., work schedule for shift workers, HIV status, or years since diagnosis) [5] [14].

- Sample Size: Recruitment continues until data saturation is achieved, typically involving 20-30 participants [5] [14].

- Inclusion Criteria: Criteria are population-specific. For a women's shift worker questionnaire, for example, participants may be required to be married, aged 18–45, with work experience exceeding two years [5].

1.2 Data Collection:

- Method: Conduct semi-structured, in-depth, individual interviews in a private setting [2] [5].

- Interview Guide: Use open-ended questions to explore perceptions and behaviors. Example prompts include:

- Data Management: Audio-record interviews and transcribe them verbatim for analysis [14].

1.3 Data Analysis:

- Method: Utilize conventional content analysis as described by Graneheim and Lundman [5].

- Process:

- Repeatedly read transcripts to achieve immersion and obtain a sense of the whole.

- Identify meaning units (words, sentences, or paragraphs related to the research aim).

- Condense meaning units into codes.

- Group similar codes into subcategories and categories based on their relationships and hidden meanings.

- Formulate themes that describe the phenomenon under study [5] [14].

- Software: Use qualitative data analysis software (e.g., MAXQDA) to manage and retrieve coded data [14].

1.4 Item Formulation:

- Convert the identified codes, subcategories, and categories into a series of preliminary questionnaire items. This represents the inductive component of the item pool [2] [14].

Protocol 2: Item Generation via Systematic Literature Review

This protocol supplements qualitative findings by identifying established concepts and existing items from prior research [5] [8].

2.1 Search Strategy:

- Databases: Search relevant scientific databases (e.g., PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science).

- Keywords: Use a combination of keywords related to the target population (e.g., "men," "HIV-positive women," "shift workers"), "reproductive health," and "questionnaire" or "instrument."

- Time Frame: Review literature from a defined period, often the past 10-20 years, to ensure contemporary relevance [8].

2.2 Data Extraction and Synthesis:

- Objective: Identify constructs, domains, and specific items from validated reproductive health assessment tools [16] [17].

- Process: Systematically extract all items from relevant questionnaires. Commonly used toolkits include the Reproductive Health Assessment Toolkit for Conflict-Affected Women (CDC) and the Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings (UNFPA/Save the Children) [16] [17].

- Outcome: This process generates a list of deductive items for potential inclusion [5].

2.3 Finalizing the Preliminary Item Pool:

- Action: Combine items derived from the qualitative analysis (Protocol 1) with those gathered from the literature review (Protocol 2).

- Refinement: Hold research team meetings to review all items, merging overlapping items and removing duplicates to form the initial preliminary item pool [14].

The following workflow summarizes this two-pronged protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for executing the protocols.

| Item Name | Function/Application in Protocol | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guide | Ensures consistent exploration of key topics across all participants while allowing flexibility to probe unique experiences [5]. | Questions: "What are the effects of shift work on reproductive health?" "What factors affect reproductive health?" [5] |

| Audio Recording Equipment | Captures participant interviews verbatim for accurate transcription and data analysis [14]. | - |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software | Aids in organizing, managing, and coding large volumes of textual data efficiently [14]. | MAXQDA software [14]. |

| Validated Reference Toolkits | Provides a foundation of pre-existing, psychometrically tested items and constructs for the literature review [16] [17]. | - Reproductive Health Assessment Toolkit for Conflict-Affected Women (CDC) [16] [17].- Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings (UNFPA/Save the Children) [16] [17]. |

| Expert Panel | Provides qualitative assessment of content validity, checking grammar, wording, item allocation, and scaling of the initial item pool [5] [13]. | Panel of 10-12 experts in fields like reproductive health, midwifery, gynecology, and occupational health [5]. |

Key Methodological Considerations

Successful execution of this phase requires careful attention to several factors:

- Theoretical Framework: In some studies, the entire process is guided by a theoretical framework (e.g., the Theory of Planned Behavior), which shapes the interview questions and literature search strategy [13].

- Data Trustworthiness (Qualitative Phase): Ensure the credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability of qualitative data through techniques like member checking, peer debriefing, and maintaining an audit trail [5].

- Pilot Testing: Conduct a pilot of the interview guide and the initial merged item pool with a small sample from the target population to assess comprehension, clarity, and relevance [8] [13].

By rigorously adhering to this mixed-method protocol, researchers can generate a robust and culturally relevant preliminary item pool, establishing a solid foundation for subsequent phases of psychometric validation, including face, content, and construct validity assessment.

