Measuring What Matters: A Guide to the Psychometric Properties of Reproductive Health Surveys

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical psychometric properties of reproductive health assessment tools.

Measuring What Matters: A Guide to the Psychometric Properties of Reproductive Health Surveys

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical psychometric properties of reproductive health assessment tools. It explores the foundational concepts of validity and reliability, details the methodological steps for scale development and application, addresses common challenges in optimization, and establishes standards for rigorous validation and cross-cultural comparison. By synthesizing current methodologies and evidence from recent studies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select, develop, and implement robust, culturally-sensitive instruments that yield reliable data for clinical research and intervention development.

Core Principles: Understanding Validity and Reliability in Reproductive Health Metrics

In the field of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) research, the quality of data and the robustness of findings are paramount. Our clinical reasoning, intervention strategies, and research conclusions can only be as strong as the tools we use for measurement [1]. Psychometrics—the field concerned with the statistical description of instrumental data and the relationships between variables—provides the foundation for ensuring that our measurement instruments are scientifically sound [1]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in SRH, understanding the core psychometric properties of validity, reliability, and responsiveness is essential for developing rigorous surveys and assessment tools that yield trustworthy, actionable data. This technical guide examines these properties within the specific context of SRH research, where measuring sensitive constructs such as contraceptive needs, service-seeking behaviors, and health outcomes requires particularly meticulous methodological approaches.

Core Psychometric Properties

Psychometric properties represent the methodological qualities of assessment tools, questionnaires, outcome measures, scales, or clinical tests [1]. In SRH research, these properties ensure that instruments developed for specific populations—such as adolescents, young adults, or specific cultural groups—generate data that accurately reflects the constructs being studied.

Validity

Validity refers to a tool's ability to measure what it is intended to measure [1]. In SRH research, this extends beyond simple face validity to encompass whether an instrument truly captures complex, multi-faceted constructs such as "contraceptive need," "service-seeking behavior," or "reproductive autonomy."

The following table summarizes the key types of validity and their application in SRH research:

Table 1: Types of Validity and Their Applications in SRH Research

| Validity Type | Definition | SRH Research Application | Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content Validity | Degree to which tool content reflects the construct of interest [1] | Ensuring SRH surveys cover all relevant topics (contraception, STIs, abortion, etc.) | Expert consensus ratings |

| Face Validity | Whether the tool appears to adequately reflect what it is supposed to measure [1] | Initial perception that SRH questions are appropriate and relevant | Stakeholder feedback |

| Construct Validity | Degree to which scores align with hypotheses based on abstract concepts [1] | Testing theoretical relationships between SRH knowledge and service utilization | Factor analysis fit indices [2] |

| Criterion Validity | How well tool measurements correlate with an established reference standard [1] | Comparing new contraceptive need measures against established indicators [3] | Correlation coefficients (r): Large ≥0.5, Moderate 0.3-0.5, Small 0.1-0.29 [2] |

| Cross-cultural Validity | Degree to which a culturally adapted tool is equivalent to the original [1] | Adapting SRH instruments for different cultural contexts while maintaining measurement properties | Measurement invariance statistics |

Recent innovations in SRH measurement highlight the evolving nature of validity. The Guttmacher Institute's "Adding It Up 2024" report introduces a new "unmet demand" measure for contraception that better aligns with rights-based, person-centered approaches by incorporating women's expressed intentions to use contraception, moving beyond assumptions based solely on pregnancy desires [3].

Reliability

Reliability refers to the extent to which a measurement is consistent and free from error [1]. In SRH research, this ensures that instruments yield stable results across different administrators, time points, and population subgroups. Reliability is not a fixed property but varies based on the instrument's application context and population [1].

Table 2: Reliability Types and Assessment Methods in SRH Research

| Reliability Type | Definition | Assessment Method | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Consistency | Degree of inter-relatedness among items | Cronbach's Alpha | Excellent ≥0.80, Adequate 0.60-0.79, Poor <0.60 [2] |

| Test-Retest | Stability of scores when patients self-evaluate at two separate occasions [1] | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Excellent ≥0.80, Good 0.60-0.79, Poor <0.60 [2] |

| Inter-rater | Agreement between different evaluators at the same time [1] | ICC or Kappa for categorical data | Excellent ≥0.80, Good 0.60-0.79, Poor <0.60 [2] |

| Intra-rater | Consistency of the same evaluator over time [1] | ICC or Kappa for categorical data | Excellent ≥0.80, Good 0.60-0.79, Poor <0.60 [2] |

The Total Teen Assessment validation study exemplifies comprehensive reliability testing in SRH research, employing a three-phase psychometric development process that included factor analysis to establish internal consistency across sexual health, mental health, and substance use domains [4].

Responsiveness

Responsiveness, also known as sensitivity to change, is an instrument's ability to detect clinically important changes over time, particularly in response to effective therapeutic interventions [1]. In SRH research, this property is crucial for evaluating whether interventions (such as educational programs or service delivery improvements) actually produce meaningful changes in knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors.

A tool is considered sensitive to change if it can precisely measure increases and decreases in the construct measured following an intervention [1]. Common indices of responsiveness include:

- Effect size with pooled or baseline standard deviation

- Standardized response mean

- Guyatt responsiveness index

- Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves [2]

The relationship between different measurement precision concepts can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Protocols for Psychometric Validation

Robust psychometric validation requires structured methodological approaches. The following protocols outline key processes for establishing instrument validity and reliability in SRH research.

Scale Development and Validation Protocol

The development of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Seeking Scale (SRHSSS) exemplifies a comprehensive validation methodology [5]:

Phase 1: Conceptualization and Item Development

- Conduct literature review to define construct boundaries

- Administer preliminary questionnaires to target population (n=98 in SRHSSS development)

- Conduct focus group interviews (n=8) to identify relevant themes and terminology

- Draft initial item pool with attention to including both positive and negative statements

- Ensure each item contains only one judgment/thought

Phase 2: Content Validation

- Engage expert evaluation (e.g., psychiatric nursing, obstetrics/gynecology nursing specialists)

- Assess content validity through structured expert ratings

- Obtain language expert review to ensure clarity and appropriateness

- Conduct pre-test with target population (n=15) to assess comprehensibility

- Refine items based on cognitive interviewing feedback

Phase 3: Psychometric Testing

- Administer scale to large sample (n=458 in SRHSSS study)

- Perform exploratory factor analysis to examine construct validity

- Calculate variance explained by extracted factors (89.45% in SRHSSS)

- Assess factor loadings (0.78-0.97 in SRHSSS)

- Establish reliability through Cronbach's alpha (α=0.90 in SRHSSS)

- Conduct test-retest reliability with sub-sample (n=220) at one-month interval

Electronic Assessment Implementation Protocol

The Total Teen Assessment validation study demonstrates specialized protocols for electronic SRH assessment [4]:

Workflow Integration

- Implement tablet-based administration to ensure confidentiality

- Utilize skip logic to display relevant questions based on responses

- Automatically generate scores in youth-friendly format immediately after completion

- Classify patients into no-to-low or moderate-to-high need categories for clinical intervention

Stakeholder Engagement

- Conduct focus groups with youth (n=8) via Zoom to gather feedback on assessment

- Ensure representation across diverse demographics (ages 12-17, multiple states)

- Facilitate discussion of content coverage, format, verbiage, clarity, and length

- Collaborate iteratively with healthcare professionals serving adolescents

- Incorporate feedback from project advisory committee including youth representatives

Successful psychometric validation in SRH research requires specific methodological resources and approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Psychometric Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Application in SRH Research |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, SPSS, Mplus | Conduct factor analysis, ICC calculations, reliability testing |

| Reliability Analysis | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), Cronbach's Alpha, Kappa Statistics | Quantify measurement consistency across raters and time [1] [2] |

| Validity Assessment | Exploratory/Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Principal Component Analysis | Establish construct validity, examine dimensionality [2] [5] |

| Participant Engagement | Financial incentives (e.g., $25 gift cards), Multiple contact methods, Trusted adult contacts | Maintain high response rates in longitudinal SRH studies [6] |

| Cross-cultural Adaptation | Translation/back-translation, Cognitive interviewing, Measurement invariance testing | Ensure equivalence of SRH instruments across cultural contexts [1] |

