Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs): Exposure Routes, Health Impacts, and Risk Assessment Strategies for Biomedical Research

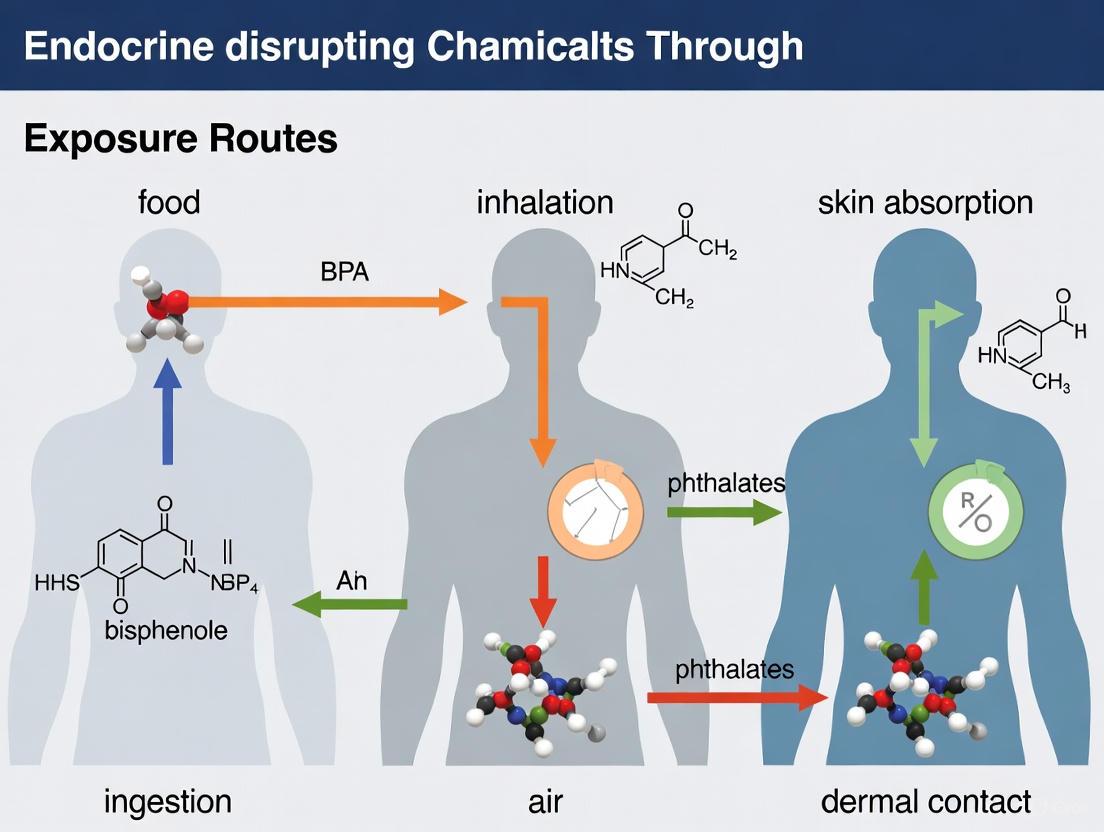

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical (EDC) exposure routes—food, air, and skin absorption—and their implications for human health and drug development.

Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs): Exposure Routes, Health Impacts, and Risk Assessment Strategies for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical (EDC) exposure routes—food, air, and skin absorption—and their implications for human health and drug development. It synthesizes foundational knowledge on EDC mechanisms and sources, explores advanced methodologies for exposure assessment and biomonitoring, addresses challenges in risk evaluation and mitigation, and examines validation frameworks and regulatory landscapes. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review consolidates current evidence to inform robust study design, risk assessment, and public health policy.

Understanding EDCs: Sources, Exposure Routes, and Mechanistic Pathways to Disease

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are defined as exogenous (non-natural) chemicals, or mixtures of chemicals, that can interfere with any aspect of hormone action [1]. The endocrine system, which includes glands distributed throughout the body that produce hormones, controls critical biological processes such as normal growth, fertility, and reproduction [2]. These hormones act as signaling molecules in extremely small amounts, and even minor disruptions in their levels may cause significant developmental and biological effects [2]. EDCs include a wide array of natural and human-made substances found in pesticides, cosmetics, household cleaners, plastic containers, food packaging, fabric, upholstery, electronics, and medical equipment [3].

The global scientific community has recognized EDCs as emerging contaminants and a significant public health challenge [3]. These chemicals contaminate nearly every ecosystem tested, even in the most remote areas of the world, and are significantly associated with various neurological, neurodevelopmental, and reproductive disorders [3]. Research activity on EDCs has increased disproportionately, with a strong north-south divide in publication performance, dominated by the United States and China [3]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the mechanisms through which EDCs interfere with the endocrine system, the primary routes of human exposure, and the resulting health effects, with particular focus on food, air, and skin absorption pathways.

Mechanisms of Endocrine Disruption

Key Characteristics of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals

Informed by the consensus of international experts, EDCs can be systematically identified and evaluated based on ten key characteristics (KCs) that reflect their ability to interfere with hormone systems [4]. These KCs provide a framework for organizing mechanistic evidence and reflect current scientific knowledge of hormone action [4].

Table 1: Ten Key Characteristics of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals

| Characteristic | Mechanism of Action | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| KC1: Interacts with or activates hormone receptors | EDCs inappropriately bind to and/or activate hormone receptors, mimicking natural hormones | DDT binds to estrogen receptors (ERα/ERβ); hydroxylated PCBs activate thyroid hormone receptor-β [4] |

| KC2: Antagonizes hormone receptors | EDCs inhibit or block effects of endogenous hormones by acting as receptor antagonists | Organochlorine pesticides inhibit androgen binding to the androgen receptor [4] |

| KC3: Alters hormone receptor expression | EDCs modulate hormone receptor expression, internalization, and degradation | BPA alters expression of estrogen, oxytocin, and vasopressin receptors in brain nuclei [4] |

| KC4: Alters signal transduction in hormone-responsive cells | EDCs disrupt intracellular responses triggered by hormone-receptor binding | BPA blocks glucose-induced calcium signaling in pancreatic α-cells [4] |

| KC5: Induces epigenetic modifications in hormone-producing or responsive cells | EDCs cause heritable changes in gene expression without altering DNA sequence | Diethylstilbestrol (DES) causes epigenetic changes in reproductive organs of mice [2] [4] |

| KC6: Alters hormone synthesis | EDCs affect production and secretion of hormones | Perchlorate inhibits thyroidal iodide uptake and thyroid hormone synthesis [4] |

| KC7: Alters hormone transport across cell membranes | EDCs disrupt circulating hormone transport proteins | PBDEs compete with thyroid hormone for binding to transthyretin [4] |

| KC8: Alters hormone distribution or circulating levels | EDCs modify hormone metabolism and clearance | PCBs increase metabolism and clearance of thyroid hormones [4] |

| KC9: Alters fate of hormone-producing or responsive cells | EDCs affect proliferation, differentiation, or death of hormone-sensitive cells | Phthalates alter germ cell numbers and reproductive tract development [4] |

| KC10: Alters hormone-regulated physiological systems | EDCs interfere with homeostasis, reproduction, development, and/or behavior | EDC mixtures alter brain pathways controlling reward preference and eating behavior [5] |

Molecular Pathways of Endocrine Disruption

The following diagram illustrates the primary molecular pathways through which EDCs interfere with normal endocrine signaling, from cellular reception to systemic physiological effects:

EDCs employ multiple mechanisms to disrupt endocrine function, often simultaneously. They can mimic natural hormones, block hormone receptors, or alter hormone production, transport, and metabolism [6]. The mechanisms are particularly consequential during sensitive developmental windows, such as embryonic development, pregnancy, and lactation, when small disturbances in endocrine function can lead to profound and lasting effects [6].

Exposure Routes and Environmental Vectors

Primary Exposure Pathways

Human exposure to EDCs occurs through three primary routes: diet, inhalation, and dermal absorption [1]. The following diagram illustrates the major exposure pathways and their connections to common EDC sources:

Dietary ingestion represents a major exposure route for numerous EDCs. Chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA) leach from food and beverage packaging, while pesticides like atrazine and other agricultural chemicals contaminate food products [2]. Phthalates, used as liquid plasticizers, can migrate from food packaging into contents [2]. Perchlorate, an industrial chemical used in rockets, explosives, and fireworks, has been detected in some groundwater sources and can enter the food chain [2]. Dioxins, generated as byproducts of manufacturing processes and waste burning, accumulate in the food chain, particularly in animal fats [2].