Establishing Content and Face Validity

Within the rigorous process of reproductive health behavior questionnaire development, establishing content and face validity forms the foundational pillar ensuring a tool's credibility and usefulness. For researchers and drug development professionals, these initial validation stages guarantee that an instrument accurately measures the constructs it intends to measure and is perceived as relevant by its target audience. In the context of reproductive health, where topics are often sensitive and constructs complex—ranging from behaviors to reduce exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) to sexual practices and contraceptive use—methodologically sound validity establishment is not merely beneficial but essential for generating reliable data [8] [11]. This protocol provides detailed application notes for systematically establishing content and face validity, framed within a comprehensive questionnaire development framework.

Conceptual Foundations: Content and Face Validity

Content validity refers to the degree to which elements of an assessment instrument are relevant to and representative of the targeted construct for a particular assessment purpose. It is not a statistical property but is established qualitatively through structured expert judgment. The goal is to ensure the item pool comprehensively covers the entire domain of the construct without contamination from irrelevant content [8].

Face validity, often considered a superficial form of validity, assesses whether the instrument appears to measure what it is supposed to measure from the perspective of the end respondent. While not sufficient on its own, strong face validity improves participant engagement, reduces measurement error, and increases response rates, particularly for sensitive topics in reproductive health where respondent buy-in is critical [18].

The following table differentiates these key concepts:

Table 1: Distinguishing Content and Face Validity

| Aspect | Content Validity | Face Validity |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Relevance and representativeness of content to the construct | Appearance of relevance to the respondent |

| Evaluation Method | Expert judgment (quantified via CVI) | Target population feedback |

| Key Question | "Does this item validly measure part of the construct?" | "Does this item seem relevant and clear to the respondent?" |

| Outcome Metric | Content Validity Index (CVI) | Thematic analysis of feedback on relevance and comprehension |

Experimental Protocol for Establishing Content Validity

Stage 1: Defining the Construct and Generating Items

The initial stage involves a precise operational definition of the reproductive health construct to be measured.

Procedure:

- Construct Delineation: Conduct a comprehensive literature review of the construct (e.g., "behaviors to reduce exposure to EDCs in daily life") to define its boundaries and key dimensions [8].

- Item Generation: Develop a large, inclusive pool of initial items based on the literature, existing instruments, and theoretical frameworks. For a reproductive health behavior questionnaire, this may involve generating items related to specific exposure routes (food, respiration, skin) and health promotion behaviors [8].

- Item Formulation: Write clear, unambiguous, and simple items. Avoid jargon, double-barreled questions, and leading language. For sensitive topics, use neutral and non-judgmental phrasing [11].

Stage 2: Assembling the Expert Panel

The selection of a multidisciplinary expert panel is critical for robust content validity assessment.

Procedure:

- Panel Composition: Recruit 5-10 experts with diverse backgrounds relevant to the construct. For a reproductive health questionnaire, this may include clinical specialists (e.g., physicians, nurses), research methodologies, and subject-matter experts (e.g., environmental scientists, psychologists) [8].

- Expert Credentials: Ensure experts have recognized expertise in the field, evidenced by publications, clinical experience, or professional qualifications.

- Briefing: Provide experts with a clear briefing document detailing the construct definition, target population, and the purpose of the instrument.

Stage 3: Expert Rating and Quantitative Analysis

Experts systematically rate each item on its relevance to the defined construct.

Procedure:

- Rating Scale: Provide experts with a 3- or 4-point rating scale (e.g., 1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, 4 = highly relevant) [8].

- Data Collection: Use a structured survey to collect expert ratings for all items.

- Calculate Content Validity Indices (CVI):

- Item-level CVI (I-CVI): The proportion of experts giving a rating of 3 or 4 for each item. An I-CVI of 0.78 or higher is considered excellent for a panel of 5-10 experts.

- Scale-level CVI (S-CVI): The average of all I-CVIs, representing the overall content validity of the scale. A target of 0.80 or higher is recommended for newly developed instruments [8].

- Qualitative Feedback: Solicit open-ended feedback from experts on item clarity, redundancy, and suggestions for new items.

The workflow for establishing content validity, from item generation to final item selection, is a structured, iterative process, as summarized below.

Experimental Protocol for Establishing Face Validity

Stage 1: Developing the Pilot Instrument

Procedure:

- Instrument Formatting: Compile the items that have passed the content validity stage into a draft questionnaire. Use a clear layout, intuitive navigation instructions, and a consistent response scale.

- Cognitive Interview Guide: Develop a semi-structured interview guide to probe participants' understanding of items, instructions, and response options.