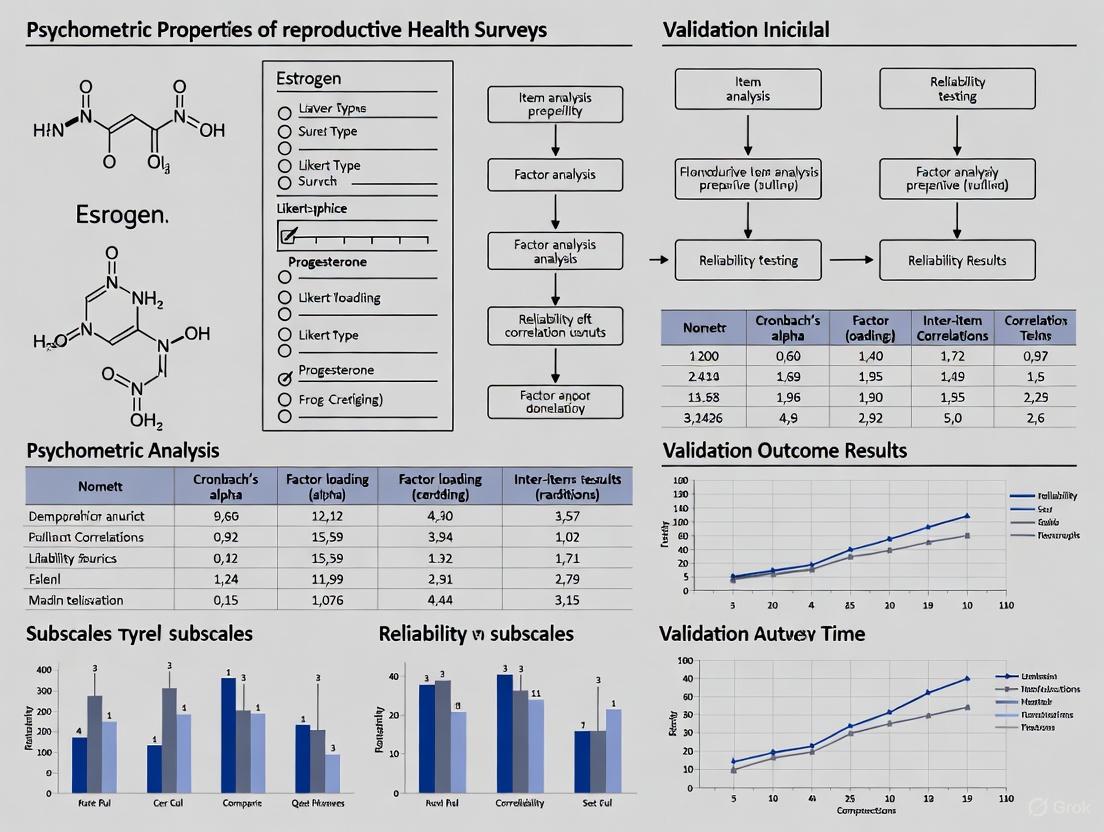

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing and validating SRH instruments:

In reproductive health survey research, rigorous attention to psychometric properties is not merely methodological refinement but an ethical imperative. The sensitive nature of SRH data, coupled with the profound implications for policy and clinical practice, demands instruments of the highest scientific quality. As the field evolves toward more person-centered measurement approaches—exemplified by innovations such as the "unmet demand" contraceptive need metric—the fundamental requirements for validity, reliability, and responsiveness remain cornerstones of scientific rigor [3]. By adhering to comprehensive validation protocols, employing appropriate statistical methodologies, and actively engaging target populations throughout the development process, SRH researchers can ensure their measurement tools generate the trustworthy evidence necessary to advance sexual and reproductive health and rights globally.

This technical guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with an in-depth analysis of three fundamental psychometric indicators—Cronbach's alpha, Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and Factor Analysis—within the context of reproductive health survey research. Ensuring the reliability and validity of assessment tools is paramount in producing scientifically rigorous and clinically meaningful data. This whitepaper delineates the theoretical underpinnings, calculation methodologies, interpretation guidelines, and application protocols for each indicator, supported by contemporary research examples and standardized data presentation tables to facilitate implementation in psychometric validation studies.

Reproductive health surveys are critical instruments for assessing sensitive constructs such as reproductive autonomy, sexual health, and patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials and public health interventions. The validity of conclusions drawn from these tools hinges on their psychometric properties, primarily reliability (consistency of measurement) and validity (accuracy in measuring the intended construct) [7] [8]. Within this framework, Cronbach's alpha serves as a key metric for internal consistency, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) evaluates score stability over time or across raters, and factor analysis provides evidence for the underlying structural validity. These indicators are not standalone metrics but interconnected components of a comprehensive validation strategy, particularly crucial when adapting existing scales for new populations or developing novel instruments for specific clinical groups, such as women with premature ovarian insufficiency or other reproductive health conditions [9] [10].

Cronbach's Alpha: Assessing Internal Consistency

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation

Cronbach's alpha (α) is a coefficient of internal consistency that estimates how closely related a set of items are as a group [11] [12]. It is founded on the concept that items designed to measure the same underlying construct should produce similar scores. The coefficient is calculated as a function of the number of test items and the average inter-correlation among these items.

The standard formula for Cronbach's alpha is: [ \alpha = \frac{N \bar{c}}{\bar{v} + (N-1) \bar{c}} ] Where:

- ( N ) = number of items

- ( \bar{c} ) = average inter-item covariance

- ( \bar{v} ) = average variance [11]

Alpha can also be conceptualized as the average of all possible split-half reliabilities within an instrument [13]. Higher alpha values indicate greater internal consistency, with values closer to 1.0 suggesting that the items reliably measure the same underlying construct.

Interpretation Guidelines and Application

Established benchmarks for interpreting Cronbach's alpha are detailed in Table 1. These thresholds provide researchers with standardized criteria for evaluating the internal consistency of their instruments.

Table 1: Interpretation Guidelines for Cronbach's Alpha

| Alpha Value Range | Interpretation | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.50 | Unacceptable | Revise or discard the scale |

| 0.51 - 0.60 | Poor | Substantial revision needed |

| 0.61 - 0.70 | Questionable | May require item modification |

| 0.71 - 0.80 | Acceptable | Appropriate for research use |

| 0.81 - 0.90 | Good | Good internal consistency |

| 0.91 - 0.95 | Excellent | Possible item redundancy |

| > 0.95 | Potentially problematic | Likely item redundancy [7] [8] |

In reproductive health research, Cronbach's alpha has been successfully employed to validate key instruments. For instance, the Reproductive Autonomy Scale (RAS) demonstrated good internal consistency with a Cronbach's α of 0.75 in a UK validation study [9]. Similarly, the Sexual and Reproductive Health Assessment Scale for women with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (SRH-POI) showed strong internal consistency with α = 0.884 [10].

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Internal Consistency

Objective: To determine the internal consistency of a multi-item reproductive health survey instrument.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Dataset containing respondent scores for all items

- Statistical software (e.g., SPSS, R, Stata)

- Documentation of the instrument's theoretical construct

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile respondent data in a structured format with rows representing participants and columns representing item scores.

- Preliminary Checks: Ensure all items are measured on the same scale and coded consistently.