Dermal absorption occurs through direct contact with personal care products, cosmetics, and household items containing EDCs. Phthalates are found in hundreds of products including cosmetics, fragrances, nail polish, hair spray, and shampoos [2]. The skin, being the main route of exposure for cosmetic products, can absorb these chemicals, especially when the skin's protective barrier is compromised [7]. An individual typically uses at least two personal care products in a 24-hour period, with between 30-40% of dermatologist prescriptions containing at least one personal care product component [1].

Inhalation exposes individuals to EDCs through airborne contaminants. Chemicals from personal care products, such as siloxanes and phthalates, can become airborne and contaminate indoor air [1]. For instance, shower gel and shampoo alone can emit significant quantities of siloxanes per individual per day [1]. Dioxins released into the air from waste burning and wildfires represent another inhalation exposure source [2]. Household dust also serves as a reservoir for EDCs like flame retardants (PBDEs) that can become airborne and inhaled [2].

Table 2: Major Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Exposure Sources

| EDC Category | Common Sources | Primary Exposure Routes |

|---|---|---|

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Polycarbonate plastics, epoxy resins, food can linings, toys, thermal paper receipts | Dietary ingestion (primary), dermal absorption [2] [1] |

| Phthalates | Food packaging, cosmetics, fragrances, children's toys, medical device tubing, personal care products | Dermal absorption, dietary ingestion, inhalation [2] [1] |

| Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) | Firefighting foam, nonstick pans, paper and textile coatings, food packaging | Dietary ingestion, inhalation of household dust [2] |

| Pesticides | Agricultural applications (atrazine, DDT, glyphosate), home and garden products, contaminated food and water | Dietary ingestion, inhalation, dermal absorption [2] [8] |

| Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) | Electrical equipment, hydraulic fluids, plasticizers (despite 1979 ban, persistent in environment) | Dietary ingestion (especially fish), inhalation [2] |

| Dioxins | Industrial processes, waste incineration, wildfires, herbicide production | Dietary ingestion (animal fats), inhalation [2] |

| Phytoestrogens | Naturally occurring in plants (soy foods, flaxseeds) | Dietary ingestion [2] |

| Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) | Flame retardants in furniture foam, carpet, electronics | Inhalation of household dust, dietary ingestion [2] |

| Heavy Metals | Industrial processes, contaminated water and soil, certain foods | Dietary ingestion, inhalation [8] |

| Triclosan | Previously in antimicrobial soaps and personal care products (restricted in some regions) | Dermal absorption, inhalation [2] |

Health Effects and Associated Outcomes

Comprehensive Health Impact Analysis

An umbrella review of 67 meta-analyses encompassing 109 health outcomes from 7,552 unique articles revealed significant associations between EDC exposure and numerous adverse health conditions [8]. The analysis included pesticides (30 studies), BPA (13 studies), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAHs (18 studies), PFAS (10 studies), and heavy metals (38 studies) [8].

Table 3: Health Outcomes Associated with EDC Exposure

| Health Category | Specific Outcomes with Significant Associations | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 22 cancer outcomes including breast, prostate, testicular, and reproductive cancers | Strong evidence from multiple meta-analyses [8] |

| Reproductive Health | Infertility, endometriosis, decreased sperm quality, PCOS, premature thelarche, reproductive tract malformations | Strong consistent evidence across studies [2] [1] [6] |

| Metabolic Disorders | Obesity, diabetes, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome | Significant associations with 18 metabolic disorder outcomes [8] |

| Neurodevelopment | ADHD, cognitive deficits, neurodevelopmental delays, autism spectrum behaviors | Strong evidence, particularly for prenatal exposures [2] [3] |

| Cardiovascular Health | Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis | 17 significant cardiovascular disease outcomes [8] |

| Pregnancy & Fetal Development | Preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, implantation failure, gestational diabetes | 11 significant pregnancy-related outcomes [8] |

| Immune Function | Diminished immune response to vaccines, immune system dysfunction | Children exposed to high PFAS levels showed reduced vaccine response [2] |

| Other Systems | Renal, respiratory, and hematologic outcomes | 20 additional significant outcomes across various systems [8] |

Developmental and Transgenerational Effects

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of EDC exposure involves their impact during critical developmental windows. The developing fetus is particularly vulnerable to EDCs, which can cross the placental barrier and interfere with organ formation and differentiation [3] [6]. Exposure during these sensitive periods can lead to epigenetic changes that alter gene expression patterns and increase disease susceptibility later in life [2] [4].

The case of diethylstilbestrol (DES) exemplifies the devastating consequences of developmental EDC exposure. From the 1940s through 1970s, DES was prescribed to pregnant women to prevent miscarriage, but was later linked to vaginal cancer in daughters of women who took the drug, along with numerous noncancerous changes in both sons and daughters [2]. This experience demonstrated that EDC exposure during development can cause long-lasting health effects that manifest decades later, sometimes even in subsequent generations [2].

Recent research continues to reveal transgenerational effects of EDCs. Animal studies have shown that exposure to EDCs during gestation can lead to epigenetic transgenerational actions affecting mate fertility in subsequent generations [3]. Additionally, early-life exposure to EDCs has been linked to altered food preferences and reward pathways in the brain, potentially contributing to obesity rates [5]. University of Texas researchers found that rats exposed to EDC mixtures during gestation or infancy showed heightened preference for sugary and fatty foods later in life, with physical changes in brain regions controlling food intake and reward response [5].

Experimental Methodologies and Research Approaches

Research Workflow for EDC Hazard Assessment

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for identifying and characterizing endocrine-disrupting chemicals:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

In Vitro Receptor Binding Assays Protocol Objective: To determine the ability of test chemicals to bind to and activate or inhibit hormone receptors including estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), androgen receptor (AR), and thyroid hormone receptors (TRα and TRβ).

Methodology:

- Receptor Preparation: Isolate and purify recombinant human hormone receptors or use receptor-containing cell lines (e.g., MCF-7 cells for ER, HEK293 cells transfected with AR).

- Competitive Binding Assay: Incubate receptors with radiolabeled natural hormones (³H-estradiol for ER, ³H-testosterone for AR) in the presence of increasing concentrations of test chemicals.

- Separation and Measurement: Separate bound from free ligand using charcoal adsorption, filtration, or immunoprecipitation methods.

- Data Analysis: Calculate IC₅₀ values and relative binding affinity (RBA) compared to natural hormones. RBA = (IC₅₀ of reference compound/IC₅₀ of test compound) × 100.

Quality Control: Include reference EDCs (DES for ER, vinclozolin for AR) as positive controls and vehicle-only as negative control. Perform experiments in triplicate with at least three independent replicates [4].

Transcriptional Activation Assays Protocol Objective: To assess the ability of test chemicals to activate hormone-responsive gene expression.

Methodology:

- Reporter Gene Construction: Transfect cells with plasmid containing hormone response elements (ERE for estrogen, ARE for androgen) upstream of a luciferase or GFP reporter gene.

- Chemical Exposure: Expose transfected cells to a range of test chemical concentrations (typically 10⁻¹² to 10⁻⁶ M) for 24-48 hours.

- Response Measurement: Lyse cells and measure reporter gene activity using luminometry (luciferase) or fluorometry (GFP).

- Dose-Response Analysis: Calculate EC₅₀ values and efficacy relative to natural hormones.

Variations: Yeast-based reporter systems provide alternative screening platform with different permeability and metabolic properties [4].

In Vivo Pubertal Assay (EPA OPPTS 890.1450) Protocol Objective: To detect endocrine-disrupting effects on pubertal development and thyroid function.

Methodology:

- Animal Model: Weanling rats (Sprague-Dawley, Wistar, or Long-Evans) at postnatal day 21.

- Exposure Regimen: Administer test chemical orally (by gavage) or in diet for 21-31 days.

- Endpoints Measured:

- Vaginal opening (females) and preputial separation (males) as puberty markers

- Estrous cyclicity (females)

- Thyroid histopathology

- Serum T₃, T₄, and TSH levels

- Organ weights (liver, kidney, pituitary, thyroid, reproductive organs)

- Statistical Analysis: Compare treatment groups to controls using ANOVA followed by appropriate post-hoc tests.