Stage 2: Recruiting the Target Population

Procedure:

- Participant Sampling: Recruit a small but diverse sample (e.g., n=10-15) from the instrument's intended target population [8] [18]. For a reproductive health questionnaire, ensure diversity in age, gender, socioeconomic status, and relevant health experiences.

- Informed Consent: Obtain informed consent, clearly explaining the purpose of the pilot test and the voluntary nature of participation, following IRB-approved protocols [19] [18].

Stage 3: Conducting Cognitive Interviews and Thematic Analysis

Procedure:

- Think-Aloud Protocol: Ask participants to complete the questionnaire while verbalizing their thought process. Prompt them to explain what they think each question is asking and how they decided on their answer.

- Probing Questions: After completion, use the interview guide to ask specific probes (e.g., "Can you explain that question in your own words?", "Was any wording confusing or offensive?", "How did you find the response options?").

- Data Analysis: Transcribe interviews and analyze the data using thematic analysis. Identify recurring themes related to comprehension difficulties, ambiguous terms, irrelevant content, and layout issues [18].

- Questionnaire Revision: Systematically revise the questionnaire based on the thematic analysis to improve clarity, relevance, and acceptability.

The process of establishing face validity is participatory and iterative, centering on the end-user's perspective, as shown in the following workflow.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Data from Expert Review

The following table provides a template for presenting and analyzing quantitative results from the expert content validity review, using hypothetical data from a reproductive health behavior questionnaire.

Table 2: Exemplar Content Validity Analysis for a Reproductive Health Questionnaire

| Item Number | Item Description | Expert 1 | Expert 2 | Expert 3 | Expert 4 | Expert 5 | I-CVI | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I check product labels for "BPA-free" before purchasing. | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1.00 | Retain |

| 2 | I avoid consuming food from plastic containers when possible. | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1.00 | Retain |

| 3 | I use public transportation daily. | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.20 | Discard |

| 4 | I choose personal care products labeled "paraben-free." | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1.00 | Retain |

| 5 | I air out my home to reduce indoor chemical exposure. | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1.00 | Retain |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| S-CVI/Ave | 0.90 |

Thematic Analysis from Target Population Review

The following table demonstrates how to synthesize qualitative feedback from cognitive interviews to establish face validity.

Table 3: Exemplar Thematic Analysis of Face Validity Feedback

| Theme | Illustrative Quotation | Identified Issue | Recommended Revision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jargon | "I don't know what 'endocrine-disrupting' means. It sounds scary." | Technical term not understood by laypersons. | Replace with simpler language: "chemicals that can harm your health". |

| Ambiguous Wording | " 'Often'... what does that mean? Once a week? Once a month?" | Vague frequency term. | Use specific timeframes: "In the past month, how many times...". |

| Sensitive Language | "The question about my sex life felt too direct and judgmental." | Question perceived as intrusive or offensive. | Rephrase to be more neutral and normalize the behavior. |

| Response Option Clarity | "I wanted an option between 'agree' and 'disagree'." | Limited response options force inaccurate answers. | Expand from a 4-point to a 5-point Likert scale to include "Neutral". |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential methodological components for establishing content and face validity.

Table 4: Essential Methodological Components for Validity Establishment

| Tool or Resource | Function in Validity Establishment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary Expert Panel | Provides authoritative judgment on item relevance and representativeness (content validity). | Include 5-10 experts from clinical, research, and subject-matter backgrounds. Document expertise credentials [8]. |

| Content Validity Index (CVI) | Quantifies the degree of expert consensus on item relevance. | Calculate I-CVI (per item) and S-CVI/Ave (for the scale). Use thresholds of 0.78 and 0.80, respectively [8]. |

| Cognitive Interviewing | Elicits evidence of how the target population comprehends and responds to items (face validity). | Use "think-aloud" and verbal probing techniques. Focus on identifying misinterpretation and sources of response error [18]. |

| Structured Rating Survey | Systematically collects expert ratings for CVI calculation. | Should include the construct definition, rating scale, and items. Administer via platforms like REDCap or Qualtrics for efficiency [20]. |

| Thematic Analysis Framework | Analyzes qualitative feedback from cognitive interviews to identify recurring usability issues. | Use inductive and deductive coding to systematically categorize feedback into themes like clarity, relevance, and sensitivity [21]. |

| Pilot Questionnaire | A draft version of the instrument used for face validity testing with the target population. | Should mirror the final format, including all instructions, items, and response layouts to test the full user experience [8]. |