- Software Analysis:

- In SPSS: Navigate to

Analyze > Scale > Reliability Analysis - Select all target items for the scale

- In the

Statisticsdialog, selectInter-item Correlations[7]

- In SPSS: Navigate to

- Output Interpretation:

- Record the overall Cronbach's alpha value

- Examine "alpha if item deleted" statistics to identify problematic items

- Review inter-item correlation matrix (optimal range: 0.15-0.50) [12]

Troubleshooting:

- If alpha is unacceptably low (<0.70), examine items with low item-total correlations (<0.30) for potential revision or removal

- If alpha is excessively high (>0.95), check for redundant items with nearly identical wording or content

Figure 1: Cronbach's Alpha Assessment Workflow

Limitations and Considerations

While Cronbach's alpha is widely used, several limitations warrant consideration:

- Sensitivity to Scale Length: Alpha tends to increase with more items, potentially inflating reliability estimates for longer scales [8]

- Dimensionality Assumption: Alpha assumes unidimensionality but cannot confirm it; high alpha doesn't guarantee the scale measures a single construct [8]

- Tau-Equivalence: Alpha requires items to measure the same construct on the same scale; violations can lead to reliability underestimation [8]

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC): Evaluating Reliability

Theoretical Foundations and ICC Forms

The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) is a versatile reliability statistic used to assess consistency or agreement between measurements, particularly in test-retest, inter-rater, and intra-rater reliability analyses [14] [7]. Unlike Pearson's correlation, which only measures linear relationship, ICC incorporates both correlation and agreement, making it more appropriate for reliability assessment [14].

ICC calculations are based on variance components derived from analysis of variance (ANOVA): [ ICC = \frac{\sigma{\alpha}^{2}}{\sigma{\alpha}^{2} + \sigma_{\varepsilon}^{2}} ] Where:

- (\sigma_{\alpha}^{2}) = variance between subjects (true variance)

- (\sigma_{\varepsilon}^{2}) = variance within subjects (error variance) [15]

McGraw and Wong defined 10 forms of ICC based on three key considerations, outlined in Table 2.

Table 2: Selection Framework for ICC Forms

| Selection Factor | Options | Appropriate ICC Form |

|---|---|---|

| Model | One-way random effects | Different raters for each subject |

| Two-way random effects | Raters randomly selected from population | |

| Two-way mixed effects | Specific raters of interest only | |

| Type | Single rater/measurement | Reliability of typical single rater |

| Mean of k raters/measurements | Reliability of averaged ratings | |

| Definition | Consistency | Relative agreement allowing additive differences |

| Absolute agreement | Exact score agreement required [14] |

Interpretation Guidelines and Application

ICC values are interpreted using standardized benchmarks that indicate the degree of reliability, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: ICC Interpretation Guidelines

| ICC Value Range | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.50 | Poor | Unacceptable for clinical or research use |

| 0.50 - 0.75 | Moderate | Acceptable for group-level comparisons |

| 0.76 - 0.90 | Good | Suitable for individual-level assessment |

| > 0.90 | Excellent | Ideal for high-stakes clinical decision making [14] [7] |

In reproductive health research, ICC has been effectively implemented for test-retest reliability assessment. The UK validation of the Reproductive Autonomy Scale reported "fair-good" test-retest reliability with an ICC of 0.67 [9]. The SRH-POI instrument demonstrated excellent temporal stability with an ICC of 0.95 for the entire scale [10].

Experimental Protocol for Test-Retest Reliability Using ICC

Objective: To evaluate the stability of a reproductive health survey instrument over time.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Validated survey instrument

- Participant cohort representative of target population

- Statistical software with ANOVA and ICC capabilities

Procedure:

- Study Design:

- Administer the instrument to participants at time point 1 (T1)

- Schedule follow-up administration at time point 2 (T2)

- Determine appropriate interval based on construct stability (typically 1-4 weeks for reproductive health attitudes) [7]

- Data Collection:

- Ensure consistent administration conditions

- Maintain identical instrument format and instructions

- Statistical Analysis:

- In SPSS:

Analyze > Scale > Reliability Analysis - Select both time points as items

- In

Statistics, selectIntraclass Correlation Coefficient - Choose appropriate model based on study design [7]

- In SPSS:

- Model Selection Guidance:

- For test-retest: Two-way mixed effects, absolute agreement, single rater (ICC(3,1))

- For inter-rater with random raters: Two-way random effects, absolute agreement, single rater (ICC(2,1))

Reporting Standards:

- Specify the ICC model, type, and definition used

- Report 95% confidence intervals for ICC estimates

- Include both single-measure and average-measure ICC when appropriate

Figure 2: ICC Assessment Workflow for Test-Retest Reliability

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

- Inappropriate Time Interval: Too short may introduce memory effects; too long may capture genuine construct change

- Incorrect Model Selection: Carefully consider whether raters are random or fixed effects based on research question

- Ignoring Context: Clinical decision-making requires higher ICC thresholds (>0.90) than group-level research (>0.70)

Factor Analysis: Establishing Structural Validity

Theoretical Foundations and Types

Factor analysis is a multivariate statistical method used to identify the latent constructs (factors) that explain the pattern of correlations within a set of observed variables [16]. In scale development, it serves to verify the hypothesized structure of an instrument and provide evidence for construct validity.

The fundamental factor analysis model represents each observed variable as a linear combination of underlying factors: [ Xi = \lambda{i1}F1 + \lambda{i2}F2 + ... + \lambda{im}Fm + \varepsiloni ] Where:

- ( X_i ) = observed variable i

- ( \lambda_{ij} ) = factor loading of variable i on factor j

- ( F_j ) = latent factor j

- ( \varepsilon_i ) = unique variance (measurement error) [16]

Two primary approaches to factor analysis are employed in psychometric validation:

- Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): Used when the underlying factor structure is unknown or not well-established

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA): Used to test a pre-specified factor structure based on theory or previous research [16]

Key Concepts and Interpretation

Factor Loadings: Correlation coefficients between observed variables and latent factors, with absolute values >0.4 generally considered meaningful [16]

Eigenvalues: Represent the amount of variance explained by each factor, with values >1.0 indicating factors that explain more variance than a single observed variable (Kaiser's criterion) [16]

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure: Assesses sampling adequacy, with values >0.80 considered meritorious for factor analysis

In reproductive health research, factor analysis has been instrumental in validating instrument structure. The SRH-POI scale development employed EFA, reporting KMO=0.83 and a significant Bartlett's test of sphericity, ultimately confirming a 4-factor structure with 30 items [10].

Experimental Protocol for Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Objective: To verify the hypothesized factor structure of a reproductive health measurement instrument.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Complete dataset from instrument administration

- Statistical software with CFA capabilities (e.g., SPSS Amos, R lavaan, Mplus)

- A priori hypothesized factor model based on theory or EFA

Procedure:

- Data Screening:

- Check for multivariate normality and outliers

- Assess missing data patterns

- Verify adequate sample size (minimum 10:1 participant to variable ratio) [16]

- Model Specification:

- Define latent factors based on theoretical constructs

- Specify which items load on which factors

- Allow correlation between factors unless theoretical justification exists for orthogonality

- Model Estimation:

- Use Maximum Likelihood estimation for continuous data

- Assess model fit using multiple indices (see Table 4)

- Model Evaluation and Modification:

- Examine factor loadings for statistical and practical significance

- Review modification indices for potential model improvements

- Test alternative nested models if theoretically justified

Table 4: CFA Model Fit Indices and Interpretation

| Fit Index | Excellent Fit | Acceptable Fit | Calculation/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ²/df | < 2 | < 3 | Sensitive to sample size |

| CFI | > 0.95 | > 0.90 | Compares to null model |

| TLI | > 0.95 | > 0.90 | Less sensitive to model complexity |

| RMSEA | < 0.05 | < 0.08 | Penalizes model complexity |

| SRMR | < 0.05 | < 0.08 | Standardized residual mean |

Application in Reproductive Health Research

The three-factor structure of the Reproductive Autonomy Scale was confirmed using CFA in its UK validation, providing robust evidence for its structural validity [9]. Similarly, the SRH-POI instrument development employed factor analysis to refine an initial 84-item pool down to a concise 30-item scale with clear factor structure [10].

Figure 3: Factor Analysis Decision Workflow

Integrated Application in Reproductive Health Research

Sequential Validation Framework

A comprehensive psychometric validation follows a logical sequence where each indicator informs the next, creating a robust chain of evidence for instrument quality. Figure 4 illustrates this integrated approach.