Interpretation: Delayed or accelerated puberty suggests sex steroid-mediated effects; thyroid histopathology and hormone changes indicate thyroid disruption [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for EDC Investigation

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Specific Utility in EDC Research |

|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 cells | Estrogen receptor binding and proliferation assays | Human breast cancer cell line expressing ERα; used to assess estrogenic activity via proliferation (E-SCREEN) and gene expression changes [4] |

| MDA-kb2 cells | Androgen and glucocorticoid receptor screening | Stably transfected with MMTV-luciferase reporter; responsive to androgens and glucocorticoids for screening antagonist/agonist activity [4] |

| GH3 cells | Thyroid hormone disruption assessment | Rat pituitary cell line that proliferates in response to thyroid hormone disruption; used to detect thyroid receptor-mediated effects [4] |

| Recombinant ERα, ERβ, AR | Receptor binding assays | Purified human receptors for high-throughput screening of chemical binding affinity and competitive displacement of natural hormones [4] |

| Yeast Reporter Systems | Transcriptional activation screening | Genetically engineered yeast expressing human hormone receptors and reporter genes; provides cost-effective high-throughput screening [4] |

| ER-EcoScreen | Rapid estrogenicity screening | Chinese hamster ovary cells stably transfected with human ERα and estrogen-responsive luciferase reporter; optimized for sensitivity and throughput [4] |

| Radiolabeled Ligands (³H-estradiol, ³H-testosterone) | Competitive binding assays | High-specific-activity radioligands for precise measurement of receptor binding affinity and kinetics [4] |

| Transthyretin Binding Assay | Thyroid hormone transport disruption | Assesses chemical competition with thyroid hormones for binding to transport proteins; critical for identifying TH disruption mechanisms [4] |

Regulatory Framework and Testing Guidelines

The regulatory landscape for EDCs has evolved significantly, with various international approaches to hazard identification and risk management. In the European Union, criteria for identifying EDCs are established in regulations for biocides (2100/2017), plant protection products (2018/605), and the REACH Regulation [7]. These regulations stipulate that substances posing endocrine disruption risks should not be placed on the market, reflecting the precautionary principle that is fundamental to EU risk governance [7].

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has established an endocrine disruptor screening program as mandated by Congress, representing a significant step in improving evaluation and regulation of chemicals with endocrine-disrupting properties [6]. This program employs a two-tiered approach:

Tier 1 Screening:

- Assays to detect interaction with estrogen, androgen, and thyroid systems

- Includes in vitro and short-term in vivo screens

- Designed to identify potential for endocrine activity

Tier 2 Testing:

- Longer-term in vivo studies

- Assesses adverse effects and dose-response relationships

- Focuses on development, reproduction, and growth

The complexity of risk regulation in this field stems from scientific uncertainty, variability in testing methodologies, and challenges in extrapolating from experimental models to human health outcomes [7]. Current research efforts focus on developing new models and tools to better understand how endocrine disruptors work, applying high-throughput assays to identify substances with endocrine-disrupting activity, and identifying new intervention and prevention strategies [2].

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals represent a significant challenge to public health due to their ubiquitous presence in the environment and ability to interfere with hormonal signaling at extremely low concentrations. Understanding the mechanisms of endocrine disruption—from molecular interactions with hormone receptors to systemic health effects—provides the foundation for developing effective regulatory policies and protective measures.

The ten key characteristics of EDCs offer a systematic framework for identifying and evaluating these chemicals, while advancing testing methodologies continue to improve our ability to detect endocrine-disrupting activity. Given the widespread exposure to EDCs through multiple routes including food, air, and dermal absorption, and the growing evidence linking them to serious health outcomes across life stages, continued research and precautionary approaches to chemical management are warranted to reduce population-level exposure and mitigate potential health risks.

Environmental endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a diverse class of exogenous compounds that interfere with hormonal signaling pathways, posing significant threats to human health. The mechanisms by which these compounds exert their effects are intrinsically linked to their routes of entry into the human body. Understanding the primary exposure triad—ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption—is fundamental for researchers, toxicologists, and public health professionals working to assess and mitigate health risks. Exposure to EDCs is widespread and continuous, occurring through multiple pathways simultaneously, which complicates risk assessment and necessitates a thorough understanding of exposure dynamics [9] [10]. This whitepaper synthesizes current scientific evidence on these exposure routes, providing a technical foundation for exposure assessment in research and regulatory contexts.

The concept of "pseudo-persistence" is particularly relevant when considering exposure routes, wherein chemicals that are not inherently persistent in the environment nonetheless maintain a constant presence in human tissues due to continuous exposure from multiple sources and pathways [11]. This phenomenon underscores the importance of evaluating not just the chemical properties of EDCs, but also the human behaviors and environmental contexts that facilitate exposure. With over 85,000 intentionally synthesized chemicals in commerce, and numerous others formed as unintentional byproducts, systematic approaches to exposure science are urgently needed [11].

Defining the Exposure Triad

The human body interfaces with EDCs primarily through three major pathways: ingestion via the gastrointestinal tract, inhalation through the respiratory system, and dermal absorption via the skin. Each route possesses distinct anatomical and physiological characteristics that influence the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of EDCs. Ingestion represents a major exposure route for EDCs found in food, water, and through hand-to-mouth transfer of contaminated dust [9]. Inhalation introduces airborne EDCs directly into the respiratory system, where they can access the bloodstream or exert local effects in lung tissue [12]. Dermal absorption allows chemicals to penetrate the skin's layers from personal care products, textiles, or environmental media [13].

Real-world exposure scenarios typically involve complex mixtures of EDCs entering through multiple routes simultaneously, creating aggregate exposure that challenges traditional risk assessment paradigms. The timing, duration, and concentration of exposure interact with individual susceptibility factors such as age, genetics, and health status to determine ultimate health outcomes. Critical windows of development—including fetal development, infancy, and puberty—represent periods of heightened susceptibility to EDC exposure through all routes [10] [9].

Table 1: Characteristics of Primary EDC Exposure Routes

| Exposure Route | Primary Sources | Structural Features Enabling Exposure | Key Determinants of Absorption Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ingestion | Contaminated food and water, food packaging, hand-to-mouth transfer | High lipid solubility, resistance to digestive enzymes | Gastrointestinal pH, gut microbiota, fat content of food |

| Inhalation | Airborne particles, volatile compounds, dust | Low molecular weight, volatility | Particle size, respiratory rate, alveolar surface area |

| Dermal Absorption | Personal care products, textiles, industrial chemicals | Low molecular weight (<500 Da), lipophilicity | Skin integrity, hydration, vehicle/formulation |

Ingestion as a Primary Exposure Route

The ingestion route constitutes a major pathway for EDC exposure, with dietary intake representing a significant source for many populations. EDCs enter the food chain through multiple mechanisms, including bioaccumulation in animal fats, contamination of agricultural products, and migration from food packaging materials [14]. Plastic monomers and additives such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates are particularly concerning due to their propensity to leach from food containers and packaging into food contents, especially under conditions of heat or prolonged contact [14] [10]. Typical daily intake levels have been documented at 0.1-4 µg/kg body weight for BPA and 1-20 µg/kg body weight for phthalates [14].

Heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants (POPs) also frequently enter the body via ingestion. Cadmium and lead demonstrate exceptional environmental persistence with biological half-lives extending 20-30 years in human tissues, primarily accumulating through contaminated drinking water and food chain bioaccumulation [14]. POPs, including dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), exhibit exceptional chemical stability allowing environmental persistence exceeding two decades, leading to progressive bioaccumulation through food webs and preferential storage in lipid-rich tissues [14].

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Biomonitoring approaches for assessing ingestion exposure typically involve analysis of EDCs and their metabolites in biological matrices, with urine and blood being the most common. For biomonitoring of phthalate exposure, researchers typically collect spot urine samples and measure concentrations of monoester metabolites using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). These measurements are often corrected for urinary dilution using creatinine adjustment [9]. For lipophilic compounds that accumulate in adipose tissue, such as PCBs and organochlorine pesticides, serum lipid analysis provides a more appropriate exposure metric than urinary measurements [14].