From Items to Instrument: Scale Development and Quantitative Evaluation

Survey Administration and Sample Size Determination

Within reproductive health research, the development of validated questionnaires is fundamental for translating complex behavioral, attitudinal, and clinical observations into reliable quantitative data. This process is critical for assessing constructs such as behaviors to reduce exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) or the impact of shift work on female reproductive health [8] [22]. The administration of these surveys and the determination of an adequate sample size are not mere procedural steps; they are foundational to the statistical validity and overall scientific rigor of a study. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for these key methodological areas, framed within the context of reproductive health behavior questionnaire development.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Key Validity and Reliability Concepts for Questionnaires

For a research questionnaire to yield meaningful data, its validity and reliability must be established. Validity refers to the accuracy of a tool—whether it measures what it intends to measure. Reliability refers to the consistency of the measure over time and across different observers [1]. The table below summarizes the primary types of validity and reliability researchers must assess.

Table 1: Key Types of Questionnaire Validity and Reliability

| Type | Brief Description | Common Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Face Validity | A subjective assessment of whether the questionnaire appears to measure what it claims to. | Review by non-experts from the target audience for clarity and appropriateness. |

| Content Validity | The degree to which a tool covers all aspects of the construct it aims to investigate. | Review by a panel of subject matter experts; calculated using a Content Validity Index (CVI). |

| Construct Validity | The extent to which the tool actually measures the theoretical construct. | Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). |

| Criterion Validity | How well the tool agrees with an existing gold-standard assessment. | Correlation analysis with the validated criterion measure. |

| Internal Consistency | The extent of intercorrelations among all items within the questionnaire. | Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α); value of 0.7 or higher is typically acceptable. |

| Test-Retest Reliability | The stability of the measure over time when the characteristic is assumed to be unchanged. | Administering the same test to the same individuals after a set time interval. |

| Inter-rater Reliability | The consistency of the measure when used by different assessors. | Cohen’s kappa statistic to evaluate agreement between multiple raters. |

Fundamentals of Sample Size Determination

Sample size calculation is essential to ensure a study has a high probability of detecting a true effect if one exists, while balancing ethical and resource constraints. An inappropriately small sample size may lead to false negatives, while an excessively large one can identify statistically significant but clinically trivial effects [23]. The following elements are crucial for sample size calculation:

- Statistical Analysis Plan: The intended statistical tests (e.g., t-test, ANOVA, regression) dictate the sample size formula [23].

- Effect Size: The magnitude of the difference or relationship the study aims to detect. This is often the most challenging parameter to set and can be determined from prior literature, pilot studies, or by using conventional values (e.g., small=0.2, medium=0.5, large=0.8) [23].

- Study Power: The probability that the test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis. A power of 80% or 90% is standard [23].

- Significance Level (Alpha): The threshold for statistical significance, typically set at 0.05 [23].

- Margin of Error (Precision): Particularly for descriptive studies estimating a proportion, this defines the acceptable plus-or-minus range around the estimated value [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Questionnaire Development and Validation

The following workflow outlines the sequential steps for creating a psychometrically sound questionnaire, exemplified by studies developing reproductive health instruments [8] [22].

Diagram 1: Questionnaire Development Workflow

Phase 1: Qualitative Item Pool Development

- Objective: To define the concept and generate an initial pool of questionnaire items [22].

- Procedure:

- Data Collection: Conduct semi-structured interviews with individuals from the target population (e.g., female shift workers, couples concerned about EDC exposure) until data saturation is reached. Perform a comprehensive literature review [22].

- Data Analysis: Transcribe interviews and analyze using conventional content analysis. Identify meaning units, code them, and group codes into subcategories and main categories that represent the dimensions of the construct [22].

- Item Generation: Convert the identified categories and codes into a preliminary set of questionnaire items. Wording should be clear and precise [8].

Phase 2: Quantitative Psychometric Validation

- Objective: To refine the item pool and validate the questionnaire's psychometric properties [8] [22].

- Procedure:

- Face Validity Assessment:

- Qualitative: Ask members of the target population to evaluate items for difficulty, appropriateness, and clarity.

- Quantitative: Use the "item impact" method, where participants rate the importance of each item. Retain items with an impact score above 1.5 [22].

- Content Validity Assessment:

- Qualitative: A panel of experts (e.g., in instrument development, reproductive health) reviews the items for wording and scaling.

- Quantitative: Experts rate each item on relevance. Calculate the Item-Level Content Validity Index (I-CVI); items with an I-CVI above 0.78 are typically retained [8] [1].