Figure 4: Sequential Psychometric Validation Framework

Table 5: Essential Methodological Components for Psychometric Validation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Data analysis and psychometric calculations | SPSS Reliability Analysis module for Cronbach's alpha and ICC [11] [7] |

| Participant Cohort | Source of response data for validation | Representative sample of target population (e.g., women of reproductive age for RAS validation) [9] |

| Validated Reference Instruments | Establishing convergent validity | Well-validated measures of related constructs for correlation analysis |

| Documentation Protocol | Ensuring methodological transparency | Detailed recording of model specifications, ICC forms, and factor rotation methods |

Case Example: Reproductive Autonomy Scale Validation

The UK validation of the Reproductive Autonomy Scale exemplifies the integrated application of these psychometric indicators [9]:

- Internal Consistency: Cronbach's α = 0.75 demonstrated acceptable reliability

- Factor Structure: Confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the hypothesized three-factor structure

- Test-Retest Reliability: ICC = 0.67 indicated fair-good temporal stability

- Construct Validity: Hypothesis testing confirmed that women wanting to avoid pregnancy with higher reproductive autonomy scores were more likely to use contraception

This comprehensive validation approach supported the RAS as a scientifically sound tool for research, clinical practice, and policy development in reproductive health.

Cronbach's alpha, ICC, and factor analysis constitute essential indicators of a robust psychometric instrument in reproductive health research. When applied systematically and interpreted according to established guidelines, these statistical tools provide compelling evidence for the reliability and validity of assessment instruments. The integrated application of these methods, as demonstrated in contemporary reproductive health research, ensures that resulting data are scientifically rigorous and clinically meaningful. Future directions in psychometric validation may incorporate more advanced statistical approaches, but these fundamental indicators will continue to form the cornerstone of instrument validation in reproductive health survey research.

The Critical Role of Content Validity in Culturally-Sensitive Contexts

In the field of reproductive health research, the psychometric properties of survey instruments fundamentally determine the quality and applicability of collected data. Among these properties, content validity—the degree to which an instrument adequately covers the target construct—is paramount, particularly when researching culturally diverse populations. Without strong content validity, even statistically reliable measures may fail to capture culturally-specific manifestations of health phenomena, leading to flawed conclusions and ineffective interventions. This technical guide examines the critical role of content validity within culturally-sensitive research contexts, providing methodological frameworks and experimental protocols essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in global reproductive health.

The development of the MatCODE and MatER tools for assessing Spanish women's knowledge of healthcare rights and perception of resource scarcity during maternity exemplifies rigorous content validation. These instruments underwent systematic expert evaluation using Aiken's V coefficient and content validity index (CVI), achieving values >0.80, thus establishing robust content validity before field implementation [17]. Similarly, when adapting the Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI) for Iranian populations, researchers identified varying content validity ratios across cultural domains, with particularly challenging items in "cultural perception of the context" and "cultural factors affecting help-seeking" [18]. These cases underscore how cultural context directly influences what constitutes valid content across different populations.

Conceptual Foundations of Content Validity in Cultural Contexts

Defining Content Validity Beyond Linguistic Translation

Content validity in culturally-sensitive research extends far beyond simple linguistic translation of instruments. It requires conceptual equivalence—ensuring that constructs hold similar meaning and relevance across cultural contexts. For reproductive health surveys, concepts like "family planning," "sexual health," or "maternal well-being" may manifest differently across cultural frameworks, necessitating deep conceptual validation rather than superficial translation.

The cultural adaptation of the Cultural Awareness Scale (CAS) for Polish nursing students illustrates this comprehensive approach. Researchers followed WHO guidelines for cultural and linguistic adaptation, which included not just translation but also evaluation of conceptual relevance to the Polish healthcare context [19]. This process recognized that cultural competence components might carry different weights and manifestations in Poland's specific multicultural landscape, particularly following increased migration from Ukraine and other countries.

Theoretical Frameworks for Cultural Validity

Several theoretical frameworks inform content validation in culturally-sensitive research. The Campinha-Bacote model of cultural competence, which conceptualizes cultural awareness, knowledge, skills, encounters, and desire as interconnected components, provided the theoretical foundation for the Cultural Awareness Scale [19]. This model emphasizes that content validity must address multiple dimensions of cultural experience rather than treating culture as a monolithic variable.

Similarly, the person-centered maternity care framework underpinning the MatCODE instrument recognizes that women's participation and evaluation of their needs are essential components of maternity care quality [17]. This framework necessitated including items that captured culturally-specific expressions of autonomy and rights within Spanish healthcare settings, demonstrating how theoretical orientation directly shapes content validity requirements.

Methodological Protocols for Establishing Content Validity

Expert Panel Evaluation Protocols

Systematic expert evaluation constitutes the cornerstone of establishing content validity in culturally-sensitive instruments. The following table summarizes quantitative benchmarks from recent reproductive health validation studies:

Table 1: Content Validity Benchmarks in Reproductive Health Instrument Development

| Instrument | Cultural Context | Validation Metric | Result | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatCODE/MatER | Spanish maternity care | Aiken's V | >0.80 | Excellent validity [17] |

| WSW-RHQ | Iranian shift workers | CVR | >0.64 | Acceptable [20] |

| Fertility Knowledge Inventories | Iranian couples | CVI | 0.90-0.95 | Excellent [21] |

| Cultural Formulation Interview | Iranian population | CVI | 0.51 | Requires improvement [18] |

| Sexual Health Questionnaire | Adolescents | Construct Validity | 68.25% variance | Robust [22] |

Expert Recruitment and Composition

Expert panels must demonstrate both methodological expertise and cultural representativeness. The validation of the Women Shift Workers' Reproductive Health Questionnaire involved twelve experts from midwifery, gynecology, and occupational health, ensuring multidisciplinary perspective on reproductive health content [20]. Similarly, the Cultural Formulation Interview validation employed a diverse panel including psychiatrists, psychologists, sociologists, social workers, and even patients to capture multiple dimensions of cultural validity [18].

The composition of expert panels should reflect the cultural ecosystems in which instruments will be deployed. For the Polish Cultural Awareness Scale adaptation, experts needed understanding of both nursing education standards and Poland's specific multicultural context, particularly regarding Ukrainian migrant populations [19].

Quantitative Evaluation Procedures

The content validity index (CVI) calculation follows specific methodological protocols. For each item, experts rate relevance on a 4-point scale (1=not relevant, 4=highly relevant). The CVI is calculated as the number of experts rating the item 3 or 4, divided by the total number of experts. The universal agreement CVI (UA-CVI) calculates the proportion of items rated 3 or 4 by all experts [17].

Aiken's V coefficient provides another quantitative approach, particularly useful for smaller expert panels. This statistic quantifies the agreement among experts regarding an item's relevance, clarity, and coherence, with values >0.80 indicating strong content validity [17].

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Content Validity Assessment

| Parameter | Calculation Method | Interpretation Threshold | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content Validity Index (CVI) | Proportion of experts giving rating ≥3 | ≥0.78 per item; ≥0.90 overall | Item-level relevance assessment |

| Aiken's V | V = (Σ(r - lo)/(n(c - lo)) | >0.80 acceptable | Small expert panels (3-5 experts) |

| Content Validity Ratio (CVR) | CVR = (ne - N/2)/(N/2) | ≥0.62 for 10 experts | Essentiality assessment |

| Kappa Coefficient | (I-CVI - pc)/(1 - pc) | >0.74 excellent | Chance-corrected agreement |

Target Population Engagement Protocols

Content validity requires participant feedback on instrument comprehensibility, relevance, and cultural appropriateness. The MatCODE validation employed a pilot cohort of 27 women who assessed the understandability of questionnaires using the INFLESZ scale, a validated Spanish tool for evaluating text readability [17]. This demonstrated semantic understanding at the target population level before full-scale deployment.

The development of a sexual and reproductive health needs assessment for married adolescent women in Iran involved in-depth interviews with 34 married adolescent women and four key informants during item generation [23]. This qualitative exploration ensured that items reflected the lived experiences and specific needs of this unique population, whose SRH needs differ from both adult women and unmarried adolescents.