Dietary exposure assessment often employs duplicate diet studies, where participants consume duplicates of all foods and beverages consumed during a specified period, with subsequent chemical analysis of the composite samples. Migration studies for food contact materials typically involve simulating real-world use conditions by exposing food simulants (e.g., water, 10% ethanol, 3% acetic acid, or olive oil) to packaging materials under controlled time-temperature conditions, followed by chemical analysis of the simulants to quantify leaching [14].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Assessing Ingestion Exposure to EDCs

| Methodology | Key Applications | Analytical Techniques | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomonitoring | Quantifying internal dose from all exposure routes | HPLC-MS/MS, GC-MS | Measures integrated exposure from all sources | Cannot distinguish exposure routes |

| Duplicate Diet Study | Dietary exposure assessment | GC-MS, HPLC-MS/MS | Direct measurement of dietary exposure | Labor-intensive, expensive |

| Migration Testing | Leaching from food contact materials | HPLC-MS/MS, GC-MS | Controlled conditions, reproducible | May not fully replicate real-use conditions |

| Market Basket Survey | Population dietary exposure estimation | GC-MS, HPLC-MS/MS | Representative of food supply | Does not account for individual consumption patterns |

Inhalation Exposure Pathways

Airborne EDCs and Respiratory Uptake

Inhalation exposure to EDCs occurs through airborne particles, volatile organic compounds, and semi-volatile compounds that partition to dust particles. Phthalates, which are commonly used as plasticizers, demonstrate significant inhalation exposure potential due to their presence in indoor air and dust [12]. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that phthalates in dust samples were significantly associated with asthma onset in children and adolescents (OR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.02-1.44) [12]. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) used as flame retardants exhibit remarkable biological persistence, with half-lives extending 3-7 years and high octanol-water partition coefficients (log Kow = 6.5-8.4), facilitating extensive bioaccumulation through inhalation of household dust [14].

Recent research has expanded to include respiratory health outcomes beyond asthma. A 2025 study analyzing NHANES data revealed that exposure to EDC mixtures was associated with preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm), a precursor to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [15]. Weighted quantile sum regression demonstrated that each index rise in the EDC-mixture increased the odds of PRISm by 63% (OR=1.63, 95% CI: 1.25-2.13), with mono-isobutyl phthalate (MIBP) identified as a primary driver of this effect (OR=2.29, 95% CI: 1.71-3.07) [15].

Methodologies for Air Sampling and Analysis

Assessment of inhalation exposure requires specialized air sampling techniques that vary based on the physical-chemical properties of target EDCs. For semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) like phthalates and PBDEs, settled dust sampling is commonly employed using standardized vacuum sampling protocols with predetermined sampling areas and nozzle sizes [12]. Dust samples are typically sieved to a specific particle size (e.g., <100 μm) before extraction and analysis via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

Active air sampling methods utilize pumps to draw air through collection media, such as polyurethane foam (PUF) plugs for volatile compounds or quartz fiber filters for particle-bound compounds. These approaches allow for determination of airborne concentrations but require specialized equipment and may not capture temporal variability in exposure. Passive air samplers, including PUF passive samplers or silicone wristbands, provide time-integrated measurements that can be deployed in personal exposure assessment studies [12].

Dermal Absorption Mechanisms

Skin Penetration Dynamics

Dermal absorption constitutes a significant exposure pathway for EDCs present in personal care products, cosmetics, and textiles. The skin's structure presents a complex barrier with the stratum corneum serving as the primary rate-limiting layer for chemical penetration. Key chemical properties influencing dermal absorption include molecular weight (with compounds <500 Da penetrating more readily), lipophilicity (optimal log Kow 1-3), and hydrogen bonding potential [16]. The dermal route is particularly relevant for EDCs such as phthalates, parabens, triclosan, and ultraviolet filters found in cosmetics and personal care products.

A 2025 systematic review of cosmetic ingredients identified 27 chemicals categorized as having "indications for ED properties" out of 890 cosmetic ingredients reviewed, highlighting the prevalence of potential EDCs in products that directly contact skin [16]. The study developed a workflow to screen cosmetic ingredients against known EDC lists from regulatory agencies and scientific sources, providing a methodology for prioritizing chemicals for further safety assessment. For one of these chemicals, geraniol, aggregate exposure was modeled using PACEMweb software and compared to the lowest observed adverse effect level from toxicological studies, demonstrating an approach for evaluating endocrine-related health risks from dermal exposure [16].

Experimental Models for Dermal Absorption

In vitro dermal absorption testing typically employs human or animal skin membranes mounted in Franz diffusion cells, which maintain physiological temperature and humidity conditions. The skin membrane separates a donor chamber (containing the test material) from a receptor chamber (containing collection fluid), allowing quantification of chemical permeation over time [16]. Excised human skin from surgical procedures represents the gold standard, while reconstructed human skin models (e.g., EpiDerm, EpiSkin) offer alternatives that avoid animal use.

In vivo studies, while less common due to ethical concerns and regulatory restrictions, provide important validation data for in vitro models. Human volunteer studies sometimes use topical application of stable isotope-labeled EDCs to distinguish applied chemicals from background exposure, with subsequent measurement of metabolites in urine or blood to determine systemic absorption [16]. Alternative approaches include the use of silicone wristbands or other passive samplers worn on the skin to assess potential dermal exposure, though these measure available concentration rather than actual absorption [13].

Integrated Exposure Assessment and Research Gaps

Aggregate Exposure Assessment

Comprehensive EDC risk assessment requires integration of exposure across all three routes—ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption—to determine total body burden. Aggregate exposure assessment presents substantial methodological challenges due to differences in measurement approaches, timing of exposure, and metabolic fate across routes. Biomonitoring data, which measure the internal concentration of EDCs or their metabolites, provide integrated measures of exposure from all routes but cannot distinguish the contribution of each pathway [17].

Computational approaches for aggregate exposure assessment include probabilistic models that combine exposure factors, such as those implemented in the PACEMweb software used for cosmetic safety assessment [16]. These models integrate product composition data, usage patterns, and absorption parameters to estimate total systemic exposure. For EDCs with multiple exposure sources, such as phthalates, studies have demonstrated that exposure routes can be complementary, with no single source dominating total exposure, necessitating comprehensive assessment approaches [17].

Key Research Gaps and Methodological Challenges

Substantial knowledge gaps persist in understanding the relative contribution of different exposure routes to total EDC body burden. Complex mixture effects remain poorly understood, as most toxicological studies focus on single chemicals despite real-world exposure involving simultaneous contact with multiple compounds through multiple routes [14]. The "cocktail effect" of EDC mixtures may produce synergistic or additive effects that are not predictable from single-chemical studies.

Non-monotonic dose responses (NMDRs) present another significant challenge, particularly for EDCs that can produce more pronounced effects at low doses than at high doses [9]. This phenomenon complicates the establishment of threshold values and safe exposure limits. Additionally, critical windows of susceptibility—such as fetal development, infancy, and puberty—may exhibit enhanced sensitivity to EDCs, but route-specific exposure data during these periods are limited [5] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Methods for EDC Exposure Assessment

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards | Deuterated BPA, carbon-13 labeled phthalates, native POP standards | Instrument calibration, isotope dilution quantification, recovery calculations | Purity verification, stability during storage, preparation of mixed stock solutions |

| Biological Matrices | Pooled human urine, serum, synthetic urine, artificial sweat | Quality control materials, method development, matrix effect studies | Homogeneity, stability, commutability with native samples |

| Sample Collection Media | Silanized glass vials, PUF plugs, quartz filters, silicone wristbands | Environmental and biological sample collection, storage, and transport | Blank levels, recovery efficiency, sample stability |

| Chromatography Columns | C18 reverse-phase, HILIC, phenyl-modified stationary phases | Separation of EDCs and metabolites from complex matrices | Column selectivity, peak shape, retention time stability |

| Mass Spectrometry | Triple quadrupole MS, high-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) instruments | Target quantification and suspect screening | Sensitivity, selectivity, dynamic range, mass accuracy |

The primary exposure triad of ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption represents fundamental pathways through which EDCs enter the human body and disrupt endocrine function. Each route involves distinct exposure sources, physiological barriers, and methodological approaches for assessment. Current evidence demonstrates that real-world exposure typically occurs through multiple routes simultaneously, resulting in cumulative body burdens that are challenging to quantify and link to specific health outcomes. Advancements in exposure science, including improved biomonitoring techniques, computational modeling, and novel sampling approaches, continue to enhance our understanding of these complex exposure pathways. Future research priorities should include development of standardized methods for aggregate exposure assessment, investigation of mixture effects across exposure routes, and elucidation of critical windows of susceptibility throughout the lifespan.