- Pilot Study: Administer the questionnaire to a small sample (e.g., n=10) to identify any practical issues with administration, comprehension, or time [8].

- Construct Validity Assessment:

- Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): Administer the questionnaire to a larger sample (e.g., n=288). Use EFA (e.g., Principal Component Analysis with varimax rotation) to identify the underlying factor structure. Retain items with factor loadings >0.4 [8].

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA): Test the model derived from EFA on a separate sample or the same sample to confirm the factor structure. Use fit indices (e.g., RMSEA, SRMR) to evaluate model fit [8].

- Reliability Assessment:

- Internal Consistency: Calculate Cronbach's alpha for the entire scale and each subscale. A value of 0.7 or higher is acceptable for a new tool [8] [1].

- Stability (Test-Retest): Administer the questionnaire to the same participants after a suitable time interval (e.g., 2-3 weeks). Assess concordance using Pearson's correlation or similar methods [1].

- Face Validity Assessment:

Protocol for Sample Size Determination

The process for determining an adequate sample size varies based on the primary study design. The following workflow outlines the key steps and considerations.

Diagram 2: Sample Size Determination Workflow

A. For Descriptive Studies (e.g., Cross-Sectional Prevalence Studies)

- Objective: To estimate a population parameter (e.g., proportion, mean) with a specified level of precision [23].

- Parameters:

- Confidence Level: Typically 95%.

- Margin of Error (MoE): The acceptable deviation from the true population value (e.g., ±5%).

- Estimated Proportion (p): The expected proportion. If unknown, use 0.5 (50%) to maximize the required sample size and ensure adequacy [23].

- Calculation Formula (for a proportion):

n = (Z^2 * p * (1-p)) / e^2WhereZis the z-score for the confidence level (1.96 for 95%),pis the estimated proportion, andeis the margin of error. - Example: To estimate a prevalence with 95% confidence, a 5% MoE, and an assumed proportion of 0.5, the required sample size is

(1.96^2 * 0.5 * 0.5) / 0.05^2 = 385.

B. For Comparative Studies (e.g., Group Differences, Intervention Effects)

- Objective: To detect a specified effect size with adequate power [23].

- Parameters:

- Effect Size: The minimum difference of practical/clinical importance. This can be a standardized effect size (e.g., Cohen's d of 0.2, 0.5, 0.8 for small, medium, large effects) [23].

- Power (1-β): Usually 80% or 90%.

- Alpha (α): Usually 0.05.

- Calculation Method: Use statistical software (e.g., G*Power, OpenEpi, PS Power) and select the test corresponding to the primary analysis (e.g., t-test, chi-square test) [23].

- Example: For an independent samples t-test comparing two groups to detect a medium effect size (d=0.5) with 80% power and α=0.05, the required total sample size is 128 (64 per group) [23].

C. Adjustments and Considerations

- Dropout Rate: Inflate the calculated sample size to account for potential participant attrition. For example, if the calculated

nis 300 and a 10% dropout rate is anticipated, the final sample size should be300 / (1 - 0.10) = 334[8]. - Complex Analyses: For advanced analyses like Factor Analysis, sample size is often guided by rules of thumb, such as 5-10 participants per questionnaire item or a minimum of 300-500 participants [8] [23].

Table 2: Sample Size Requirements for Common Statistical Tests (Power=80%, α=0.05)

| Statistical Test | Effect Size | Total Sample Size | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent t-test | Small (d = 0.2) | 788 | Two groups, continuous outcome. |

| Medium (d = 0.5) | 128 | ||

| Large (d = 0.8) | 52 | ||

| Chi-square test | Small (w = 0.1) | 964 | Two groups, categorical outcome (e.g., 2x2 table). |

| Medium (w = 0.3) | 88 | ||

| Large (w = 0.5) | 32 | ||

| Correlation (Pearson's r) | Small (r = 0.1) | 782 | Tests the strength of a linear relationship. |

| Medium (r = 0.3) | 85 | ||

| Large (r = 0.5) | 29 |

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Questionnaire Development and Validation

| Item/Tool | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Expert Panel | A multi-disciplinary group of subject matter experts to assess content validity. | Evaluating the relevance and clarity of initial items for a reproductive health questionnaire [8] [22]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., IBM SPSS, AMOS, R) | Software packages used for comprehensive psychometric and statistical analysis. | Conducting Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), and calculating Cronbach's alpha [8]. |

| Sample Size Calculation Software (e.g., G*Power, OpenEpi) | Free, specialized tools for computing sample size requirements for various study designs. | Determining the minimum number of participants needed for a study comparing two groups with sufficient power [23]. |

| Pilot Sample | A small, representative subset of the target population used for preliminary testing. | Identifying ambiguous questions, estimating response time, and testing administrative procedures before full-scale deployment [8]. |

| Validated Gold-Standard Questionnaire | An existing, well-validated instrument measuring a related construct. | Assessing criterion validity by correlating scores from the new questionnaire with those from the established tool [1]. |