Experimental Workflow for Cultural Validation

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for establishing content validity in culturally-sensitive instruments:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Content Validation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Assessment Tools | Aiken's V Calculator, CVI Spreadsheet | Quantifying expert agreement on item relevance | MatCODE validation achieving Aiken's V >0.80 [17] |

| Readability Instruments | INFLESZ Scale, Flesch-Kincaid Tests | Assessing comprehensibility for target population | Spanish maternity tool testing with INFLESZ [17] |

| Qualitative Analysis Frameworks | Thematic Analysis, Content Analysis | Identifying culturally-specific constructs | Married adolescent women SRH needs assessment [23] |

| Psychometric Validation Software | R psych package, SPSS FACTOR, Mplus | Conducting factor analysis and reliability testing | Female Fertility Knowledge Inventory validation [21] |

| Cross-Cultural Adaptation Guidelines | WHO Translation Guidelines, COSMIN Checklist | Standardizing cultural adaptation process | Polish CAS adaptation following WHO protocols [19] |

Advanced Considerations in Cultural Validation

Addressing Measurement Invariances

Advanced content validation must consider measurement invariance—whether instruments function equivalently across cultural subgroups. The rapid review of sexual health knowledge tools for adolescents found inconsistent attention to measurement invariance, with only 5 of 14 studies addressing hypothesis testing about group differences [22] [24]. Establishing content validity prerequisites subsequent tests of measurement invariance through multi-group confirmatory factor analysis.

Navigating Cultural Paradoxes in Instrument Design

Cultural validation sometimes reveals paradoxical requirements where instruments must balance seemingly contradictory attributes. The Cultural Sensibility Scale for Nursing (CUSNUR) needed to assess both universal nursing competencies and culture-specific adaptations, requiring items that captured this nuanced balance [25]. Similarly, reproductive health surveys must often navigate tensions between standardized measurement (enabling cross-cultural comparison) and cultural specificity (ensuring local relevance).

Content validity represents the foundational psychometric property without which other measurement properties become irrelevant, particularly in culturally-sensitive reproductive health research. The methodologies and protocols outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with evidence-based approaches for establishing robust content validity across cultural contexts. As global reproductive health challenges require increasingly sophisticated measurement approaches, the rigorous cultural validation of research instruments will remain essential for generating meaningful data, developing effective interventions, and advancing equitable health outcomes across diverse populations. Future directions should emphasize mixed-methods validation approaches that integrate quantitative metrics with qualitative insights, and dynamic validation frameworks that recognize cultural contexts as evolving rather than static.

Within the critical field of reproductive health research, the development and validation of robust measurement instruments are foundational to generating reliable evidence. This technical guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for establishing construct validity—a core psychometric property. Grounded in the context of reproductive health survey research, this whitepaper delineates a systematic pathway from theoretical conceptualization to quantitative measurement validation. Through detailed protocols, structured data presentation, and visual workflows, we equip scientists with practical methodologies to ensure their instruments accurately capture the complex, latent constructs inherent to sexual and reproductive health.

Theoretical Foundations of Construct Validity

In psychometrics, a construct is an abstract concept, characteristic, or variable that cannot be directly observed but is measured through indicators and manifestations [26]. In reproductive health research, quintessential constructs include reproductive autonomy, sexual assertiveness, and health service-seeking behavior.

Construct validity is the degree to which an instrument truly measures the theoretical construct it purports to measure [26] [27] [28]. It is not a single test but an ongoing process of accumulating evidence to support the inference that a test score accurately represents the intended construct. This is paramount in reproductive health, where constructs are often sensitive, multi-faceted, and heavily influenced by socio-cultural norms. For instance, measuring "reproductive autonomy" requires ensuring a scale captures a person's control over contraceptive use and childbearing, rather than their general assertiveness or knowledge [9].

Within a broader validation framework, construct validity is supported by other validity types, each providing a unique form of evidence (See Table 1).

Table 1: Types of Validity Evidence in Psychometric Research

| Validity Type | Definition | Key Question | Common Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construct Validity | The extent to which a test measures the theoretical construct it is intended to measure [26]. | Does this test measure the concept of interest? | Hypothesis testing, Factor Analysis [9] [29]. |

| Content Validity | The degree to which a test is systematically representative of the entire domain of the construct [26] [27]. | Does the test fully cover all relevant aspects of the construct? | Expert panel review (CVI, CVR) [29] [20]. |

| Face Validity | A subjective judgment of whether the test appears to measure what it claims to [26] [27]. | Does the test look like it measures the construct? | Informal review by target population or experts. |

| Criterion Validity | The extent to which test scores correlate with an external "gold standard" measure of the same construct [26] [28]. | Do the results correspond to a known standard? | Correlation analysis (e.g., Pearson's r) with a benchmark. |

Methodological Pathways for Establishing Construct Validity

Establishing construct validity is a multi-stage process that integrates qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The following workflow and subsequent protocols outline a comprehensive approach.

Figure 1: A Sequential Workflow for Establishing Construct Validity in Instrument Development.

Phase 1: Content and Face Validity Assessment

Objective: To ensure the initial item pool is relevant, representative, and clear to the target population.

Experimental Protocol:

Expert Panel Review (Content Validity):

- Participants: Assemble a panel of 8-12 experts in the field (e.g., reproductive health, psychometrics, clinical medicine) [20].

- Procedure: Experts evaluate each item for relevance, clarity, and comprehensiveness using a structured form.

- Quantitative Metrics:

- Content Validity Ratio (CVR): Assesses the essentiality of each item. Lawshe's table provides minimum values (e.g., 0.62 for 10 experts) [29].

- Content Validity Index (CVI): Measures the proportion of experts agreeing on an item's relevance. An item-level CVI (I-CVI) ≥ 0.78 is acceptable, and the scale-level average (S-CVI) should be ≥ 0.90 [29] [20].

- Outcome: Items with poor metrics are revised or discarded.

Target Population Review (Face Validity):

- Participants: A small sample (e.g., n=10) from the intended study population [30] [20].

- Procedure: Participants complete the draft scale and are interviewed about the clarity, difficulty, and appropriateness of each item.

- Quantitative Metric: Item Impact Score is calculated to identify items with low perceived importance [29] [20].

- Outcome: Wording is refined for clarity and cultural appropriateness.

Phase 2: Pilot Testing and Item Analysis

Objective: To refine the scale using statistical methods on a preliminary dataset.

Protocol:

- Sample: Administer the scale to a small but sufficient sample (typically 50-100 participants) [20].

- Analysis: Conduct item analysis to calculate:

- Item-Total Correlation: The correlation between each item and the total scale score. Values below 0.3 may indicate the item is not measuring the same construct [20].

- Inter-Item Correlation: The average correlation among all items.

- Cronbach's Alpha: A preliminary measure of internal consistency. A value > 0.7 is generally desired for group-level analysis [20].

Phase 3: Construct Validity Assessment via Factor Analysis

This is the core quantitative phase for evaluating construct validity.

Protocol 1: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

- Objective: To uncover the underlying factor structure of the scale without pre-defined constraints.

- Sample Size: A minimum of 5-10 participants per item is a common rule of thumb [20].

- Procedure:

- Sampling Adequacy: Check the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure; a value > 0.8 is good [20]. Bartlett's Test of Sphericity should be significant (p < .05).

- Factor Extraction: Use Principal Component Analysis or Maximum Likelihood estimation.

- Factor Retention: Determine the number of factors using eigenvalues > 1.0 and scree plot inspection.

- Rotation: Apply an orthogonal (e.g., Varimax) or oblique (e.g., Promax) rotation to simplify the factor structure and enhance interpretability.

- Interpretation: Items with factor loadings > |0.4|–|0.5| are typically considered to load significantly on a factor. The resulting factors should align with the theoretical dimensions of the construct.

Protocol 2: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

- Objective: To statistically test how well the pre-specified factor structure (e.g., from EFA or theory) fits the observed data.