This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of three major classes of chemicals of concern—Plasticizers, Heavy Metals, and Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)—within the context of Endocrine Disrupting Chemical (EDC) exposure research. These substances represent significant environmental health challenges due to their persistence, bioavailability, and ability to interfere with hormonal systems through multiple exposure routes including food, air, and dermal absorption [8] [18]. Growing evidence links EDC exposure to diverse adverse health outcomes including reproductive impairment, neurodevelopmental disorders, metabolic dysfunction, and cancer, driving urgent need for comprehensive risk assessment frameworks and mitigation strategies [8].

The following sections detail the properties, exposure pathways, health impacts, and analytical methods for each chemical class, with specific emphasis on their roles as endocrine disruptors. Technical protocols and research tools are provided to support scientific investigation and drug development efforts aimed at understanding and counteracting their toxicological effects.

Plasticizers

Definition and Key Applications

Plasticizers are additive chemicals used primarily to increase the flexibility, durability, and workability of polymeric materials, especially polyvinyl chloride (PVC) [19]. They function by embedding themselves between polymer chains, reducing secondary molecular bonds and decreasing glass transition temperature, thereby making rigid materials more pliable [19]. Global plasticizer market volume is projected to grow from $17 billion in 2022 to $22.5 billion by 2027, with non-phthalate alternatives representing an increasing share (approximately 35% in 2017, expected to reach 40%) [20].

Table 1: Major Plasticizer Classes and Applications

| Chemical Class | Major Compounds | Primary Applications | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phthalates | DEHP, DINP, DIDP, DBP | PVC products, vinyl flooring, cables, medical devices [19] | Good plasticizing efficiency, low cost, durability [19] |

| Non-Phthalate Plasticizers (NPPs) | DEHT, DINCH, ATBC, ESBO | Food packaging, medical devices, children's toys, cosmetics [21] [20] | Perceived as safer alternatives; varying efficacy [21] |

| Adipates | DEHA, DINA, DiDA | Food packaging films, synthetic leather [21] | Improved low-temperature flexibility [21] |

| Trimellitates | TOTM | High-temperature wire and cable insulation [19] | High temperature resistance, lower volatility [19] |

| Citrates | ATBC | Food contact materials, medical devices, cosmetics [20] | Low toxicity, biodegradable [20] |

| Polyesters | Various | Require high permanence applications [19] | Low migration, high molecular weight [19] |

Plasticizers as Endocrine Disruptors

Substantial evidence identifies numerous plasticizers as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) that interfere with hormonal signaling pathways. Multiple epidemiological studies demonstrate consistent associations between plasticizer exposure and adverse reproductive outcomes including impaired semen quality, decreased ovarian reserve, infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and altered hormone levels [18]. The mechanisms of disruption include:

- Estrogen and Androgen Receptor Interactions: Many plasticizers mimic or block natural hormones, particularly estrogen and androgen, altering receptor activation and downstream gene expression [18].

- Steroidogenesis Interference: Plasticizers can disrupt the synthesis and metabolism of endogenous steroid hormones [21].

- Nuclear Receptor Activation: Compounds including DEHP, DINP, and DINCH can activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) which regulate lipid metabolism and adipogenesis [20].

Emerging research indicates that some non-phthalate alternatives initially marketed as safer may present similar endocrine-disrupting concerns, representing cases of "regrettable substitution" [20]. For example, alternative plasticizers such as acetyl tributyl citrate (ATBC), diisononyl cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate (DINCH), and tris-2-ethylhexyl phosphate (TEHP) show potential endocrine disrupting properties [20].

Exposure Routes and Experimental Assessment

Human exposure to plasticizers occurs through multiple pathways, with the relative contribution of each route varying by compound properties and population-specific factors:

- Food Ingestion: Primary exposure route for many plasticizers, especially through migration from food packaging and processing equipment [21]. Lipid-rich foods particularly accumulate lipophilic plasticizers.

- Dermal Absorption: Direct contact with personal care products, cosmetics, and vinyl materials containing plasticizers [21].

- Inhalation: Indoor air and dust containing volatilized or particulate-bound plasticizers, especially in environments with PVC flooring or furnishings [20].

- Parenteral Exposure: Direct introduction into bloodstream via medical devices such as PVC intravenous tubing and blood bags [19].

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Plasticizer Assessment

| Matrix | Sample Preparation | Analytical Technique | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | Enzymatic deconjugation, solid-phase extraction, dilution [18] | LC-MS/MS | Secondary metabolites (e.g., monoesters for phthalates, oxidative metabolites for DINCH) |

| Dust | Accelerated solvent extraction, gel permeation chromatography cleanup [20] | GC-MS | Multiple plasticizer concentrations; source attribution |

| Food Simulants | Solvent extraction, membrane filtration | HPLC-UV/FLD | Migration rates under standardized conditions |

| Serum | Protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction | HPLC-MS/MS | Parent compounds and biomarkers of effect |

| Indoor Air | Active sampling (sorbent tubes), passive air samplers | GC-MS | Gas-phase and particle-phase concentrations |

Experimental Protocol: Biomonitoring of Plasticizer Metabolites

- Sample Collection: Collect spot or first-morning void urine samples in pre-cleaned polypropylene containers; store at -80°C until analysis.

- Sample Preparation: Thaw samples overnight at 4°C. Mix by vortexing. Aliquot 1 mL urine into reaction vials. Add internal standard mixture (deuterated analogs).

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Adjust pH to 6.5 with ammonium acetate buffer. Add β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase preparation. Incubate at 37°C for 90 minutes.

- Solid-Phase Extraction: Load hydrolysate onto preconditioned Oasis HLB cartridges. Wash with 5% methanol in water. Elute with methanol.

- Analysis: Concentrate eluent under nitrogen stream. Reconstitute in mobile phase. Analyze by LC-MS/MS using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

- Quality Control: Include method blanks, quality control pools, and standard reference materials with each batch [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plasticizer Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., D4-DEHP, 13C-BPA) | Quantification correction for recovery and matrix effects | LC-MS/MS biomonitoring |

| β-Glucuronidase/Arylsulfatase (Helix pomatia) | Enzymatic deconjugation of phase II metabolites | Urine sample preparation prior to extraction |

| Oasis HLB Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Extraction and cleanup of analytes from biological matrices | Sample preparation for urine, serum |

| C18 Reverse Phase Chromatography Columns | Separation of analytes by hydrophobicity | LC-MS/MS analysis |

| Certified Reference Materials (NIST SRM 3672, 3673) | Method validation and quality assurance | Organic contaminants in dust and soils |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Selective extraction of target analytes | Sample clean-up for complex matrices |

| Recombinant Nuclear Receptor Assays (ERα, AR, PPARγ) | Assessment of endocrine disruption potential | High-throughput screening of plasticizers |

Heavy Metals

Environmental Presence and Health Risks

Heavy metals represent a significant class of inorganic contaminants with well-established endocrine disrupting properties. Agricultural soil contamination has become increasingly severe due to urbanization and industrialization, with heavy metals permeating soil ecosystems through atmospheric deposition, surface runoff, and subsurface migration [22]. These elements pose significant ecological risks due to their environmental persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and toxicity [22].

Table 4: Heavy Metals of Concern: Sources and Health Effects

| Heavy Metal | Major Anthropogenic Sources | Primary Health Effects | Endocrine Disruption Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | Pesticide residues, industrial waste, mining [22] | Skin lesions, cardiovascular disease, cancer [23] | Glucocorticoid receptor disruption, steroidogenesis interference [8] |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Phosphate fertilizers, battery manufacturing, metal plating [22] | Renal dysfunction, osteoporosis, cancer [22] | Estrogen receptor activation, progesterone receptor suppression |

| Lead (Pb) | Leaded gasoline, paints, electronic waste, mining [23] | Neurodevelopmental deficits, anemia, hypertension [23] | Hypothalamic-pituitary axis disruption, growth hormone alteration |

| Chromium (Cr) | Tanneries, textile manufacturing, metal plating [23] | Allergic dermatitis, lung cancer, renal damage [23] | Oxidative stress, hormone receptor modification |

| Nickel (Ni) | Metal alloy production, combustion of fossil fuels [23] | Contact dermatitis, lung fibrosis, nasal cancer [23] | Hypoxia signaling pathway activation |

| Mercury (Hg) | Coal combustion, gold mining, dental amalgams [8] | Neurological impairment, renal damage, developmental toxicity [8] | Thyroid hormone disruption, estrogenic effects |

Exposure Assessment and Risk Quantification

Heavy metal exposure occurs through ingestion of contaminated food and water, inhalation of particulate matter, and dermal contact with contaminated media [23]. Advanced risk assessment approaches integrate multiple exposure pathways using probabilistic methods:

Table 5: Health Risk Assessment Indices for Heavy Metals

| Assessment Index | Calculation Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Geo-accumulation Index (Igeo) | Igeo = log₂(Cn/1.5Bn) where Cn is measured concentration, Bn is background concentration [22] | Igeo ≤ 0: unpolluted; Igeo > 5: extremely polluted |

| Contamination Factor (CF) | CF = Cmetal/Cbackground | CF < 1: low contamination; CF ≥ 6: very high contamination |

| Pollution Load Index (PLI) | PLI = (CF1 × CF2 × ... × CFn)^1/n | PLI > 1 indicates deterioration of site quality |

| Hazard Quotient (HQ) | HQ = CDI/RfD where CDI is chronic daily intake, RfD is reference dose [23] | HQ < 1: unlikely adverse effects; HQ ≥ 1: potential adverse effects |

| Hazard Index (HI) | HI = ΣHQingestion + ΣHQinhalation + ΣHQdermal [23] | HI < 1: safe level; HI ≥ 1: potential non-carcinogenic risk |

| Carcinogenic Risk (CR) | CR = CDI × SF where SF is slope factor | CR < 10⁻⁶: negligible risk; CR > 10⁻⁴: unacceptable risk |

Experimental Protocol: Soil Heavy Metal Analysis and Risk Assessment

- Sample Collection: Collect surface (0-20 cm) and deep (150-200 cm) soil samples using stainless steel tools at predetermined grid points. Record GPS coordinates.

- Sample Preparation: Air-dry samples at room temperature, remove visible gravel and plant roots. Grind and homogenize using agate mortar, sieve through 2-mm nylon mesh.

- Acid Digestion: Weigh 0.5 g soil sample into Teflon digestion vessel. Add 9 mL HNO₃, 3 mL HCl, and 2 mL HF. Digest using microwave-assisted system with temperature ramp to 180°C maintained for 15 minutes.

- Analysis: Cool digested samples, transfer to volumetric flasks, dilute to 50 mL with deionized water. Analyze using ICP-OES with appropriate quality controls (blanks, duplicates, certified reference materials BCR-667).

- Spatial Analysis: Input georeferenced concentration data into GIS software (QGIS). Apply inverse distance weighting (IDW) interpolation to create contamination distribution maps.

- Risk Calculation: Apply Monte Carlo simulation (10,000 iterations) to account for parameter uncertainty in exposure factors. Calculate Hazard Quotients (HQ) and Hazard Index (HI) for different age groups via oral ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact pathways [22] [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 6: Essential Research Reagents for Heavy Metal Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃, HCl, HF) | Sample digestion and dissolution | Microwave-assisted acid digestion of environmental samples |

| Certified Reference Materials (NIST SRM 2709, 2710, BCR-667) | Quality assurance and method validation | Analytical accuracy verification for soil/sediment analysis |

| ICP-MS/MS Tuning Solutions | Instrument calibration and optimization | Sensitivity and oxide/carbon interference minimization |

| Single-Element Stock Standards (1000 mg/L) | Calibration curve preparation | Quantitative analysis by ICP-OES/ICP-MS |

| Chelating Resins (Chelex-100, IMAC) | Preconcentration and matrix separation | Trace metal analysis in environmental waters |

| Modified DGT (Diffusive Gradients in Thin Films) | In-situ measurement of bioavailable metals | Passive sampling in waters and sediments |

| CRMs for Biological Monitoring (Seruon, Blood, Urine) | Quality control for biomonitoring | Human exposure assessment |

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)

Definition and Regulatory Framework

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) are toxic chemical compounds that resist natural degradation processes, persist in the environment for extended periods, bioaccumulate in living organisms, and biomagnify through food chains [24] [25]. The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, adopted in 2001, is a global treaty to protect human health and the environment from POPs, with over 180 participating countries committing to control and reduce these substances [24] [25].

POPs include intentionally produced chemicals such as industrial compounds and pesticides, as well as unintentional byproducts formed during combustion and industrial processes [24]. Key characteristics include:

- Persistence: Resistance to photolytic, chemical, and biological degradation (half-lives exceeding 6 months)

- Bioaccumulation: Bioconcentration factors > 5,000 in aquatic species

- Long-Range Transport: Capable of traveling thousands of kilometers from emission sources

- Toxicity: Adverse effects on human health and wildlife at low concentrations

The "Dirty Dozen" and Beyond

The original "Dirty Dozen" POPs identified by the Stockholm Convention include [24]:

Table 7: Initial POPs Listed under Stockholm Convention

| POP Category | Specific Compounds | Historical Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Pesticides | Aldrin, Chlordane, DDT, Dieldrin, Endrin, Heptachlor, Mirex, Toxaphene | Agricultural pest control, vector management |

| Industrial Chemicals | Hexachlorobenzene, Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) | Electrical equipment, solvents, fungicides |

| Byproducts | Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (dioxins), Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (furans) | Combustion processes, chemical manufacturing |

While many legacy POPs are now banned or restricted in most countries, their persistence ensures continued environmental presence and health impacts. DDT, for example, remains in limited use for malaria control in some regions despite widespread bans, highlighting the challenge of balancing public health benefits against environmental contamination [24].

Endocrine Disruption Mechanisms

POPs exert endocrine disrupting effects through multiple mechanisms that interfere with hormonal signaling pathways:

- Receptor-Mediated Effects: Many POPs interact directly with nuclear hormone receptors, particularly estrogen receptors (ER), androgen receptors (AR), thyroid hormone receptors (TR), and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) [25] [18].

- Hormone Synthesis Alteration: POPs can interfere with steroidogenic enzymes including cytochrome P450 complexes, altering the synthesis and metabolism of endogenous hormones [8].

- Hormone Transport Disruption: Some POPs compete with thyroid hormones for binding to transport proteins such as transthyretin, affecting hormone distribution and bioavailability [18].

- Cellular Signaling Interference: POPs can disrupt post-receptor signaling pathways including calcium signaling and protein kinase cascades [8].

Experimental Protocol: POPs Analysis in Biological Samples

- Sample Collection and Storage: Collect adipose tissue, serum, or breast milk in pre-cleaned glass containers. Store at -20°C or lower to prevent degradation.

- Lipid Extraction: Homogenize sample with anhydrous sodium sulfate. Extract lipids using accelerated solvent extraction (ASE) with dichloromethane:hexane (1:1, v/v) at 100°C and 1500 psi.

- Lipid Removal and Cleanup: Determine lipid content gravimetrically. Remove lipids using gel permeation chromatography (GPC) or sulfuric acid treatment.

- Fractionation: Separate compound classes using silica gel column chromatography with sequential elution using hexane, hexane:dichloromethane, and dichloromethane:methanol.

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze fractions using gas chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry (GC-HRMS) with electron impact ionization.

- Quality Assurance: Include procedural blanks, matrix spikes, and certified reference materials (NIST SRM 1957, 1947) with each batch. Use isotope dilution quantification with 13C-labeled internal standards [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 8: Essential Research Reagents for POPs Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 13C/2H-Labeled Internal Standards | Quantification correction and recovery monitoring | Isotope dilution mass spectrometry |

| Silica Gel, Alumina, Florisil | Adsorbents for chromatographic cleanup | Sample preparation and fractionation |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Lipid removal from biological extracts | Sample cleanup prior to GC analysis |

| HRGC-HRMS Systems | High-resolution separation and detection | Congener-specific POPs analysis |

| CALUX Bioassay Kits (Chemically Activated LUciferase eXpression) | Bioanalytical screening for dioxin-like activity | High-throughput toxicity screening |

| Certified Reference Materials (NIST, WMF, BCR) | Method validation and quality control | Analytical accuracy verification |

| Passive Air Samplers (PUF disks, XAD resins) | Monitoring atmospheric POPs | Long-term spatial and temporal trend studies |

Plasticizers, heavy metals, and persistent organic pollutants represent three distinct but interconnected classes of endocrine disrupting chemicals with significant implications for human and environmental health. Despite differing in chemical structure and applications, they share common features including environmental persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and the ability to disrupt hormonal systems at low exposure levels.