Psychometric Analysis and Factor Structure Identification

The development of robust, reliable, and valid questionnaires is fundamental to advancing research in sexual and reproductive health (SRH). Without rigorously validated instruments, researchers cannot accurately measure constructs, assess interventions, or compare outcomes across populations and studies. This protocol details comprehensive methodologies for the psychometric analysis and factor structure identification of SRH behavior questionnaires, providing researchers with a structured framework for measurement development and validation. The guidelines presented here are framed within a broader thesis on reproductive health questionnaire development, emphasizing standardized, evidence-based approaches that enhance measurement precision and facilitate cross-study comparisons.

The critical importance of psychometric validation is highlighted by a rapid review of sexual health knowledge tools for adolescents, which found that among sixteen identified Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs), the overall methodological quality was often "Inadequate" according to COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments) standards. This review revealed inconsistent coverage of criterion validity, responsiveness, and interpretability across existing instruments [25]. Similarly, the development of a questionnaire for assessing SRH needs of married adolescent women addressed a significant gap, as no valid and reliable instrument previously existed specifically for this population [26]. This protocol aims to address these methodological shortcomings by providing detailed, standardized approaches for psychometric validation.

Theoretical Foundations: Factor Analysis vs. Cluster Analysis

A fundamental step in psychometric analysis involves understanding the appropriate application of different statistical techniques for dimension reduction. Factor analysis and cluster analysis serve distinct purposes and answer different research questions, yet they are frequently confused in multiple behavior research [27].

Factor Analysis is a variable-centered approach that identifies latent constructs (factors) that explain patterns of covariance among observed variables. It reduces many measured variables into fewer underlying factors and assesses how well these factors explain the observed data structure. This technique is ideal when researchers aim to understand the dimensional structure of a construct or identify groups of interrelated behaviors that may share a common underlying mechanism [27].

Cluster Analysis is a person-centered approach that classifies individuals into homogeneous subgroups (clusters) based on their similarity across multiple variables. It reduces a large number of individuals into a smaller set of clusters where individuals within clusters are more similar to each other than to those in other clusters. This method is appropriate for identifying typologies or subpopulations based on specific behavioral patterns [27].

Table 1: Comparison of Factor Analysis and Cluster Analysis

| Feature | Factor Analysis | Cluster Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify latent variables that explain patterns among observed variables | Classify individuals into homogeneous subgroups |

| Focus | Variable relationships | Individual similarities |

| Research Question | "What underlying constructs explain the patterns in our data?" | "What subgroups exist in our population based on their response patterns?" |

| Data Reduction | Reduces number of variables | Reduces number of individuals |

| Outcome | Factors or components | Clusters or groups of people |

| Example Application | Identifying domains of reproductive autonomy [28] | Identifying clusters of sleep and physical activity patterns in pregnant women [29] |

The choice between these techniques has significant implications for both analysis and subsequent interventions. As demonstrated in a study of co-occurring risk behaviors, cluster analysis identified three distinct clusters of individuals: a poor diet cluster, a high-risk cluster, and a low-risk cluster. In contrast, factor analysis of the same data revealed two latent factors: substance use and unhealthy diet, demonstrating how the same dataset can yield different insights based on the analytical approach selected [27].

Phase 1: Questionnaire Development and Initial Validation

Item Generation and Content Validity

The initial phase of questionnaire development requires comprehensive item generation and rigorous content validation. The protocol for developing a questionnaire for married adolescent women's SRH needs exemplifies this process, beginning with in-depth interviews with 34 married adolescent women and four key informants, complemented by a comprehensive literature review. This qualitative phase generated 137 initial items encompassing the full spectrum of SRH needs [26].

Content validity assessment involves evaluating the relevance, comprehensiveness, and appropriateness of each item for the target construct and population. Expert review panels should assess each item for clarity, specificity, and conceptual alignment with the theoretical framework. In the married adolescent women questionnaire development, this process resulted in the refinement of the initial 137 items to a 108-item preliminary questionnaire through several modifications based on expert feedback and conceptual overlap assessment [26].