- Sample: A new, independent sample is ideal.

- Procedure: The hypothesized model is tested using structural equation modeling.

- Model Fit Indices: Assess fit using multiple indices [20]:

- Chi-Square/df (CMIN/DF): < 3.0 indicates good fit.

- Comparative Fit Index (CFI): > 0.90 (preferably > 0.95).

- Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA): < 0.08 (preferably < 0.06).

- Outcome: A well-fitting model provides strong evidence for the construct validity of the proposed factor structure.

Phase 4: Reliability and Stability Assessment

Objective: To establish the consistency and reproducibility of the scale scores.

Protocol:

- Internal Consistency: Calculate Cronbach's alpha for the total scale and its subscales. A value between 0.70 and 0.95 is generally considered acceptable, indicating that the items are consistently measuring the same construct [31] [27] [28].

- Test-Retest Reliability:

Applied Case Studies in Reproductive Health Research

The following table summarizes how the aforementioned protocols have been successfully implemented to establish construct validity in recent reproductive health research.

Table 2: Case Studies of Construct Validity Establishment in Reproductive Health Instrument Development

| Instrument / Study | Target Population | Factor Analysis Method & Results | Reliability Metrics | Key Validity Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Autonomy Scale (RAS) for use in the UK [9] | Women of reproductive age, UK | Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA): Confirmed the original 3-factor structure from the US version. | Cronbach's α: 0.75Test-Retest ICC: 0.67 | Hypothesis Testing: Confirmed that women wanting to avoid pregnancy but with higher RAS scores were more likely to use contraception. |

| Women Shift Workers’ Reproductive Health Questionnaire (WSW-RHQ) [20] | Women shift workers, Iran | EFA & CFA: EFA revealed a 5-factor structure (34 items) explaining 56.5% of variance. CFA confirmed the model fit (CFI, RMSEA, etc.). | Cronbach's α: > 0.70Composite Reliability: > 0.70 | Content and face validity were rigorously established via expert panels and target population interviews. |

| Reproductive Health Needs of Violated Women Scale [30] | Women subjected to domestic violence, Iran | Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): Revealed a 4-factor structure (39 items) explaining 47.62% of total variance. | Cronbach's α: 0.94 (total scale)ICC: 0.98 (total scale) | Item generation was informed by a prior qualitative study, ensuring grounding in lived experience. |

| Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Seeking Scale (SRHSSS) [5] | Young adults, Turkey | Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): A 4-factor structure (23 items) was obtained, explaining 89.45% of the variance. | Cronbach's α: 0.90 | The scale development included focus group interviews and expert evaluation to ensure content validity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Validation

Table 3: Key Methodological and Analytical Tools for Construct Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Validation Process | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Expert Panel | To provide evidence for content validity by judging item relevance and representativeness. | Should include methodologies and subject-matter experts (e.g., clinicians, community health experts) [20]. |

| Target Population Sample | To assess face validity, ensure cultural appropriateness, and pilot test the instrument. | Crucial for ensuring questions are understood and relevant to those with lived experience [30]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, SPSS, Mplus) | To perform quantitative psychometric analyses (EFA, CFA, reliability). | R and Mplus offer advanced SEM/CFA capabilities. SPSS is common for EFA and basic reliability analysis. |

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure | To sample adequacy for factor analysis; confirms the data is suitable for EFA/CFA. | Values > 0.8 are desirable; below 0.5 indicates inadequacy [20]. |

| Cronbach's Alpha (α) | To measure the internal consistency reliability of the scale and its subscales. | A necessary but insufficient condition for validity; values of 0.7-0.9 are typically targeted [31] [27]. |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | To quantify test-retest reliability and the stability of measurements over time. | Preferred over simple correlation for continuous data as it accounts for systematic bias [9]. |

Establishing construct validity is an iterative and evidence-driven process that bridges theoretical frameworks with empirical measurement. In reproductive health research, where constructs are complex and measurements have direct implications for clinical care and policy, rigorous validation is not merely methodological but an ethical imperative. By adhering to the sequential workflow—from theoretical definition and content validation through factor analysis and reliability testing—researchers can develop instruments that yield trustworthy and meaningful data. This, in turn, fortifies the scientific foundation upon which advancements in reproductive health outcomes are built.

The development of validated, population-specific assessment tools is a critical component of advancing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) research. Generic health measurement instruments often fail to capture the unique experiences and challenges faced by distinct patient populations, potentially overlooking critical aspects of their health status and quality of life. Within psychometric research, there is growing recognition that condition-specific and population-specific instruments provide more sensitive and clinically relevant measurements [10].

Recent methodological advances have demonstrated the importance of creating tailored instruments for vulnerable populations and those with specific health conditions. The psychometric properties of these tools—including validity, reliability, and sensitivity—are paramount for ensuring they produce scientifically sound data capable of detecting meaningful clinical changes and informing evidence-based interventions [10] [32] [29].

This technical guide examines the development and validation of reproductive health assessment scales across diverse populations, with particular focus on their psychometric properties and methodological considerations for researchers and drug development professionals.

Methodological Framework for Scale Development

The development of robust reproductive health assessment scales typically follows a structured mixed-methods approach that integrates both qualitative and quantitative research phases. The sequential exploratory design has emerged as a particularly effective methodology for this purpose, as implemented in recent studies developing scales for women with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) and HIV-positive women [10] [29].

Core Development Phases

The instrument development process typically progresses through five methodical phases:

- Item Generation: Comprehensive literature review and qualitative studies (interviews, focus groups) to identify relevant concepts and create initial item pools [10] [29]

- Content and Face Validity Assessment: Expert evaluation and participant feedback to refine items for relevance, clarity, and appropriateness [10] [29]

- Pilot Testing and Item Analysis: Administration to a preliminary sample to identify problematic items and assess preliminary psychometric properties [10]

- Construct Validation: Statistical analyses, particularly exploratory factor analysis (EFA), to identify underlying dimensions and scale structure [10] [32] [29]

- Reliability Assessment: Evaluation of internal consistency and test-retest stability [10] [29]

Psychometric Evaluation Metrics

Rigorous psychometric evaluation employs standardized metrics to establish measurement quality. The following table summarizes key psychometric parameters and their acceptable thresholds based on recent scale development studies:

Table 1: Key Psychometric Properties and Standards in Scale Development

| Psychometric Property | Assessment Method | Acceptable Threshold | Exemplary Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content Validity | Content Validity Index (CVI) | ≥0.79 | CVI of 0.926 for SRH-POI scale [10] |

| Content Validity | Content Validity Ratio (CVR) | ≥0.62 (for 10 experts) | CVR based on Lawshe's table [29] |

| Face Validity | Impact Score | ≥1.5 | Qualitative assessment of difficulty, appropriateness, ambiguity [10] |

| Internal Consistency | Cronbach's Alpha | 0.70-0.95 | 0.884 for SRH-POI; 0.713 for HIV-specific scale [10] [29] |

| Test-Retest Reliability | Intraclass Correlation (ICC) | ≥0.70 | ICC of 0.95 for SRH-POI; 0.952 for HIV-specific scale [10] [29] |

| Sampling Adequacy | KMO Measure | ≥0.60 | KMO of 0.83 for SRH-POI factor analysis [10] |

| Construct Validity | Factor Loadings | ≥0.30 | Varimax rotation with loadings >0.3 considered acceptable [29] |

Population-Specific Scale Development: Case Studies

Reproductive Health Scale for Women with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI)

The Sexual and Reproductive Health Assessment Scale for Women with POI (SRH-POI) exemplifies the rigorous development of a condition-specific instrument. POI affects 1-3% of women under 40 and presents significant physical, psychological, and sexual challenges that generic quality-of-life instruments fail to adequately capture [10].

Methodology: The development employed a sequential exploratory mixed-method design between 2019-2021. The initial phase generated an 84-item pool through literature review and qualitative studies. After face and content validity assessment, the pool was reduced to 41 items, with exploratory factor analysis finally yielding a 30-item instrument with a four-factor structure [10].