Research gaps remain in understanding the full scope of health impacts, particularly from chronic low-dose exposures and complex mixtures. The phenomenon of "regrettable substitution"—replacing regulated chemicals with structurally similar alternatives that may pose comparable risks—highlights the need for more comprehensive chemical safety assessment frameworks [21] [20]. Advanced analytical techniques, biomonitoring programs, and computational toxicology approaches will be essential for identifying emerging concerns and developing effective risk management strategies.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to assess cumulative effects, elucidate mechanisms of action across different life stages, and identify susceptible populations. Integration of novel approach methodologies including high-throughput screening, organ-on-a-chip systems, and adverse outcome pathways will accelerate the identification of hazardous properties and support evidence-based decision making for chemical regulation and public health protection.

Environmental endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a diverse class of synthetic and naturally occurring compounds that interfere with the normal function of the endocrine system. The molecular mechanisms through which these chemicals exert their effects are complex and multifaceted, primarily involving receptor interference, oxidative stress induction, and epigenetic modifications [14] [26]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for assessing the full scope of health risks posed by EDCs, which enter the human body through food, air, and skin absorption [14] [27].

Research demonstrates that EDCs disrupt hormonal homeostasis through direct and indirect pathways, leading to adverse health outcomes including reproductive dysfunction, metabolic disorders, neurodevelopmental issues, and hormone-sensitive cancers [28] [26]. This technical review examines the core molecular mechanisms of EDC action, provides quantitative data on exposure thresholds and effects, outlines experimental methodologies for mechanistic studies, and visualizes key signaling pathways disrupted by these ubiquitous environmental contaminants.

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

Receptor Interference

EDCs primarily disrupt endocrine function by directly interfering with hormone receptor signaling pathways. These chemicals can mimic natural hormones, antagonize their actions, or alter receptor expression and function [14] [29].

Nuclear Receptor Interactions: Many EDCs exert their effects through binding to nuclear hormone receptors, particularly estrogen receptors (ERs), androgen receptors (ARs), progesterone receptors, thyroid receptors, and retinoid receptors [29] [26]. Bisphenol A (BPA) demonstrates high-affinity binding to estrogen receptors, fundamentally altering hormonal balance at typical daily intake levels of 0.1-4 µg/kg body weight [14] [27]. Phthalates, particularly di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), interfere with androgen receptor signaling and are routinely detected in seminal plasma at concentrations of 0.77-1.85 μg/mL, with documented associations to reduced sperm concentration and motility [14] [27].

Non-Monotonic Dose Responses: EDCs frequently exhibit non-monotonic dose-response (NMDR) relationships, where low-dose chronic exposure may produce more pronounced biological effects than acute high-dose exposure [14] [30]. Computational modeling suggests that interference with systemic negative feedback regulation in endocrine axes serves as a potential mechanism for these counterintuitive dose-response patterns [30]. The NMDR phenomenon complicates traditional toxicological risk assessment, which typically assumes monotonic dose-response relationships.

Table 1: Receptor-Mediated Mechanisms of Select EDCs

| EDC Category | Specific Compounds | Primary Receptors Targeted | Affinity/EC50 | Cellular Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasticizers | Bisphenol A (BPA) | ERα, ERβ, GPR30 | High affinity for ERβ [27] | Altered estrogen signaling, cell proliferation |

| Phthalates | DEHP, DBP, DEP | Androgen Receptor, PPARγ | Seminal concentrations: 0.77-1.85 μg/mL [27] | Reduced sperm quality, testosterone suppression |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants | PCBs, Dioxins | Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor, ER | Toxic equivalence factors: 0.0001-1 [14] | Disrupted steroidogenesis, oxidative stress |

| Heavy Metals | Cadmium, Lead | Estrogen Receptor, Glucocorticoid Receptor | Blood lead >10 μg/dL causes sperm DNA damage [14] | Receptor activation, hormone mimicry |

Oxidative Stress Induction

Oxidative stress represents a central mechanism in EDC toxicity, occurring when the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) overwhelms cellular antioxidant defenses [14] [31].

Reactive Oxygen Species Generation: Multiple EDCs induce excessive ROS production through various pathways. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles trigger ROS generation resulting in sperm membrane damage with an ED50 of 150 mg/kg [14]. Heavy metals including cadmium and lead promote oxidative stress through Fenton chemistry and depletion of glutathione, a key cellular antioxidant [14]. Phthalates like DEHP undergo metabolic activation to generate free radicals that oxidize cellular macromolecules [32].

Cellular Consequences: Oxidative damage from EDCs affects lipids, proteins, and DNA, leading to membrane disruption, enzyme inactivation, and mitochondrial dysfunction [14] [31]. In the cardiovascular system, EDCs have been shown to promote atherosclerosis through ROS-mediated endothelial dysfunction, impaired nitric oxide production, and oxidative modification of LDL cholesterol [31]. In male reproduction, oxidative stress damages sperm membrane integrity and DNA, compromising fertilizing potential and embryo development [14].

Mediating Role in Disease Processes: Recent evidence identifies oxidative stress as a critical mediator linking EDC exposure to various disease outcomes. A 2025 cross-sectional study demonstrated that oxidative stress biomarkers (bilirubin and iron) mediated the relationship between EDC mixtures and phenotypic aging acceleration, with mediation proportions of -24.86% and -21.06%, respectively [33].

Table 2: Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in EDC Research

| Biomarker Category | Specific Markers | Detection Methods | Significance in EDC Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Peroxidation | MDA, 4-HNE, 8-iso-PGF2α | HPLC, ELISA, GC-MS | Indicates membrane damage, atherosclerosis risk [31] |

| DNA Oxidation | 8-OHdG, Oxoguanine glycosylase | LC-MS, Immunoassays | Genotoxic effects, cancer risk assessment |

| Protein Carbonyls | Carbonylated proteins | DNPH assay, Western blot | Cellular dysfunction, enzyme inactivation |

| Antioxidant Enzymes | SOD, Catalase, GPx | Activity assays, ELISA | Compensatory response, oxidative burden |

| Non-enzymatic Antioxidants | Glutathione, Bilirubin | Colorimetric assays, HPLC | Mediating role in EDC-aging relationship [33] |

Epigenetic Modifications

Epigenetic mechanisms represent a crucial pathway through which EDCs exert long-lasting health effects, including transgenerational inheritance of disease susceptibility [14] [32].

DNA Methylation Changes: EDC exposure induces alterations in DNA methylation patterns, particularly at imprinted genes and regulatory elements of hormone-responsive genes [32]. Phthalate exposure has been associated with hypomethylation of the H19 locus, an imprinted gene involved in growth regulation [26]. These changes can persist long after exposure cessation and may be transmitted to subsequent generations, as demonstrated in animal studies [14] [32].

Histone Modifications: EDCs alter post-translational modifications of histone proteins, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination [32] [26]. These modifications change chromatin accessibility and gene expression patterns without altering the underlying DNA sequence. For example, paternal exposure to EDCs has been linked to histone modifications in sperm that may influence offspring health outcomes [26].

Noncoding RNA Expression: MicroRNAs and other noncoding RNAs are differentially expressed following EDC exposure and contribute to their toxic effects by regulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level [32]. Phthalates have been shown to induce organ-specific changes in miRNA expression profiles, potentially contributing to disease pathogenesis in hormone-sensitive tissues [32].

Table 3: Epigenetic Alterations Induced by EDCs

| Epigenetic Mechanism | EDCs with Documented Effects | Specific Genes/Regions Altered | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | Phthalates, BPA, PCBs | H19 locus hypomethylation [26] | Growth dysregulation, infertility |

| Histone Modification | BPA, Phthalates | Histone acetylation/methylation changes [26] | Altered chromatin structure, gene expression |

| Noncoding RNA | DEHP, BPA, Heavy Metals | miRNA expression profiles [32] | Organ-specific toxicity, disease risk |

| Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance | Vinclozolin, Phthalates | Sperm epigenome alterations [32] | Multi-generational reproductive effects |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Receptor Binding Assays

Competitive Binding Studies: Experimental protocols for assessing EDC receptor interactions typically employ competitive binding assays using tritiated or fluorescently-labeled natural ligands. Cell-free systems expressing purified hormone receptors are incubated with radiolabeled reference ligands (e.g., [3H]-estradiol for ER binding) in the presence of increasing concentrations of EDCs. Non-specific binding is determined by parallel incubations with a large excess of unlabeled ligand. Following incubation, bound and free ligands are separated by charcoal-dextran adsorption, filtration, or size-exclusion chromatography, and radioactivity or fluorescence is quantified [29].

Transcriptional Activation Assays: Reporter gene assays in cell culture models provide functional assessment of EDC effects on receptor signaling. Cells are transfected with expression vectors for specific nuclear receptors and corresponding reporter constructs containing receptor-responsive elements upstream of luciferase or other easily quantifiable genes. After exposure to EDCs, reporter activity is measured to determine whether the test compound acts as an agonist, antagonist, or mixed function modulator [29].