Face validity assessment ensures the questionnaire appears to measure the intended constructs from the perspective of the target population. Cognitive interviewing techniques, where participants verbalize their thought process while responding to items, are particularly valuable for identifying problematic wording, confusing response options, or sensitive items that may cause discomfort or non-response. The World Health Organization's development of the Sexual Health Assessment of Practices and Experiences (SHAPE) questionnaire employed a comprehensive multi-country cognitive interviewing study across 19 countries to refine questions and ensure cross-cultural applicability [11].

Instrument Selection and Adaptation

For researchers adapting existing instruments rather than developing new ones, careful evaluation of measurement properties is essential. The COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments) checklist provides a standardized framework for evaluating the methodological quality of existing PROMs [25]. When evaluating instruments, researchers should consider:

- Conceptual alignment with the target construct and population

- Measurement properties including reliability, validity, and responsiveness

- Linguistic and cultural appropriateness for the intended population

- Administrative feasibility in terms of length, format, and scoring requirements

The Reproductive Health Literacy Scale development demonstrates this adaptive approach, where researchers combined domains from multiple existing validated instruments: the HLS-EU-Q6 for general health literacy, eHEALS for digital health literacy, and items from the C-CLAT and a postpartum literacy scale for reproductive health-specific literacy [30].

Table 2: Selected Validated Instruments for Sexual and Reproductive Health Research

| Instrument Name | Construct Measured | Factors/ Domains | Reliability (Cronbach's α) | Sample Items/Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire for SRH Needs of Married Adolescent Women [26] | SRH needs of married adolescents | 9 domains including sexual quality of life, self-care, self-efficacy, knowledge | 0.878 (whole scale) | 74 items using Likert-scale responses |

| Reproductive Autonomy Scale (RAS) [28] | Reproductive autonomy | 3 factors: Freedom from coercion, Communication, Decision-making | 0.75 (UK validation) | Items rated on agreement scale; 3-factor structure confirmed |

| Sexual Health Questionnaire (SHQ) [25] | Sexual health knowledge | Not specified | 0.90 | Distinguished by robust construct validity (68.25% variance explained) |

| WHO SHAPE Questionnaire [11] | Sexual practices, behaviors, and health outcomes | Multiple modules including sexual problems | Implementation tested | Combination of interviewer-administered and self-administered modules |

| Reproductive Health Literacy Scale [30] | Health literacy in refugee women | 3 domains: General, digital, and reproductive health literacy | >0.7 (all domains) | Adapted from multiple validated tools; translated into multiple languages |

Phase 2: Psychometric Validation Protocol

Factor Structure Identification

Sample Size Considerations

Adequate sample size is critical for stable factor solutions. While rules of thumb vary, a minimum of 10 participants per item is often recommended for exploratory factor analysis (EFA). For confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), sample sizes of 200+ are generally recommended, though larger samples provide more stable parameter estimates. The married adolescent women questionnaire development utilized an exploratory sequential mixed methods design, with the quantitative phase including a sufficient sample size for stable factor analysis [26].

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) Protocol

Data Preparation: Screen data for missing values, outliers, and assess normality of distributions. Use appropriate missing data techniques (e.g., multiple imputation) if necessary.

Factorability Assessment: Examine the correlation matrix for sufficient correlations (≥0.30) between items. Calculate the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (values >0.60 acceptable, >0.80 good) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (should be significant, p<0.05).

Factor Extraction: Principal axis factoring or maximum likelihood estimation are commonly used. Determine the number of factors to retain using multiple criteria:

- Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues >1)

- Scree test (visual examination of the scree plot)

- Parallel analysis (comparing eigenvalues to those from random data)

Factor Rotation: Apply oblique rotation (e.g., promax) when factors are expected to correlate, or orthogonal rotation (e.g., varimax) when theoretical independence is assumed.

Interpretation and Refinement: Retain items with factor loadings ≥0.40 on primary factor and minimal cross-loadings (<0.32 on secondary factors). The married adolescent women questionnaire development removed 11 items during EFA based on these criteria, resulting in a final 74-item questionnaire categorized into nine factors [26].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive factor analysis process:

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) Protocol

Model Specification: Define the theoretical model based on EFA results or existing literature, specifying which items load on which factors.

Parameter Estimation: Use maximum likelihood estimation or robust alternatives for non-normal data.

Model Fit Assessment: Evaluate multiple fit indices:

- χ²/df ratio (<3 acceptable, <2 good)

- Comparative Fit Index (CFI >0.90 acceptable, >0.95 good)

- Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI >0.90 acceptable, >0.95 good)

- Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA <0.08 acceptable, <0.05 good)

- Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR <0.08 acceptable)

Model Modification: Use modification indices cautiously to improve model fit, with strong theoretical justification for any changes.