Psychometric Properties: The scale demonstrated excellent reliability (Cronbach's alpha = 0.884, ICC = 0.95) and strong content validity (S-CVI = 0.926). The factor analysis revealed a coherent structure accounting for significant variance in SRH experiences, with KMO sampling adequacy of 0.83 and Bartlett's test of sphericity confirming sufficient correlation between items for factor analysis [10].

Reproductive Health Assessment for HIV-Positive Women

The reproductive health scale for HIV-positive women addresses the unique challenges faced by this population, including disease-related concerns, life instability, coping with illness, disclosure status, responsible sexual behaviors, and need for self-management support [29].

Methodology: This study also employed an exploratory mixed-methods design with three phases: qualitative data collection through semi-structured interviews and focus groups (n=25), item pool generation, and psychometric evaluation. The initial 48-item pool was refined to a 36-item scale with six factors through content validity assessment and exploratory factor analysis [29].

Psychometric Properties: The instrument demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.713) and excellent test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.952). Content validity was established through both qualitative expert review and quantitative assessment (CVI, CVR) [29].

Mental Health Literacy Scale for Reproductive-Age Women

The Women's Reproductive Ages Mental Health Literacy Scale (WoRA-MHL) represents another application of these methodological principles, focusing on mental health literacy rather than direct health assessment [32].

Methodology: Following a similar mixed-method approach, the final 30-item instrument was organized across four themes: "Accessing and Obtaining Mental Health Information," "Understanding Mental Health Information," "Maintaining Mental Health," and "Adapting to the Challenges of Women's Lives." These factors collectively accounted for 54.42% of the total variance [32].

Psychometric Properties: Confirmatory factor analysis validated a satisfactory model fit, with reliability assessments showing strong internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.889) and excellent test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.966) [32].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Workflows

The development of reproductive health scales follows standardized experimental protocols that ensure scientific rigor and reproducibility. The workflow below visualizes the key stages from conceptualization to final validation.

Diagram 1: Scale Development Workflow

Sample Recruitment and Data Collection Protocols

Robust sampling strategies are essential for developing valid assessment tools. Recent studies have employed various approaches:

- Targeted Sampling: For condition-specific scales (e.g., POI, HIV), participants are typically recruited from clinical settings or specialized patient registries to ensure the sample represents the target population [10] [29].

- Snowball Sampling: For hard-to-reach populations (e.g., refugees), snowball sampling with multiple starting points helps access diverse participants while acknowledging potential limitations in generalizability [33].

- Sample Size Considerations: Appropriate sample sizes are determined through power analysis, with typical participant numbers ranging from 25-50 for qualitative phases to several hundred for quantitative validation [10] [33] [29].

Data collection procedures emphasize standardized administration, private settings for sensitive topics, and trained interviewers who share language and cultural backgrounds with participants when working with vulnerable populations [33].

Quantitative Assessment in Diverse Populations

Specialized Applications in Vulnerable Groups

Assessment tools must be adapted for vulnerable populations with specific accessibility needs. Research with Syrian refugee young women in Lebanon demonstrates approaches to SRH assessment in humanitarian settings [33].

Methodology: A cross-sectional survey of 297 Syrian Arab and Kurdish participants aged 18-30 assessed SRH knowledge and access to services. The questionnaire was developed from validated tools (CDC Reproductive Health Assessment Toolkit, UNFPA Adolescent SRH Toolkit) and administered electronically in Arabic [33].

Findings: The study revealed significant knowledge gaps, with only 49.8% of participants aware of SRH service facilities in their area. Higher education and urban origin were associated with better SRH knowledge. The research developed an unweighted knowledge score assessing STIs, contraceptive methods, and pregnancy danger signs [33].

Advanced Statistical Modeling for Population Health Assessment

Statistical innovation enables estimation of reproductive health indicators when direct measurement is impractical. Recent research has developed modeling approaches for the Demand for Family Planning Satisfied (DFPS) indicator [34].

Methodological Approach: Using survey data from 1,099 subnational regions across 103 countries, researchers fitted least-squares regression models predicting DFPS based on contraceptive prevalence rates. A fractional polynomial approach accounted for non-linear relationships, with model performance evaluated through 5-fold cross-validation [34].

Statistical Models: The analysis produced two primary equations for DFPS by any method (DFPSany) and by modern methods (DFPSm). The models explained over 97% of variability, with minimal bias (approximately 0.1) in cross-validated samples [34].

Table 2: Statistical Models for Family Planning Indicators

| Indicator | Model Equation | Predictors | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFPSany (Demand for Family Planning Satisfied by any method) | ( logit(DFPSany) = 1.05 + (log(CPRany)0.93) + (CPRany^22.49) + (cpdiff*0.70) ) | CPRany, Difference between CPRany and CPRm | >97% |

| DFPSm (Demand for Family Planning Satisfied by modern methods) | ( logit(DFPSm) = 1.12 + (log(CPRm)0.97) + (CPRm^22.13) + (cpdiff*-1.43) ) | CPRm, Difference between CPRany and CPRm | >97% |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

The development and validation of reproductive health assessment scales requires specific methodological components that function as essential "research reagents" in the instrument development process.

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Scale Development

| Component | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) | Identifies underlying factor structure and reduces items to coherent domains | KMO=0.83 and Bartlett's significant test in POI scale [10] |

| Content Validity Index (CVI) | Quantifies expert agreement on item relevance and clarity | S-CVI of 0.926 for SRH-POI scale [10] |

| Content Validity Ratio (CVR) | Assesses essentiality of items based on expert panel evaluation | Lawshe's table minimum CVR of 0.62 for 10 experts [29] |

| Cronbach's Alpha | Measures internal consistency and inter-item correlation | α=0.884 for SRH-POI; α=0.713 for HIV-specific scale [10] [29] |

| Intraclass Correlation (ICC) | Evaluates test-retest reliability and temporal stability | ICC=0.95 for SRH-POI over 2-week interval [10] |

| Impact Score | Assesses item clarity and importance from participant perspective | Score ≥1.5 considered acceptable for item retention [10] |

| Varimax Rotation | Simplifies factor structure by maximizing variance of loadings | Orthogonal rotation with factor loadings >0.3 [29] |

The development of population-specific reproductive health assessment scales represents a methodological advancement in health services research and clinical trial design. The rigorous psychometric frameworks demonstrated across these case studies provide researchers with validated protocols for creating sensitive, reliable measurement tools.

The consistent finding across all studies is that condition-specific and population-specific instruments capture unique aspects of health experiences that generic tools miss. The strong psychometric properties of these scales—including high reliability coefficients, robust factor structures, and excellent content validity—support their utility in both clinical research and intervention evaluation.

Future directions in this field include cross-cultural validation of existing instruments, development of computerized adaptive testing versions to reduce respondent burden, and integration of these scales as endpoints in clinical trials of therapeutic interventions for reproductive health conditions.

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to Scale Development and Deployment

Item generation is the foundational phase in creating a valid and reliable psychometric instrument. It involves the systematic creation of a comprehensive pool of questionnaire items that represent the entire theoretical domain of the construct being measured [35]. In reproductive health survey research, this process ensures the assessment tool adequately captures the multifaceted nature of sexual and reproductive health experiences, behaviors, and attitudes. The quality of this initial phase directly impacts all subsequent psychometric evaluations, including validity and reliability testing [10]. Without a robust item generation process, even sophisticated statistical analyses cannot compensate for content gaps or conceptual misalignment in the final instrument.

Within the broader context of psychometric property evaluation, item generation establishes the content validity foundation upon which other measurement properties (construct validity, criterion validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability) are later built [35] [36]. For reproductive health research specifically, this process must account for culturally sensitive topics, diverse population needs, and complex behavioral determinants that influence health outcomes [37] [38].

Methodological Approaches to Item Generation

Comprehensive Literature Review

A systematic literature review forms the scholarly foundation for item generation by identifying established constructs, measurement gaps, and existing terminology relevant to the target domain.