Structural Studies: X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy reveal atomic-level interactions between EDCs and hormone receptors, identifying key binding pocket residues and conformational changes that underlie receptor activation or inhibition [29].

Oxidative Stress Assessment

ROS Detection Methods: Intracellular ROS generation following EDC exposure is typically quantified using fluorescent probes such as 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), dihydroethidium (DHE) for superoxide, and MitoSOX Red for mitochondrial superoxide. Flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy, and microplate readers are used for detection and quantification [33] [31].

Biomarker Analysis: Oxidative damage biomarkers are measured using various techniques. Lipid peroxidation products (MDA, 4-HNE) are quantified by HPLC with fluorescence detection or ELISA. DNA oxidation marker 8-OHdG is measured by LC-MS/MS or immunoassays. Protein carbonyl content is determined by derivatization with dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) followed by spectrophotometric detection or Western blotting [33] [31].

Antioxidant Capacity Assays: Cellular antioxidant status is evaluated by measuring antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, catalase, GPx) through spectrophotometric methods and quantifying non-enzymatic antioxidants (glutathione, bilirubin) using colorimetric, fluorometric, or HPLC-based approaches [33].

Epigenetic Analysis

DNA Methylation Profiling: Genome-wide DNA methylation patterns are assessed using bisulfite conversion-based methods followed by sequencing (Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing, Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing) or array-based platforms (Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip). Locus-specific methylation is analyzed by bisulfite pyrosequencing or methylation-specific PCR [32].

Histone Modification Analysis: Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays using antibodies specific to modified histones (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K4me3) followed by qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) or sequencing (ChIP-seq) enable genome-wide mapping of histone modifications. Western blotting with modification-specific antibodies provides global assessment of histone mark levels [32].

Noncoding RNA Expression Profiling: Next-generation sequencing of small RNA libraries identifies differential expression of miRNAs and other noncoding RNAs following EDC exposure. RT-qPCR with stem-loop primers enables validation and quantification of specific miRNAs of interest [32].

Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated Molecular Mechanisms of EDC Action. This pathway illustrates how EDC exposure through various routes triggers three primary molecular mechanisms that converge to produce adverse health outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for EDC Mechanism Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Plasmids | ER/AR-responsive luciferase constructs | Receptor activation profiling | Vector backbone affects sensitivity; include controls for cytotoxicity |

| ROS Detection Probes | DCFH-DA, MitoSOX Red, DHE | Oxidative stress measurement | Select appropriate probe for specific ROS; consider compartmentalization |

| Epigenetic Inhibitors | 5-azacytidine (DNMT inhibitor), TSA (HDAC inhibitor) | Mechanistic studies of epigenetic modifications | Determine optimal concentration and duration to avoid off-target effects |

| Receptor Antibodies | Anti-ERα, Anti-AR, Anti-PPARγ | Western blot, IHC, ChIP | Validate specificity using knockout controls or siRNA |

| Metabolic Enzymes | CYP450 isoforms, UGT enzymes | Metabolism and bioactivation studies | Use human recombinant enzymes for human health risk assessment |

| Hormone Assays | ELISA/RIA for testosterone, estradiol, TSH | Endpoint analysis in exposed models | Consider cross-reactivity with EDCs in immunoassays |

| Epigenetic Kits | Methylation-specific PCR, ChIP, miRNA isolation | Epigenetic modification analysis | Include bisulfite conversion controls; optimize shearing for ChIP |

The molecular mechanisms of endocrine disruption involve complex, interconnected pathways that span from initial receptor interactions to lasting epigenetic reprogramming. Receptor interference represents the most direct pathway, with EDCs mimicking or blocking endogenous hormones at nuclear receptors critical for development, metabolism, and reproduction [14] [29]. Oxidative stress serves as both a primary mechanism and an amplifier of EDC toxicity, damaging cellular components and activating stress-responsive signaling pathways [33] [31]. Epigenetic modifications provide a plausible explanation for long-term and transgenerational health effects, with EDCs inducing stable changes in gene expression patterns that persist beyond the exposure period [14] [32].

Future research directions should prioritize understanding mixture effects, as real-world exposure invariably involves multiple EDCs simultaneously [14]. Additionally, elucidating the precise mechanisms underlying non-monotonic dose responses will enhance risk assessment accuracy [30]. The development of epigenetic biomarkers for early detection of EDC exposure and affected pathways holds promise for preventive interventions [34] [32]. Integrating multi-omics approaches with advanced bioinformatics will further unravel the complex interplay between EDC exposure, molecular mechanisms, and disease pathogenesis, ultimately informing evidence-based regulatory policies and protective strategies.

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) paradigm establishes that environmental exposures during critical developmental windows exert profound influences on long-term health trajectories [35]. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) represent a significant class of environmental stressors capable of crossing the placental barrier and accumulating in fetal tissues, with exposure timing and dosage determining specific physiological outcomes [35]. Emerging evidence indicates that prenatal EDC exposure can reprogram physiological systems through epigenetic mechanisms, potentially creating transgenerational effects that manifest as metabolic disorders, reproductive dysfunction, impaired neurodevelopment, and immune dysregulation later in life [35] [36]. This technical review synthesizes current evidence on life-stage vulnerability to EDCs, detailing specific exposure routes—including dietary, airborne, and dermal pathways—and providing methodological guidance for researchers investigating these critical exposure windows.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals comprise a diverse group of exogenous substances that interfere with hormone action, synthesis, metabolism, or signaling pathways [1] [37]. These chemicals can mimic, block, or otherwise disrupt the normal function of hormonal systems, particularly during sensitive developmental periods when organizational effects are permanent [35]. The concept of "critical windows of exposure" posits that specific developmental stages—such as prenatal development, early infancy, puberty, and pregnancy—exhibit heightened susceptibility to EDC effects due to rapid cellular differentiation, tissue formation, and metabolic programming [35].

According to the DOHaD framework, environmental stressors encountered during these plastic developmental periods can permanently alter an individual's physiological set points, increasing disease susceptibility across their lifespan [35] [38]. The fetus is particularly vulnerable to EDCs due to immature metabolic capabilities, rapidly developing organ systems, and the absence of fully functional blood-brain and other protective barriers [35]. Numerous EDCs, including bisphenols, phthalates, perfluorinated compounds, and persistent organic pollutants, readily cross the placental barrier, creating a direct exposure pathway to the developing fetus [35] [37].

Dietary Exposure Pathways

Diet represents the most significant exposure route for many EDCs, with chemical migration occurring from food packaging, processing equipment, and environmental contamination [35] [39].

- Food Packaging Materials: Bisphenols (BPA, BPS, BPF) leach from polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resin linings of canned foods and beverages, particularly under heat or acidic conditions [35] [37]. Phthalates migrate from flexible PVC food packaging, especially into fatty foods like meats, dairy products, and oils [35]. Recent analytical studies detected at least one EDC in 144 of 162 screened beverage products, with canned beverages showing significantly higher BPA levels compared to glass or plastic packaging [39].

- Environmental Contaminants: Persistent organic pollutants (POPs), including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxins, bioaccumulate up the food chain, concentrating in animal fats, fish, and dairy products [35]. Perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) contaminate water sources and migrate from food contact wrappers into food products [37].

- Pesticide Residues: Organophosphate and organochlorine pesticides persist on conventionally grown fruits, vegetables, and grains despite regulatory restrictions in many countries [35].

Non-Dietary Exposure Pathways

- Personal Care Products: Phthalates, parabens, and UV filters in cosmetics, lotions, fragrances, and other personal care items enable dermal absorption and inhalation exposure [1]. The frequency of product use correlates with internal body burden, with certain populations using multiple products daily [1].

- Indoor Air and Dust: Phthalates and brominated flame retardants leach from electronics, furniture, and building materials, partitioning into household dust and enabling inhalation exposure, particularly for children with hand-to-mouth behaviors [37].

- Environmental Justice Considerations: Research following Hurricane Harvey demonstrated that racial/ethnic minorities and communities with lower socioeconomic status experience disproportionately high EDC exposures due to residential proximity to industrial facilities and inadequate infrastructure [40].

Table 1: Primary EDC Classes, Exposure Routes, and Health Concerns

| EDC Class | Major Sources | Primary Exposure Routes | Key Health Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|