In the validation of the Reproductive Autonomy Scale for use in the UK, confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the three-factor structure of the scale originally identified in the US version, demonstrating cross-cultural stability of the measurement model [28].

Reliability Assessment

Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of measurement. This protocol assesses multiple forms of reliability:

Internal Consistency

Calculate Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the total scale and each subscale. Values ≥0.70 are generally acceptable for group comparisons, while ≥0.90 is preferable for individual clinical assessment. The married adolescent women questionnaire demonstrated excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.878 for the whole scale [26]. For the Reproductive Health Literacy Scale, internal consistency was maintained across multiple language versions with alpha coefficients above 0.7 for all domains [30].

Test-Retest Reliability

Administer the same questionnaire to the same participants after a sufficient time interval (typically 2-4 weeks) to assess temporal stability. Calculate the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), with values ≥0.70 indicating acceptable stability. The married adolescent women questionnaire demonstrated exceptional test-retest reliability with an ICC of 0.99 for the whole scale [26], while the Reproductive Autonomy Scale validation in the UK showed fair-good test-retest reliability with an ICC of 0.67 over a 3-month interval [28].

Additional Validity Evidence

Construct Validity

Assess relationships with other measures through hypothesis testing. For example, in the UK validation of the Reproductive Autonomy Scale, researchers tested the hypothesis that among women who want to avoid pregnancy, those with higher reproductive autonomy would be more likely to use contraception, which was supported by the data [28].

Criterion Validity

When possible, compare scores with a "gold standard" measure of the same construct. However, this is often challenging in SRH research where well-established criteria may not exist. The rapid review of sexual health knowledge tools noted that criterion validity was often neglected in existing PROMs [25].

Advanced Applications: Cluster Analysis in SRH Research

While factor analysis identifies latent constructs, cluster analysis classifies individuals based on their response patterns. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying subpopulations with distinct behavioral profiles that may require tailored interventions.

Cluster Analysis Protocol

Variable Selection: Choose variables that theoretically relate to the clustering objective. A study of sleep and physical activity patterns in pregnant women used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and International Physical Activity Questionnaire as clustering variables [29].

Data Standardization: Standardize variables to comparable scales using z-scores or other normalization techniques.

Similarity Measure Selection: Select appropriate distance measures (e.g., Euclidean, Squared Euclidean, Manhattan distance) based on variable types.

Clustering Algorithm Selection: Choose between:

- Hierarchical clustering (agglomerative or divisive)

- Partitioning methods (e.g., k-means clustering)

- Model-based methods (e.g., latent profile analysis)

Determining Number of Clusters: Use multiple criteria:

- Theoretical justification

- Dendrogram inspection (for hierarchical clustering)

- Statistical indices (e.g., elbow method, silhouette width, Bayesian Information Criterion)

Cluster Validation and Interpretation: Validate clusters through:

- Internal validation (within-cluster homogeneity, between-cluster separation)

- External validation (relationship with variables not used in clustering)

- Replication in split samples or independent datasets

In a study of Korean pregnant women, cluster analysis identified three distinct clusters: 'good sleeper' (63.4%), 'poor sleeper' (24.6%), and 'low activity' (12.0%). These clusters demonstrated differential associations with demographic factors and psychological outcomes, with the good-sleeper cluster associated with higher education and income levels, and the poor-sleeper and low-activity clusters associated with higher depressive symptoms and pregnancy stress [29].

The following diagram illustrates the cluster analysis methodology:

Comparative Analysis of Clustering Applications

Table 3: Applications of Cluster Analysis in Health Behavior Research

| Study/Application | Clustering Variables | Identified Clusters | Key Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep & Activity in Pregnancy [29] | Sleep quality, sleep duration, physical activity | 1. Good sleeper (63.4%)2. Poor sleeper (24.6%)3. Low activity (12.0%) | Good sleepers: higher education/income, healthier behaviorsPoor sleepers/low activity: higher depression/stress |

| Multiple Health Behaviors [27] | Alcohol, smoking, drug use, physical inactivity, diet | 1. Poor diet cluster2. High risk cluster3. Low risk cluster | Different demographic and psychological profiles per cluster |

| Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging [31] | Physical inactivity, unhealthy eating, smoking, alcohol use | Proposed analysis of how behaviors cluster in adults 45-85+ | Aim to inform tailored interventions for subpopulations |

Implementation Considerations and Reporting Standards