Protocol Implementation:

- Search Strategy Development: Define comprehensive search terms encompassing relevant reproductive health concepts (e.g., "reproductive autonomy," "contraceptive access," "sexual health communication") across multiple databases [10]. The SRH-POI scale development team searched SID, Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, and other databases spanning publications from 1950 to 2021 [10].

- Existing Instrument Analysis: Identify and evaluate previously developed instruments for potentially adaptable items while ensuring copyright compliance. For the Reproductive Autonomy Scale (RAS) adaptation in the UK, researchers analyzed the original US scale to maintain conceptual equivalence while ensuring cultural appropriateness [9].

- Conceptual Mapping: Synthesize findings into a conceptual framework that identifies core domains and subdomains of the construct. The SRH-POI scale development identified multiple dimensions through literature review before qualitative investigation [10].

Table 1: Literature Review Documentation Protocol

| Review Component | Documentation Element | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Search Parameters | Databases searched, date ranges, search terms | PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science (2010-2025) |

| Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Systematic criteria for source selection | Peer-reviewed articles, validated instruments, specific populations |

| Extracted Concepts | Thematic organization of findings | Reproductive decision-making, service access barriers, communication autonomy |

| Existing Items | Catalog of adaptable questionnaire items | 84-item pool generated for SRH-POI scale [10] |

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research provides the lived-experience context that literature alone cannot capture, ensuring the item pool reflects the actual concerns, language, and conceptual frameworks of the target population.

Protocol Implementation:

- Participant Recruitment: Employ purposive sampling to ensure diverse representation across relevant demographics (age, socioeconomic status, geographic location, reproductive experiences) [38]. In a study exploring SRH service use in Ethiopia, researchers selected participants based on "age, educational level, and relationship status" to capture varied perspectives [38].

- Data Collection Techniques: Implement semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, or observational methods to explore the construct domain. The DHS Program utilizes "focus group discussions, in-depth interviews, and personal narratives" to understand social and cultural contexts of reproductive health [39].

- Thematic Analysis: Employ systematic coding procedures to identify emergent themes and concepts using established qualitative methodology. Braun and Clarke's thematic analysis framework has been applied in reproductive health literature reviews to identify key themes across studies [37].

Implementation Considerations:

- Saturation Principle: Continue data collection until no new themes emerge from subsequent interviews or focus groups. In the Ethiopian SRH study, researchers used "data saturation" to determine when sufficient interviews had been conducted [38].

- Stakeholder Inclusion: Engage multiple perspectives, including healthcare providers and diverse patient populations, to capture comprehensive conceptualization. A study in Ethiopia included both adolescents (service users) and health professionals (service providers) to understand SRH service use from multiple angles [38].

Integration and Initial Item Pool Development

The integration phase synthesizes findings from both literature review and qualitative research to create a comprehensive preliminary item pool.

Concept Synthesis and Domain Specification

Systematically map identified concepts from both sources into coherent domains and subdomains that collectively represent the entire construct space. The Reproductive Autonomy Scale was structured around a confirmed "three-factor structure" identified through this synthetic process [9].

Protocol Implementation:

- Conceptual Matrix Development: Create a cross-walking framework that aligns literature-derived constructs with qualitative themes to identify coverage gaps and redundancies.

- Domain Specification: Define clear operational definitions for each domain to guide item creation. Reproductive health research often identifies domains such as "contraceptive use, childbearing preferences, and healthcare decision-making" [9].

- Item Conceptualization: Develop items that precisely map to each domain while using language and conceptual frameworks identified in qualitative research.

Table 2: Integration Framework for Reproductive Health Constructs

| Domain Identified | Literature Support | Qualitative Validation | Sample Item Stem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contraceptive Decision-Making | Previous scales measuring reproductive autonomy [9] | Young women's reported experiences with provider interactions [38] | "I decide what contraceptive method to use..." |

| Healthcare Access Barriers | Documented structural barriers in marginalized populations [37] | Experiences of stigma and discrimination reported in interviews [38] | "I can get reproductive healthcare when..." |

| Relationship Communication | Sexual Assertiveness Scale items [9] | Partner dynamics described in focus groups [39] | "I feel comfortable discussing contraception with my partner..." |

| Service Provider Interactions | Power dynamics in clinical settings [9] | Youth reports of judgmental provider attitudes [38] | "My healthcare provider listens to my concerns about..." |

Item Formulation and Documentation

Transform identified concepts into preliminary questionnaire items using established item-writing principles to minimize bias and enhance comprehension.

Protocol Implementation:

- Item Writing: Develop clear, unambiguous items using appropriate response formats (e.g., Likert scales, frequency scales, binary responses). The SRH-POI scale used a "5-part Likert scale" for response options [10].

- Language Appropriation: Utilize terminology and phrasing identified during qualitative research to enhance cultural and contextual relevance. Research with underserved groups highlights the importance of using "accessible language" that reflects how participants conceptualize their experiences [37].

- Comprehensive Documentation: Maintain detailed records of each item's conceptual origin, development rationale, and corresponding domain.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Qualitative Item Generation

| Research 'Reagent' | Function in Item Generation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | Ensure systematic exploration of domain-relevant topics while allowing emergent themes | Guides with open-ended questions about reproductive healthcare experiences [38] |

| Focus Group Protocols | Facilitate group interaction to identify shared conceptual frameworks and terminology | Discussions exploring community norms around contraceptive use [39] |

| Digital Recorders & Transcription Services | Create verbatim records of qualitative data for systematic analysis | Audio recording of interviews with adolescents about SRH services [38] |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software | Facilitite systematic coding and thematic analysis (e.g., NVivo, MAXQDA) | Software used to identify emergent themes across multiple interviews [37] |

| Conceptual Mapping Tools | Visualize relationships between concepts and domains during analysis | Diagrams linking themes like "stigma," "access," and "autonomy" in reproductive health |

| Systematic Review Databases | Identify established constructs and existing measures | PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO searches for reproductive autonomy measures [9] [10] |

Quality Assurance in Item Generation

Implement systematic quality checks throughout the item generation process to ensure comprehensive content coverage and minimal construct-irrelevant variance.

Protocol Implementation:

- Expert Consultation: Engage content experts and methodological specialists to review the conceptual framework and item-domain alignment. The SRH-POI scale development involved asking "10 researchers and reproductive health experts" to provide input on the preliminary tool [10].

- Pilot Cognitive Testing: Conduct preliminary testing with target population members to assess item comprehensibility, sensitivity, and relevance. This process helps identify terminology that may be misunderstood or culturally inappropriate.

- Documentation Audit: Verify thorough documentation of all methodological decisions and item rationales to create an audit trail for subsequent validation phases.

The item generation phase culminates in a comprehensive item pool ready for formal content validation, where items undergo systematic evaluation by stakeholders and experts for relevance, comprehensiveness, and appropriateness before proceeding to quantitative psychometric evaluation. This rigorous approach to initial scale development establishes the foundation for instruments with strong content validity, enabling accurate measurement of complex reproductive health constructs across diverse populations [9] [10].

In the development of reproductive health surveys, establishing robust psychometric properties is paramount to ensuring that research data is valid, reliable, and actionable. Within this framework, content and face validity represent foundational validation stages that determine whether an instrument adequately measures the constructs it purports to measure. Content validity assesses the degree to which a scale's items comprehensively represent the target domain, while face validity evaluates whether the items appear appropriate to end users. For reproductive health research—where constructs like empowerment, coercion, and health behaviors are complex and multidimensional—these validation phases require systematic methodological approaches employing expert panels to leverage collective scientific judgment [40] [41].

The rigorous development of reproductive health scales, such as the Reproductive Autonomy Scale [9], the Reproductive Coercion Scale [41], and the Sexual and Reproductive Health Assessment Scale for women with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency [10], demonstrates that structured validity assessment is critical for producing instruments that yield scientifically sound results. This technical guide provides researchers with comprehensive methodologies for establishing content and face validity through expert panels, framed within the broader context of psychometric validation for reproductive health surveys.